Individual Courses

Chapter 3 – Faculty-Library Collaboration in a Course Without Assigned Textbooks

Lauri DeRuiter-Willems and Stacey Knight-Davis

Lauri DeRuiter-Willems and Stacey Knight-Davis (both from Eastern Illinois University) (bios)

Introduction

When making textbook decisions for college courses there are many issues to consider and questions to ask. First, does the course need a textbook? Is the course focused on standard content or on applying content to ill-structured problems or projects? If the course does need a textbook, what will be the purpose of the book? Will it serve as supplemental instruction or the primary source of content? Is the textbook author also the instructor? Do students purchase textbooks, or rent them?

The primary question when deciding which, if any, textbook to adopt is this: What value does the textbook add to the course?

The primary question when deciding which, if any, textbook to adopt is this: What value does the textbook add to the course? For the two courses discussed here, a textbook was less valuable than a carefully curated selection of articles and other professional sources. Our discussion has a heavy emphasis on health promotion, because that’s our field, but we also try to generalize our thoughts so the decision process can be used in other disciplines. The decision not to use a textbook for these two courses at Eastern Illinois University (EIU) has allowed us to follow the guidelines of the course proposals while modifying the content resources to reflect current practices in the field.

Marketing Concepts for Health Promotion Professionals

Developed over the last ten years, the curriculum of Marketing Concepts for Health Promotion Professionals (DeRuiter-Willems, 2017a) addresses skills identified by interns and recent graduates as being important to have practiced and trained to use on the job. These topics were identified in several ways: by the Health Promotion department chair, who holds “exit” interviews with soon-to-be graduates (those who have completed all coursework and internship requirements), by faculty conversations with graduates through social media, by discussions with colleagues in the field, and by occasional advisory group activities.

To explore health promotion and health marketing, the course uses content in online training modules, videos and e-textbooks available through the library, and industry websites and professional organizations. After course content has been examined with the students, application of concepts happens through group and/or individual projects that follow a basic instructional plan from one semester to the next, but with a new topic or focus. The projects occur in a controlled setting in which the instructor leads the projects and offers comprehensive research support.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2017b) offers a health literacy online training program that includes several modules and videos, and a training series offered by the University of Minnesota provides supplemental information on health literacy which is added to the library module (University of Minnesota, 2017). Students study this online program, then discuss and practice the concepts during class sessions. The CDC has also created a series of social-marketing training modules (CDC, 2016). Works from the CDC and from other United States government entities are typically not covered by copyright and can be freely distributed (USAGov, 2017). Students study these modules, then review and discuss the concepts in class. The material is included in an exam.

After completing the health literacy training, students begin the health literacy project. Using a popular media news story on a current health trend or recent study, the student groups apply health literacy concepts by designing a marketing-style artifact for a specific audience to increase awareness of the health issue and offer suggestions for behavior modification. Chosen each semester based on current news, topics are ones that students are likely to use during internships and on the job. Examples include concussions, disaster preparedness, distracted driving, hydration/dehydration, the obesity epidemic as related to screen time and physical activity, infectious disease prevention/handwashing, sleep, and stress. Because these topics are important for many groups of people, they lend themselves well to this type of project.

To emphasize the health literacy concepts, each group is assigned the same topic but a unique audience. Audiences for a project addressing sleep, for example, included college students, families with young children, parents of middle school/high school students, middle/high school students themselves, and older adults with no children at home. While we do make some assumptions about audience characteristics, such as education, cognitive ability, and socioeconomic status, the purpose is for the class to see examples of artifacts that incorporate health literacy strategies and convey information to a variety of audiences. The project requires that students have a good understanding both of the topic itself and of the characteristics of a specific group of people–knowledge acquired by researching the topic through the learning management system (LMS) library module and internet searches.

It should be noted that these projects are not used in public settings with “live audiences.” The projects ultimately allow students to see several examples of products related to the same topic but tailored to and meeting the needs of different audiences. The number of audiences is determined by the number of students enrolled in the course, with the goal of having small groups of 4–5 students.

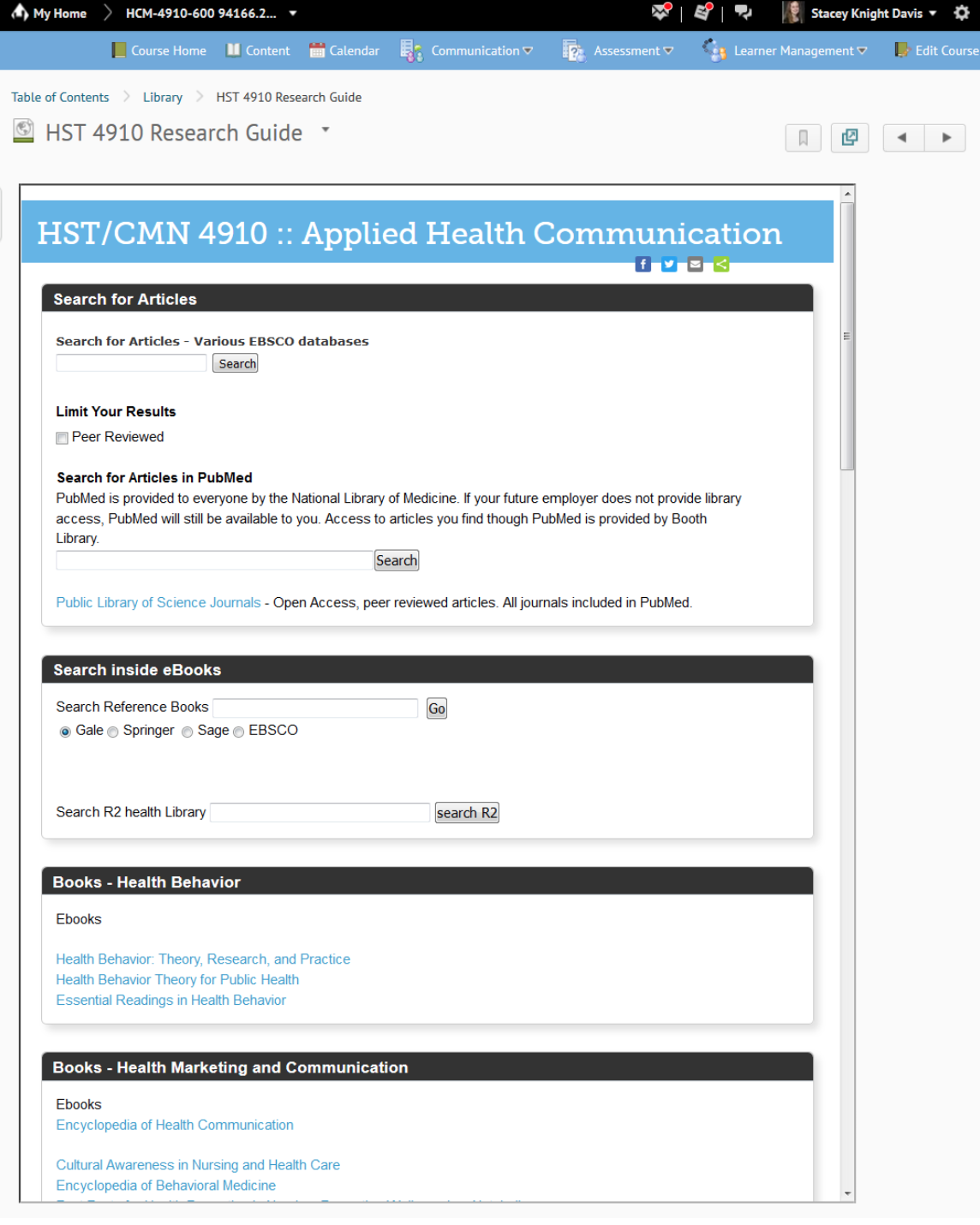

In recent years we have added the newer concept of social media marketing to the course. We bring in a guest speaker who serves as the social media director for the university, and use videos identified by the instructor and librarian as current and on-trend. After class sessions to review concepts, each student begins a blog project that allows them to research a health topic and write several related blog-style posts. The audience is assumed to be college students—more specifically, their student classmates. While a more relaxed, conversational style of writing is allowed and encouraged, each blog entry must include at least one professional/academic reference to add credibility, accuracy, reliability, and support. While these references may be found from a Google search, the library resource module also provides great direction (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Library Module for HST 2700. From HST 2700 Marketing Concepts for Health Promotion Professionals.

Reprinted with permission.

To encourage interaction, student writers are required to ask questions of their peers related to the health topic. In addition to health literacy principles, blog entries must include social media marketing and social marketing components. “The 4 C’s” (Content, Connections, Conversations, Channel), for example, are emphasized in social media marketing, and a key concept in social marketing is to encourage voluntary behavior change. Blog entries should therefore include the 4 C’s and a call to action that encourages voluntary behavior change related to the health topic.

This assignment is also kept “in-house.” To ensure a variety of topics, only one student is permitted to use each topic. The students choose topics based on a list generated from CDC Disease and Conditions web page and the CDC Healthy Living web page (CDC, 2017a, CDC 2017c).

As a culminating project, small groups are given instructions to create a marketing plan proposal. This proposal must include all of the major concepts covered during the course, including health literacy, social marketing, social media marketing, the writing of behavioral goals and objectives, and program plan components: health issue/problem description, audience/behavior analysis, and implementation/intervention strategy. Groups choose the health topic and audience, and design the implementation plan.

Applied Health Communication

Another course that does not require a textbook is Applied Health Communication (DeRuiter-Willems, 2017b), an upper division course modified after having been taught for several years. The course originally included communication content as well as student-led health communication projects, but we determined that two separate courses would better serve the students. The first course, Communication for Health Professionals, retained the textbook, and became more content-oriented, allowing for in-depth exploration of many aspects of health-related communication. The second course, Applied Health Communication, was developed to allow students to apply knowledge gained in the first course, and includes ill-structured projects developed, created, and implemented by the students. It was determined that not using a textbook would allow more flexibility and the use of more current information, and would require students to lead the research, instead of following a prepared plan. While there are assigned readings from electronic reserves and links to professional organizations, the students must find topic-specific material, and are encouraged to use the LMS library module. In addition to expanding the course content, the format of Applied Health Communication allows us to offer hybrid and online versions. Using digital material eases the burden of sending textbooks to out-of-town students. In fact, in 2016, one student was deployed overseas but was still able to participate in the online course.

The field of health promotion, like many other fields, includes basic content that is used across the discipline, and students must have a working understanding of this basic material. For health promotion, the essential content areas include dimensions of health (physical, spiritual, mental/emotional, environmental); epidemiology; lifestyle behaviors and risk factors that influence good health—physical activity, nutrition, tobacco use, mental/emotional health, alcohol/ substance use and abuse, and sexual practices; program planning—educational, promotional, events, and communications; and behavior theories. To provide a refresher on this material, the LMS library module contains ebooks, online resources, image usage, and statistical resources.

Ill-Structured Assignments

Herbert A. Simon (1977) described an ill-structured problem as “a problem whose structure lacks definition in some respect” (p. 304), and explained that it is what is left over after the well-structured problems are identified. While Simon is describing how to structure a problem so that it can be solved by a computer program, the arrangement of ill-structured problems makes them excellent teaching tools that mimic situations encountered by health promotion professionals and in many other disciplines. Foshay, Silber and Stelnicki (2003) explained that an “ill-structured problem has no clear or spelled out initial state, goal, set of operations or constraints” (p. 130). Such problems reflect those typically encountered by adults in work and life situations, and addressing them results in meaningful and useful learning. Students are required not only to develop their own interpretation of a problem, but to create a solution. There may be multiple solutions appropriate to resolving the problem. Two central requirements in these assignments are that a student or group must justify the solution to show that it can be implemented and solves the problem, and must reflect on the process. As Foshay, Silber and Stelnicki (2003) concluded, “it is the reflection on the process that aids in both more effective problem solving next time, and in generalization of the process to new, related problems” (p. 131). This reflection is what we hope our students will retain and use during internships and work settings.

In Applied Health Communication, a senior-level course, the capstone project fits the criteria for an ill-structured problem. Students apply what they have learned and reviewed in the course by creating individual health communication campaigns. This assignment is similar to the marketing plan project previously described, as students pick and develop their topics, but they do this individually rather than in groups. The project is evaluated using a holistic rubric, which provides a structure and specific elements to consider in the evaluation; there is no way for the evaluation process to be mechanized. While some boundaries and requirements are built into the project, students are free to explore and create, to bring in knowledge from varied sources, and to add new information throughout the project. This capstone project demonstrates student success in integrating course content, design skills, and communication techniques.

With typical assignments having very specific guidelines and requirements, ill-structured assignments can be overwhelming to students not familiar with them.

With typical assignments having very specific guidelines and requirements, ill-structured assignments can be overwhelming to students not familiar with them. Foshay, Silber and Stelnicki (2003) and Simon (1977) suggested that an ill-structured problem can be approached by breaking it into smaller, better-structured units. Foshay, Silber and Stelnicki (2003) offered the following general teaching strategies:

- Providing an appropriate sequence of problems that fit the context in which the problem-solving skill will be applied.

- Providing instruction, examples, and practice in a sequence that allows learners to develop the problem-solving heuristics for themselves.

- Keeping cognitive load within the capabilities of the learners through problem type, format selection, and the use of scaffolding.

- Allowing for and encouraging reflection on the process. (p. 132)

For the health communication campaign, students complete a series of small projects with defined constraints. For example, students write a problem description for the topic they have chosen for their campaign, followed by an audience behavior analysis. Use of information from the course materials and library module is strongly encouraged for both assignments. To support the reflection process, students post summaries of their papers in online discussions, along with ideas for the next phase of their campaigns. Classmates ask questions and offer critiques based on their own understanding of the process. One of the key elements of an ill-structured assignment is that students can continually add information and reformulate their approach to the problem. Providing information for the student to use throughout the campaign creation project is a balancing act between offering a well-defined list of tools and resources appropriate for all projects and providing access to a wide variety of information that is not fully curated. The students are in the driver’s seat, and are expected to identify resources that meet the criteria of being credible, timely, and reputable.

Professional Organizations and Online Sources

Organizations that serve as authorities in a particular field often provide information—through websites, publications, conferences, and so on—that can be helpful to students. And professional organizations provide members with continuing education and professional development opportunities that are important for keeping current with industry trends and information. Health professionals, for example, are often members of the Society of Public Health Educators (SOPHE), the American Public Health Association (APHA), and SHAPE America—the Society of Health and Physical Educators. In additional to annual conferences, many organizations have state or regional conferences and meetings. Organization websites are often not limited to members, and can therefore be very useful as online resources for students. Many of these organizations also have a social media presence that promotes membership and provides educational information to the general public. We have included these organizations and websites in the course library module.

Supplying Information Resources to Students

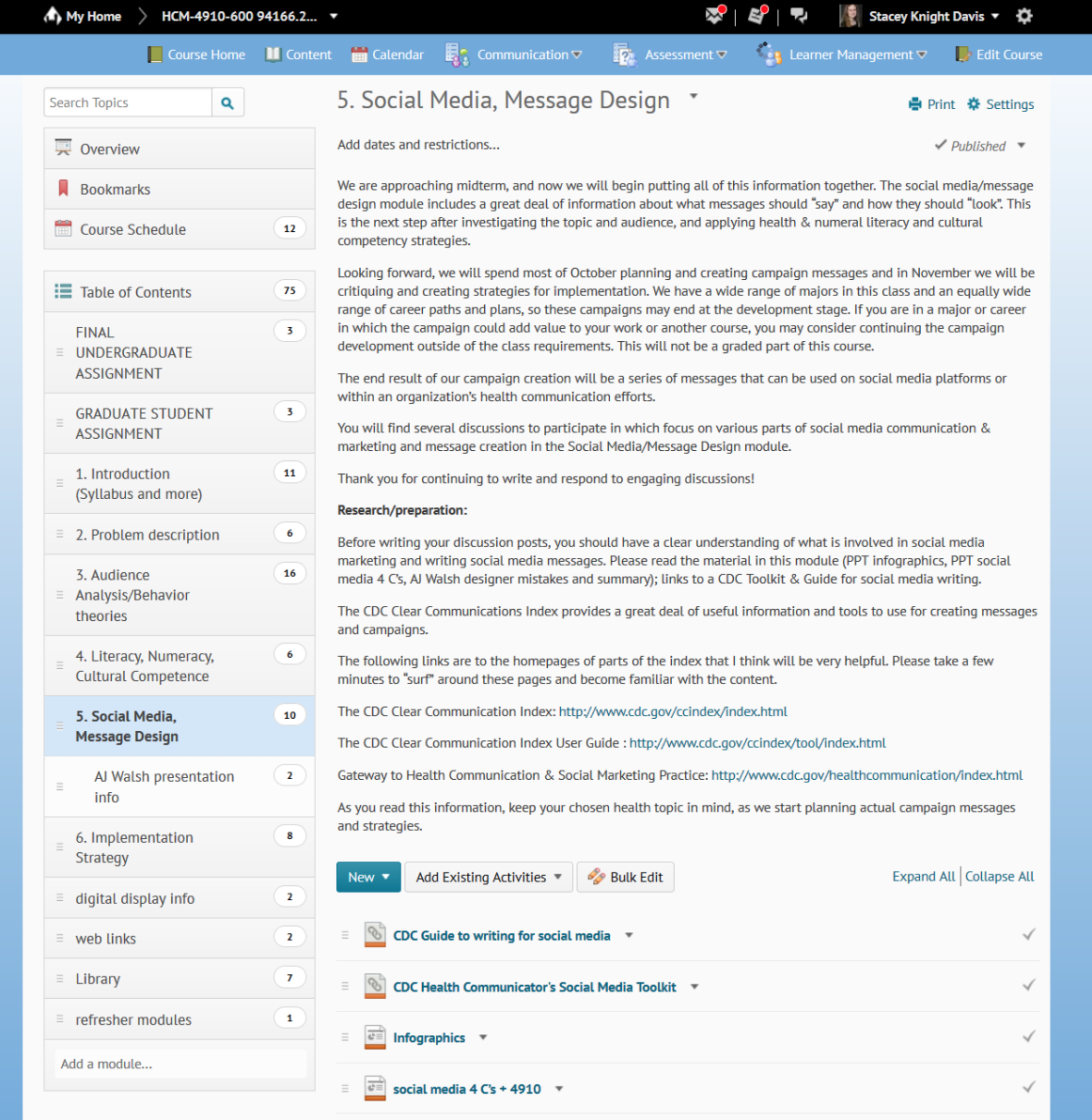

In our LMS we include video links, online training modules, and library modules. The instructor builds the general tools, such as the CDC resources, directly into the instruction module (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Module 5: Social Media, Message Design. From HST 4910 Applied Health Communication.

Reprinted with permission.

The tools and resources presented in the module fulfill the role of a textbook by providing standardized presentation of content. The instructor selects the resources that best fit the course concepts, and can mix from a variety of sources. If a source goes out of date, a new source can be added.

Our university offers a textbook rental program that is sometimes criticized because most students do not purchase their book at the end of a course. Some professors believe that not keeping the book robs students of their “intellectual dowry.” With freely available resources, students have access to the materials at no cost after graduation. This is a great advantage, as students have learned to navigate and utilize free resources, and are not reliant on an expensive textbook or handbook, which may also become outdated.

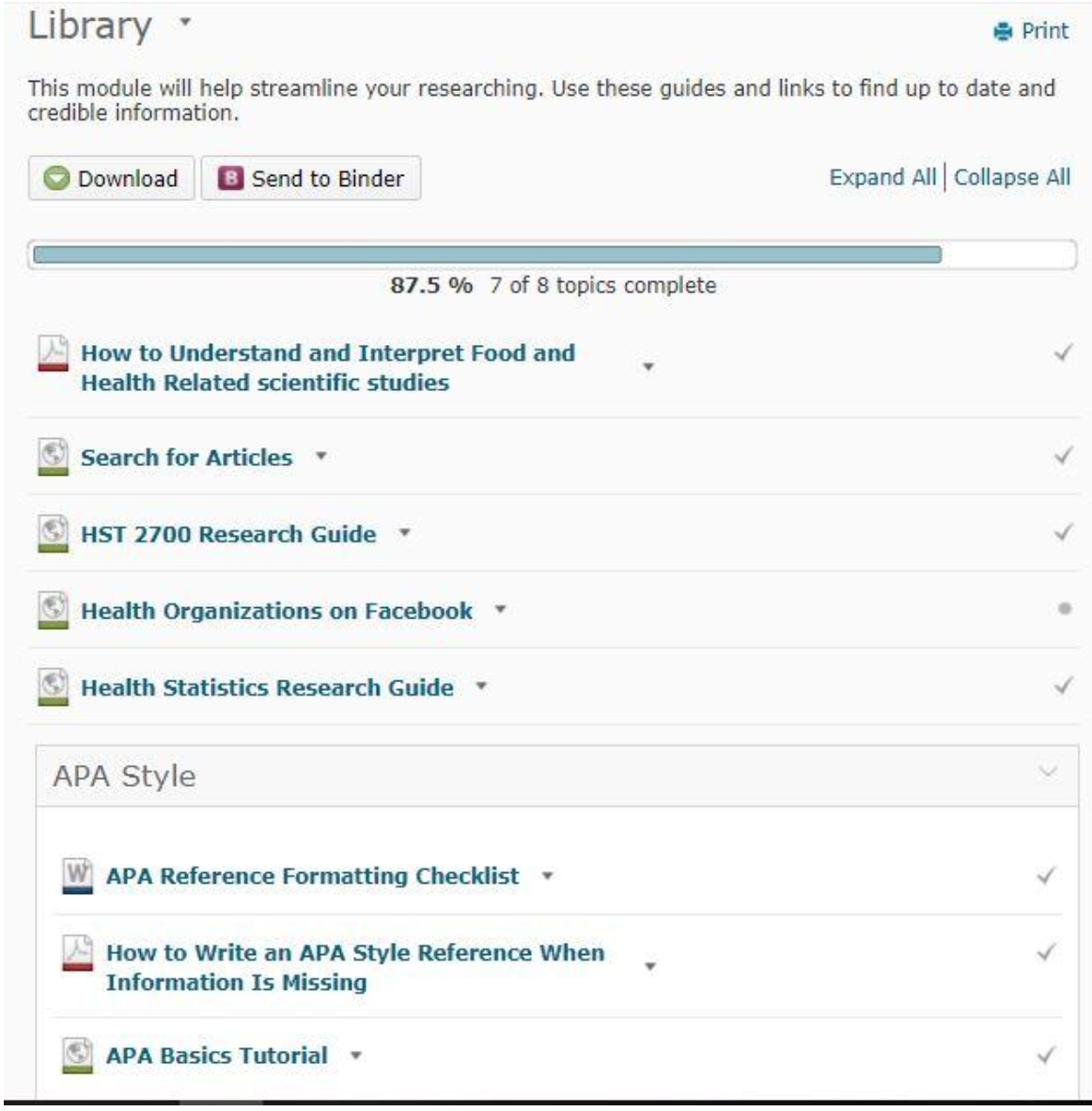

For information needs unique to each project, the library supplies electronic books, electronic articles, and streaming videos within the library module included in the course’s LMS. This model has been expanded to several other Health Promotion courses, providing supplemental readings at no cost to students. The library module consists of several pages that vary from course to course, but all include a “research guide” specific to the course, providing a portal to article indexes and full text articles, search tools for electronic books, and curated lists of titles appropriate for the course.

As mentioned earlier, we are always conscious of the resources our students are likely to have available once working in the field. PubMed, for instance, is a freely available index. We also highlight the Public Library of Science journals to familiarize students with providers of open access content.

Article search boxes provide semi-unstructured access to information. Our library does not have a single search tool covering all of our resources, so some artificial division does result from combining content from several different commercial providers. The majority of our article content comes from EBSCOhost, so the guide provides a customized search box that pulls articles from CINAHLPlus with Full Text, Business Source Elite, Health Source: Nursing/Academic, PsycARTICLES, and the Professional Development Collection. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of health communication and health promotion, and the intersectional nature of many health problems, this selection of databases was identified by the librarian as providing coverage for most topics the courses might touch upon.

Our approach to the EBSCOhost search is a balancing act. We provide a search box whose functioning simplifies the actual available resources. Students don’t know about the underlying databases, and likely could not build a comparable combination without librarian assistance. The search function constrains the problem, and provides some structure. By pre-selecting appropriate resources, the librarian allows students to devote energy to evaluating articles instead of struggling to find the right databases and learning how to combine them effectively. Search results open in a new window, so students can easily return to the screen where they started.

The PubMed search box also includes some mediation from the librarian. The PubMed URL is constructed so that articles not immediately available through the library’s licenses can be filtered out. Interlibrary loan links are displayed, while links to unsubscribed full text are suppressed. These modifications make PubMed function differently from what students will encounter outside of their classes, but the added convenience and functionality are more beneficial than the exact mimicking of a setting in which a health educator has to work without library support.

Each resource guide concludes with a curated list of resources chosen by the librarian to fit the course syllabus and assignment. Electronic books are preferred, as they allow courses to be fully online. (The library does mail books to students, but instant access electronically is strongly preferred.) Resource lists are separated by topic and reviewed regularly. Unfortunately, searching inside ebooks is an area for which the librarian cannot build in much customization. While the online catalog provides searching at the title level across all ebook providers, it cannot search inside the full text of electronic books. To get full text searching, students must use each provider’s platform. We have tried to streamline this by providing search boxes, but the process is more fragmentary and unguided than is ideal.

Library Support

Libraries need a robust technical infrastructure and well-developed collections to provide support for courses without textbooks. Excellent communication between faculty member and librarians is also a must. A faculty member must first describe the course and the anticipated information needs of its students. The librarian will then need to know about assignments and the topic areas to be explored.

Libraries need a robust technical infrastructure and well-developed collections to provide support for courses without textbooks. Excellent communication between faculty member and librarians is also a must.

Once these anticipated needs are established, the collection must be evaluated to make sure that appropriate search tools, articles, books, videos, and other materials are available. Web resources beyond those selected by the instructor should also be identified, and the instructor and librarian must check these resources regularly to ensure that the links are still working properly.

Identified sources must then be aggregated for ease of exploration and use by students. A content management system such as SubjectsPlus (University of Miami Libraries, n. d.) or LibGuides greatly simplifies the process of creating resource guides for classes or assignments. Content management systems allow reuse of content over multiple guides, so an article search box developed for one class can be dropped into the guide for a similar class. SubjectsPlus is distributed under a GNU GPL license, so it is in keeping with the spirit of Open Access and open educational resources (OERs).

The challenge with creating guides is to steer students toward useful content while leaving room for them to develop their own search skills. One approach, described above, is to provide an article search box that targets a pre-selected group of databases appropriate for the class, and then provide a selection of books and ebooks for students to browse. Since health promotion is an interdisciplinary field, students can struggle to identify useful books. Providing a list of selected titles lowers the barrier for exploration.

Distributing the targeted resource guides though the library’s website is helpful, but it is best to embed the guides directly into the LMS. We use an iframe to insert the guides into a library module for each course. The content stays on the library’s servers, and the librarian is responsible for edits and updates. The librarian is also added to the course, with limited permissions, through an instructor account, so that material can be added to the library module as needed.

Embedding the guides into the LMS does require some special configuration on the library side so that students do not have to authenticate several times. Remote access systems such as EZProxy allow students to use library resources from off campus. The library’s remote access system should be configured to treat students coming from the LMS as if they are on campus, so they do not have to authenticate to access library resources linked inside the LMS.

Developing Faculty-Librarian Collaboration

Opening a dialogue between the instructor and the librarian is the key to collaboration. Either can reach out to start a conversation. Regardless of who does so, it is key to have the instructor describe the course, and the librarian discuss how the library can support it. In some cases, a team of librarians may be involved. In our case, the health subject specialist happens to be the technology specialist, so no outside expertise has been needed to create custom tools. Most large academic libraries have a subject specialist assigned to each department. If this specialist does not have the needed technical expertise, the librarian should seek out an expert and build a team to meet the instructor’s needs.

The secret to collaboration is to start talking. Faculty should keep an open mind about what is possible from the library, while librarians should listen carefully and keep an open mind to developing new services and systems.

Assumptions held by librarians and instructors can be a barrier to communication. Instructors may assume that the library does not offer a desired service, or that librarians are too busy to offer in-depth support. Librarians may assume that, if instructors have not requested assistance, no services are needed. These barriers fall quickly once communication starts. The secret to collaboration is to start talking. Faculty should keep an open mind about what is possible from the library, while librarians should listen carefully and keep an open mind to developing new services and systems. It has been our experience that these potential barriers can be eliminated quickly, and that collaborative efforts greatly enhance the information available to students. Students can avoid the frustrations of doing a generic “Google search” that may generate hundreds of thousands of hits in only a few seconds. Since the introduction of the library modules to our LMS, the quality of information students include in their assignments has improved.

Open Access

In further support of Open Access, selected capstone projects are added to the University’s institutional repository The Keep, which is operated and managed by Library Services. By publishing student work in this repository, we allow projects to extend beyond a single class and classroom. Ideas constructed in the course are shared both at our university and around the world.

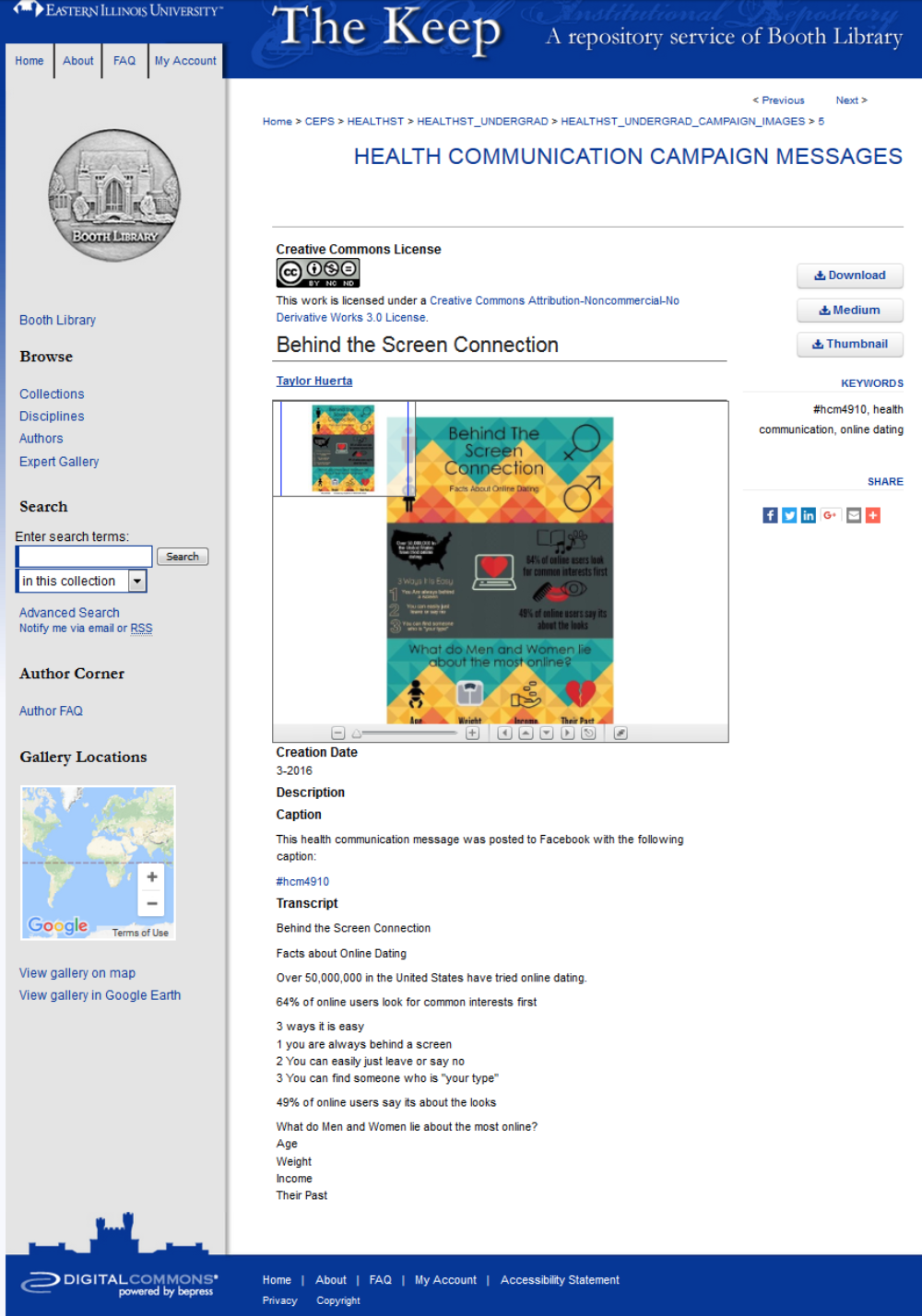

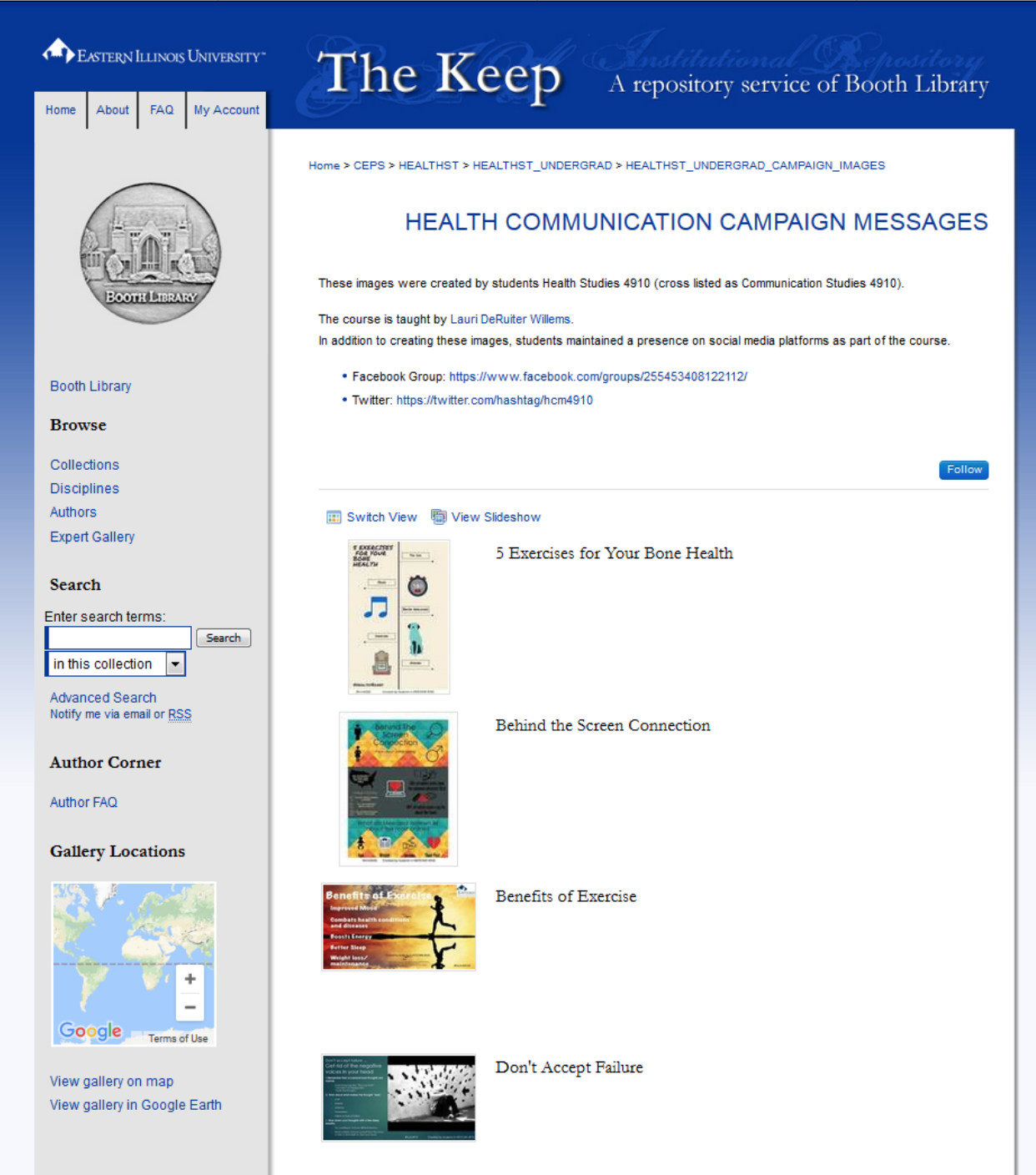

Student work from HST 4910 was first posted in May, 2016. (Student work that included images that the student did not have permission to reuse was not posted.) The initial collection included 17 works. The collection has been viewed about 40 times in the since it was uploaded. Figure 3 shows the first page of the collection, which also includes links to project components on social media.

As shown in Figure 4, each image in the collection is covered by a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Students typically submit their projects as image files, which are converted to JPEG format for upload to the repository. Each image is manually transcribed to provide search engines access to the text in the image, and key words selected by the librarian are applied to enhance discoverability.

Figure 4. Health Communication Campaign Messages. From http://thekeep.eiu.edu/healthst_undergrad_campaign_images/

Challenges

One of the challenges of this “non-textbook” approach is the ongoing process of ensuring that resources are still available. Because webpages are not static and regular updates are not guaranteed, they must be continually checked to ensure that the information provided still meets the instructional needs of the instructor and course. Web links must also be checked for accuracy—a potential barrier for courses using a common syllabus and/or multiple instructors. In the Department of Health Promotion at EIU, faculty worked with the librarian to make each course library module look similar, making their use easier for students enrolled in multiple health promotion courses.

Our librarian has worked diligently to make the information available to students without the need to log in to the university system multiple times, but there are occasions when student access is limited by browser and plugin issues. As our society is rather dependent on easy internet access, this can be frustrating to the students as well as instructors. It will continue to be important for both instructor and librarian to communicate any access issues.

Benefits

A key benefit to this approach is that the materials selected for the course are the same types of resources students will use once they are employed. Many community health practitioners do not have access to a research-level health science library, so we stress resources that are freely available. Teaching critical evaluation of sources is a skill that immediately transfers to professional practice. This approach also encourages critical thinking to integrate information from multiple sources.

Lessons Learned

Lessons learned from this approach are many. We feel confident that our students have access to the most current information in the field and will be able to use these resources in future courses as well as in internships and jobs. We know that this approach adds work time for the instructor, but we do not view this as a negative; the field of health promotion is ever evolving and instructors must keep up to date.

References

Centers for Disease Control. (2016). CDC Guide to writing for social media. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/socialmedia/tools/guidelines/guideforwriting.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2017a). Diseases and conditions. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions/

Centers for Disease Control. (2017b). Health literacy for public health professionals. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/training/index.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2017c). Healthy living. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/HealthyLiving/

DeRuiter-Willems, Lauri J. (2017a). HST 2700 – Marketing concepts for health promotion

professionals. Retrieved from http://thekeep.eiu.edu/healthst_fac/5/

DeRuiter-Willems, Lauri J. (2017b). HCM 4910: Applied health communication. Retrieved

from http://thekeep.eiu.edu/healthst_fac/6/

Foshay, W. R, Silber, K. H. & Stelnicki, M. B. (2003). Writing training materials that work. John San Francisco, CA: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Simon, Herbert A. (1977). The structure of ill-structured problems. In Models of discovery (pp. 304-325). Dordrecht, Holland: Pallas.

University of Miami Libraries. (n.d.) SubjectsPlus. Retrieved from http://www.subjectsplus.com/

University of Minnesota School of Public Health. (2017). Module 1: Beyond access. Culture and health literacy modules. Retrieved from https://cpheo1.sph.umn.edu/healthlit/

USAGov. (2017). U.S. Government Works. Retrieved from https://www.usa.gov/government-works

Author Bios:

Lauri DeRuiter-Willems is an instructor in Eastern Illinois University’s Department of Health Promotion. She combines her educational and professional experiences in health promotion and wellness in her teaching. Current teaching and research focuses on social marketing, health communication, health literacy and social media marketing. Ms. DeRuiter-Willems joined EIU in 2006.

Stacey Knight-Davis is the Head of Library Technology Services at Booth Library, Eastern Illinois University. Professor Knight-Davis also serves as the Bibliographer for Health Promotion and Nursing. She joined the EIU faculty in 2002. Her current research area is developing collections and services that expand role of institutional repositories.