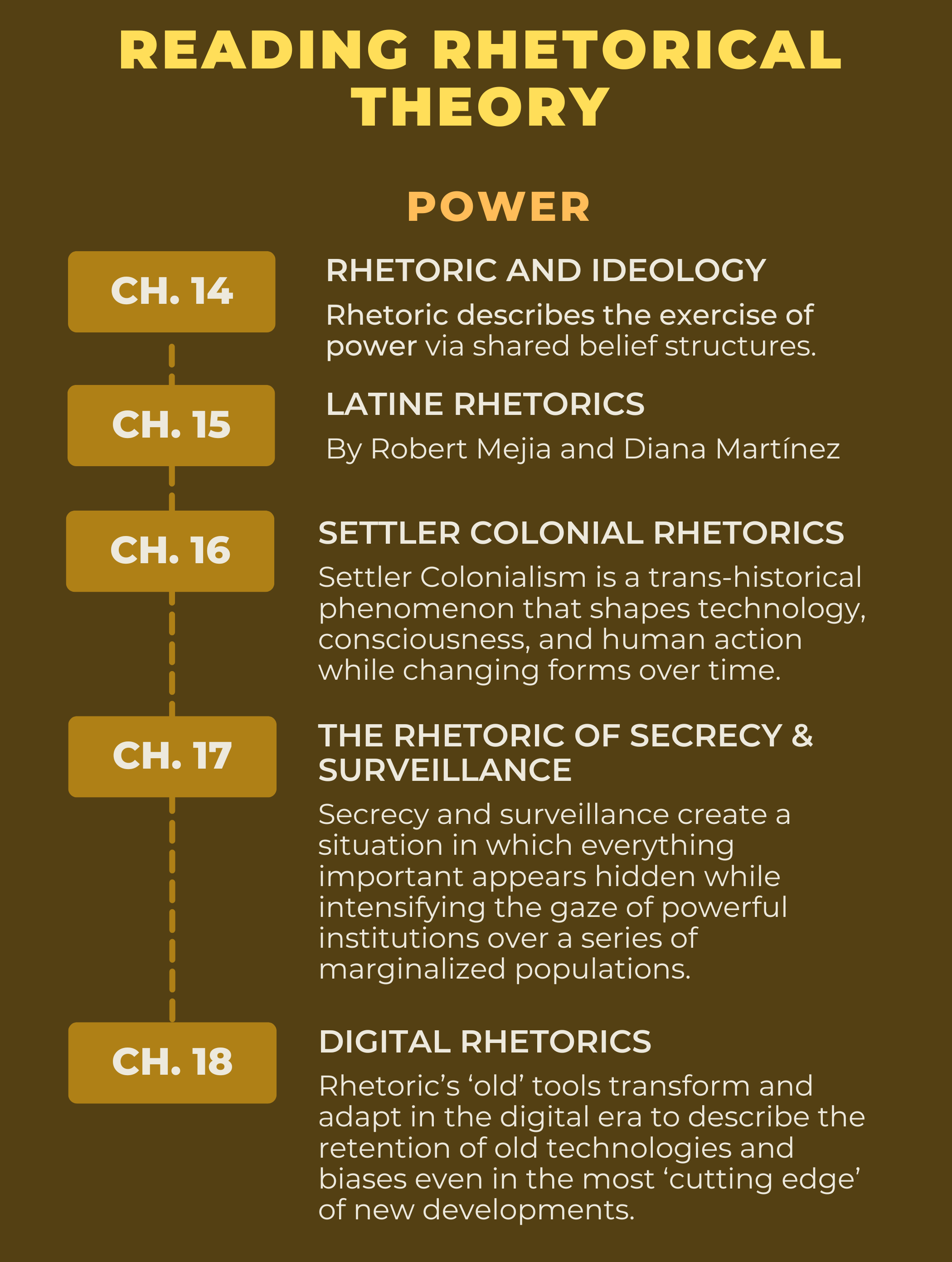

Part 3: Power

When we understand rhetoric as a function of power, it means that we acknowledge the effects that speech and representation have over a person, a community, or a public. As Kenneth Burke reminds us, rhetoric unites and divides; it allows a person to see their likeness in another person and it enables them to view their difference from others as a rationale for dissociation, alienation, and dehumanization. As theory, or a lens through which to see the world, rhetoric also offers us something more than a technique by which powerful agents exercise their influence. It also offers us a way to analyze how power is distributed, exercised, pooled, and deployed; it allows us to see that power is often not a matter of one person, institution, or group exercising unilateral control over a situation, but a complex coordination of many agents who wield leverage and control over a means of producing representations for a mass public. Often, power’s exercise is not felt but apprehended after the fact. The chapters collected under the heading of “power” are intended to offer frameworks for understanding different forms of communicative hierarchy and the subtle ways they exercise social control.

Why these Chapters?

Chapter 14 introduces the concept of ideology, a system of organized beliefs and actions that guide human activity according to a hierarchical structure of economic and governmental interests. Rhetoricians have engaged the topic of ideology in many different ways, as captured by this supplemental resource document. Ideology is rhetorical because it can be communicated through speech, as a function of widely disseminated representations, or as a complex coordination of institutions and technologies that produce communication across many domains of public life. The chapter investigates these distinct registers by exploring the concepts of persona, agency, and speech acts, creating a layered sense of how ideology textures and guides human action in ways that are beyond the conscious perception of those who are moved to act by it.

Chapter 15, Latine Rhetorical Theory (by Robert Mejia and Diana I. Martínez), explores what it means to rethink rhetorical theory as Latine rhetoric, drawing from the theoretical foundation of Gloria Anzaldúa. Latine rhetorical theory is much more than a widened scope of identity or representation. It accounts for a wholesale conceptual transformation of the core terminology, spaces, and relationships used to describe the situated experience of a population that resists generalization or capture by racially whitened systems of thought.

Chapter 16, on Settler Colonial Rhetoric(s) offers a unique perspective on rhetoric as a structure that stretches across millennia, adapting to the particular power structures of a given era. Settler colonialism not only shapes consciousness, attachments to land, and the narratives we tell. It also infiltrates such popular story-forms as science fiction, which allow those who are the historical benefactors of settler colonialism to imagine themselves on the receiving end of violence that their ancestors perpetrated.

Chapter 17, on the Rhetoric of Secrecy and Surveillance describes a ubiquitous situation in which everything that is important must be packaged in rhetorics of hiddeness, concealment, and revelation. Secrecy is a phenomenon attached to ancient imperial governments that continues to be used for the efficient management of populations. Even as secrets seem to spread to every domain of public life, keeping spectators on the hook for the next ‘drop’ of information, controlling interests intensify their grip over consumers, non-citizens, racially marked bodies, and those who refuse conformity with hegemonic gender norms through newer and more expansive technologies of watching.

Finally, Chapter 18, on Digital Rhetoric(s), discusses the ways that rhetoric is well-suited to describe our ever-more digital age. Although it may seem as though new technologies change everything and that old tools for analyzing and conceptualizing communication may have gone out of date, there are many lessons, terms, and concepts that remain very timely for understanding the false promises made by entrepreneurs and the threat of imminent destruction posed by cutting edge technologies. Ultimately, the more things change, the more they stay the same: new media is inhabited by the rhetoric of old technologies and old biases, which are coded in subtle ways even when new communicative forms are branded as ‘neutral’.