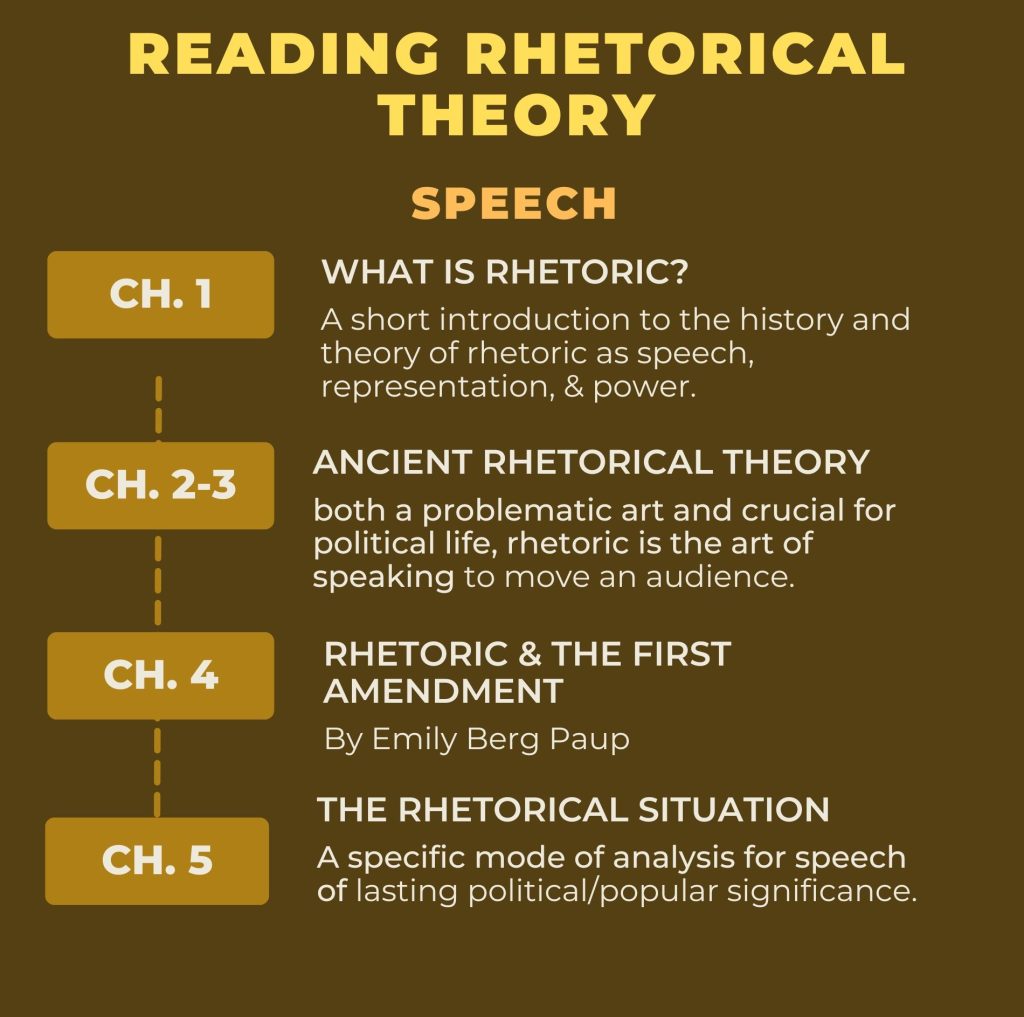

Part 1: Speech

To understand rhetoric as “speech” can mean many things. In most historically distant cases, rhetoric is an art of speech and political oratory; a series of proofs and techniques that prepares the speaker for any possible situation: past, present, or future. Understanding rhetoric as speech can be a way to set it apart from other, related terms, like argument. If arguments refer to the logical form and presentation of claims and evidence, then speeches demand a different rhetorical skill sets like attentiveness to an audience, faculties (abilities) of observation, and adaptability to the particular contexts where speech is called for. Often, students first encounter rhetoric as an art of speaking in their public speaking courses, where rhetorical terms and concepts are aligned with techniques of speaking well on specific topics or under specific circumstances. Such rhetoric can be informative, persuasive, and ceremonial; it can be spoken and written; it can make sense of series of urgent problems in ways that allow audiences to reckon with a difficult set of circumstances.

Why These Chapters?

This book opens with a quick review of what rhetorical theory conventionally is taken to be and covers the three headings that comprise its major units: speech, representation, and power. From there, this unit focuses on the first of these terms: speech. Conventionally, rhetorical theory classes have started with an Ancient Greek context because (1) it is etymological (linguistic) origin of the word ‘rhetoric’ and (2) it is a case study in how and why speech is a powerful political tool when leveraged as a means of persuasion.

Chapter 2 accounts for the Sophists and how their reputations were smeared by Socrates/Plato, while Chapter 3 accounts for philosopher-sophists like Aristotle and Isocrates, whose concerns about rhetoric-as-dangerous persuasion allow us to see parallels with the 20th century U.S. context of dangerous propaganda. There are, of course, problems with starting with this context: Ancient Greece was not as ‘ideal’ of a democracy as has often been taught, the role of speech in it cannot be easily generalized to a contemporary context, and ancient Greek teachers of speech — the Sophists — have a lasting negative reputation because of philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Isocrates, and others. The purpose of starting with Ancient Greece is to draw out these complexities, warts and all.

From there, Chapter 4 by Emily Berg Paup expands on speech as a legally enshrined right codified into law, drawing on Greek terms such as isegoria and parrhesia as the precedent for what we might think of as ‘free’ and ‘fearless’ speech. It accounts for the transformations of speech in a more contemporary context and how we might imagine rhetoric to be a suitable explanatory mechanism not for explaining what speech is in a fixed or forever sense, but how it fluctuates and changes with the times.

Chapter 5, 2hich concludes this unit, is about “the rhetorical situation,” a popular framework employed by many rhetorical scholars for the analysis of speeches and the specific context that informs them. Drawing on distinct elements (exigence, audience, and constraints) the rhetorical situation offers a powerful lens to understand why a speech was delivered when it was delivered, and how this context is essential for understanding rhetoric’s received meanings, then and now.