Chapter 14: Rhetoric and Ideology

This chapter is about ideology and myth. It will connect the theory of the sign to the concept of ideology. The first part of the chapter will cover the materialist theory of ideology, offering some background on some of its major features, including value and exploitation. Then it will discuss the transition from the theory of the “sign” to “myth.” Finally, it will explain the ideograph as an example of how rhetorical scholars have adapted it.

Watching the video clips embedded in the chapters may add to the projected “read time” listed in the headers. Please also note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same tested content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recordings

- Part 1: Ideology and Myth (Video, ~30m)

- Part 2: Agency, Persona, and Speech Act (Video, ~30m)

Read this Next

- Hall, Stuart, “From language to culture: linguistics to semiotics,” In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Vol. 2. Sage, 1997.

- Walter Greene, Ronald. “Rhetorical capital: Communicative labor, money/speech, and neo-liberal governance.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 4.3 (2007): 327-331.

Written Assignments

Part 1: Ideology and Myth

| The Materialist Theory of Ideology | |

|---|---|

| Idealism Ideas, images, concepts |

Materialism the material work, the actual relationships between people and the (economic) hierarchies between them |

| DETERMINE the material world, the actual relationships between people and the hierarchies between them. |

DETERMINE Ideas, images, concepts |

One common way that Marx’s materialist theory of ideology is often summarized is as “flipping Hegel on his head.” In other words, Marx conceived of his own project as a transformation of the Hegelian “idealist” framework. In Hegel’s worldview, the world is composed out of ideas. The “psychic” or “ideational” world of the “soul” takes precedence and shapes the ways in which individuals understand themselves, and determines the physical world which is just an expression of logic and consciousness. In a crossed-out portion of The German Ideology, Marx summarizes this position himself:

Hegel completed positive idealism. He not only turned the whole material world into a world of ideas and the whole of history into a history of ideas. … All the German philosophical critics assert that the real World of men has hitherto been dominated and determined by ideas, images, concepts, and that the real world is a product of the world of ideas. This has been the case up to now, but it ought to be changed. … According to the Hegelian system ideas, thoughts and concepts have produced, determined, dominated the real life of men [sic], their material world, their actual relations. (crossed-out portion of The German Ideology, p. 30)

Marx’s view is the opposite of Hegel’s. He argues that the world is materialist in the sense that there is an objective reality outside or beyond our ideas about it. The purpose of Marx’s project is to demonstrate that our empirical, material reality determines our conceptual, ideational experience of that world. More concisely, how the individual “subsists” or provides for themselves determines culture. Economic structures organize this physical, material life to create our “psychic,” (internal, cognitive, or mental) life and correspondingly, the relationships that exist between human beings.

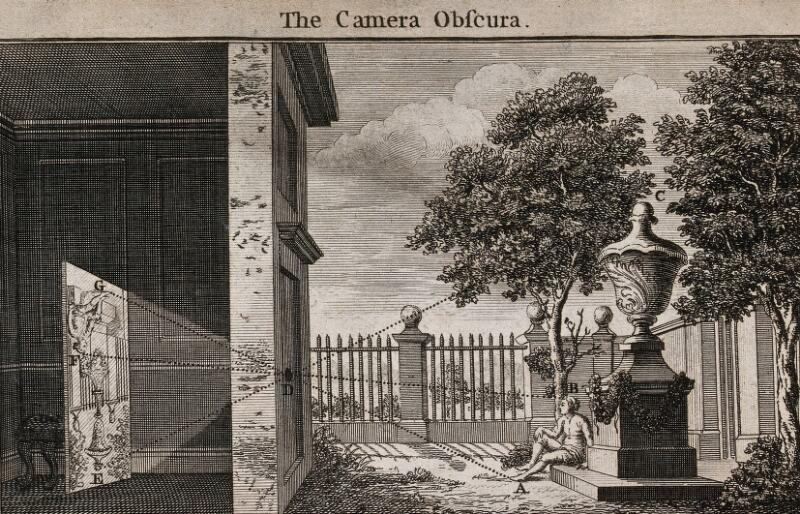

If in all ideology men and their relations appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process. (Marx, The German Ideology, p.42.)

The “camera obscura” quotation is especially famous because it also “flips” Hegel’s established hierarchy in which “ideas” determine “material” existence. It may look that way, but in fact, the material world generates and constrains our ideational, mental life. The metaphor of the camera is also deeply significant because it invokes a connection between our consciousness and the technologies available to describe it. For Marx, we are all little cameras: looking at the world as if our ideas created what was in front of us, when in fact, the world creates and limits what we can — and cannot — think and do. If in Hegel ideas are determinative of the real world, in Marx, the real, material world is determinative of our ideas. The camera is therefore more than a metaphor; it is a way of using rhetoric to describe how the invisible part of human vision creates the limit of what can be thought.

Ultimately, the “flip” that we will be attentive to is the “flip” from idealism to materialism, paying close attention to the way that actual, real, and lived experience creates social consciousness. This is also how the materialist theory of ideology links to our previous weeks’ discussions: the theory of ideology argues that our material conditions determine the signs we use, the symbols we share, and how we imagine and represent ourselves to ourselves, for instance, as free and independent from the systems that we are a part of.

What is Ideology?

In this class, we will define ideology as the religious, artistic, moral, and philosophical beliefs contained within and perpetuated by a society or culture, and which are determined by the material circumstances that occasion them. Ideology may also be explained in terms of an economic structure in which material is hoarded by a ruling ‘superstructure’ to produce the collective consciousness of the proletarian ‘base’. According to Marx, in any society, the ruling ideas are those of the ruling class. According to Ziyad Husami, however, even if this is true, this does not mean that other modes of collective consciousness do not ALSO exist, and that contained within these other ideas are other notions of justice that would render the whole of capitalist ideology unjust or immoral.

Basic premises of “ideology.” Marx’s theory is often (over-)simplified in the following way: (1) Ruling classes control the material organization of the world (2) Ruling ideas are imposed on lower classes, who internalize it and (3) Each ‘class’ has its own ideology. For that reason, ideology is often called a theory of class consciousness. It describes our consciousness as a function of class hierarchies. Stuart Hall specifically expands upon the idea that ideological consciousness is particular to distinct groups of people, refusing a blanket characterization of the proletariat as a single homogenous group. Different people internalize ideology differently, even if it is the *same* ideology that they have internalized. Let’s watch this old-timey cartoon about Marx’s theory of class consciousness, and which also helps us to connect the theory of the ideology to some ideas we’re already familiar with, namely, the theory of the sign.

Labor Value and Labor Exploitation

Marx distinguishes between three kinds of value, “exchange value,” “labor value,” and “use value” in the following way.

- “Exchange value” is the price of a commodity, and represents the purchaser’s ability to command labor, to compel its production.

- “Use value” describes the tangible features of a commodity that can satisfy some want or need. Use value serves social needs, but it does not represent the social relations of production.

- “Labor value” or “labor power” is the value of the labor required to produce a commodity. The value of labor covers not just the value of wages but the value of the entire product created by labor.

Capitalism functions by hoarding “exchange value” at the expense of “labor value.” Although it’s sometimes presumed that the exchange value of an item — the price we pay — is equal to its labor value — or the cost of producing it — wealth depends upon extracting a greater exchange value from a commodity than the labor value used to produce it. Ideology would consist, in this case, in the convictions that arise because of contradictions like this one, and how individuals reconcile the fact that their labor is less valuable than the cost of the goods and services that they produce.

In Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1884, Marx theorizes labor not to be liberating, but as a source of estrangement. The logic of estrangement is rooted in political economy, more specifically a labor theory of value.

Additionally, under capitalism’s designations of private property, workers add value to raw materials via their labor, creating commodities to be bought and sold. For Marx, labor cannot liberate as it is inherently coercive. Individuals must work to survive, and in doing so generate profit for their employers. Marx argues that labor estranges the individual from their material, physical experience in four ways:

- (1) It estranges them from the product of their work; such that the producer of consumer goods doesn’t relate to what they make as a “craftsman” but instead as an “interchangeable part” in the production process.

- (2) estrangement from the activity of production; such that they do not have control over their labor schedule, the procedure for ‘making’ goods, the rules of the organizational hierarchy to which they belong, or the parts of the production process that are separate but related to their own.

- (3) estrangement from species-being; meaning that they lose touch with other people who may inhabit other jobs or live in different places who have a related existence related to their own work. If we can imagine a worker at a “General Mills” factory who thinks of themselves as opposed to another person in their own position at “Nestle,” that gets us close to this kind of estrangement. What these folks can’t recognize is the fact that they are in the same or a similar position.

- (4) estrangement of “man to man.” Beyond identification with other people who occupy similar or related positions, labor estranges us from other people in general, regardless of where they stand or what their social position is relative to ours. We become less available because labor stifles our ability to relate to one another, to empathize, to see others as part of a common community.

Work does not help an individual come to understand the world, and their place in it, but actually obscures it, entrenching them within a partial and illusory version of it. Marx is explicit that liberation requires revolution, or, practical change to things in the physical world. Marx reaches this conclusion in The German Ideology, in which he lays out a materialist conception of history.

“The production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men [sic] — the language of real life” (42).

From Sign to Myth

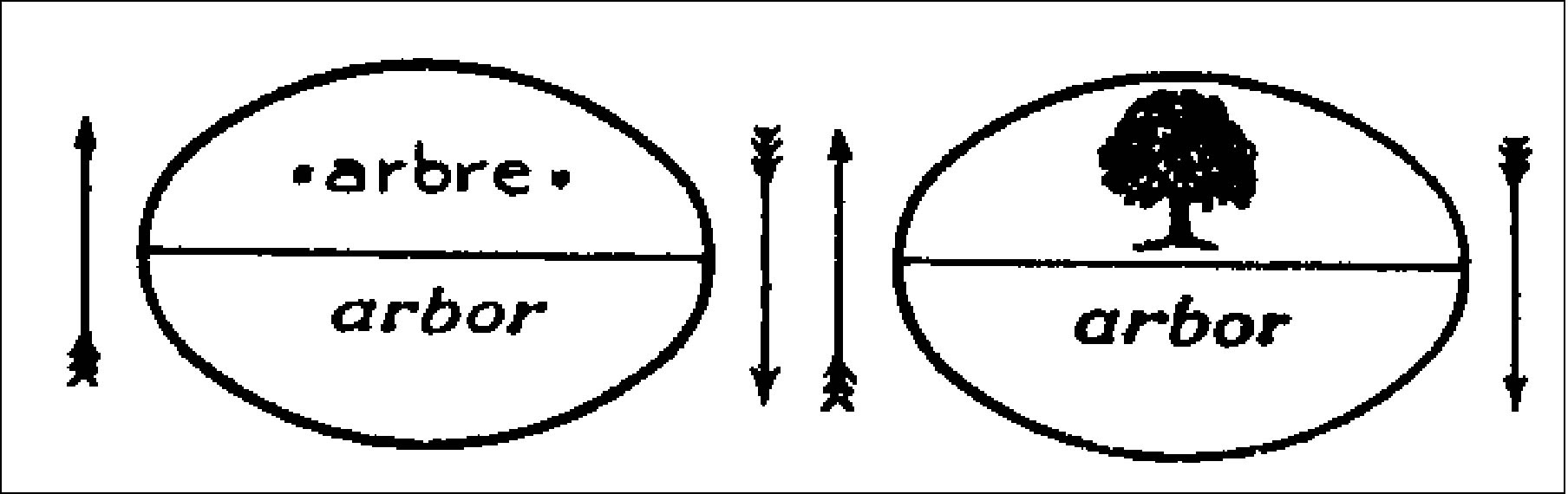

As discussed in earlier chapters, the theory of the sign is often attributed to Ferdinand de Saussure, whereas the theory of the symbol is attributed to the 20th-century rhetorician Kenneth Burke and the 19th-century philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced ‘purse’). As we have discussed, Saussure is known for connecting the theory of the sign to general rules of language, whereby the sign gives a form to shared social meaning and its transformation.

| Peirce: What is a Representation/Symbol? | da Saussure: What is a Sign/Language? |

| Sign-as-Icon: likeness/perception | Langue: a system with finite, determinate rules. Parole: language in situ, or in its practical use. Diachronic: longitudinal characteristics Synchronic: momemtary characteristics |

| Sign-as-Index: reaction/reference/cause and effect | |

| Sign-as-Symbol: “likeness” has no necessary connection to the object to which it refers, a sign which relies upon the shared understanding of ideas. | The basic unit is the sign. The sign is the unity of the signifier and signified. The signified is the implied concept. The signifier is the sound-image. |

The theory of ideology takes the relationship between the “conceptual” or “ideational” meaning (or what the sign represents for us) and the “material” signifier (or the verbal and visual expression used to convey it) and translates it as the distinction between base and superstructure.

The superstructure is the world of ruling ideas or concepts; it is the site where ideology’s meanings exist. These meanings depend on a material ‘base’ — the classes and culture who produce these meanings, which are extracted from them, commodified, and sold back to them. Often “superstructure” is translated as “ruling class” whereas “base” is rendered as the “proletarian” or “laboring” classes.

In the last chapter, we discussed how the sign gains its force and value through its differential relationship to other signs. A sign is a sign by virtue that it is not other signs, that it means something in its difference from other signs that inhabit its (langue) sign system, and which evolve through individual speech acts (parole). This is, for instance, how Michael McGee and Roland Barthes conceptualize the ideograph, which at a given moment of time draws its meaning from a field of related ideologically charged signs.

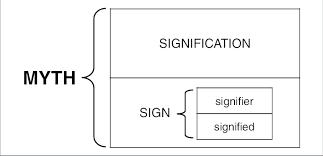

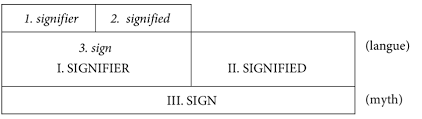

Below are two different diagrams for myth as a function of the sign. The sign, composed of a signifier and a signified (or first-order elements). When they combine to form a sign, it is what Roland Barthes called “second-order signification.” Myth operates at the level of “third-order signification” and describes is what happens when the sign is elevated above other signs, or when it wields control over a larger sign system. Myth also describes a representation’s ideological force. A given sign can acquire an additional meaning or signification, acquiring the weight of “myth” as part of a system of representations that organize popular beliefs. This belief structure can be (for instance) religious, nationalistic, colonialist, or capitalist. When ideology operates through the logic of the sign, it means that the concepts implied by our language contribute signifiers to a larger reservoir of shared meaning-making that defines our relationships to governing (e.g. colonialist, imperialist, or capitalist) structures.

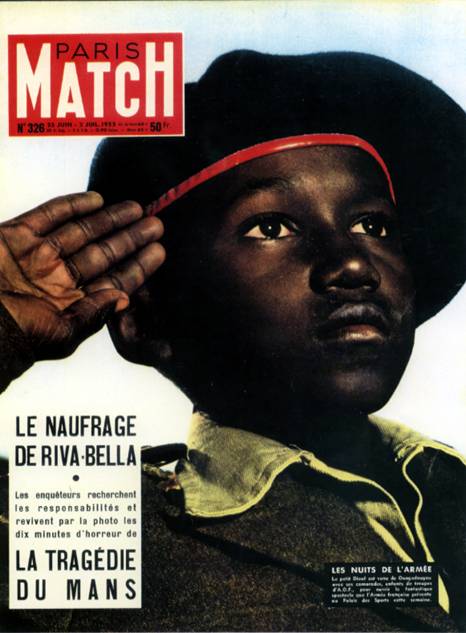

Barthes’s demonstration of second-order signification is a magazine cover whose mythic signification is about French colonialism in Algeria occurring at the time of his writing.

Barthes describes the cover in the following way:

I am at the barber’s, and a copy of Paris-Match is offered to me. On the cover, a young [child] in a French uniform is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the [French flag]. All this is the meaning of the picture. But, whether naively or not, I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this [child] in serving [their] oppressors.

The second-order, or sign value of the image is that the signifier, the saluting boy in a beret, corresponds to the concept of the child-soldier. The third order, or mythic sign value of the image, is what it means “to Barthes”: That this “child-soldier” is not coded as just any soldier but as a sign of French national-colonialism in which the recruit is a ready and willing participant in their own colonization. As third-order signification, the viewer knows that the child salutes the French government and implies that national ideals of extractive, invasive warfare are worthy of being upheld because this colonized, militarized child supports it.

The whole of France is steeped in this anonymous ideology: our press, our cinema, our theatre, our popular literature, our ceremonies, our Justice, our diplomacy, our conversations, our remarks on the weather, the crimes we try, the wedding we are moved by, the cooking we dream of, the clothes we wear, everything, in our everyday life, contributes to the representation that the bourgeoisie makes for itself and for us of the relationships between man and the world.

Disavowal

Let’s look at another example of myth, dramatized in the film “They Live,” which is explained in this documentary hosted by psychoanalyst Slavoj Zizek. In the film, the main character, “John Nada” awakens to the mythic value of the signs around him. They no longer signify things like “money” or “relaxation,” but instead start to signify directly at the level of myth, they are written over with the true, exploitative meaning that they would otherwise conceal.

As the video shows, the theory of ideology is about more than just the commonly accepted meanings attached to commercial objects. It is about the larger system or structure that creates and determines those meanings, and how attached to those meanings we as individuals become. Ideology also explains the idea that we convince ourselves out of what these third-order signs *actually* or *really* mean. This is called disavowal. When we cultivate beliefs that give us an escape from the reality that we inhabit, we are disavowing reality. Disavowal is like refusing to put on the glasses or to reject reality because we know we can’t handle it.

Disavowal is the way that the subject “knows very well” how they act in the service of ideology but “nonetheless” act in ways that work against their own self-interest, in the service of capitalism, or both at once.

What they do not know is that social reality itself, their activity, is guided by an illusion, by a fetishistic inversion. What they overlook, what they mis-recognize, is not the reality but the illusion structuring their social activity. They know very well how things really are, but they are still doing it as if they did not know (p.32).

Another example of disavowal is purchasing products that claim to be “green” because we are aware that consumerism destroys the environment but need to be reassured that our own personal consumption is not the problem. Disavowal is a way that ideology produces more symbols, as ways to justify its continued existence and self-perpetuating.

Lastly, the process of “putting on” the glasses, of awakening to the mythic signification of objects, is called “de-mystification.” Demystification is the unveiling of myth and the revelation that reality is not what we once perceived it to be. It is what happens at the end of the clip when the actor “wakes up” to the world as it is.

The Ideograph

In “The Ideograph: A Link Between Rhetoric and Culture,” Michael Calvin McGee adapts Barthes’ theory of “myth” to rhetoric. McGee explains that the real problem occurs when scholars maintain that “myth” and “ideology” are conflicting ideas. The ideograph is a model that brings together “ideology” and “myth” and that basically repeats the theory of myth we have just discussed. It accepts that individuals have the potential to control power through symbol-use, and acknowledges the strong influence of power over individuals. McGee argues that

“ideology in practice is a political language, preserved in rhetorical documents, with the capacity to dictate decision and control public belief and behavior” (p. 5).

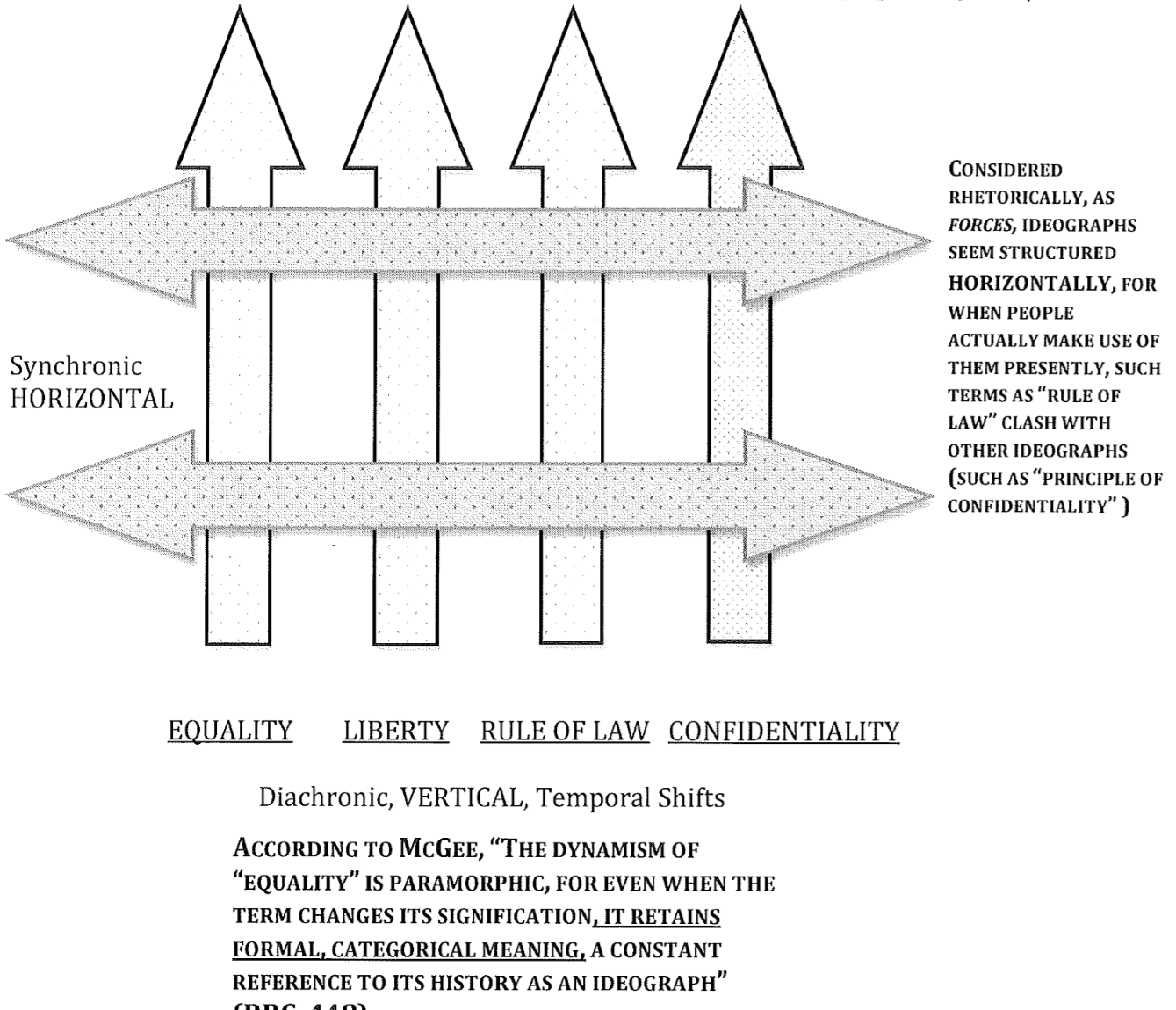

Ideographs, which are used within this language, expose interconnected “‘structures’” of public motives” that represent diachronic and synchronic formations of political consciousness.

[These synchronic/diachronic formations] “control ‘power’ and influence […] the shape and texture of each individual’s reality” (p. 5).

McGee writes that the only way to diminish power is through prior persuasion, conditioning the meaning of an act before it takes place. Individuals are “conditioned” mainly through certain “concepts that function as guides, warrants, reasons, or excuses for behavior and belief” (p. 6). The result is a “rhetoric of control” that suggests persuasion will be effective on an entire community (p. 6). The words that become the vocabulary of this rhetoric (like “liberty,” “freedom of speech,” and “rule of law”) form the basic units of ideology — McGee calls these ideographs. They signal certain accepted propositions to all members of a community. Ideographs are not invented but become part of people’s real lives as “agents of political consciousness” (p. 7). Ideographs unite and divide nations because they are a definitive part of the social and material conditions into which various individuals are born, and one community will have accepted a set of ideographs that differs from others. In accordance with McGee’s “A Materialist’s Conception of Rhetoric,” ideographs represent a usage that is social and material, but cannot represent pure thought or truth.

Ideographs are like signs because they exist within synchronic and diachronic timeframes. Considered rhetorically, as forces, ideographs are synchronic, meaning that they describe the way that people actually use them ‘on the ground’ or in practice. At the synchronic level, say, at the start of the 21st century, an ideograph like “equality” might clash with other ideographs like “freedom,” “liberty,” and “rule of law” and “confidentiality.” Through the emergence of various situations, they may conflict with other ideographs and through this conflict may change its meaning, as can be seen with Nixon attempting to alter the meaning of the ideograph “confidentiality” in relationship to “rule of law.”

But diachronically, “equality” shifts depending on when we are describing it. It is, in McGee’s words “paramorphic,” meaning that even when the term changes its signification, it retains meaning in relation to its historical meanings, its meaning in relation to all of the previous meanings that it might once have had. The diachronic dimension references the usage of an ideograph throughout time. Individuals look through an ideograph’s usage historically to locate “touchstones” and “precedents” that help judge what is an acceptable use of that ideograph. As McGee writes, meanings may evolve, but the current meaning of an ideograph is determined in part by its past context of use. For example, Patrick Henry’s explanation, “give me liberty or give me death!” may have been fabricated by the historian William Wirt.

Overall, McGee argues that understanding both the vertical and horizontal dimensions of ideology are necessary — we must see ideology as a “grammar” (diachronically) to know what changes have happened, and also as a “rhetoric” (horizontally) to know how present situations alter the relationships among ideographs.

Part 2: Agency, Persona, and Speech Act

In this chapter, we’ll cover the following: agency, persona, and speech act theory. I’ll try to connect ideology to each of the terms, and again at the end of the recording. Let’s start by defining the three core concepts in this recording, and provide an explanation of how ideology is involved.

How is Ideology related to Agency, Persona, and Speech Act?

- Agency, or “the capacity to act”: Ideology limits the capacity to act, or otherwise informs the motives ‘behind’ why a speaker or an audience acts in the way they do in relation to a claim.

- Persona, or “the implied speaker/audience”: Ideology is the shared substance of identification produced through a speaker’s invocation of their own position, the audience’s position, as well as excluded, “eavesdropping,” and “collusive” parties.

- Speech Act, or “an utterance that performs as an effect of being stated.”: Ideology is the thing that is brought into existence through speech acts as a relationship and hierarchy between different speakers and audiences. Speech acts also have the ability to transform the subjectivity of the speaker or those spoken to/about.

Three Kinds of Rhetorical Agency

Agency is often defined as “the capacity to act.” When rhetoric enters the picture, it poses the following questions: who has the greatest capacity to act: the speaker/rhetor, the listener/audience, or the speech/text?

Rhetorical Agency “is the capacity to act, that is, to have the competence to speak or write [or engage in any form of symbolic action] in a way that will be recognized or heeded by others in one’s community.” (p. 211)

(1) Rhetor-centered Agency: Speakers have the capacity to create and adapt to audiences.

This is a traditional understanding of rhetorical agency rooted in the “intentional” framework of representation. Because the speaker creates a world of representations and symbols for the listening audience, they are understood to have the greatest agency. A speaker can create the impression of a threat or danger, they can calm an audience’s fears, and they can construct a shared reality that they and their audience may inhabit together. Adapting to an audience is often understood in terms of the speaker’s ability to be creative or inventive. If agency lies with the rhetor, then we understand the speaker to be deliberately crafting appeals for the heterogeneous audiences (i.e. of varied composition) that they might encounter. Adapting to an audience can also take the form of double meanings (see also: the fourth persona and the eavesdropping audience) where some members of the audience are more “in” on the message of the speech than others.

(2) Audience-centered Agency. Audiences have the capacity to act because they may accept or refuse the meaning offered by a speaker, and the effectiveness of a speech is ultimately determined by whether an audience acts in accordance with the worldview set out by the speaker.

A great speech is only as great as the effect it has on an audience, and that audience’s willingness to pick up the message and run with it. Because an audience may refuse to act (e.g. not going out and voting in the face of a speaker’s urging) or act in ways that contradict the speaker’s message (e.g. wearing face shields instead of masking) the audience is understood to have the greatest power when it comes to rhetoric because they interpret and act on the rhetoric that is set before them. Additionally, different audiences are differently enabled in the world, depending on whether they possess capital, resources, or ability. Different audiences are marked by race, gender, embodiment, class, and age. For that reason, an audience has agency when it is empowered to be an agent of change, and when there are few constraints (i.e. obstacles or limitations) that would prevent them from acting on (or against) what a rhetor offers in their message.

(3) Text-Centered Agency: A speech, text, or another form of rhetoric has the greatest capacity to act because it will travel in ways that neither a speaker nor an immediate audience can control or comprehend.

Once spoken, written, or otherwise drawn into existence, rhetoric has a life of its own. Consider, for instance, a popular meme template that circulates widely. The original “text” (e.g. the “spider man pointing” meme”) may be drawn out in ways that could not have been anticipated by the “rhetor” (e.g. the animators and creators of the meme in 1967) or the “audience” for whom it was created and who interpreted it. Because the message took on a viral life of its own, the message itself has the greatest capacity to act.

By this understanding of agency, meaning is not “eternal,” it does not last forever and it changes over time. Likewise, humans are not isolated from one another or from history because the sum total of interactions is what lends a given instance of rhetoric form and meaning. Rhetorical agency in this sense is perhaps better understood as existing within a larger system of interactions.

This form of agency is also embraced by the posthumanist tradition, which rejects the human agent as the primary source of change. Instead, that agent is a participant in the larger network of which they form a part. Agency occurs not solely within the realm of human intention or the direct result of human action but somewhat outside of human control.

Let’s consider an example, George W. Bush’s “Bullhorn Speech” in the wake of September 11, 2001, and think about how the different kinds of agency describe what is happening in the video.

- Rhetor-centered agency in this video might describe the intentions of the speaker, their willful crafting of a speech. In this case, we are talking about George W. Bush, who presumably came with a speech and with an intended message for the audience: we care about first responders. However, the fact that he loses control over the message also suggests that rhetor-centered agency might not be the best way to account for the communication that is happening.

- Audience-centered agency in this video describes how the audience changes, adjusts, and re-assembles what “George” is saying to them. It is less what the speaker intended and more what the audience hears and how they respond. This is a better way to think about this speech, perhaps, because there is a clear moment when the speaker loses control of the message. Instead, the audience reacts based on what they *think* they heard, and not George’s intended message.

- Text-centered agency is perhaps the best way to explain this clip, and consists in the idea that it is neither the speaker nor the audience that is ‘in control’ or has the ability to act, but rather the signs and symbols that are being cited. The phrase “I can hear you” is what has agency here. It can be addressed to a person or to a group. It can have multiple meanings, literally, your words register on my eardrums, or figuratively, your desires and wishes are known to me. The message controls the possible reactions to the situation.

Agency and Ideology

Given that agency describes “the capacity to act,” ideology limits the capacity to act, or otherwise informs the motives ‘behind’ why a speaker or an audience acts in the way they do in relation to a claim. Ideology seems to limit our agency. The beliefs we adhere to create a window upon the world that reminds us of what is and is not possible, what we can and cannot do, what is and is not acceptable. If we adhere to the idea that upward mobility is the only way to “make it” in the world, then this belief may limit the jobs we take, the opportunities we seek out, or even our willingness to step away from the positions we have. The belief guides us to act in certain ways while restricting us from behaving in others. When, for instance, we disavow the world around us, or subscribe to beliefs that exist to justify the ideological system we inhabit, ideology limits our ability to think and act in the world because those actions work in service of this ideology. However, de-mystification creates the perception that we have agency because we gain the ability to read signs and symbols in a way that we previously did not. With demystification, we gain a capacity to read, see, and understand, and therefore, to also act differently with respect to the reality that we perceive.

Persona

In Rhetorical Studies, the word “persona” is a way to describe the characters conjured by a speech or speaker. Only in the case of the “first persona” does it refer to the “character” of the speaker themselves, or the kind of individual that the speaker makes themselves out to be. In all other cases (“second,” “third,” “fourth,” and “eavesdropping”) the word persona refers to the audience that the speaker creates. It describes, for instance, how the speech creates a vision of who the audience is for the listening audience, generating an identity with which to identify (second persona). It also describes those audiences who are excluded, omitted, or hidden by the speech (third, fourth, and eavesdropping persona) but which are nonetheless hailed by the speech.

- The First Persona “is the author implied by the discourse.” (p. 213) There is no one author to attribute the concept of the first persona because it was for a long time assumed that the intentions of the speaker generated the audience’s imagination of itself as well as the speaker’s own authoritative speaking position.

- The Second Persona is “the implied audience for whom a rhetor constructs symbolic actions.” (p. 213) The second persona is, in a way, an ‘original’ form of ideology criticism because it was developed by Edwin Black as criticism of the anti-Communist John Birch Society, which metaphorically linked communism to cancer to constitute an audience of like-minded individuals who would take up the society’s conservative stance and aggressively paranoid mindset.

- The Third Persona refers to the “audiences not present, audience rejected or negated through the speech and/or speaking situation.” (p. 214) These are the audiences excluded, but who are necessary for the speech to exist at all. A commemoration speech about the building of the White House that does not acknowledge the history of enslaved persons who labored to build it is an example of this kind of speaking — the audience may or may not be present as hearers, but they are both crucial, necessary for the speaker to make their address and at the same time, deliberately omitted as a means of dehumanizing this audience or pitting them against those people who are being addressed.

- The Fourth Persona “is an audience who recognizes that the rhetor’s first persona may not reveal all that is relevant about the speaker’s identity, but maintains silence in order to enable the rhetor to perform that persona.” (p. 217) The scholar who develops this theory, Charles Morris, uses the example of mid-twentieth century FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who publicly conveyed messages about a “sex crime panic” while subtly dropping cues in his speeches that only a ‘knowing’ audience would be able to decipher or know. These messages conveyed messages about Hoover’s own gender, which gay listeners would be ‘in’ on but would be unable to vocalize or address. The fourth persona is this “collusive audience,” who is ‘in’ on the speaker’s message but who act as a silent party for their dog whistles or doublespeak.

- The eavesdropping audience “is an audience whom the rhetor desires to hear the message despite explicitly targeting the message at a different audience.” (p. 217) This can be for two reasons: (a) To limit room for response by, or the agency of, the eavesdropping audience or (b) To allow the eavesdropping audience to feel empowered because they are not being criticized even as they hear criticisms made against others.

The eavesdropping audience is most often credited to Gloria Anzaldua, who “addresses a specific group of women, ‘third world women,’ not all women (and not to any men). She linguistically and symbolically reinforces this address in the first and last sections by opening with “Mujeres de color,” thus placing first-world women (and men) in the position of reading mail unintended for them. They become the eavesdroppers. The letter moves first-world women (and all men) to a borderland when it does not address the letter to them, while it empowers “Mujeres de color” by literally addressing them as the primary subjects. First-world women are written about. Men are just absent; they are not written to, nor do they write. Men and first-world women are uninvited eavesdroppers and, hence, suspended from a critical position. They are reminded of their difference. They are reminded that they constantly tokenize third-world women and deny differences among women. The letter reverses power relationships so that first-world women are allowed access without input, a condition “Mujeres de color” often experience. (p.218)

As a final note about these different kinds of persona, there are circumstances when there are multiple personas at work in a single speech or written work. For example, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is addressed to multiple audiences: It is explicitly addressed to “My Dear Fellow Clergymen” — meaning white moderates, who comprise a direct second persona, the implied listeners or readers of this document. It also indirectly speaks to all Black people in the United States as King attempts to persuade them to risk their bodies in nonviolent civil disobedience in civil rights protests. This is the audience who is invited to “eavesdrop” on the conversation. White moderates appear unwilling to act, so it is other African Americans who must be persuaded to push for social change. (p. 219)

“Like King, [black readers] can view themselves as agents who need not and will not suffer the indifference of white moderates, who can break free of external restraints without losing self-restraint, and who can work from within American society to make fundamental changes in the way they conceive themselves and are conceived by others.” (Leff and Utley)

Let’s consider another example: an anti-child abuse advertisement that is designed for reception by multiple audiences. In this case, the advertisement is the “speech” or “rhetoric” that constitutes a variety of different characters.

The first persona is the persona of the speaker or crater of the advertisement. It consists in their intended meaning as well as the position of the “socially responsible company,” who is authorized to act on behalf of suffering children.

The second persona is the implied audience of the message, the person or people to whom the advertisement is addressed. The implied audience is the adult who is reading the ad, and who sees themselves in the way that the company would like. This reader might, for example, recognize that harm done to children is invisible, and supports the idea of a socially conscious company doing something about it.

The third persona is the excluded audience of the message who is nonetheless necessary for its existence. It is the fact of the person who abuses or harms children, the person who cannot or is not “persuaded” to stop this abuse, but who must exist for the advertisement to also have meaning.

The fourth persona is, finally, the audience who “colludes” with the speaker, who is ‘in’ on the message even if no one else knows it. It is a message within the message for the hearer, for whom it was designed. This is the child, who alone is able to see, hear, or read the message for its subversive meaning. In this case, the child may also be the eavesdropping audience, whose relative inconspicuousness allows them to be empowered because they are not being criticized even as they hear criticisms made against others.

Persona and Ideology

Persona, or “the implied speaker/audience” is implicated in ideology because creating a persona requires that we identify with an ideology. This means that a shared system of belief is necessary to create a shared impression of the speaker, audience, as well as “eavesdropping,” and “collusive” parties. In that sense, persona describes the ideological disposition the speaker would like the audience to have, as well as the ideological disposition shared by the audience and speaker. It is a way of talking about the common ground established between these characters, and how that “ground” creates the conditions of exclusion or nonparticipation. One may be part of the same ideological belief system or be a part of it by virtue of being excluded from it. Ultimately, persona allows us to think about the expression of ideology as the relative position of the audience to a message that influences their system of belief and representation.

Speech Acts

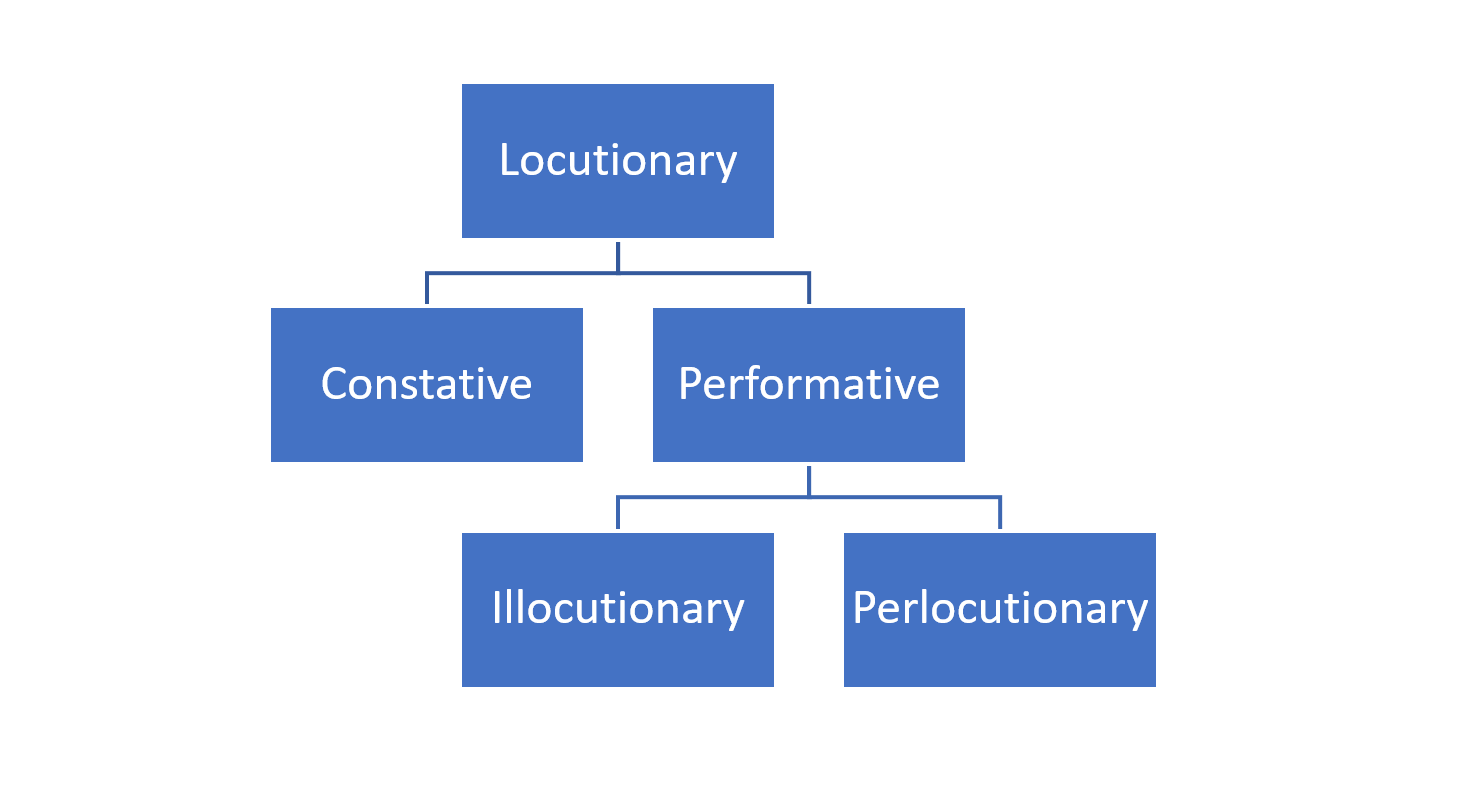

The theory of speech acts is typically attributed to J.L. Austin, a British ordinary language philosopher. His schema of the locution (shown below) offered important and widely cited distinctions between the constative and performatives, and within the category of performatives, illocutionary force, and perlocutionary effects.

The locution is the most general category of an utterance. It is, for our purposes “any” utterance or instance of speech. A locution may be constative or performative.

A constative utterance is what we most often understand as “denotation,” “reference” or literal meaning. To call an utterance “constative” makes the assumption that the thing said corresponds with a real thing in the world. There is no room for subjective interpretation with the constative utterance; things mean what they mean regardless of the context they occupy. In the example suggested below, “that’s an interesting hot dish,” the word interesting literally means “provoking curiosity or interest.” Free from context, “that’s an interesting hot dish” is a way of describing your contribution to the potluck as novel,

A performative utterance is one that depends upon context for its meaning. Traditionally, it corresponds with the “connotative” or “subjective” meaning of an utterance. But it is also much more than that: when we talk about the performative, the words have an interpersonal force for the people it is addressed to. If we said a performative utterance in one context, it would not necessarily land the same in another. It also lands differently, depending upon the person to whom it is addressed. If I said “that’s an interesting hot dish” to someone from Georgia, where I went to school, it likely wouldn’t bother anyone. But if I were to say the same phrase to a guest in Minnesota, it would land with the force of an insult.

To explain the unique consequences of the performative, Austin divides the performative into two kinds: illocutionary force and perlocutionary effect.

The performative’s illocutionary force refers to statements that have an effect ‘as stated’, or the doing of something as one states it. “I pronounce you both married” is an example because there is something done in the saying of this phrase: it transforms two people from being “engaged” into a family unit with a special personal, religious, and legal significance. One way to think of illocutionary force is as the immediate consequences of the speech act. In the case of “that’s an interesting hot dish,” it transforms the relationship between the cook and the recipient by serving up an insult at the moment.

The performative’s perlocutionary effect refers to consequences not immediately experienced when the speech act is spoken. It may be thought of as a distant or long-term effect of the speech act. Marriage confers a number of long-term consequences that are not immediately felt: a shared bank account, expectations with respect to in-laws, new habits of communication. In the case of the “hot dish,” the statement might strain the relationship between the people involved, or it might provoke the hot-dish maker to seek revenge.

Example: “That’s” an interesting casserole/hot dish”

| Utterances | Definition | Examples |

| Constative | Denotation, meaning free from context | “Interesting” as a denotation. |

| Performative | Subjective meaning or connotation, meaning dependent upon context. | “Interesting” as connotation. |

| Illocutionary (force) | Responds to the speech act as stated. The performance of an act ‘in’ saying something. | “I now pronounce you married” or “The jury finds the defendant not-guilty,” both of which transform the subjectivities of persons.

The performative force is “Insult” |

| Perlocutionary (effect) | The consequential effects upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience, or of the speaker, or of the other | Changes to tax filings of the expunging of criminal records.

The performative effect is “Revenge” |

Up to this point, we’ve been considering performatives that “work,” or that have the intended consequence. When I say, “that’s an interesting hot dish,” and you hear sarcasm, that’s a felicitous performative or one that hits its mark. But speech acts don’t always work the way we intend. When a speech act does not have the performative effect its speaker anticipates, it is called an infelicitous performative. Let’s watch this example:

What does Michael misunderstand about speech acts? He doesn’t understand that “declaration” is a legal and bureaucratic act, not just one you can speak into existence. It’s a speech act that doesn’t hit the mark because it can’t be addressed the way he does. As illocution, it cannot make him into a bankrupted subject (he did that to himself) and as perlocution, it cannot entitle him to the benefits he seeks by claiming this legal status.

Speech Acts and Ideology

Speech acts, or “utterances that perform as an effect of being stated” are related to ideology because ideology creates many kinds of effects through speech. In fact, ideology reproduces itself through speech acts. Speech acts also have the ability to create and misidentify the subjectivity of the speaker or those spoken to/about, thereby subjecting them to repressive or hegemonic ideologies.

A famous example of the speech act is the hail of the police. As you are walking down the street, the police call out “hey you,” and your back is turned to them. The phrase “hey you” is the speech act. The consequences are significant because the recognition — even the incorrect recognition — that you are the person being called out, or that you are the “subject of the hail” is the consequence of ideology. That is the system or structure that has to exist even before those words were said. Ideology calls you into being as a subject, as someone who exists in the same system of power and hierarchy. The illocutionary effect is to turn around in the moment, but the perlocutionary effect is to recognize yourself as subject to the law. This is called interpellation.

Interpellation has many different kinds of effects. Rhetorical scholar Maurice Charland explains that “a people” come together when people write up founding documents. These documents are performative speech acts; they include the American Declaration of Independence or the Canadian Constitution of the Peuple Quebecois. Each of these is performative because they had short and long-term effects for not just one person, but a specific group of people: they named themselves as independent or separate from an existing governing entity. Judith Butler, author of Gender Trouble and Excitable Speech, returns us to the police, saying that these kinds of speech acts often aren’t as explicit as a “hey you.” Instead, they may take the form of legal arguments or personal injuries that can deny the person named of their gender identity. Butler calls this kind of speech act a “violating interpellation,” in which a person is made less-than through ideologically-driven institutions and actors.

Secondary Readings

- Hall, Stuart, “From language to culture: linguistics to semiotics,” In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Vol. 2. Sage, 1997.

- Walter Greene, Ronald. “Rhetorical capital: Communicative labor, money/speech, and neo-liberal governance.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 4.3 (2007): 327-331

Additional Resources

Materialist Rhetorics

- Asen, Robert. “Introduction: Neoliberalism and the public sphere.” Communication and the Public 3.3 (2018): 171-175.

- Asen, Robert. “Neoliberalism, the public sphere, and a public good.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 103.4 (2017): 329-349.

- Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and ideological state apparatuses (notes towards an investigation).” The anthropology of the state: A reader 9.1 (2006): 86-98.

- Bollmer, Grant D. Theorizing digital cultures. Sage, 2018.

- Bollmer, Grant. Materialist media theory: An introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2019.

- Bollmer, Grant. Inhuman networks: Social media and the archaeology of connection. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2016.

- Charland, Maurice. “Constitutive rhetoric: The case of the Peuple Quebecois.” Quarterly journal of Speech 73.2 (1987): 133-150.

- Cloud, Dana L. “The materiality of discourse as oxymoron: A challenge to critical rhetoric.” Western Journal of Communication (includes Communication Reports) 58.3 (1994): 141-163.

- DeLuca, Kevin. “Articulation theory: A discursive grounding for rhetorical practice.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 32.4 (1999): 334-348.

- Gamble, Christopher N., Joshua S. Hanan, and Thomas Nail. “What is new materialism?.” Angelaki 24.6 (2019): 111-134.

- Greene, Ronald Walter. “Another materialist rhetoric.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 15.1 (1998): 21-40.

- Hall, Stuart. “Signification, representation, ideology: Althusser and the post‐structuralist debates.” Critical studies in media communication 2.2 (1985): 91-114.

- Hazard, Sonia. “Two ways of thinking about new materialism.” Material Religion 15.5 (2019): 629-631.

- Marx, Karl. “Wage labour capital.” The marx-engels reader. Vol. 4. New York: Norton, 1972: 167-190.

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The German ideology: including theses on Feuerbach and introduction to the critique of political economy. Prometheus Books, 1998.

- McGee, Michael Calvin. “The “ideograph”: A link between rhetoric and ideology.” Quarterly journal of speech 66.1 (1980): 1-16.

- McGee, Michael C. “In search of ‘the people’: A rhetorical alternative.” Quarterly journal of Speech 61.3 (1975): 235-249.

- McGee, Michael C. “A Materialist’s Conception of Rhetoric.” Rhetoric, materiality, & politics. Vol. 13. edited by Biesecker, Barbara A., John Lucaites, and John Louis Lucaites. Peter Lang, 2009: 17-42.

- McGee, Michael Calvin. “Text, context, and the fragmentation of contemporary culture.” Western Journal of Communication (includes Communication Reports) 54.3 (1990): 274-289.

- Peeples, Jennifer, et al. “Industrial apocalyptic: Neoliberalism, coal, and the burlesque frame.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 17.2 (2014): 227-254.

Speech Act Theory

- Austin, John Langshaw. How to do things with words. Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Butler, Judith. “On Linguistic Vulnerability.” Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. (1997): 1-43.

- Butler, Judith. “Burning Acts, Injurious Speech.” Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. (1997): 43-71.

Rhetorical Persona

- Darsey, James Francis. “Edwin Black and the first persona.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 10.3 (2007): 501-507.

- Black, Edwin. “The second persona.” Quarterly journal of Speech 56.2 (1970): 109-119.

- Wander, Philip. “The third persona: An ideological turn in rhetorical theory.” Communication Studies 35.4 (1984): 197-216.

- Morris III, Charles E. “Pink herring & the fourth persona: J. Edgar Hoover’s sex crime panic.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88.2 (2002): 228-244.

- Cloud, Dana L. “The null persona: Race and the rhetoric of silence in the uprising of’34.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 2.2 (1999): 177-209.

- Doss, Erin F., and Robin E. Jensen. “Balancing Mystery and Identification: Dolores Huerta’s Shifting Transcendent Persona.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99.4 (2013): 481-506.

- Ede, Lisa, and Andrea Lunsford. “Audience addressed/Audience invoked.” Concepts in Composition: Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing (2003): 182.