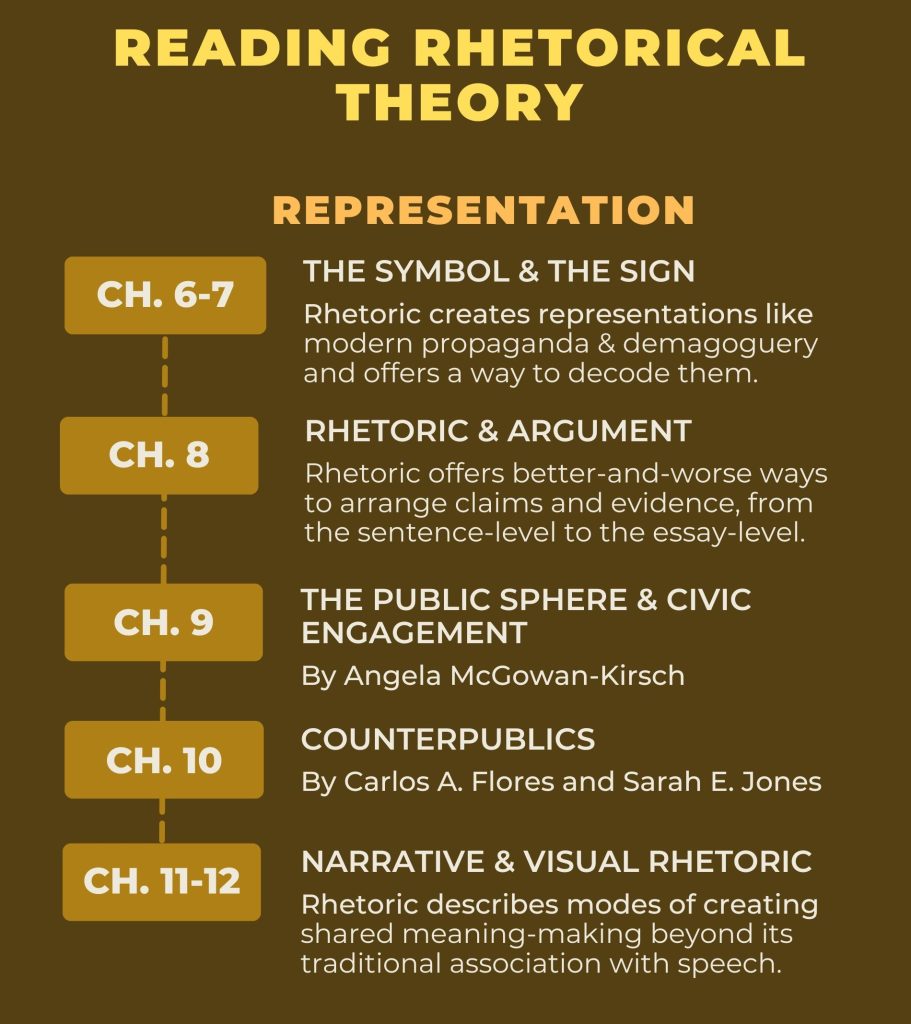

Part 2: Representation

To describe rhetorical theory as a function of representation can mean many things. It can mean that rhetorical theory is the theory of how representations are made, created, or manufactured for popular and public circulation. It can also mean that rhetorical theory is how we make sense of representations, offering guidance on how to interpret, decipher, or understand the meanings that circulate around us. In the chapters that fall under this heading, rhetorical theory is associated with key terms like “symbolic action,” “identification” and “meaning making.” As a function of representation, rhetoric also extends beyond speech’s spoken and written media, encompassing theories of the sign and the symbol, forms of arrangement like argument and narrative, modes of visual presentation, as well as specific spaces of circulation like the public sphere. Representation also describes rhetoric that enables groups to define their identities, boundaries, and communication practices. The chapters on counterpublics and Latine rhetoric take this question up, asking how we can rethink rhetoric from the ground up as a set of representation practices that are specific to a community.

Why these Chapters?

Chapters 6-7 depart from theories of rhetoric as speech, suggesting that language itself can shape how we think about and act in the world by virtue of the representations that are most available for popular consumption. Rather than intentional choices that a speaker makes to influence an audience, to understand rhetoric as inhabiting the field of representation means that the words, symbols, and images that are most available for our use come pre-loaded with significance, and that by using them, we contribute to an existing field of force-relations between ourselves and others we perceive to be unlike us. Importantly, symbols (Chapter 6) and signs (Chapter 7) are not the same! They have different philosophical underpinnings and have been used to theorize rhetoric in vastly different ways. The key to these chapters is that rhetoric can be speech but also more than speech, inhabiting the very patters of speaking, writing, and representing that we undertake without consciously reflecting upon them.

Chapter 8 offers a way of understanding rhetoric’s relationship to arguments — that is, claims, evidence, and the connections between them (or warrants). It offers an overview of the way that we might think of rhetoric and argument at the micro- and macro-levels; that is, as a way of organizing individual sentences or paragraphs as well as ways of organizing whole essays or even books. Such frameworks are the basis of organized debate, and provide coordinates not just for making arguments, but for recognizing how others are arranging information in order to achieve some effect through representation.

Chapters 9 (by Angela McGowan-Kirsch) and 10 (by Carlos A. Flores and Sarah E. Jones) describe the predominant way of thinking about the audiences of argument: as publics. The most conventional way of thinking about the audiences for arguments comes from Jurgen Habermas’s conception of “the public sphere,” a spatial metaphor for the way that arguments circulate and become accepted as common knowledge. As rhetoricians like G. Thomas Goodnight have argued, the public sphere sits alongside two other spheres: the ‘technical’ and the ‘personal,’ which have their own complex relationship to ‘the public.’ McGowan-Kirsch elaborates on the public sphere as a space for civic engagement, meaning that rhetoric is a way of employing representations that make a difference and demonstrate one’s stake in the common good. Chapter 10 describes a critical response to the idea of a singular public sphere: counterpublics, or spaces of resistive activity that stand apart from the singular (and often exclusionary) norm of ‘the public.’ Offering a range of examples and case studies, Flores and Jones describe the contingent, flexible, and multiple nature of counterpublics alongside key definitions of this concept.

Chapters 11 and 12 expand on the idea that rhetoric need not be only speech — or, for that matter, rooted in language, symbols, and arguments. These chapters take on the way that representations are powerful ways of transmitting cultural knowledge and identity through narrative, the structured stories that are reflective of a particular experiences with general significance, and visual rhetoric, powerfully influential images that can include iconic photojournalism, monuments, lightning-rod events, and the enactment of meaning through the action and movement of bodies. Across these chapters, representation means both how experiences and ideas are translated from one medium into another and how one’s inclusion in the social whole may be registered through such media.