Chapter 1: What is Rhetorical Theory?

This chapter offers a brief overview and definitions of rhetorical theory. “Theory” is sometimes imagined as abstract thinking or complex philosophy. However, in this class “theory” is something that all people do when they seek to apply a way of thinking about the world to real-life circumstances. It describes the imaginative and practical meanings that are applied to a surrounding world, and how we revise those meanings in accordance with perceived changes to that environment. Rhetorical Theory most often describes our ways of understanding practices of meaning-making and interpretation that rely on persuasion. As explained below, persuasion is traditionally associated with historical practices of speeches and speech-making. This is why Rhetorical Theory is often described as the “art of persuasion” or the “art of speechmaking,” although subsequent chapters will build on (and depart from) this foundation.

Please note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recording

- What is Rhetorical Theory? (Audio, ~12m)

Read this Next

- James, Joy. “Teaching Theory, Talking Community.” Seeking the Beloved Community: A Feminist Race Reader, State University of New York Press, 2013, pp. 3-7.

- Handout: Definitions of Rhetoric

Defining Rhetorical Theory

The two Greek words that combine to form rhetoric are techne, as art or skill, and rhetor, or speaker. The two terms are not explicitly linked in fifth-century Greek texts, and there is no explicit reference to the art of persuasion in the first recorded use of the word. The word rhetor was a legal term denoting a specific class of people: those who often put forward motions in courts of law and in the general assembly.

Perhaps the most widely circulated definition of rhetoric still circulating today is from Aristotle: “the faculty of observing the available means of persuasion, in any given situation.”[1] That means that rhetoric isn’t just how we persuade. It’s also the ability to stand back from the scenes where persuasion happens to understand how and why it is happening. Another popular definition of rhetoric is “the capacity to affect and be affected.” This means that rhetoric becomes the art of movement, or how people use their bodies to create movements and change. Both definitions capture the perspective that we can take when we think rhetorically: one that seeks to understand the way that influence and power move and the role of communication in creating common knowledge.

My preferred definition of rhetoric is “the active and retroactive organization of discourse.” This means that rhetoric is a way of creating a shared perspective on the past and future, a way of organizing speech to correct or realign a point of view. At its most basic, we might think of rhetoric as “the art of speaking” or even “the art of speaking well,” which is part of the reason why public speaking classes are housed in Communication Studies departments. Before Communication Studies existed as an academic discipline, most of these departments were named “Speech Communication,” which reflects rhetoric’s traditional emphasis on the theory, criticism, and practice of speech-making. That’s still a central aspect of the theory that rhetoricians are interested in, although these theories have also grown broader in scope.

In this class, rhetoric, as we understand it today, is a collection of humanist, literary, and political theories that explain how speech motivates human action and imagines possible futures. As developed in this un-textbook, it is a theory of how speech, representation, and power are instruments rooted in understandings of persuasion and its audiences. Persuasion is key to rhetoric because it is both the thing that rhetoricians study and the thing that rhetorical scholarship seeks to generate: the imagining of a more just world.

More important than just defining rhetoric is thinking critically about which definitions of rhetoric that we choose to embrace. Although he is among the earliest people to theorize rhetoric, Aristotle is not always the best authority because we would register many of the views he espoused as philosophy as categorically inhumane or racist.

It is important not only to situate rhetorical theory in the context from which it emerges but also to assess the utility of these theories according to the ethical standards that we would abide by in our own present-day. As the scholar and abolitionist Joy James writes:

Philosophy or theory courses may emphasize logic and memorizing the history of “Western” philosophy rather than the activity of creating philosophies or theorizing. When the logic of propositions is the primary object of study, how one argues becomes more important than for what one argues. The exercise of reason may take place within an illogical context — in which academic canons absurdly claim universal supremacy derived from the hierarchical splintering of humanity into greater and lesser beings, or the European Enlightenment’s deification of scientific rationalism as the truly “valid” approach to “Truth.[2]

In keeping with James’s statement, this class seeks to critically address how rhetorical theory has been made or built. It is not just about memorizing rhetoric’s ancient history. It does not seek to elevate a predominantly white or “Western” tradition as the only one that matters or exists.

One way to think beyond this tradition is what rhetorical theorist Molefi Kete Asante calls “Afrocentricity.” Afrocentricity describes a worldview that is “pro-African and consistent in its beliefs that technology belongs to the world; Afrocentricity is African genius and African values created reconstructed and derived from our history and experiences in our best interests.” Asante argues that Afrocentricity is essential to understanding rhetoric for the following reasons:

“Maulana Karenga argues that “no people can turn its history and humanity over to alien hands and expect social justice and respect” (Karenga, 1979). Language is the essential instrument of social cohesion. Social cohesion is the fundamental clement of liberation. All language is epistemic. Our language provides our understanding of our reality. A revolutionary language must not befuddle; it cannot be allowed to confuse. Critics must actively pursue the clarification of public language when they believe it is designed to whiten the issues. We know through science and rhetoric; they are parallel systems of epistemology. Rhetoric is art and art is as much a way of knowing as science.” [3]

This course is about rhetorical terms and concepts. It is also about why it matters where and when we start rhetoric’s story and why rhetorical criticism is still a useful theory of practice. In this un-textbook, we will return to ancient Greece, but with a specific purpose: to highlight the ways that rhetoric signaled a broken or unhealthy state of public and political affairs. By telling this ancient story in this way, we may also bear witness to how the characteristically unjust patterns and practices of those times live on for us in the present day.

Artistic Proofs and Genres

Let’s talk about some of the most commonly discussed concepts in rhetoric and rhetorical theory: ethos, pathos, and logos, which are also known as the artistic proofs. The phrase “artistic proofs” means that they are the elements of persuasion that originate from the speaker, rather than from inartistic sources, or the data the speaker uses but did not ‘originate,’ ‘invent,’ or ‘create.’ Entire courses on rhetorical theory have been built around these concepts. They correspond to the major premises of Aristotle’s book, the Rhetoric, and form three pillars that much present-day rhetorical theory is built upon.

- Ethos, or the appeal to authority. These are the ethical proofs derived from the moral character of the speaker.

- Pathos, or the appeal to the emotions. The objective of pathos is to put the hearer into a certain frame of mind using what the speaker already knows about their audience.

- Logos, or the appeal to reason, logic, and the word. These are the proofs contained in the speech itself when a real or apparent truth is demonstrated. The two modes of logical proof that Aristotle describes are induction and deduction. Induction refers to “bottom-up” reasoning; deduction refers to principles applied from the “top-down.”

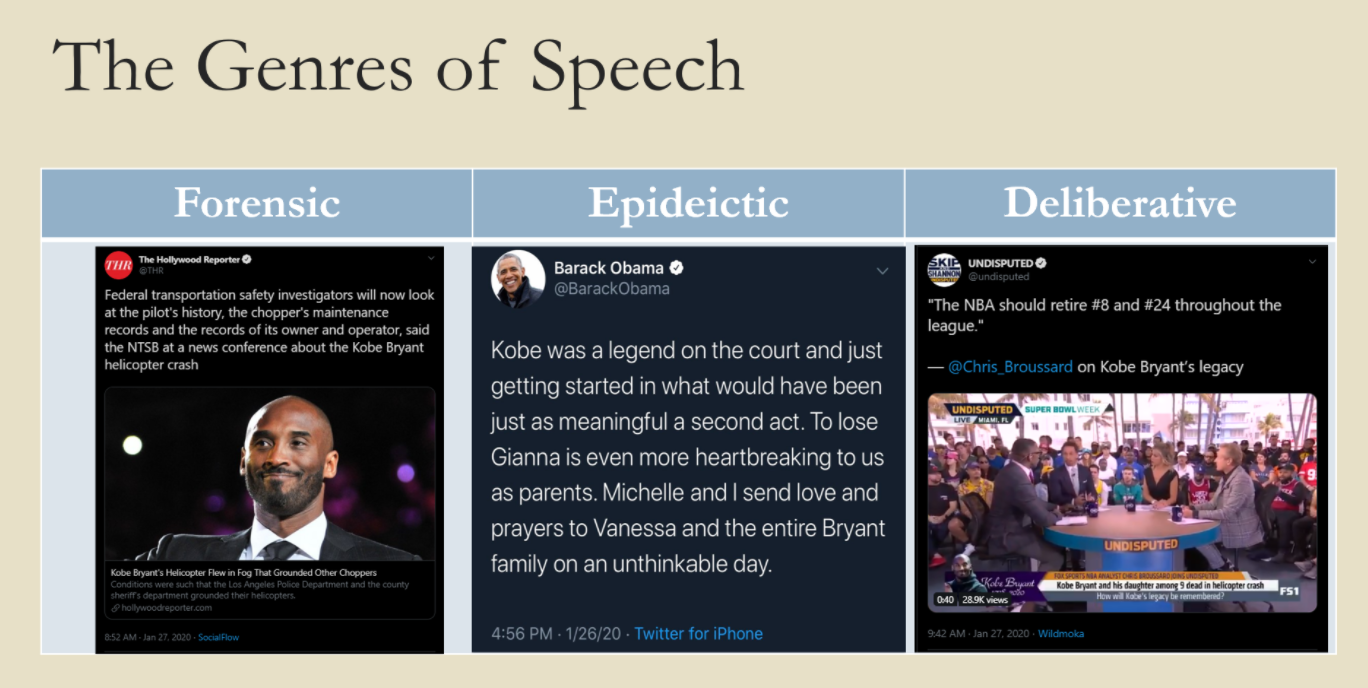

Aristotle’s explanation of logos also describes three genres of rhetoric, which correspond to different “tenses” in which a speech may be made. These include the forensic, the epideictic, and the deliberative. In each of these, rhetoric manages some uncertainty: uncertainty over what is and what is not; uncertainty over whether to praise or to blame; and uncertainty over what one should or should not do.

The Genres of Speech

| Forensic | Epideictic | Deliberative |

|---|---|---|

| The Past | The Present | The Future |

| Facts: whether a thing did or did not happen. | Values: whether to issue praise or blame. | Policy: whether we should or should not take action. |

| Judiciary or the Courts | Punditry or Eulogy | Legislation and Law |

The forensic genre of rhetoric is about matters of fact, what is and is not, what did or did not happen. The forensic corresponds to the past. The site of forensic arguments is typically the judicial system and the courts. Today, the word “forensic” has meaning specifically in a criminal justice context. There, and on “forensic” science television shows, the problem is reconstructing the past, what did or did not happen, who did or did not perpetrate the act.

The epideictic genre of rhetoric is about matters of praise or blame, whether to celebrate or to denounce. It corresponds to the now, the place between past and future. Epideictic speeches are traditionally speeches like eulogies, special-occasion speeches, or toasts; other versions of epideictic could include newspaper opinion-editorials, news-comedy hybrids, or pundit pieces that try to offer ‘spin’ to politicize a person or issue. They can also be speeches, images, and text that highlight a “now” as a particularly urgent or important moment of transition or change.

The deliberative genre of rhetoric is about policy and what should or should not be done. The deliberative corresponds to the future and the course of action that should be taken to attain it. It is traditionally associated with lawmaking and legislature. A speech about the decision to impeach, for instance, is a deliberative one: it is a question of policy and the path that people should pursue.

This rhetorical terminology — ethos, pathos, and logos; forensic, epideictic, and deliberative — is just some of the basic language that is most often associated with the history and discipline of rhetoric. If you take classes in rhetoric elsewhere in the university, you will very likely encounter these foundational terms again.

Histories of Rhetorical Theory

The last thing I want to talk about is the organization of this course and how it relates to the history of rhetoric. Most of the time, rhetorical theory classes start in Classical Greece, where the term was allegedly invented. They might then move through Rome into Western Europe. Many times, such classes end in the 20th century when speech communication departments began appearing in American universities around 1914. Sometimes these courses also cover the 20th century and the developments of structuralist, post-structuralist, and materialist theories. In Communication Studies, this could also include accounts of the functionalist, constructivist, and critical traditions.

This textbook organizes a range of traditions of rhetoric under three headings: speech, representation, and power. Each of these headings captures a wide array of rhetorical theories and span from the ancient to the contemporary. These headings are imperfect at best, given that there is considerable room for overlap. The chapters on the ancient Greek context, ongoing legal battles over the first amendment in the United States, the rhetorical situation, publics, and counterpublics all attest to the role of speech in shaping, exercising, and channeling power. Settler colonial rhetorics are often enmeshed with problems related to representation such as symbols and narrative. Even if they are imperfect, these categories are intended to offer some concrete coordinates for how we may locate rhetoric in a general sense given how difficult it can be to define.

- Speech. One of rhetoric’s earliest and most enduring associations is as a theory of speech, which tends to feature problems related to persuasion, contingency (i.e., uncertainty), and adaptability to a specific situation. Early chapters are devoted to the so-called “origins” of rhetorical theory, its deeply troubling beginnings, and the idea of the “common good.” We start here because this history helps us to define rhetoric and illustrates how problems within a rhetorical culture illuminate similar problems that resonate with us in the early 21st century. It then moves to more contemporary frameworks that similarly center rhetoric’s role as an art of speech, persuasion, and world making with chapters on rhetoric and the first amendment and the rhetorical situation, an evolving framework for studying speech within and across distinct moments in time.

- Representation. When rhetorical theories are associated with representation, they tend to feature problems related to the interpretation of signs, symbols, and arguments as well as the unique tools associated with crafting and deciphering messages in written, visual, and narrative forms. This part of the book also offers chapters on the public sphere and counterpublics, both of which grapple with the problem of representation in terms of audience: who is ‘the’ public, and what other kinds of publics might it be defined against?

- Power. When rhetorical theories are associated with power, they tend to feature problems related to the complex interaction among ideology, institutions, identities, histories, and technologies in the creation of unequal social hierarchies and strategies for dismantling structures that uphold inequitable force relations among different groups. In this final part of the book, chapters offer detailed accounts of how rhetoric is related to ideology, how we may redefine rhetoric’s core tenets around the culture, identity, and traditions of Latine rhetorical theory, the enduring and transforming legacies of settler-colonialism, the way that secrets and surveillance make use of rhetoric to keep different publics distracted or in compliance, and how digital rhetorics preserve and transform ancient ways of thinking about the spoken arts.

Speech, words, and language have consistent and long-lasting effects. Rhetorical theory can describe the ability of a speaker to invent persuasion, envision and steer their audience, and change the real-world scenes where rhetoric is received or taken up. Rhetorical theory is also a way of understanding the process of public meaning-making, or how representations can take on a vital life of their own. Finally, rhetorical theory can be a tool for ethical world-making, one that allows us to make more deliberate and inclusive choices about our speech.

Additional Resources

- Ira Allen, “Presentation and Rhetorical Theory” and “Fantasies of Rhetorical Theory“

- James, Joy. “Teaching Theory, Talking Community.” Seeking the Beloved Community: A Feminist Race Reader, State University of New York Press, 2013, pp. 3-7.

- Handout: Definitions of Rhetoric