Chapter 9: The Public Sphere

The Public Sphere, Symbolic Action, and Civic Engagement

Angela M. McGowan-Kirsch

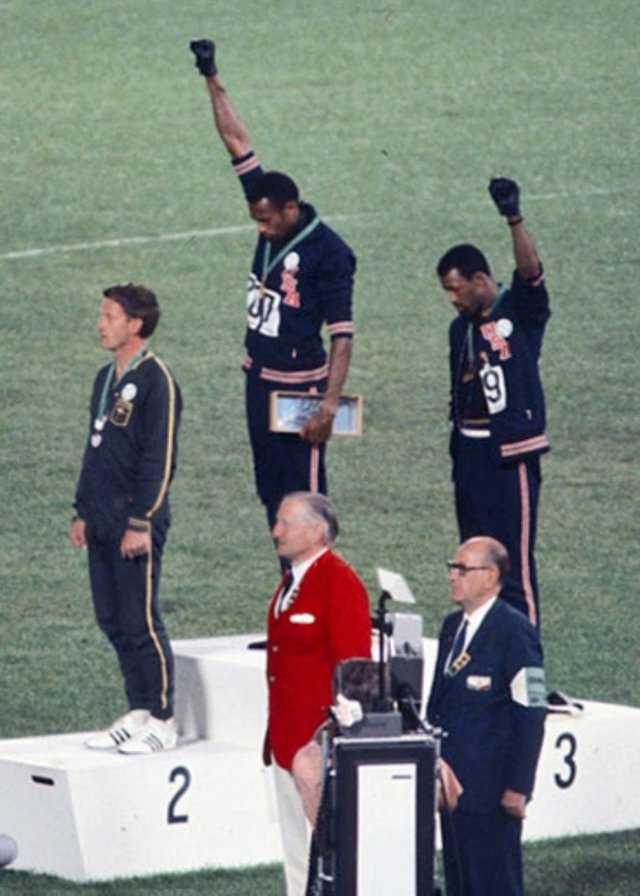

Rhetorical critics who study rhetoric create new knowledge regarding what makes communication (rhetoric) effective. When analyzing a rhetorical act, critics will often examine its symbols. From Chapter 4, a symbol is an image, sound, or word representing something else. A symbol can convey meaning and vary depending on cultural context. A rhetorical critic studying the picture above may be interested in why and how a particular symbol—the clenched fist—was successful or unsuccessful in urging an audience to think, feel, believe, or do something. The symbol in the picture is not a mere image but a powerful communication tool, sparking curiosity and inviting deeper analysis.

When humans use symbols, they engage in symbolic action, which refers to using symbols to express meaning or communicate ideas, often through behavior or ritual. Symbolic actions are deliberate and are intended to convey messages, express beliefs, or bring about social change. For instance, a public demonstration—such as the one shown above—may involve symbolic actions like holding signs, chanting slogans, or performing symbolic gestures to express a collective message. Symbolic action becomes a useful rhetorical device because it is a powerful tool for identity formation, social reality construction, social movement mobilization, and cultural expression.

Let’s use another example to explore the distinction between symbols and symbolic action. I teach at a university near Buffalo, NY. In 2022, there was a mass shooting at a local supermarket in Buffalo. When a tragic event like this one occurs, people often lay wreaths and flowers at the memorial site as a sign of respect and remembrance. This is an action that is performed symbolically or ceremonially.

In the photograph below, you’ll see a variety of flowers. Before visiting a memorial site, a person will choose a particular flower color to represent what a deceased person means to them. For instance, a white flower symbolizes innocence, purity, and honor. People may place a white flower at a memorial site to express love, respect, and grief. The flower is a symbol, and putting it at the memorial site makes it a form of symbolic action. In doing so, the flower becomes a powerful symbol of sentiment and serves to honor the killed people, express grief, and show support for a cause. While a symbol (flower) is a tangible representation of an abstract concept, symbolic action involves the intentional use of the symbol (flower) in behavior or rituals (placing it at a memorial site) to convey meaning or communicate an idea.

We uncover a symbol’s rhetorical consequences by understanding what a rhetorical action means and what it does. Remember, a symbol is an arbitrary representation of something else (a white flower at a funeral symbolizes love for one person and grief for another). Symbolic action occurs when people use that symbol (a white flower) to engage in action (placing it as a memorial site to achieve an outcome). Studying symbolic action helps rhetorical critics better understand how humans use symbols to affect the world. Moreover, while studying rhetoric, symbols, and symbolic action, we get a sense of rhetorical agency, which refers to our capacity to act in a way that gets others in our community to mobilize. This is where civic engagement enters. Change and maintenance of social, political, and economic structures is accomplished through civic engagement, and civic engagement is achieved through rhetoric. People use rhetoric to develop their identity as individuals and citizens and determine what should be done about a problem.

This chapter explores rhetoric and symbolic action in the context of civic engagement. Civic engagement is “a multifaceted concept, consisting of political interest, political discussion, and political knowledge” (Mossberger et al., 2008, p. 48). Accordingly, civic engagement activities tend to focus on political involvement, which involves actions related to systems’ efforts on individuals and communities. Civic engagement encompasses individuals’ activities to participate in their communities and broader society. It is critical in fostering active citizenship, building stronger communities, and advancing social justice and democracy. Consequently, studying symbolic action in the context of civic engagement offers beneficial insights and tools for promoting effective communication, mobilizing collective action, fostering social cohesion, and advancing social justice and inclusion. To this end, the chapter is broken up into two parts. In Part 1, I apply various concepts related to rhetoric and symbolic action to 5 examples:

- Example 1: A hot dog

- Example 2: Bell “Let’s Talk” campaign

- Example 3: #NotOneMoreDisplay

- Example 4: Disability Nation art

- Example 5: A reshaping of the American flag

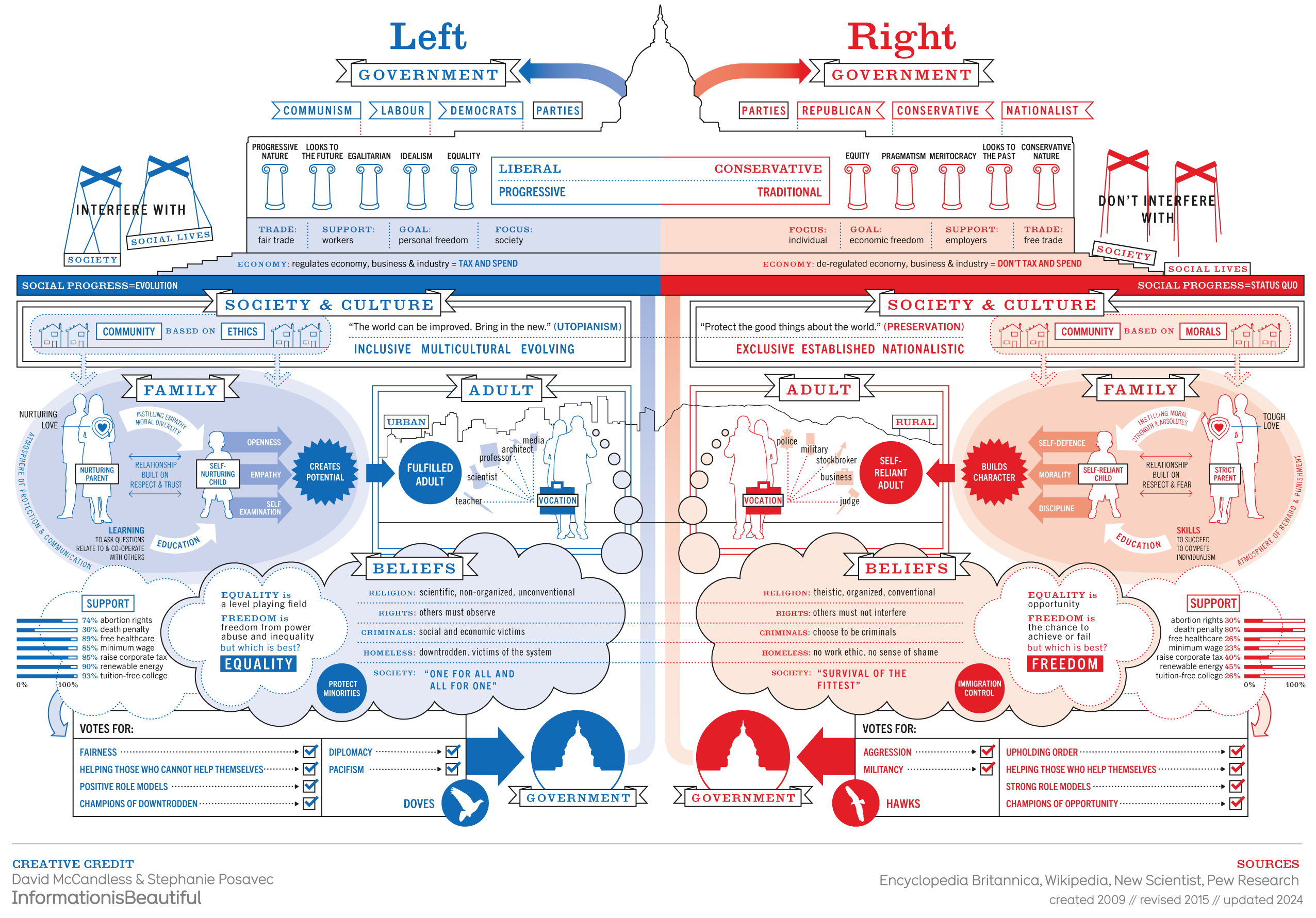

This section concludes with an activity on the Left-Right Political Spectrum and a discussion of political polarization. Then, I discuss rhetoric and civic engagement in the public sphere. Within this section, I discuss two types of civic engagement: activism and political engagement. The chapter ends with a summative conclusion. Throughout the chapter, you’ll find hyperlinks to websites and videos that provide additional information on concepts.

Part 1: Rhetoric and Symbolic Action

Kenneth Burke (1969) considers symbols as action, hence the phrase “symbolic action.” Rhetoric is not just a communication tool but a powerful mode of symbolic action, which is the “constitution of social reality through symbols that foster identification” (Hallsby, 2022). Rhetoric is how symbols act in our world (Palczewski et al., 2022). Burke (1969) considers humans to be “symbol-using animals” such that when we use symbols, we engage in symbolic action. A rhetor refers to “any person, group, or institution that uses symbolic action” (Palczewski et al., 2022, p. 5). Understanding rhetoric as a mode of symbolic action can enlighten us about the profound influence of symbols in shaping our social reality. You can learn more about symbolic action and Burke’s concept explanation in Chapter 4.

Example 1: Rhetoric as Symbolic Action: A Hot Dog

On June 11, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt hosted King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at Hyde Park, their home in Hudson Valley. It was the first time a reigning British monarch had set foot in its former colony. The president served the royals a dinner of hot dogs and beer to celebrate. The Queen had no idea how to eat the hotdog. The casual American-style picnic was meant to dispel anti-British sentiment. The president hoped the picnic would humanize the British monarch and win the American people’s sympathy. The following day, the picnic made the front page of the New York Times with the headline, “KING TRIES HOTDOG AND ASKS FOR MORE.” The photo below captures Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt and Queen Elizabeth leaving the station for the White House.

In this example, the hotdog became more than food—the hot dog was a symbol that fostered a “likable” impression of King George VI of Great Britain. As a symbol, the hotdog’s meaning was fluid because it held a different meaning for different people. While the literal meaning of a hot dog is “a sandwich consisting of a frankfurter in a split roll, usually eaten with mustard, sauerkraut, or relish” (Dictionary.com, 2024), some could say it represents summer, hosting cookouts with family and friends, and baseball. Michaels (2020) commented, “The simplicity of the event endeared the King and Queen to the American public who now saw them as regular people capable of casual dining rather than as evil colonial rulers” (para. 5). Thus, the hot dog became a symbol that contributed to the president’s construction of Americans’ social reality. Who knew that a hotdog—and what it symbolized—could play a key role in diplomacy?

This video features a montage of President Roosevelt meeting the King of England shortly before World War II.

Example 2: Rhetoric as Symbolic Action: Bell “Let’s Talk” Campaign

The photo above shows the Bell Let’s Talk logo. The logo represents (or symbolizes) the meaning behind the day: end the stigma around mental health and start a conversation to initiate change surrounding the topic. The flag may look familiar if you are Canadian because the awareness campaign is prominent in your country. However, those outside Canada may have never seen the logo or heard of the “Bell Let’s Talk” campaign. Consequently, the symbol might have little meaning for some and great significance for others, particularly those who have mental health issues. You’ll see examples of visual symbols in a 2024 “Bell Let’s Talk” advertisement. This commercial also provides more information on creating change in mental health.

Although symbols like the “Bell Let’s Talk” logo often represent tangible things, they also exemplify a constructed reality. Kornfield (2021) defines constructed realities as “The ways of life that humans take for granted as the natural order, even though humans originally constructed them through symbols” (p. 5). This aligns with concepts discussed in Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, which emphasizes that reality is not something we passively observe but actively shape through interactions and shared meanings. Symbols are central to this process, influencing our perceptions, behaviors, and attitudes. For instance, a symbol gains its meaning through social processes. When encountering symbols, we draw on cultural backgrounds, personal experiences, and social contexts to ascribe meaning. This meaning, in turn, shapes how we perceive ourselves, others, and the world, thus constructing our social reality.

Example 3: Rhetoric as Symbolic Action: #NotOneMore Display

In an act of protest on March 13, 2018, activists placed 7,000 pairs of shoes outside the U.S. Capitol building. Each pair symbolizes a child who was killed by gun violence since Sandy Hook (Icsman, 2018). From 8:30 am to 2:00 pm, the shoes were displayed on the southeast lawn in the hope of sending a clear message to Congress: Reform gun control legislation or more children will be killed by gun violence. A global advocacy group, Avaaz, planned the protest and collected shoes from people from across the country (Icsman, 2018).

The shoes, which covered 10,000 square feet, became a form of symbolic action. The symbol—pairs of shoes—became an arbitrary representation of something else: the estimated number of children who die from gun violence every year. By capturing media attention and eliciting emotional responses, activists’ symbolic actions framed a social issue, sought to shape public opinion, and influenced policy debates.

This is also an example of how a rhetor may use visual symbols to represent a thing, concept, or action. As such, the installation advocated for gun control legislation while fostering a sense of collective responsibility and urgency for change. In this instance, Avaaz’s use of symbols sought to spark cooperation, generate identification, produce division, enable persuasion, and constitute identity. Identity is rhetorically constructed and refers to the “physical and behavioral attributes that make a person recognizable as a member of a group” (Palczewski et al., 2022, p. 193). By participating in the protest, those who donated shoes advanced a uniform identity that answered the question, “Who/what are you.” This further exemplifies how symbolic action can contribute to constructing identity within a person’s social reality. By engaging in this symbolic action, people participating in Avaaz’s act of protest asserted their identities, values, and beliefs, thus shaping how others and themselves perceived them.

Example 4: Rhetoric as Symbolic Action: Disability Nation

When you look at “Disability Nation,” what verbal and visual symbols do you see? How does the rhetor’s social reality appear within the mixed-media artwork? The rhetorical act contains visual and verbal symbols. As you examine its persuasive message, remember that when people engage in symbolic action, they construct social reality. After all, symbolic action creates the meaning people ascribe to the things in their world.

While in her 40s, the rhetor, Cheryl Kinderknecht, was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a rare eye disease that causes vision loss. Kinderknecht did not want her loss of vision to impede her identity as an artist. Guided by her social reality, Kinderknecht created this rhetorical act in response to H.R.620: ADA Education and Reform Act of 2017. Many disability advocates believed that despite being disguised as strengthening the Americans with Disabilities Act, the ADA Reform Act weakened the Americans with Disabilities Act while also undermining the key goals of the law (ACLU, 2017). This video features Cherly Kinderknecht discussing the Art of Possibilities Art Show. In the video, the mixed-media artist discusses her piece, In the Garden with Friends, and how her visual impairment influences her art.

“Disability Nation” is a form of protest art in which Kinderknecht uses symbolic action—words, images, and artifacts—to construct, maintain, and transform others’ social realities. The rhetor challenges prevailing social norms and structures by addressing injustices and disrupting established social norms and hierarchies. This rhetorical act prompts the audience—such as yourself—to discuss what the rhetor believes is a pressing societal problem and mobilize individuals around a common goal.

Furthermore, “Disability Nation” features symbols that depict an ideology. In Chapter 6, ideology is defined as “the religious, artistic, moral, and philosophical beliefs contained within and perpetuated by a society or culture, and which are determined by the material circumstances that occasion them” (para. 5). In the case of “Disability Nation,” ableism is an apparent ideology. Ableism is the discrimination of and prejudice against people with disabilities. This ideology is grounded in the belief that people with “normal” abilities are superior. Similar to sexism or racism, ableism classifies people as “less than.” This BuzzFeed video explores ableism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_b7k6pEnyQ4

Ideology is a comprehensive set of normative beliefs that an individual, group, or society possesses. Ideology reinforced signs and symbols. For instance, in “Disability Nation,” the American flag is hung upside down. A hegemonic reading of the American flag proposes that the American flag is a national symbol of freedom and democracy. Yet, when people fly an American flag upside down, it is generally seen as a symbol of a distressed nation. The symbol represents an abstract ideological concept, value, or belief in this example.

The rhetorical act incorporates symbols that contest and resist dominant ideologies (e.g., ableism) by challenging their meaning, power structures, and narratives. In doing so, the rhetor appropriates existing symbols (e.g., the wheelchair) and creates new ones to subvert dominant ideologies. Kinderknecht challenges hegemonic ideologies and advocates for social change by reinterpreting or reclaiming symbols. As a result, the rhetor elucidates alternative values and viewpoints.

Example 5: Rhetoric as Symbolic Action: A Reshaping of the American Flag

The flag of the United States— “Old Glory”—is a symbol deeply embedded within American cultural practices and traditions. The American flag is encoded with ideological meanings (e.g., democracy) and values (e.g., freedom) in everyday life. For instance, by reciting the “Pledge of Allegiance” in elementary school, the American flag became integrated into our cultural practices; thus, we internalized the ideology tied to the flag. This, in turn, shaped our perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors as Americans.

Let’s discuss a different iteration of “Old Glory”— the “Blue Lives Matter” flag, which features a modified American flag with one blue stripe. Although the traditional American flag symbolizes unity, the “Blue Lives Matter” banner sparks disagreement between those who favor defunding law enforcement agencies and those who believe it symbolizes honor and sacrifice. The banner, which represents the police, is associated with the Blue Lives Matter movement, a countermovement to the Black Lives Matter movement. In addition to representing solidarity with police, the banner is a response to and rejection of the Black Lives Matter movement (Kweku, 2024). Its flag functions as a symbolic action by incorporating symbolic elements to support law enforcement, raise awareness of related issues, mobilize political action, and respond to broader social and political contexts. As a symbol, the “Blue Lives Matter” flag holds cultural significance and serves as a rallying point for individuals and groups advocating for police officers’ interests.

The “Blue Lives Matter” banner’s meaning has a much more specific ideology than the United States flag. Although the thin blue line was originally meant to symbolize the uniform color worn by police officers, the thin blue line has “become emblematic of white nationalist, neo-Nazi, and alt-right movements in the U.S.” (Thin blue line, 2024). Many rioters carried this banner while storming the capitol on January 6, 2021 (Kweku, 2024). Thus, the thin blue line banner moves from the level of a symbol charged by and deployed in service of ideology to that of symbolic action. This occurs, for instance, when politicians use the rhetorical act for political gain. By rallying support around the flag, advocates seek to mobilize political action, influence policy decisions, and shape public discourse on police funding, training, or accountability.

As another example, at a rally in 2020, candidate Donald Trump made a closing argument that featured the thin blue line banner. The Trump campaign cast the Democrats as enemies of law and order and, in turn, law enforcement (Kweku, 2024). Then, Trump and his supporters at the Republican National Convention claimed, “Under President Trump, we will always stand with those who stand on the thin blue line” (Kweku, 2024). This demonstrates how the “Blue Lives Matter” flag can be understood as a response to broader social and political contexts. Symbolic actions, such as adopting the flag, reflect efforts to counter criticisms of law enforcement and assert alternative narratives that prioritize the perceived needs and challenges facing police officers.

The “Blue Lives Matter” flag is associated with political movements (e.g., the Blue Lives Matter movement) and political campaigns (e.g., President Trump). Given this, the blue line flag provides an entry point for discussing ideologies: conservatism and liberalism. Political parties—such as Republicans and Democrats—have ideological affiliations that differentiate them from one another. For instance, those belonging to the Democratic Party may possess a liberal ideology, whereas members of the Republican Party support a conservative ideology. People often use the left-right political spectrum to describe a political ideology.

Activity: Symbols and the Left/Right Political Spectrum.

Before continuing, visit polarizationlab.com to learn where you fall on the ideological spectrum. Once you discover your score, consider how your political ideology shapes your social reality. Then, contemplate how your social reality can lead to political polarization.

As political polarization increases in the United States, so does the tendency for Republicans and Democrats to view those who identify as members of the opposing party negatively and people of the same party more positively (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015). In a polarized electorate, people do not hold centrist attitudes but push toward ideological extremes. As polarization increases, the center begins to disappear (Levendusky, 2009). Evidence indicates that supporters of political parties loathe and distrust people from the opposing party (Druckman & Levendusky, 2019; Iyengar et al., 2019). For instance, Moore-Berg et al. (2020) found that Democrats and Republicans exhibit a steady and persistent bias in how much prejudice and dehumanization they express toward people who hold a different party affiliation. Because perceptions of polarization influence behavior (Van Boven et al., 2012), we should reflect on our perceptions of people from the opposing party and how/why these perceptions came into existence. Why does aligning yourself with one side lead to hostility toward members of the contrasting party?

Let’s do a quick activity:

- Complete the “Ideology Checker” quiz, which is available at https://www.polarizationlab.com/ideologyquiz.

- After reviewing your results, consider how your experiences and perceptions influenced your chosen statement.

- I challenge you to engage in a political discussion with people who deviate from your party affiliation and ideological beliefs. Why? Research suggests that political discussions with those with different political views and support of a political party that diverges from one’s own have positive implications for democracy (Nir, 2017).

I would be remiss if I did not point out that there are instances when points of view are not equally valid (e.g., xenophobic, homophobic, or racist attacks; hate speech; misinformation; white supremacist and alt-right trolling). Serving to divert attention, these communicative acts do not warrant a response. To summarize, a rhetor is any person, group, or institution that uses symbolic action. Symbolic action, which is expressive human action, uses symbols to persuade. These symbols provide an arbitrary representation of something else. A symbol represents a word, image, or artifact representing a thing, thought, or action. Now, let’s discuss symbolic action as it relates to civic engagement.

Part 2: Rhetoric and Civic Engagement in the Public Sphere

Civic Engagement

Civic engagement is “people’s participation in individual or collective action to construct identity and develop solutions” (Palczewski et al., 2022, p. 14) to problems facing one’s community and beyond. Civic engagement is also “a multifaceted concept, consisting of political interest, political discussion, and political knowledge” (Mossberger et al., 2008, p. 48). Civic engagement motivates civic participation because the individual’s interest in politics and current events can translate into action (Klofstad, 2011). Accordingly, civic engagement activities tend to focus on political involvement with actions related to the effects of systems on individuals and communities. Before continuing, let’s explore your connection to civic engagement by answering these questions:

- A civic association is an organization whose official goal is to improve neighborhoods through volunteer work by its members. What civic organizations do you belong to?

- How do you enact citizenship and civic engagement? Remember, civic engagement as a process is a “mode of public engagement.” Participation in society has many different forms, all of which involve symbolic action

- How do you use rhetoric to persuade and/or seek recognition from others to support the organization? When you engage in rhetoric, you necessarily commit yourself to an interaction.

On the Illinois State University’s Center for Civic Engagement’s webpage, readers find an infographic identifying different civic engagement forms. In this chapter, we focus on political engagement and activism. While activism “involves organizing to bring about change or show support” for a particular cause or policy,” political engagement “develops one’s political understandings and views that may be expressed by challenging the political ideas of others and/or influencing politics or political positions” (Center for Civic Engagement, 2024).

The Public Sphere

In both contexts, citizens discuss social issues in the public sphere. Jürgen Habermas identifies and describes the public sphere in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Habermas (1992) defines the public sphere as “a network for communicating information and points of view” (p.x), which converts into public opinion. Habermas’s public sphere refers to a space within a society where individuals engage in rational discourse, debate, and deliberation about matters of common concern. Consequently, political engagement, which involves individuals participating in activities to influence or shape political processes and decisions, intersects with Habermas’s notion of the public sphere.

Habermas believes there is a space and time for deliberation in a true public sphere. Habermas (1991) proposes that the public sphere is a place where people can join to discuss and identify societal problems freely. Debate within the public sphere enables discussants to have open access, a place to bracket social inequalities, have rational discussions, and focus on common issues (DeLuca & Peeples, 2006). After debate ensues, the public is described as the carrier of public opinion, and “its function as a critical judge is precisely what makes the public character of proceedings meaningful” (Habermas, 1991, p. 2). Habermas emphasizes the importance of deliberative democracy within the public sphere, where citizens engage in reasoned dialogue and debate to reach informed collective decisions. Political engagement that fosters deliberation, such as town hall meetings, citizen assemblies, or participatory forums, contributes to the democratic process by enabling citizens to participate actively in decision-making and policy formation. This, in turn, creates a public sphere that provides an inclusive and accessible space where individuals from diverse backgrounds can participate in political discourse and decision-making. Political engagement initiatives promoting inclusivity help ensure marginalized voices are heard and represented within the public sphere.

Historically, public discussions about others’ use of political power grew out of eighteenth-century bourgeois society (Habermas, 1974, 1991). Habermas (1974) understood the bourgeois public sphere to be “the sphere of private individuals assembled into a public body” (p. 54). The bourgeois public sphere coincides with the social welfare state of mass democracy (Dahlgren, 1995). Within the public sphere, public opinion mediates between society and a country’s leaders, and public opinion affirms and guides the affairs of the state. Before continuing, read this summary and watch this video discussing Habermas’s book, The Structural Transition of the Public Sphere.

The public sphere emerged in the 18th century along with the growth of coffee houses, voluntary associations, and the press (Habermas, 1991). Habermas (1991) suggests that when people gather in these public places, they express their thoughts in the public sphere. Essentially, the public sphere signifies a social space where people assemble to express and form public opinion (DeLuca & Peeples, 2006). In the public sphere, citizens congregate to converse about society and debate issues. Thus, Habermas’s public sphere is characterized by rational-critical debate (Breese, 2011). Habermas (1991) clarifies that events and occasions happening in the public are “open to all, in contrast to closed or exclusive affairs” (p. 1). While congregating in the public sphere, citizens use communication to transmit information and influence those who receive it (Habermas, 1974). The major discourses found in Habermas’s model are means for the virtual representation of direct discourse. In addition to coffee houses and voluntary associations, the press also played a role in the emergence of the public sphere. This video features rare footage of Habermas discussing some of his theories.

The public sphere has taken on a new form in that it attracts public opinion because of the free press (Habermas, 1991). Habermas (1991) describes the significance of the press as “developing a unique explosive power” (p. 21). Habermas (1974) identifies newspapers, magazines, radio, and television as comprising the public sphere, for these are mediums in which people can express their ideas, share opinions, and disseminate the news. Even in the eighteenth century, newspapers were described as influencing party politics because those publishing the news were seen as leaders of public opinion (Habermas, 1974). Despite the public sphere being described as a place for open discussion, some marginalized groups have not been allowed to participate in the public sphere (e.g., discussions in Calhoun, 1992).

The power of the public sphere resides in communication acts such as debate and discussion. The political public sphere is a space where citizens can access dialogue that addresses questions of common concern (Dahlgren, 1995). It is during these discussions that public opinion can be formed (Habermas, 1991). Habermas envisions a public sphere that surfaces each time “private individuals assemble to form a public body” (1974, p. 248). During this time, citizens discuss issues, with the mass media becoming a chief institution of the public sphere (Dahlgren, 1995). Habermas (1991) contends that mass media, such as television and advertisements, erodes the critical function of the public sphere, which was initially “made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society” (p. 176). Habermas argues that the mass media has caused the public sphere to lose exclusivity because less educated citizens have entered the scene (Dahlgren, 1995).

Dahlgren (1995) points out that the utility of the public sphere is valid and helpful because “it points to those institutional constellations of the media and other for fora information and opinion” (p. 9). This public sphere scholar also believes communication action is necessary for the public sphere. Communicative action depends “on situational contexts, which in turn represent segments of the lifeworld of the participants in interactions” (Habermas, 1998, p. 111). According to Habermas, speakers are constantly advancing claims about the validity of their statements (Dahlgren, 1995). Like his description of the public sphere, Habermas suggests that communicative action involves people coming together to discuss and respond to particular societal crises. This coincides with the notion of the political public sphere. Habermas’s view of the public sphere is the most fruitful (Dahlgren, 1995) despite its critics (DeLuca & Peeples, 2006; Fraser, 1992). As Fraser (1992) notes, “… the public sphere is indispensable to critical social theory and democratic political practice” (p. 247).

Scholars have criticized Habermas’s focus on a single public within the sphere (e.g., discussions in Calhoun, 1992). For instance, Fraser (1992) argues that feminist scholars should move beyond Habermas’s original claims and focus on multiple unequal publics. Following suit, scholars acknowledge that Habermas’s selection of the term “public” had exclusionary political implications that led to the suppression of women and minorities (Hauser, 1998). Hauser (1998) also critiques Habermas’s ideal rational communication model while creating his “reticulate public sphere.” Other critics, such as Deluca and Peeples (2002), contend that political discourse exists in a televisual public sphere instead of a public sphere. Amidst the criticism, Habermas (1991) acknowledges that he would have revised his original text. Shortly thereafter, he discusses the media’s role in promoting civic participation (Habermas, 1992). Despite its limitations, Habermas’s notion of the public sphere remains useful (Dahlgren, 1995). If you want to learn more about Habermas’s idea of the public sphere, check out this video:

In summary, political engagement and Habermas’s understanding of the public sphere are interconnected, as both involve citizens actively participating in public discourse, deliberation, and decision-making processes about matters of common concern. By fostering democratic dialogue, accountability, inclusivity, and civic participation, political engagement contributes to the vitality and effectiveness of the public sphere.

Civic Engagement in the Public Sphere: Activist Movements

Now that you have a sense of civic engagement in the public sphere let’s consider activism to be a type that operates within the context of social movements. Activism is a prominent form of civic engagement within the public sphere, characterized by individuals or groups actively advocating for social or political change. In this section, we will focus on protest movements. Protest movements involve collective action to address specific grievances, injustices, or social issues.

Social movements are “struggles on behalf of a cause by groups whose core organizations, modes of action, and/or guiding ideas are not fully legitimate by the larger society” (Simons, 1970). Social movements must choose between violent and nonviolent activities, legal and illegal ones, disruption and persuasion, extremism and moderation, reform and revolution. Stewart et al. (2012) propose a variety of characteristics of social movements, including

- being conscious, organized, and lasting longer than a single protest;

- being composed mainly of ordinary people;

- protesting against something;

- organized;

- existing until it achieves its goal or is terminated and

- emerging unexpectedly.

Social movements are also described as critical actors in traditional politics occurring within the public sphere (Rauch, 2007) and are institutionalized collectives that maintain outsider status. While some scholars, such as sociologists, study movement from an organizational perspective, others examine activists’ rhetoric attempting to produce social change (DeLuca, 1999). Social movements occur when a redefinition of reality is constructed and filtered through rhetoric. Given our focus on symbolic action and civic engagement, I propose that the study of social movements is an account of the social consciousness of society.

Activists may disseminate their messages through speeches, pamphlets, and mass media. Sillars (1980) proposes that a critic should focus time on exploring these message forms. As rhetorical critics, we should remember to focus on messages in all shapes and forms. Even Sillars’ definition of “movement” is critic-focused. The scholar proposes that a critic be cognizant of problems that limit a social movement theory’s usefulness. Of the four issues, I found the problem “assume that movements are linear” most notable. I selected this specific problem because I found Sillars’ statement that writers see linearity as part of the criticism of movement enlightening. He suggests that critics look for characteristics of the movement that define its rhetorical nature. Taking such action should enable me to perceive what is rhetorically significant about the event. Furthermore, Sillars advocates that a movement is “some combination of events occurring over time, which can be linked in such a way that the critic can make a case for treating them as a single unit” (p. 19).

Social movements devote significant portions of their persuasive efforts toward transforming perceptions of the present. This is where symbolic action enters. Remember, when humans use symbols, we are engaged in symbolic action. Symbols construct our versions of reality; as humans, symbols help us understand that reality. This idea is exemplified in the photo below. The Black Lives Matter movement seeks to “eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes” (Black Lives Matter, 2024). An ideology manifests itself rhetorically through the ideas, values, beliefs, and understanding that Black Lives Matter activists have when they see a clenched fist. Consequently, activists in the photo use the clenched fist—a symbol—to depict the social movement’s ideological consciousness.

McGee (1980) and Cathcart (1978) state that social movements appear in public discourse. Social movement’s frames and strategies are affected by ideological positions and network connections to other social movements. As such, another social force at work during a social movement is an ideograph. As was stated earlier in the chapter, ideographs “do the work of ideology” (Enck-Wanzer, 2012, p. 4). People involved in a social movement will search for words to communicate the urgency of a problem and the need to take action. The ability to ascribe relevance to listeners’ lives is necessary to transform perceptions of the present. For instance, a social movement may use symbolic action, such as an ideograph, in its slogan, songs, images, or an image event.

Symbolic action may also be present as social movements engage in storytelling. Let’s revisit our discussion of social reality. You may recall that our “reality is a social product arising from interaction, and communication extends or limits realities” (Stewart et al., 2012, p. 141). Our culture’s symbol system and our interactions shape our reality. As humans, our ability to create, manipulate, and use symbols is what makes us unique from other animals. Since virtually all human action is symbolic and the by-product of symbols, it makes sense that the meaning arising from a symbol results from interaction in specific contexts. As was discussed in Chapter 8, narratives can be a powerful means of altering perception in the present. For example, how do the Black Lives Matter activists in the photo above use storytelling to shape the audience’s social reality?

Social movements often expose a hegemonic viewpoint that molds a culture’s social reality as false and argues that something must be done to alter that reality. A protestor, for instance, will urge people to see their environment as one that needs change. When people recognize a deficiency, they join a social movement to convince others that their situation is intolerable and warrants change (Stewart et al., 2022). While altering the social reality, people will use symbolic action to promote shared meanings, perceptions, and mobilization within a social movement. The rhetoric of speeches, leaflets, pamphlets, newsletters, and social media posts may be replaced by pickets, strikes, protests, sit-ins, and image events. Social symbols, such as gestures, acts, signs, words, and signals, can stimulate action among people within a social movement or be used to recruit others to join the movement. For instance, the clenched fist symbolized power, independence, pride, and self-determination during the civil rights era. Within a social movement, symbols, such as a clenched fist, possess a standard meaning and are a persuasive tool for expressing a thought or belief. Vox produced this video telling the story behind the iconic silent protest at the Olympics.

As with most forms of civic engagement, people can choose whether they want to participate in a social movement. Contemplating the logic of collective action, Mancur Olson (1965) attached the common assumption at the heart of group theory about the natural inclination of citizens to join action in their collective interests. People who benefit from a social movement may not protest but rather “free ride” on others’ efforts (p. 53). Olson (1965) thought these people were rational – they would be “free riders” on the efforts of others. He believed that to attract participants, movements must provide “selective incentives” only to those who participate. Rational, self-interested individuals will not act to achieve common or group interests. Even if all of the individuals in a large group are rational and self-interested and would gain if, as a group, they acted to achieve their common interest or objective, they will still not voluntarily act to achieve that common or group interest.

When it comes to joining a social movement, social networks are seen as a precondition for the emergence of a movement and an explanation for who is recruited. For instance, collective identity is a concept used to get at the mental worlds of participants that might help explain participation: to devote time and effort to protest. People must usually feel excited to be part of a larger group they think they can help. Now, remember Olson (1965) argues that a rational person will not join a social movement and instead “free ride” on others’ efforts. Remember, activism as a form of civic engagement depends on ideological and social commitments from members. As shown in the video below, Sam Peltzman at the Challey Institute discussed the legacy of Mancur Olson’s groundbreaking book.

In summary, activism encompasses diverse civic engagement practices within the public sphere, each aimed at challenging injustices, advocating for change, and promoting social or political transformation. Social movements employ various strategies, tactics, and forms of expression to advance their goals and amplify their voices.

Civic Engagement in the Public Sphere: Political Engagement

Let’s contemplate a second type of civic engagement—political engagement. This section will discuss rhetoric’s connection to political engagement by examining Dana Schutz’s painting “Open Casket.” The painting reimagines the photo of Emmett Till in his casket following his horrific murder on August 28, 1955. When he was 14, Till—a Chicago native—was killed by white men for allegedly whistling at a white woman during his visit to Mississippi. The press’s printing of images of Till’s mutilated body and the acquittal of his killers is credited as “having galvanized the Civic Rights movement in the U.S.” (Muñoz-Alonso, 2017, para. 4). NBC Chicago produced a docuseries about Emmett Till. In the segment, an investigative journalist traveled to Mississippi to uncover unknown facts about Emmett’s story.

In 2017, Carolyn Bryant, who accused Till of flirting with her while she worked at her parent’s grocery store, disclosed that much of her testimony was false (Pérez-Peña, 2017). Six decades later, Diane Schultz painted her interpretation of the iconic photograph. Schutz painted Till’s face in the abstract (click here to see a jpeg file of the oil on canvas). The smudges of paint were reminiscent of Till’s face being left disfigured and unidentifiable postmortem.

“Open Casket” (2016) hung at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Schultz’s painting sparked conversations about cultural appropriation and prompted the question, “Do white artists have the right to depict Black pain?” (Ejiofor et al., 2017, para. 1). The rhetor responded to the backlash by describing her approach to depicting Till’s disfigurement. She stated that the painting “is not a rendering of the photograph but is more an engagement with the loss” (Ejiofor et al., 2017, para. 5).

Schutz’s painting also prompted backlash for its inclusion in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Take a few minutes to examine this image Scott W. H. Young captured and shared via Twitter. Parker Bright (the rhetor) wore a shirt that read “Black Death Spectacle” while standing in front of the “Open Casket” and blocking the painting from view (Sargent, 2017). The visual image of Bright obstructing others’ views of the painting, coupled with his shirt, advanced an argument that a white person was again using the Black death as a racialized spectacle (Basciano, 2017). In this act of protest, Bright sought to shape the audience’s social reality by using visual and verbal symbols to represent it. Although this is an example of individual action, his rhetorical act contributed to collective action that used rhetorical communication to develop solutions to political challenges (this is the essence of civic engagement!).

In this example, both rhetors were involved in political engagement. Schutz saw her painting as a response to the number of African Americans killed by the police in recent years (Sargent, 2017). On the other hand, Bright picketed the painting daily while barring visitors from viewing the rhetorical act. In both instances, the rhetors possessed rhetorical agency by using a symbol—a body—to spark collective action. A body thus became a symbol pregnant with meaningful intent that sought to persuade an audience. As such, both rhetors used symbolic action to construct viewers’ social realities.

Conclusion: Symbols, Symbolic Action, and Social Reality in the Public Sphere

To review, symbols are objects, words, or images that represent or stand for something else, and their meanings vary depending on context. Symbols have the power to evoke emotions and ideas and establish values. Symbols construct our social reality by influencing how we perceive and interpret our environment. By understanding a symbol’s meaning and cultural frame, we better understand how symbols shape social interactions, identities, and hierarchies that contribute to forming and reproducing a social reality. Symbols transcend language barriers, resonate with people, and are practical tools for expressing identity, solidarity, or protest.

Likewise, symbolic action uses symbols to convey meaning and communicate ideas. Symbolic action provides a powerful means of communication that allows us to express complex ideas, emotions, or values through visual rhetoric. This may be why we often see symbolic action at a protest or memorial site. Symbolic actions shape and reflect our social reality by contributing to constructing meaning and identity. Analyzing symbolic action, such as an activist’s use of a symbol at a protest, helps rhetorical scholars understand the intricate ways communication occurs within civic spaces. By examining symbols, we can uncover underlying meanings, power dynamics, and discursive strategies individuals and groups employ to convey messages and mobilize support.

In closing, studying symbolic action provides insights into practical strategies for engaging citizens and mobilizing collective action. By understanding how symbols resonate with different audiences and provoke emotional responses, rhetors can design more compelling and inclusive engagement initiatives that inspire participation and foster solidarity. Consequently, exploring symbolic action encourages creativity and innovation in civic engagement practices.

References

ACLU. (2017). HR620-Myths and truths about the ADA Education Reform Act. https://www.aclu.org/documents/hr-620-myths-and-truths-about-ada-education-and-reform-act

Basciano, O. (2017, March 21). Whitney Biennial: Emmett Till casket painting by white artist sparks anger. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/mar/21/whitney-biennial-emmett-till-painting-dana-schutz

Black Lives Matter. (2024). About. https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/

Breese, E. B. (2011). Mapping the variety of public spheres. Communication Theory, 21, 130-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01379.x

Burke, K. (1969). A grammar of motives. University of California Press.

Burke, H., & Mallett, W. (2018, June 20). Hamishi Farah’s painting of Dana Schutz’s son exposes the art world’s white fragility. i-D. https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/nekyd8/hamishi-farah-dana-schutz-son-controversy

Calhoun, C. (Ed.) (1993). Habermas and the public sphere. MIT Press.

Cathcart, R. S. (1978). Movements: Confrontation as rhetorical form. Southern Communication Journal, 43(3), 233-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417947809372383

Center for Civic Engagement. (2024). Types of civic engagement. https://civicengagement.illinoisstate.edu/faculty-staff/engagement-types/

Dahlgren, P. (1995). Television and the public sphere. SAGE Publications.

Dictionary.com. (2024). Hot dog. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/hot-dog

Enck-Wanzer, D. (2012). Decolonizing imaginaries: Rethinking “the People” in Young Lords’ church offensive. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 98(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2011.638656

DeLuca, K. M. (1999). Unruly arguments: The body rhetoric of Earth First! ACT UP, and Queer Nation. Argumentation and Advocacy, 36(1), 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028533.1999.11951634

DeLuca, K. M., & Peeples, J. (2002). From public sphere to public screen: Democracy, activism, and the “violence” of Seattle. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19(2), 125-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180216559

Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114-122. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003

Ejiofor, A., Duster, C. R., & Payne, A. (2017, March 26). Creator of Emmett Till ‘Open Casket’ at Whitney responds to backlash. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/creator-emmett-till-open-casket-whitney-responds-backlash-n736696

Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 109-142). MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1974). The public sphere: An Encyclopedia article (1964). New German Critique, 1, 49-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/487737

Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger, Trans.). MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1992). Further reflections on the public sphere. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere. MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1998). On the pragmatics of communication (M. Cooke, Trans.). The MIT Press.

Hauser, G. A. (1998). Civil society and the principle of the public sphere. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 31, 19-40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40237979

Icsman, M. (2018, March 13). 7,000 pairs of shoes were outside U.S. Capitol to represent children killed by guns. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2018/03/13/7-000-pairs-shoes-were-outside-u-s-capitol-represent-children-killed-guns/421433002/

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690-707. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152

Klofstad, C. A. (2011). Civic talk: Peers, politics, and the future of democracy. Temple University Press.

Kornfield, S. (2021). Contemporary rhetorical criticism. Strata Publishing, Inc.

Kweku, E. (2024, January 4). The thin blue line that divides America. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/04/opinion/thin-blue-line-capitol.html

Levendusky, M. S. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. University of Chicago Press.

Mancur, P. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

McGee, M. C. (1980). “Social movement”: Phenomenon or meaning? Communication Studies, 31(4), 233-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510978009368063

Michaels, B. (2020, April 6). The royal hot dog summit of 1939. History & Headlines. https://www.historyandheadlines.com/royal-hot-dog-summit-1939/

Moore-Berg, S. L., Ankori-Karlinsky, L-O., Hameiri, B., & Bruneau, E. (2020). Exaggerated meta-perceptions predict intergroup hostility between American political partisans. PNAS, 117(26), 14864-14872. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001263117

Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C. J., & McNeal, R. S. (2008). Digital citizenship: The Internet, society, and participation. MIT Press.

Muñoz-Alonso, L. (2017, March 21). Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial sparks protest. artnet. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/dana-schutz-painting-emmett-till-whitney-biennial-protest-897929

Nir, L. (2017). Disagreement in political discussion. In K. Kenski & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 713-730). Oxford University Press.

Palczewski, C. H., Ice, R., Fritch, J., & McGeough, R. (2022). Rhetoric in civic life. Strata Publishing, Inc.

Pérez-Peña, R. (2017, January 27). Woman linked to 1955 Emmett Till murder tells historian her claims were false. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/27/us/emmett-till-lynching-carolyn-bryant-donham.html

Rauch, J. (2007). Activists as interpretive communities: Rituals of consumption and interaction in an alternative media audience. Media Culture Society, 29, 994-1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344370708434

Sargent, A. (2017, March 22). Unpacking the firestorm around the Whitney Biennial’s “Black Death Spectacle.” Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-unpacking-firestorm-whitney-biennials-black-death-spectacle

Sillars, M. O. Defining movements rhetorically: Casting the widest net. Southern Communication Journal, 46(1), 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417948009372473

Simons, H. W. (1970). Requirements, problems, and strategies: A theory of persuasion for social movements. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 56(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335637009382977

Stewart, C. J., Smith, C. A., & Denton, Jr., R. E. (2012) Persuasion and social movements (6th ed.). Waveland Press, Inc.

Thin blue line. (2024). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thin_blue_line#:~:text=The%20thin%20blue%20line%20symbol,the%20US%20Capitol%20in%202021.

Van Boven, L., Judd, C. M., & Sherman, D. K. (2012). Political polarization projection: Social projection of partisan attitude extremity and attitudinal processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 84-100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028145