Chapter 11: Rhetoric and Narrative

This chapter discusses the relationship between rhetoric and narratives in three parts. The first introduces key concepts related to narratives, including the inside/outside of narratives, form, genre, and narrative frame theory. The second section of the chapter addresses Walt Fisher’s narrative paradigm and the concepts of narrative coherence and narrative fidelity. The final section [recording forthcoming] describes the narratives that facilitate “speaking for others” and intersectional correctives to hegemonically white, cis-gender, and upper-middle-class narrative point-of-view.

Watching the video clips embedded in the chapters may add to the projected “read time” listed in the headers. Please also note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same tested content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recordings

- Part 1: Form, Genre, and Frame Theory (Video, ~12m)

- Part 2: Narrative Paradigm (Video, ~12m)

- Part 3: The Problem of Speaking for Others [recording forthcoming]

Read this Next

- Johnson, Paul Elliott. “Walter White (ness) lashes out: Breaking Bad and male victimage.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34.1 (2017): 14-28.

Part 1: Form, Genre, and Frame Theory

Narratives have many different components that make them rhetorically relevant. They are reflections of an audience’s values: a story is never just a story. They are about the people telling them, about ways of envisioning the future, or about the contemporary problems that those tellers are confronted with.

Narratives are ways of shaping public memory or retelling events that have happened in the past. They allow us to remember what has happened or to retell these moments as alternate futures. They organize how we interpret public events that we encounter in our everyday lives. Many people have tried to make sense of the Covid-19 pandemic by watching films like Outbreak or Contagion. Narratives also reflect a dominant ideology because they reflect the values not just of the people who create them but of the people who read and watch them, making them a part of their lives.

Inside and Outside

Narratives have an inside and an outside. The inside is usually talked about as the diegesis, and the outside is usually talked about as the extra-diegesis. In a written narrative, the elements that occur in the timeline of the story form the diegesis. Things that happen in the story but fall outside the scope of the story’s events are extra-diegetic. For instance, a story may be about characters whose lives were changed by September 11, 2001. The things that happen to these characters would be part of the diegesis. But if September 11, 2001 were not explicitly a part of the story, they would be extra-diegetic if those events occurred before the story ever began. In films, diegetic and non-diegesis sound define what is available ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ the story. If a character turns on a radio in a film, the sounds are audible to both the characters and the audience, then that sound is diegetic. If ominous music plays and is only audible to the audience but not the characters on screen, then that noise would be extra-diegetic.

In the opening moments of the film Jaws, the diegetic sound consists of the splashes of characters swimming through the water; you can hear the water as if you were yourself swimming. But the extra-diegetic noise starts when the familiar “Jaws” theme starts playing. It’s not audible to the characters; it’s only audible to the people watching. For that reason, we can say that it is “outside” of the narrative.

In the opening moments of the film Jaws, the diegetic sound consists of the splashes of characters swimming through the water; you can hear the water as if you were yourself swimming. But the extra-diegetic noise starts when the familiar “Jaws” theme starts playing. It’s not audible to the characters; it’s only audible to the people watching. For that reason, we can say that it is “outside” of the narrative.

Narrative Time

Narrative time describes the way that stories are ordered as a progression of events. Sometimes the order in which the story is told is not identical to the linear progression of time. Narratives may begin in medias res, where events are already happening or have already happened. They both happen step-by-step and as an overall ‘arc’ that connects the beginning to the end. They happen as brief moments of surprise and opportunity and as the unfolding of deeply plotted events.

- Fabula describes the chronological sequence of events in a narrative. Sometimes stories are told from beginning to end, without any detours. Not all stories are told linearly, however. Many stories involve flashbacks or prolepsis (a foreshadowing or flash-forwards). Sherlock Holmes, a detective fiction, is a story that is famous for taking the reader through a chronological sequence of events only to route them to an earlier moment in time when the detective explains their deductive reasoning. The fabula is the timeline that we would construct if we were to untangle all of the events in the narrative, creating a timeline that puts them back in their linear order from beginning to end. The sequence of the fabula may or may not correspond with how the narrator actually tells the story.

In the example video above, a series of events unfolds “out of order,” which only becomes apparent at the end. If we were to put all of these events into the first-second-third linear sequence in which they happened, this would be the fabula [Spoiler warning]: [extra-diegetically] the main character had and raised a child, they grew apart, and the child left, dramatically. Then [diegetically] the character made a bao bun and fanticized that the bao became a child, that she raised the bao, and eventually the bao decided to leave in dramatic fashion. She then eats the bao. As she is crying in bed, the main character’s son returns and offers some pastries. The two eat the pastries and cry together. The final scene depicts the main character, her partner, her child, and her child’s new partner all in the home making baos together.

- Sjuzhet describes the re-presentation of those events in whatever sequence the narrative presents them. In other words, if the events in the narrative occur in first, second, third order, then that is the sjuzhet. If the narrative begins in the middle, returns us to the past, and takes us to the end, then that is the sjuzhet. If the narrative is a collection of different stories that start and end at overlapping times, then that is the sjuzhet. It is time in the narrative voice of the story as it is told.

In the example video above, the story begins with the main character making bao buns. The bao turns into a baby, which the main character cares for. The bao starts to grow. Over time, the bao grows apart from the main character until one day, the bao decides it is time to depart. They have a heated argument, and prevents the bao from leaving. She then eats the bao. As she is crying in bed, the main character’s son returns and offers some pastries. The two eat the pastries and cry together. The final scene depicts the main character, her partner, her child, and her child’s new partner all in the home making baos together.

- Metonymy as a narrative trope describes the moment-to-moment slippage in a story. Every story is composed of one or many scenes. The metonymic movement of the story is how the story moves from scene to scene, from moment to moment over the narrative’s duration.

More traditionally, metonymy is a rhetorical trope, having to do more with speech than with narrative. It is often described as a “part” standing in for the object itself. For instance, the phrase “all hands on deck” substitutes a part of a sailor for sailors themselves. The phrase “the oval office” substitutes a part of the White House for the institution it represents. The key connection between narrative and rhetorical metonomy is the slip from part to object. In rhetoric, metonymy slips from one part of the object to a name by which it is more conventionally known. In narrative, metonymy slips from one moment of the story into another, which is different but related to the one that came before.

- Metaphor as a narrative trope describes the overall slippage of a story, its total narrative arc. It is how a beginning transforms into an end, putting these two distinct moments into a concrete relationship with one another. For example, in the original Star Wars series, the narrative trope of metaphor describes the overall transformation of Luke Skywalker from a Tatooine farmer into a swashbuckling, empire-defeating, Oedipus-complex-confronting Jedi.

As a rhetorical trope, metaphor puts A into a relationship with B such that some qualities of A are transferred onto B. Narrative does this with a central character, idea, or protagonist. If something lasts from the beginning to the end of a story, it will have some of the same qualities, but will also in most cases have dramatically transformed.

- Kairos is a rhetorical term that signifies “the opportune moment.” To be aware of and use kairos means that one has an awareness of their situation and has the ability to respond to it with words. In narratives, kairos signifies the sudden and the surprising. It is the organization of narrative as a “now,” in the sense of an episode in a larger drama or a striking moment during which dramatic tension may resolve. For example, Dr. Megan Foley argues that the O.J. Simpson trial’s news portrayal employed a “kairotic” temporality because it “seized the present moment to craft a usable past” about racism in the courtroom.

- Chronos is a rhetorical term that describes the deep time in which events unfold. It is the overall time of the narrative and the past and future that extend beyond the narrative’s boundaries. Dr. Emily Winderman argues that the TLC television show A Baby’s Story uses a chronic temporality because each episode tells a story in which the viewer is led to anticipate the family’s completion. The introduction of a newborn provides narrative resolution to birthing drama.

Kairos is the time of contingency; chronos is the time of history. Kairos is a sense of time as occasion; chronos is a sense of time as duration. Kairos figures time as an episodic point; chronos figures time in a sequential line. Kairos emphasizes that rhetoric hinges on timely opportune moments; chronos emphasizes rhetoric’s historical contextualization (Foley 2010, p.71)

Formal and Aesthetic Elements

Narratives also have formal and aesthetic elements. Formal elements are those that structure the narrative. Aesthetic elements are those that occur in narrative because of the cultural context of the story. For example, the plot is a formal narrative element because it places the characters on a path that will eventually lead to some kind of resolution. There is typically one or more dilemmas that the characters must confront. Their (in)ability to resolve this conflict is what brings the narrative to its ultimate conclusion. By contrast, characters are often aesthetic elements of the narrative. Character development describes the actions and relationships among actors in a story, which is often derived from a specific cultural context. Because characters are often reflections of the time and place represented in the story, they will also reflect the values and virtues of the time in which it is set. The professions of different characters can often seem dated or timeless. In Oedipus Rex, the blind seer Tiresias is a strange character for a contemporary audience because it emerges from a unique cultural context. A related figure that we might see in narratives today (e.g., economists, risk assessors, or therapists) will likely appear similarly dated from a future point in human history.

Formal and Generic Elements

Narratives are also categorized and reshaped by genre or conventions that allow stories to be widely recognizable and appreciated by wide audiences. Genres create a pattern of expectation, such that some of the best stories make us question our expectations of what the characters will do or make us jump with a twist ending. Both “form” and “genre” refer to ways of organizing narrative. So, what is the difference?

Form and Genre are two important ways of describing the recognizable organization of narratives. According to the description provided here, forms are the particular logical elements that may occur within a given narrative, genres are arrangements of those elements as recognizable kinds of narrative.

Forms are akin to the building blocks of narrative. They are durable, repeatable elements that may appear as features within many different narratives. Form arrange symbols and organize language in ways that give it a recognizable and repeatable order, like a figure of speech. Forms can build tension and alert you to the fact that a “scary” sequence of events is taking place. In the video below, the musical form of “the four-chord song” uses a similar sequence of notes, played at a variety of tempos, to create a range of different songs.

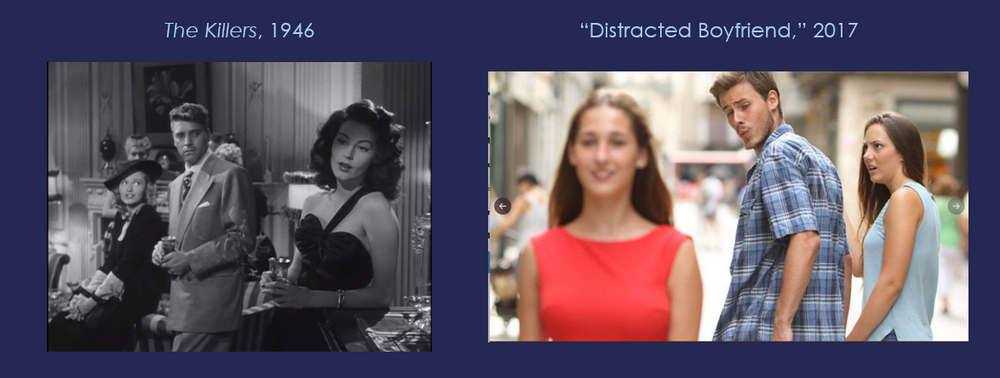

Within narratives, forms are small-scale ways of arranging action and organizing language, giving these a recognizable logical order. It can also be understood as a repeatable sequence or as a figure of speech. Forms can be picked up and then used in a variety of different contexts. They are also ambivalent concerning the ethical or political goals that they serve. Studying form alone cannot tell us which forms are correct or better or worse. Instead, they serve a number of different purposes. When studying forms, we have to think about where and how these forms are being used. The following video offers an excellent example of forms and how they may be picked up, repeated, and recur in many different texts. Minimally, forms can accomplish two functions: (1) they can create the same meaning using different messages, and (2) they can create different meanings using the same messages.

(1) Forms can create the same meaning across different messages. For example, the “distracted boyfriend meme” may be understood as a form when we witness the same elements in a similar arrangement within a different image or text. This meme has a precursor from The Killers, a film from 1946. When we recognize the similarities between these images, we can see how a similar meaning occurs in very different messages whose creation is separated by over 70 years. In a nutshell: form is a way to create the same meaning across different messages.

(2) Forms can also create different meanings using the same message. Often, memes are useful for exactly this reason: they allow us to communicate various messages using the same format or template. The image below is of Brittany Broski, the star of the “Kombucha Girl” meme. On the left, Broski’s signature facial expressions carry the captions “We need to have a talk” and “We need to have a taco.” But this form, the very same image, can carry a different meaning as well. The image on the left shows Broski’s face both disgusted at climate change and optimistic at the prospect of doing something about it. In this case, “Kombucha Girl” produces a form that creates different meanings using the same message, the same template.

Genres are names for categories of narrative. Genres emerge when some number of forms appear together as a consistent feature among different narratives. They may also change over time, as different genres sometimes merge to form new categories of common storytelling. (For example, “horror-comedy” and “dramedy” are recent examples of how distinct genres of narrative have come together to create new formal unities).

Genres are constellations of formal elements. They are not identical to form because they assemble forms and materialize when several different forms cluster together. When we watch a horror film such as The Shining, many formal features come together to create a widely recognizable contribution to the genre of horror films. The music, images of large unoccupied spaces, characters running or limping across the screen with weapons, the voice-over about people in isolation experiencing a mental breakdown, and of course Jack Nicholson’s changing demeanor all indicate that watching the film will be a frightening experience.

Genres also set audience expectations about coherence and resolution. When we watch a movie that belongs to a certain genre, we have expectations associated with it. When those expectations are violated, different things can happen: we might not enjoy ourselves because the movie isn’t the one we hoped to see. It might create a new genre by blending existing formal elements. Genres also structure the interpretation and reception of public events according to the interests of a dominant culture and ideology.

When the formal elements of a genre are re-configured, they create new kinds of stories. Below, you’ll find an example of genre expectation violation. Extra-diegetic elements like the music and the narrator’s voice interrupt what we would expect. If form describes the interchangeable, repeatable organization of narrative elements, then genres describe a constellation of forms that cluster together to tell stories in recognizable ways.

Narrative Frames

Narrative frames are ways that public events are constructed through a narrative. Two critical communication theorists use “frame” to describe narratives: Kenneth Burke and Shanto Iyengar.

Comic and Tragic Frames

Kenneth’s frames are borrowed from Aristotle. They are the comic frame and the tragic frame. For Burke, the same story can be told as a comedy or a tragedy. The difference lies in how we see the motives of the characters.

- The comic frame is a viewpoint that would have you see others as mistaken rather than evil. In the clip below from Veep, Selena Meyer and her aides are incapable of doing their jobs, which is the main reason why you can see them as mistaken rather than as terrible people.

- The tragic frame is a viewpoint that would have you see others as evil rather than mistaken as calculating or as deliberately as deceitful. Here’s a similar clip from the television show “House of Cards,” representing the executive branch doing despicable things. The calculative and manipulative characters displayed here are deliberately immoral and are “tragic” because they are fully aware of the consequences of their actions.

Episodic and Thematic Frames

Shanto Iyengar’s media frames account for how news stories are repeated and told in a political context. It is traditionally understood in terms of the way that news stories are organized. The clip below captures both the “episodic” and the “thematic” frame as they appear in the political campaign speeches of several candidates in the 2012 presidential election.

- The episodic frame depicts public issues in concrete instances or public events; the episodic “makes for good pictures.” Its key characteristic is the snapshot or the close-up. It is about isolated events disconnected from a greater context. They are “human interest stories” that are reducible to the motives of individual actors. Something surprising has happened or is happening, but for no particular reason other than the psychology of the people involved.

In the example above, the episodic frame condenses what we know about a person by using names like “Joe the plumber” or “Mayor Pete.” It is about singular individuals and events and doesn’t offer a larger context to develop their importance or relevance.

- The thematic frame places public issues in some general context. They establish a history and structure that has allowed the events to occur the way they have. Often, thematically framed narratives take the form of a “takeout” or “background” report directed at the general outcomes of policy or event. The thematic frame would, for example, draw attention to conditions of gentrification as the reason for greater homelessness or stock buybacks as the explanation for mass layoffs. This mode of telling suggests some greater reason that would explain why things are as they are.

In the example above, the thematic frame describes the structural and economic reasons for educational cutbacks, job loss, and health insurance. In the case of prisons, a thematic frame would point to the racial, social, and economic conditions that make such institutions profitable or which dispose certain communities to be policed at significantly higer rates.

Part 2: The Narrative Paradigm

A Lecture by Dr. Emily Winderman

The narrative paradigm is Walter Fisher’s theory of narrative. This section is about defining the narrative paradigm and will contrast this framework with the rational world paradigm. Then when we think about what makes a narrative persuasive. Rhetorically we will draw upon two key concepts: narrative coherence and narrative fidelity.

What is a Paradigm?

A paradigm is a conceptual framework, a universal model that calls people to view events as an interpretive lens for events around them. A paradigm is like a magnifying glass: different magnification levels might lead you to see a similar phenomenon in different ways. The rational world paradigm is one magnifying glass among many others that allow us to interpret and see and make meaning about what’s going on in our world. So, it’s not belief-based, really, but more of a question of epistemology or how we know what we know. So how do we know what we know? We know it through stories.

In Ancient Greece, a philosophical paradigm was privileged over a rhetorical paradigm. That’s why the sophists really were castigated for their elevation of the rhetorical ways of knowing and being in the world. Many people operate according to a scientific and rational world paradigm. Of course, that’s not “everyone” because people obviously can and do reject scientific facts. Such people are acting according to a different narrative paradigm. Nevertheless, the national world paradigm tends to be privileged most in our society right now.

The Narrative Paradigm

Walter Fisher developed the Narrative Paradigm, where he refers to humans as storytelling animals. The idea of storytelling animals really just says that storytelling is so foundational to what it means to be humans that it might as well be as if we were barking dogs (aka storytelling animals). He doesn’t believe that stories are an instrumental form of rhetoric that you either bring a list of statistics or a good narrative story like you may have learned in your public speaking class. On the other hand, Fisher believes that all types of communication are in and of themselves a type of story or narrative. So for him, the narrative is absolutely foundational to rhetorical and communication. Humans are narrative beings who experience and understand life as a series of ongoing narratives. So what is a narrative for Fisher? It’s pretty similar to what you might expect. It’s symbolic action – words and or deeds that have sequence and meaning for all of those who live, create and interpret them.

So first, what are the components of a story? There are characters: the protagonist and the antagonist. Some people move the story along, and others perform a requisite amount of emotion. You also have rising action, a climax, falling action, and finally, a moral to the story or a big takeaway that contains a lesson and should impact our future actions.

Comparing Paradigms

Between the rational world paradigm and the narrative paradigm. On the rational world paradigm side, we have that humans are rational creatures who make decisions based on arguments. The speaking situation determines the ways that we make those arguments. Rationality is how we know what we know. Our epistemology is a rational epistemology. We argue based upon good reason, and the world is considered a set of rational puzzles to be rationally resolved. On the other hand, humans are storytellers. We make decisions based on good reasons, which vary based upon any situation. History and culture determine those good reasons. Narrative rationality (what makes a narrative quote on quote good or persuasive) is based on its coherence and fidelity. That means the world is not a set of logical puzzles but rather a set of stories that are constantly creating and recreating our lives.

Key Concepts: Coherence and Fidelity

Narrative rationality describes how to evaluate the worth of a story based upon standards of coherence and fidelity. Coherence is how a story hangs together; fidelity is how, whether, and for whom a story ‘rings true’.

Narrative Coherence

Narrative coherence describes the degree of internal consistency within a story: characters act reliably, events unfold in a manner that is expected, the story and the plot hang together with few contradictions. When a character suddenly appears in different clothing because of poor editing, or when plot lines are dropped, it draws the audience’s attention to the absence of narrative coherence. Narrative coherence is the equivalent of making an argument in the rational world paradigm. When the characters behave reliably, the story works, and we trust the plot’s consistency. We become extremely wary when details are left out.

The lack of narrative coherence appears in the above clip because many of the elements we might expect to be present in a narrative, such as characters, plot, and resolution are absent. There appears to be no motivation for the images nor any clear connection between them, save for the unsettling emotional experience that they are designed to produce. As Gabe Lewis (the character in the above video played by Zach Woods) says: story or narrative is itself comforting. A narrative that interrupts our expectations also disrupts the sense of pleasure we get by connecting beginnings and ends or understanding a story’s moral or purpose. Instead, it leaves us with the impression that the narrative is incomplete, something has been left out, or that there is more to the story than has been told.

Narrative Fidelity

Narrative fidelity describes how narrative “rings true” with a real-world set of experiences. It is similar to realism in the sense that a narrative appears to capture an authentic experience or an actual event in a way that is faithful to its source material. It also describes the consistency between the values embedded in a narrative message and the values that the viewer, listener, or reader brings to their reading. Understood as the values shared between an audience and a narrative, narrative fidelity to have several criteria:

- First, a set of shared values must be present in the narrative. For instance, a character must have the kinds of characteristics or experiences that an audience will recognize in themselves. Alternatively, even if audiences do not share the values of a protagonist, they may identify with the kinds of values associated with different characters’ struggles or that arise as a result of the events that transpire over the duration of the story.

- Second, there must be a connection between shared values and the narrative plot. If shared values are embodied by a character or characters, the audience’s assessment of these figures should not be incidental or haphazard, but driven by the organized action and resolution of the narrative’s different events. For instance, a flashback may encourage an audience to identify with an otherwise unlikable character, or a character may undergo a set of trials that change their disposition in ways that make them more sympathetic to the reader/listener/viewer.

- Third, adherence to shared values must be tied to a specific set of outcomes or consequences. An audience must not only identify with a character, but their experiences must bear out the consequences of adhering to those values in ways that ring true for those watching, reading, or listening. Adhering to a shared set of values, such as loyalty, perseverance, or courage may result in hardships that nonetheless allow the audience to identify with the complexities of doing the right thing. Alternatively, breaking with such values may bring about consequences to demonstrate that sticking to one’s principles is important — or not as important as it is often touted to be.

- Fourth, there must be some measure of consistency between an audience’s values and the values espoused by the narrative. In other words, a narrative’s values must be relatable in the sense that they fit the contexts available to an audience. Whereas some narratives originating from cultural contexts or time periods that are distinct from our own may give us the impression that there is something timelessly true about the values espoused, others may feel alien to us because the context is so starkly different from the one we inhabit.

- Fifth, the values of a story must align with (or noticeably depart from) recognizable public morals. There should be a shared sense that the values captured by a narrative also resonate with or challenge the kinds of values that are shared by a wider group, or public, to which the reading/watching/listening audience belongs.

So when we affirm a story as having narrative fidelity, or when we say a story rings true, we affirm its shared values and invite ourselves to be influenced by them. At minimum, we understand the kinds of values that the narrative espouses and can relate when those values are rewarded. We may also be surprised or taken aback when those values are challenged, dismissed, or revealed to be more complex than we might have initially believed.

The above story is faithful to experience: the values in question concern the character’s passion for chili, which is relatable, heartwarming, and ultimately, tragic. For teachers like myself during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, all the hard work, planning, and preparation that went into our courses had to change at a moment’s notice. Like Kevin (played by Brian Baumgartner), you too may put a lot of work into a task or make elaborate plans only to have this work and labor unexpectedly vanish. Many of us can relate to the experience of slipping on the metaphorical chili you’ve planned for days or weeks. Ultimately, narrative fidelity is present here because Kevin’s misfortune feels familiar; it is the way that his fiction rings true.

Part 3: The Problem of Speaking for Others

The final section of this chapter is about how stories are often told from a limited point of view that shuns other perspectives, modes of storytelling, and experiences. A common criticism of the 1990s television show Friends, for example, is that it depicted an unattainable New York City apartment, one with many rooms, appliances, and neighbors who regularly interacted. The main characters of the show are all white, and they lived in lavish circumstances. However, their jobs included a waiter (Rachel), a chef (Monica), a musician/masseuse (Phoebe), an actor (Joey), an information technology (IT) manager (Chandler), and a history professor (Ross). Consider the following passage from Juliet Schor’s 1998 The Overspent American:

Part of what’s new is that lifestyle aspirations are now formed by different points of reference. For many of us, the neighborhood has been replaced by a community of coworkers, people we work alongside, and colleagues in our own and related professions. And while our real-life friends still matter, they have been joined by our media “friends.” (This is true both figuratively and literally–the television show Friends is a good example of an influential media referent.) We watch the way television families live, we read about the lifestyles of celebrities and other public figures we admire, and we consciously and unconsciously assimilate this information. It affects us.

When poet-waiters earning $18,000 a year, teachers earning $30,000, and editors and publishers earning six-figure incomes all aspire to be part of one urban literary referent group, which exerts pressure to drink the same brand of bottled water and wine, wear similar urban literary clothes, and appoint apartments with urban literary furniture, those at the lower economic end of the reference group find themselves in an untenable situation. Even if we choose not to emulate those who spend ostentatiously, consumer aspirations can be a serious reach.

Advertising and the media have played an important part in stretching out reference groups vertically. When twenty-somethings can’t afford much more than a utilitarian studio but think they should have a New York apartment to match the ones they see on Friends, they are setting unattainable consumption goals for themselves, with dissatisfaction as a predictable result. When the children of affluent and impoverished households both want the same Tommy Hilfiger logo emblazoned on their chests and the top-of-the-line Swoosh on their feet, it’s a potential disaster.

Friends is not just unrealistic; it is one of many stories representing “everyday” people who ignore how unattainable their living circumstances are. These kinds of narratives imagine a predominantly white and wealthy America that does not exist in the United States, making debt creation a natural outcome.

The Problem of Speaking for Others

In the essay “The Problem of Speaking for Others,” Linda Alcoff questions whether some circumstances warrant a person to speak on someone else’s behalf. She begins her essay by acknowledging that at the current moment, “speaking for others is arrogant, vain, unethical, and politically illegitimate.” (6). People speak from specific positions of class, race, gender, culture, and ability, and a person’s position cannot be assumed in advance. Additionally, people in privileged positions speaking for historically oppressed peoples often make matters worse, counterproductively perpetuating oppression. Prompted by the problems mentioned, Alcoff generates two premises (15):

- Premise 1: Positionality and context are always relevant to a message.

- Premise 2: Certain contexts (which are always unpredictable, in some way or another) ally themselves with oppression or resistance to oppression, thus perpetuating inequality.

The first premise requires that the speaker’s ethical obligation is to know the person with whom they are speaking to the best of their ability, understanding that elements of their experience and history can and do remain inaccessible. No amount of research reveals someone else’s context. The second premise describes the hierarchy of power; it deals with “rituals of speaking,” which “are politically constituted by power relations of domination, exploitation, and subordination” (15).

Alcoff distinguishes between “speaking for” and “speaking about” and relies on this phrasing throughout her essay. Alcoff insists that one cannot speak for (or on behalf of ) another person without speaking about (or revealing one’s own assumptions) them. Likewise, one cannot speak about another person without also speaking for them (9). The novel American Dirt received such a negative reception when its first published because its white author spoke about – and in the voice of – Chicano immigrants while using offensive stereotypes and racist imagery. As Mariana Ortega argues, this kind of misrepresentation may stem from “knowing, loving ignorance” on the part of white authors of western European descent. It may be, in other words, that the intentions of the author are to be more inclusive or to center Black and Brown voices in their work. However, if this “loving” work is also ignorant with respect to the experiences and positions of those written about, then it is not “loving” because it still has harmful effects.

Those guilty of this kind of loving, knowing ignorance have learned the main sayings of such well-known feminists of color as hooks, Lorde, and Lugones, and are aware of Spelman’s claims about the problems of exclusion in feminist thought. They theorize and make claims about women of color. However, they do not check whether in fact their claims about the experience of women of color are being described with attention to detail and with understanding of its subtleties. In other words, this ignorance goes hand in hand with the production of knowledge about the experience of women of color. The result of this ignorance is that women of color continue to be misunderstood, underrepresented, homogenized, disrespected, or subsumed under the experience of”universal sisterhood” while “knowledge” about them is being encouraged and disseminated and while feminism claims to be more concerned and more enlightened about the relations between white women and women of color.

Alcoff also explains the problems of not speaking for others, including retreating, avoiding responsibility, eschewing criticism, and maintaining immunity.

- First, she argues that if people must tell their own stories (and themselves alone), then the result will be “a retreat into a narcissistic yuppie lifestyle in which a privileged person takes no responsibility for her society whatsoever” (17). If one can only attest to one’s own experiences (which she calls an “illusion”), then that assumes one person’s life has no bearing on other people’s lives (20).

- Removing oneself from any situation in which one is either listening to or sharing one’s story is not a neutral stance because it allows oppression to continue (20). She argues that “[t]he declaration that I ‘speak only for myself’ has the sole effect of allowing me to avoid responsibility and accountability for my effects on others” (20). Alcoff calls out the problem of this avoidance: “it is both morally and politically objectionable to structure one’s actions around the desire to avoid criticism” (22), yet the retreat approach allows just that—an immunity to criticism.

Alcoff then provides four suggestions that one should consider prior to speaking for someone else, including the following:

- Analyze why speaking for someone else is necessary, especially to avoid asserting dominance over the situation.

- Consider our own positions– the stories we tell about ourselves and the racial, cultural, familial, gendered, and ethnic context we come from — without using it as a disclaimer or an excuse.

- “[R]emain open to criticism” (26)

- Analyze the effects of the speech, “where the speech goes and what it does there” (26).

Intersectionality

Intersectionality refers to a framework developed by Kimberle Crenshaw to understand the ways that structural forces, such as legal institutions, schools, and the health care system, create multiple and overlapping forms of social oppression, specifically against Black girls and women. It is related to narrative because it suggests that telling one’s story may be more complex by the many structural factors contributing to their experience. Specifically, gender and race may function in ways that dismiss credibility and ability. Such effects render the experiences of Black women invisible and more subject to public scrutiny, disciplinary action, and policing by the legal system.

Kimberle Crenshaw theorizes intersectionality to account for identities at a structural level. (6) According to Brittany Cooper, “intersectionality’s most powerful argument is . . . that institutional power arrangements, rooted as they are in relations of domination and subordination, confound and constrict the life possibilities of those who already live at the intersection of certain identity categories” (9). This arrangement of power affects the kinds of narratives we can tell about Black, Indigenous, and other minoritized groups in several ways. On the one hand, people who live at the intersection of marginalized race, gender, and class categories are more subjected to harmful stereotypes and discrimination while the reasons for this unequal treatment are made invisible. The stories that are told are often about them but “without” them, in other words, without including their unique voices or perspectives. By contrast, other predominantly white and heterosexual-identifying peoples are made “invisible” because this position is often unacknowledged or unspoken. Narratives are often told from a white and western European perspective, although this positioning goes unacknowledged. As Crenshaw argues:

Because discursive constructions of whiteness are typically unmarked and unnamed in personal, academic, and public discourse, they present a constellation of challenges for rhetorical scholars who are interested in the ideological role of whiteness in intersecting discourses about race, gender, and class.

Importantly, intersectionality is not a research method because this understanding of the framework threatens to disappear black women (19-20), deemphasizes racism (19-20), and “erase[s] the intellectual labor of [intersectionality’s] black women creators” (20). As an alternative, Cooper advocates employing intersectionality “as a conceptual and analytical tool for thinking about operations of power” (21) and as “one of the most useful and expansive paradigms we have” (21). It is a reasoning that should animate our reasons for telling stories and understanding the complexity of Black women’s experiences. It can also help us deepen our understanding of the structural factors that place intersecting identities into difficult double-binds where they are deprived of agency and power.

Secondary Readings

- Johnson, Paul Elliott. “Walter White (ness) lashes out: Breaking Bad and male victimage.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34.1 (2017): 14-28

Additional Resources

- Alcoff, Linda. “The problem of speaking for others.” Cultural critique 20 (1991): 5-32.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8: 137-167.

- Flores, Lisa A. “Towards an insistent and transformative racial rhetorical criticism.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 15.4 (2018): 349-357.

- Flores, Lisa A. “Between abundance and marginalization: The imperative of racial rhetorical criticism.” Review of Communication 16.1 (2016): 4-24.

- Foley, Megan. “Serializing racial subjects: The stagnation and suspense of the OJ Simpson saga.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 96.1 (2010): 69-88.

- Johnson, Paul Elliott. “Walter White (ness) lashes out: Breaking Bad and male victimage.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34.1 (2017): 14-28.

- Lewis, William F. “Telling America’s story: Narrative form and the Reagan presidency.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 73.3 (1987): 280-302.

- Ott, Brian L., and Eric Aoki. “The politics of negotiating public tragedy: Media framing of the Matthew Shepard murder.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 5.3 (2002): 483-505.

- Towns, Armond R. “The (racial) biases of communication: rethinking media and blackness.” Social Identities 21.5 (2015): 474-488.

- Terrill, Robert E. “Put on a happy face: Batman as schizophrenic savior.” Quarterly journal of speech 79.3 (1993): 319-335.

- Rushing, Janice Hocker, and Thomas S. Frentz. “The Frankenstein myth in contemporary cinema.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 6.1 (1989): 61-80.

- Frentz, Thomas, and Janice Hocker Rushing. “” Mother isn’t quite herself today:” myth and spectacle in The Matrix.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19.1 (2002): 64-86.