Creating and Publishing Openly Licensed/Open Access Content

Chapter 24 – Collaborative Assessment Authoring: Building Alliances Across Consortia to Create and Share High-Quality, Open Assessments With the World

Liv Gjestvang, Ashley Miller, and Alexis Duffy

by Ashley Miller, Alexis Duffy, and Liv Gjestvang (all Ohio State University) (bios)

Introduction

In the summer of 2017, The Ohio State University (OSU), Unizin, and the Big Ten Academic Alliance (BTAA) held the first Content Camp, a collaborative authoring event to quickly create textbook-agnostic test banks at scale. The event, which was more than two years in the making, used a web-based tool to streamline the process of authoring, revision, and quiz creation. After successful completion of three test banks for macroeconomics, medical biology, and sociology, OSU began working with Penn State University to develop a new tool to make the process even easier, and has already piloted the new product in a second event in the spring of 2018. This chapter details the history, reasoning, planning, and results of that project.

History

In December, 2015, a group of learning technology leaders in the Big Ten Academic Alliance identified affordability and open educational resources (OERs) as core topics of interest, and in January, 2016, authored the following problem statement around Affordable Content:

Designing programs to engage our campus communities in learning about and creating (or adopting) low or no cost content is a commitment we share across campuses. In addition to sharing this commitment, we benefit greatly as a consortium if we design clear, streamlined ways to share the successful models, programs and platforms we have created on our individual campuses, so they can be adopted and scaled across the Big Ten.

The following month, a group of more than 40 educational technology and other academic professionals met as part of the Teaching and Learning committee within Unizin, a consortium of 11 research-focused institutions committed to addressing some of the most critical issues facing higher education today, including learner success, access, and affordability. This team articulated a commitment to “Improve student learning by increasing access to affordable high-quality course content and analytics” through a strategy of “Encourag[ing] creation, adoption and adaptation of high quality course content (interactive digital texts, adaptive learning modules, videos, problem sets, assessments, etc.) to increase affordability, quality of content, student learning, and access to analytics and data.”

While both the Big Ten and Unizin groups articulated similar goals and were driven by an equally strong commitment to free and open content, neither had existing structures in place to leverage faculty from across disciplines and institutions to collaboratively author and review high-quality content. At OSU, however, the Affordable Learning Exchange team had identified a model for open content development that could leverage both of these large consortia to drive the shared development and dissemination of open content.

The Challenge of Ancillary Materials

Setting the Scene

OSU’s Affordable Learning Exchange (ALX) was created to help instructors take ownership of their courses and content. Our team believes that the cost of textbooks shouldn’t be a limiting factor in student success, especially when there are high quality open and affordable alternatives to conventional, high-cost textbooks. Our mission is to help faculty navigate the waters of affordable resources and find creative solutions that promote student savings. This includes re-imagining the textbook, encouraging faculty innovation, and empowering faculty through grants and training opportunities to adopt, adapt, create, and share OERs.

Among these familiar challenges, however, we heard another concern that was new to us: the threat of lost ancillary materials like slides and test banks.

When recruiting applicants for our grants-based support program, we hear recurring arguments from faculty against adopting OERs that won’t be surprising to anyone reading this chapter—they don’t have time to undertake such a large project, they’re uncertain about the quality of available open textbooks, and they can’t take time away from research or service obligations to focus on teaching. Among these familiar challenges, however, we heard another concern that was new to us: the threat of lost ancillary materials like slides and test banks. While we knew these materials were heavily used in many courses, we didn’t realize the impact of this loss at an institution the size of OSU—with class sizes routinely reaching into the hundreds—until we talked to the faculty teaching these large classes, and realized that even highly motivated faculty who can overcome the “usual” barriers to OER adoption are often limited by dependence on these ancillaries.

What Students Said

A series of focus groups held in the fall of 2016 at four of OSU’s regional campuses gave us additional insight into the pervasive nature of these instructor supports, particularly test banks. We held these focus groups after faculty raised concerns about student access to and experience with digital materials. We talked to 35 students, asking the following:

- How much did you spend on textbooks this semester?

- What are some strategies you’ve used to save money on textbooks?

- How would you describe your comfort level using technology?

- How would you describe your experience using digital books and other online course materials at home or in the classroom?

- What kinds of barriers do you encounter accessing digital books or course materials?

- Is there anything else important on this topic that we haven’t talked about?

Key Findings

We found that students in these groups were typically spending between $300–$600 per semester on textbooks and access codes. All of them had access to technology, at home or on campus, and were routinely required to use digital course materials. Most reported that they were comfortable with technology. Several described having to buy both a book and an access code, although they often had no assigned readings from the textbook, but were instead pointed to the homework system and digital materials bundled with the purchase.

These conversations satisfied our initial mission, but opened up new concerns about this apparent reliance on ancillary materials. While we don’t have the resources, time, or knowledge to tackle a complete solution to overcoming the barrier of all online course supports, we did feel that we could tackle one big part of the problem: large test banks.

It is worth noting that, while we heard a great deal of feedback regarding homework and online assessments, none of our questions explicitly sought this information. We had thought of assessment as an instructor issue—each instructor having the responsibility to design, administer, and grade assessments in his or her own courses. But thanks to these student focus groups, we recognized the extent to which instructor and student experiences are intertwined, and how instructor challenges can seep into the classroom experiences for our students.

Instructor’s Experience as Opportunity

Dr. Darcy Hartman was a grant winner in the Affordable Learning Exchange’s initial cohort in 2015–2016. At the helm of a 1,200-student macroeconomics course, she was working to replace the $220 conventionally-published textbook. She conducted a review of the OER landscape in macroeconomics and settled on an openly-licensed textbook. But as she prepared her new materials for class, she found that she would not be able to adequately assess her students’ knowledge throughout the semester without the test banks that come packaged with textbooks. She thus made a last-minute switch to a publisher that packaged her new open textbook with the ancillary materials she needed and charged students between $25 and $60 for access (based on the file type and access level selected).

Dr. Hartman was still interested, however, in cutting her students’ cost to $0. Her need for an open and free test bank provided the impetus we needed to tackle this new problem.

The Big Idea: Content Camp

It became clear to us that, to encourage more widespread adoption of OERs, we needed to address the problem of ancillaries, and test banks were a good place to start. We decided to use collaborative authoring to create multiple test banks large enough to be used for more than one semester, in more than one class. As we began considering an approach, we identified the importance of shifting focus away from authoring assessments for specific textbooks and towards aligning assessment questions with overarching learning objectives that represent content shared among similar courses. This approach allowed us to create comprehensive test banks organized by topic and learning objective, with wide appeal across all types of users and institutions.

It became clear to us that, to encourage more widespread adoption of OERs, we needed to address the problem of ancillaries, and test banks were a good place to start.

To kickstart the creation of these banks, we decided to host the first Content Camp, an in-person, professional development opportunity for faculty from across the US, combining instructional design guidance with content creation in a group setting.

Textbook-Independence for Wide Adoption

We quickly realized that organizing the test banks by learning objective would allow faculty to easily navigate and adopt questions from banks regardless of their textbook or learning materials. In fact, the first task we assigned to the faculty leaders recruited for our Content Camp project was to prepare a list of fairly granular objectives, organized by topic, that could be used as guidance for assessment items. (As we’ll discuss later in the chapter, asking faculty to start at the objective level for this project eventually changed our approach to every project the ALX has managed since.) We also wanted to build peer review into the collaboration process, adding a level of credibility to the final product that is missing in paid products currently on the market.

Building Community

Through our work within the Big Ten Academic Alliance and Unizin, we had been participating in conversations since 2015 about how to leverage faculty from across institutions to collaboratively author open content. The first Content Camp pilot was designed to leverage national faculty networks to create a product that could be used in any course across the country. We wanted to include faculty contributors from a wide range of universities to identify and address a range of approaches to course organization and a broad spectrum of teaching styles, ensuring that our product was agile enough to work with as many instructor nuances as possible.

Figure 1: The macroeconomics team working together at the Content Camp pilot in June 2017. Clockwise from the bottom left: Jeffrey Barr, Kaitlin Farnan, Alexandra Nica, Darcy Hartman, Marzi Bolhassani

Our vision of the product beyond this initial pilot also relied heavily on the development of an engaged community. Our ultimate goal is to build an open online resource in which instructors can regularly access and author new questions, which will be reviewed by other users who are experts in their disciplines. To keep the bank growing, we’ll need a large number of highly-engaged users across the disciplines who are revising and improving both individual questions and, ultimately, the bank itself.

A Focus on Quality and User Experience

Having determined that the success of such a product depended on the quality of the assessment items and the user experience, our team decided that faculty development should play a major role in our in-person pilot event. We recruited a member of OSU’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching to attend and lead sessions on the authoring of both objectives and questions. We believe that educating question authors about what makes a fair and well-composed question will help build a bank of material that will be reliable, will test knowledge appropriately, and will require little editing on the part of the end-user.

Another layer of credibility is added to the test questions by the end-users themselves. It is our vision that, as they browse and search for questions that are organized by topic and objective, they will be able to rate, suggest modifications to, and comment on questions. They will be able to see which questions are the most used and most highly rated, and view suggestions on usage from instructors who have used the questions themselves. This community will lean on each other not just by building the bank, but by continuously adding to, refining, and improving the library.

Because the quality of our content depends so heavily on the user community, it is vitally important to construct a reliable user scheme. Before they are granted permission to author or modify questions, users will be required to demonstrate that they are active in a particular discipline. While we have not yet worked out the specifics of this process, we imagine it could include the submission of a CV or a link to a department website that clearly lists the user and his or her role at the institution. This way, questions are sure to come from subject matter experts themselves. Any user, however, will be allowed to create and download quizzes in any discipline.

These quizzes will eventually be available in a variety of downloadable formats. The first version of the tool will allow instructors to download a quiz in QTI format, which will easily upload into learning management systems (LMSs) like Blackboard and Canvas. Eventually, we’ll expand to other file formats and add a function that will allow users to export a quiz or bank into a Word document.

The Affordable Learning Exchange is committed to making the final product and its contents as open as possible. For the first stages, we intend to limit access to instructors only; any instructor can join, and will then be able to author or revise questions and create and download quizzes.

We have discussed the open licensing of the product and its contents at length, as its specifics present a host of unique challenges. While we want the bank to remain as open as possible, we also want to ensure that faculty members receive credit for their contributions, and that their material is protected from third-party commercialization. Any attribution license from Creative Commons requires that the end-user be able to see the original author. After speaking with the Creative Commons legal team at length, we have determined that in this case the ultimate end-user is a student taking a quiz. Frankly, attributing each question is a cumbersome notion, and one that does not serve our audience. Instead, OSU and Penn State are working together to develop clear licensing language that allows free usage among instructors, and ensures that a third-party cannot absorb the original content and profit from the work of our faculty. While this licensing approach does not fit neatly into any of the available standard Creative Commons license options, it will ensure the content is openly available for free use and remix by anyone for non-commercial purposes. Site users will be credited for their activity on the site as well (including authoring of original questions, commenting, editing, and remixing).

Many instructors and educational technologists have expressed concerns regarding student access to the bank. For the first stage, our plan to restrict access to instructors only will avoid this issue. If we later decide to remove that barrier and make the bank truly open, we feel that, with the vast number of questions we are aiming to include, it would be nearly impossible for students to cheat. If they did go in and memorize thousands of questions, then they are in fact learning the material—which is, of course, our ultimate goal in helping instructors build quizzes.

Content Camp Logistics

Program Model

Content Camp was designed as a three-month process, starting with an initial six-week phase during which authors developed and reviewed a significant list of course objectives in their respective disciplines. Faculty teams met virtually to discuss expectations, review the process, and outline logistics for an in-person event at the Big Ten Center in Chicago. The in-person event allowed faculty teams to connect face-to-face to finalize their shared course objectives, learn about psychometrics and best practices in assessment authoring, and begin authoring and reviewing assessment questions using the tool. The final phase of the authoring process spanned the summer, with each faculty author writing and then reviewing questions for the bank.

Recruitment

To recruit participants for the Content Camp Pilot in June, 2017, we first gathered faculty with an interest in collaboration and a willingness to try something new. They also had to have time. We reasoned that a test bank should have approximately 1,000 questions in order to be large enough to be flexible. Recruiting faculty teams of five, we asked that each participant be responsible for authoring and reviewing 200 questions.

Aside from macroeconomics, the course which was the impetus for the project, we weren’t yet sure which disciplines to focus on. Thinking that we could build test question banks for two other disciplines at the same time, we put together a brief project description with a rough timeline, and reached out to learning technology peers at other Big Ten Academic Alliance and Unizin institutions to ask for their help recruiting interested faculty. We expected that people in educational technology leadership roles would be likely to know which faculty would be interested in the exploration and the trial and error that comes with a pilot experience.

Teams were designed to have one Team Lead, and four Content Contributors. The Team Leads began their work first, each proposing a list of learning objectives that would represent all of the material covered in an introductory course in his or her discipline.

This relatively flat hierarchy, with a leader who has a dual role as contributor, helped distribute the project management workload. Meetings were scheduled twice monthly between the Team Lead and an OSU Affordable Learning project manager, and monthly meetings were held with the entire team. Though these quick check-in meetings lasted only 15 minutes or so, they served as an important part of the process, keeping lines of communication open and the team on task throughout the project. We also encouraged more frequent communication between team members, but allowed each Team Lead to negotiate the terms of that communication based on team dynamics.

Lessons We Learned

Faculty Incentives

Team Leads were offered a $3,000 stipend, while Contributors were offered $1,200. These stipends were paid for by the contributor’s home institution, while in-person meeting expenses and lodging were paid for by OSU.

Team Leads had a small amount of additional work, which included proposing disciplinary objectives and serving in a leadership role throughout the process. This often meant checking in with our administrative team, and with their own.

Aside from the monetary compensation, the team members we worked with had a general enthusiasm for innovation in teaching and learning. They also gave positive feedback after working through the session on question and objective writing, sharing that they had not been trained in these areas before, and were grateful to engage in these conversations with peers.

Project Management Approach

We believe that a large portion of the value we bring to faculty who are undertaking any kind of OER authoring/remix project is in our established, agile project management support. For Content Camp, we added an important component to this process, which we’ve since extended formally to the rest of our projects: faculty leadership.

We recognize our inability to anticipate all faculty needs in the process, so asking faculty to tell us what supports they need is important. We’ve also observed that teams often prefer to take direction from their peers, rather than from us, and we feel that this builds both camaraderie and (we hope) lasting connections.

Teams decide how often they meet, and who (based on expertise) focuses on particular objectives. They also determine the pace of the work; we check in to hear about their decisions, remind them of their timeline, and gauge progress based on those decisions. We are not content experts, nor are we close enough to their comprehensive workloads to weigh in on these decisions, but we are well situated (and appreciated) as neutral observers and resources for questions—we connect them with the information or expertise they may need and help them organize their work.

Piloting the Process: Timelines and Templates

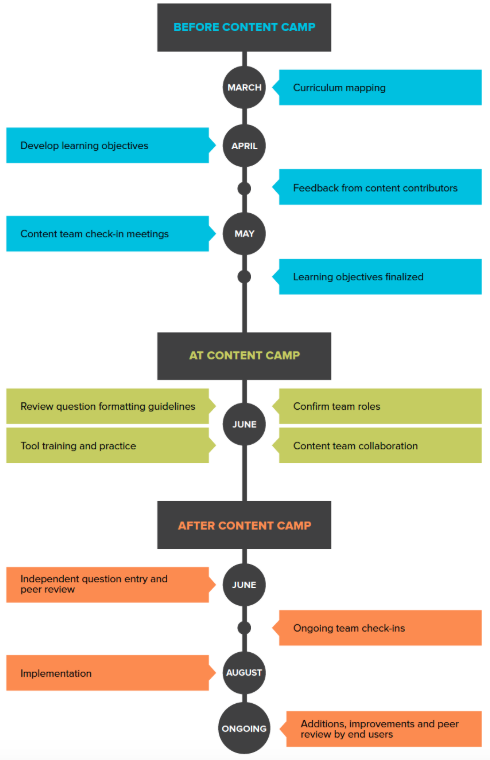

Figure 2 shows our initial timeline. In reality, recruitment didn’t fully wrap up until early May. Recruitment for contributors did not slow the objective writing process, and we began meeting with Team Leads as soon as they were recruited.

Each participant completed a memorandum of understanding, which briefly outlined their responsibilities, the final deadline, and their stipend. The document was administered through a Google Form for easy tracking.

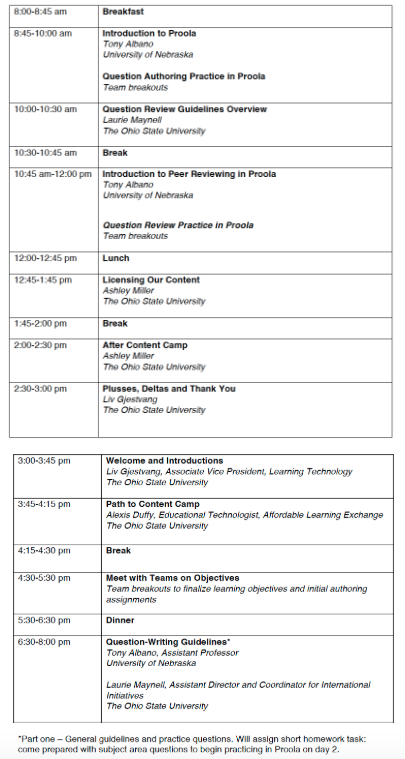

As we moved closer to the event, we developed an agenda. We divided the hours we had together into chunks of time dedicated to specific tasks, including professional development on the authoring of objectives and questions, training on use of the tool, and plenty of work time for the groups. This agenda is outlined in Figure 3 below.

Discipline- and Team-Specific Outcomes and Challenges

Despite having received the same training and instructions, the disciplinary teams produced vastly different products. The macroeconomics team, led by Dr. Hartman, started with approximately 130 objectives, and easily divided up the authoring amongst the team members according to their expertise. The medical biology team ended up with approximately 500 objectives; while this made question authoring very clear, it was difficult to cover all of the material and to develop more than a question or two per objective. The sociology team, in contrast, compiled a list of just 20 objectives; as they sat down as a team to write, they realized that their objectives weren’t specific enough, making it difficult for them to author questions.

Some disciplines, including economics, may be more naturally suited to translation into objectives, while others, like sociology, may be more nebulous. But since a standard aspect of teaching is identifying course goals and objectives for students, this process should be echoed in the creation of fully representative objective lists.

Because of this experience, we recommend that teams aim for around 150 objectives per course. Again, these are meant to represent the material covered in an introductory course, and resemble a textbook’s table of contents, but this does not mean that every instructor covers every topic or objective. Our goal is simply to provide content that instructors can use to support their unique course goals. The selection process remains in instructor hands.

Piloting a Tool

Requirements

As we developed our plans for the pilot, we started looking for a tool that could facilitate the collaborative authoring process. We began by examining the current process that instructors like Dr. Hartman go through to use test banks from publishers. Typically, instructors are delivered a Word document that contains hundreds of questions, often organized by chapter and sorted by question type. To use these questions in their LMS, instructors must copy and paste the desired questions into the corresponding fields, or format and use third-party software to generate a file that can be ingested by an LMS. There is no way to easily search, sort, and save questions.

We began looking for a product that made this easier. Our ideal tool would allow users to author their own questions, review the questions written by other authors, and ultimately search for questions, create quizzes, and export those quizzes. A tool like this has three advantages:

- Adding a peer-review function into the authoring process ensures that test questions will be of higher quality than those packaged with publisher materials.

- Searching for questions and building tests happens outside of an LMS and employs technology that allows users the ability to search by keyword or browse by objective.

- Uploading a created quiz into an LMS like Canvas is a much easier process than sifting through an entire test bank that has been already been imported into an LMS.

User Feedback

Throughout the event, we collected feedback on the tool via a Google doc that participants could update live. We also held several meetings with content teams after the event wrapped and while they continued their work over the remainder of the summer.

Overall, the foundation of the tool was well-received, and participants reported positive feedback regarding a keyword search function and the review capabilities. On the other hand, users found the tool difficult to navigate for review or test building. Eventually, it became clear that this particular tool was not a good match for the higher education audience with which we had tested it.

We found many of these requirements in an open-source tool created by an expert in psychometrics, who agreed that we could use his tool to facilitate our work in the pilot.

Figure 4: Content Camp pilot participants from the top left. Tony Albano, Andrew Martin, Scott Lewis, Kevin McDade, Heath Tuttle, Jeffrey Barr, Melisa Beers, Alexandra Nica, Barbara Zsembik, Timothy Paustian, Marzi Bolhassani, Lindsey Chamberlain, Laurie Maynell, Alison Bianchi, Diane Kuharsky, Alexis Duffy, Darcy Hartman, Kaitlin Farnan, Ashley Miller

Lessons Learned and Evolution

Results

The first Content Camp pilot was completed in August, 2017, and resulted in:

- Three test banks, each with approximately 1,000 questions, for a total collection of 3,000 questions in the tool.

- A basic process that married professional development on student assessment with technology training.

- A clear idea of what a successful technology solution might look like, in order to effectively facilitate collaborative authoring, review, and test creation.

The planning and execution of the event left us with these major takeaways:

- An engaged group of instructors who have not previously worked together can, with moderate support, generate shared course objectives and hundreds of assessment questions in a short amount of time.

- Faculty participants are very appreciative of the opportunity to learn about and practice assessment authoring skills (most articulated that they had not formally learned these strategies in the past).

- A strong project-management team is critical to ensuring that faculty teams can land on shared objectives and deliver a 1,000 question bank within a few months.

- A well-designed, easy-to-use tool is a critical element in the authoring and review process when creating questions at large scale and with a rapid pace.

Ongoing Development and Goals

Thanks to the pilot, we better understood the critical role of a tool that effectively facilitates the writing, review, and quiz-making processes. Our use of the tool in our pilot helped us identify the most important technical capabilities, and we immediately put this knowledge to work as we started building a new tool in partnership with Penn State University. OSU continues to drive the process, including professional development and the strategy for and requirements of the tool, while Penn State leads the software development with its technical expertise. Our teams stay in touch with weekly one-on-one meetings to fine-tune and test, and the larger teams gather together monthly to check in on progress. OSU remains dedicated to hearing and incorporating the voices of the faculty.

The team has also moved forward in a partnership with the Big Ten Academic Alliance. Learning technology leaders across the campuses have affirmed their commitment to more affordable experiences for students, and have fully supported any collaboration that makes this happen. The BTAA is supporting interested institutions with funding and administrative fiscal support.

In May, 2018, we hosted an additional Content Camp event, with instructors traveling to build test banks for Introduction to Psychology and American Government courses. These instructors are not only acting as authors and reviewers, but are taking on a new role as beta testers of the tool in development. Test banks from this latest Content Camp will be ready in August, in time for the fall semester of 2018.

Closing

As the use of OERs continues to expand, it is important for those in university technology and pedagogical support roles to build out ancillary materials on which faculty can rely.

Our work with colleagues in the Big Ten Academic Alliance and Unizin spurred us to examine the question of how institutions can work together to expand the reach of OERs and affordable content, which led us to identify a concrete problem, iterated by both faculty and students, that served as a barrier to further adoption. With our background in faculty support, we recognized this as an opportunity to break new ground in collaborative development. The implementation of a pilot to develop an engaged faculty community, to provide faculty development, and to create and review assessment questions based on well-iterated learning objectives for specific disciplines provided us with new resources to support further development in this area. We were also able to recognize the importance of a two-pronged approach involving professional development and the facilitation of a web-based tool.

As the use of OERs continues to expand, it is important for those in university technology and pedagogical support roles to build out ancillary materials on which faculty can rely. We will continue working to refine the Content Camp process, and developing a tool to support the vast number of questions and users that we envision. Assessment is an important part of learning, and we believe that this project will not only reduce cost, but will improve that experience for both faculty and students.

Author Bios:

Ashley Miller is Program Manager for Affordability and Access in Ohio State’s Office of Distance Education and eLearning. She manages the Affordable Learning Exchange, which works with partners across the university to support faculty who wish to move away from conventional course materials in favor of low-cost and Open Educational Resources. She is passionate about transforming classroom learning experiences and helping to make higher education more affordable for students at Ohio State and beyond.

Alexis Duffy is the Projects Coordinator with Ohio State’s Affordable Learning Exchange. She holds degrees from Michigan State University, Emerson College and The Ohio State University. With a background in educational publishing, Alexis works closely with grant winners as they plan and implement affordable solutions, including writing, remixing and adopting open textbooks.

Liv Gjestvang joined OSU’s Learning Technology team in 2006 and has served as Associate Vice President since 2014. Her team leads enterprise learning systems, classroom technology, and faculty innovation support. She is committed to student access and success, with teams that lead OSU’s Affordable Learning Exchange, Digital Bookshelf, and the development of low and no-cost texts. She serves on the Unizin board, is chair of the Big Ten Learning Technology Leaders group, and co-authored College Ready Ohio, a $13.5 million grant from the Ohio Department of Education, supporting college readiness for high school students.