Chapter 4: Rhetoric and the Freedom of Expression

Emily Berg Paup

by Emily Berg Paup

Key Concepts: parrhesia, isegoria, dialectic, doxa, First Amendment, freedom of speech

This chapter examines the multifaceted nature of the right to freedom of speech and its development and connection to the rhetorical tradition. It will explore these ideas through their theoretical foundations, historical development, and the ongoing struggle to ensure their equitable application.

- Part 1 explores the rhetorical and historical justifications for protecting the freedom of speech, which includes considering the importance of open discourse as a cornerstone of democratic societies for critical thinking and the pursuit of truth. It introduces two ancient greek notions of “freedom of speech,” parrhesia and isegoria, connecting the need for free discourse to the rhetorical concepts of dialectic and doxa.

- Part 2 examines the five freedoms protected in the First Amendment and how the law distinguishes between different types of expression through something called the “Two-Tiered Theory of Speech,” such as political speech and symbolic speech. This section also considers the role and limitations of a free press plays in the circulation of discourse.

- Part 3 chronicles the exclusion of marginalized communities from the full exercise of their freedom of speech, including ways they have actively resisted censorship and made their voices heard.

By examining these diverse facets of freedom of speech, this chapter aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of both the promises and the challenges of this fundamental right.

Part 1: Why Do We Value Free Discourse?

The value of public discourse and the free exchange of ideas is something that has been part of philosophical debate for thousands of years. This first section will explore why the right to free expression is important from a rhetorical and philosophical perspective.

Rhetorical Reasons

The rhetorical tradition emphasizes people’s ability to make good judgments about uncertain problems based on the best possible argument. Of course, this requires healthy argument practices and assumes that those in a position to make decisions will act in good faith. As discussed in Chapter 2, the early rhetorical theorists, known as Sophists, were not only famously criticized by Plato, but they also had a unique worldview that was rooted in argumentation. According to the Sophists, myth, religion, and family were unreliable ways of solving social, scientific, and political problems. Instead, argument, debate, and discussion were crucial tools. Through logos (which means both ‘reason’ and ‘the word’) they believed that individuals could change the world through thought, discourse, and action. Hence, the Sophists sought to instruct individuals in spoken arts that would enable them to secure the agreement of their audiences, navigate uncertain situations, and guide them in forming judgments.

Dialectic and Doxa

There is power here, for if humans learn to use argument to influence the decisions of others, there is great potential for unethical and deceptive speech. This early ethical debate led Plato to raise a crucial question in the rhetorical tradition: Does teaching persuasion equate to promoting deception, resembling mere sophistry? Plato addressed this by distinguishing between rhetoric, which he considered to be concerned with only the appearance of truth, and dialectic, a higher form of discourse where knowledge is acquired, opinions refined, and truth discovered (Jasinski 164-165). Aristotle, too, distinguished between rhetoric and dialectic, albeit with a slightly more positive spin. In the Rhetoric, he noted that although both concern persuasion, rhetoric primarily focuses on adapting to the audience, while dialectic centers on universal truths pursued through logical argumentation (1.1).

The importance of safeguarding freedom of expression is also rooted in the Platonic concept of doxa and dialectic. For Plato, these concepts represent two ways of engaging with knowledge (or episteme). Dialectic is the method Plato advocates for ascending to the intelligible realm of true knowledge (episteme), a process of using reasoning, dialogue, and discourse, whereas doxa refers to beliefs based on people’s worldviews, which can change as times, contexts, and societies change. That is because worldviews are fluid, unstable, and susceptible to persuasion. In The Gorgias, Plato portrays the Sophists as manipulators of doxa, who would use their skills to sway public opinion without regard for truth or justice; who would persuade people toward “belief without knowledge.” Rhetorical theorist Lloyd Bitzer’s writings highlight the lasting resonance of Plato’s concepts over 2,000 years later when he defines rhetoric as “a mode of altering reality, not by the direct application of energy to objects, but by the creation of discourse which changes reality through the mediation of thought and action (4).” Whereas rhetoric and persuasion can influence doxa, dialectical inquiry is meant to create social change through ethical debate. Protecting the freedom of speech opens this space for self-expression, self-fulfillment, growth, and change.

Parrhesia and Isegoria

Just as ancient Athens was the birthplace of rhetorical theory, so too was it the birthplace of “democracy” – a space in which ordinary people could gather and exchange ideas. As introduced in Chapter 1, ancient Athens resembled the early United States because both similarly conferred rights only to wealthy and propertied male citizens. Ancient Athens also provides us with an early model of ‘free speech,’ which it captured in two distinct concepts. The first is parrhesia, or “the license to say what one pleased, how and when one pleased, and to whom.” The second is Isegoria, or “the equal right of citizens to participate in public debate in the democratic assembly” (Bejan 97). Whereas parrhesia accounts for ‘fearless’ speech that puts power dynamics and the law’s use of force on display, isegoria accounts for speech that is free as defined from within the bounds of the law.

In ancient Greece, parrhesia, which is often translated as “freedom of speech,” really meant “frank” or “fearless” speech. Parrhesia bade people not only to share their opinions or beliefs, but also to challenge the doxa, question those in power, and push the boundaries of knowledge, even if it meant doing so at great personal risk. In fact, parrhesia was seen as an essential character attribute in the pursuit of truth and development of knowledge, reinforcing the importance of an environment that protected free discourse. In the Apology, for example, Socrates exemplifies parrhesia by speaking truthfully to the Athenian court, even at the cost of his life. In the Gorgias, rhetoric is portrayed as speech that can manipulate and praises Callicles of his honesty and frankness (487a-e; Walzer 8).

Central to the Athenian idea of parrhesia was that it “allowed the citizens to be bold and honest in expressing their opinions even when outside the assembly and extended to many spheres of Athenian life including philosophy and theatre” (Mchangama 13). For ancient Greek orator Demosthenes, “freedom of speech” was integral to Athenian democracy because of how it and “political debate” could lead to truth (Mchangama 14). “Parrhesia,” according to Jacob Mchangama, “also allowed for a rich intellectual life in Athens and provided both positive and negative confirmation of Demosthenes’s later point about the virtue of permitting dissent against the very democratic order” (15).

Further, the ancient Greeks believed that people had an ethical duty to act with parrhesia. Isocrates redefined parrhesia as a civic responsibility in his work. In 374 B.C.E., Isocrates offers “frank advice” (Walzer 11) in his “Letter to Nicocles” as his “gift to the prince” (Walzer 11). He encourages Nicocles to “regard as your most faithful friends not those who praise everything you say or do, but those who criticize your mistakes.” Isocrates continues, “grant “freedom of speech” (parrhesia) to those who have good judgment…(28). Plutarch extended this idea to personal relationships when in his essay “How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend,” he referred to parrhesia as “the language of friendship” (Walzer 17). He argued that friends have a duty to speak truthfully to each other as a way to cultivate moral character, even if it means offering unflattering advice.

Of course, it is important to remember that only a select group of voices could enact this virtue. Another commonly translated Greek word for freedom of speech is isegoria, which translates to “equal speaking in the assembly,” —a privilege granted to all male citizens of Athens during the democracy in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.E. Citizens would gather in the Ekklesia, a space in which they would try to persuade each other of political policies. As Lu writes, “Isegoria was a crucial conceptual element of Athenian democracy; voting was its conceptual partner. The two concepts formed an integrated unit whereby, under ideal conditions if not necessarily in reality, citizens engaged each other in deliberation in order to come to decisions which represented both what the citizens wanted done, and what best served the community” (28). In addition, while isegoria is often understood to mean “equal right to speech,” there was no such codified right in ancient Athens. Greek society operated a space of privilege that excluded women, slaves, and non-citizens. In this way, isegoria can actually be understood as a “socially constructed power, not a natural power” (Lu 29).

This socially constructed nature of isegoria highlights its role not just in granting some individuals access to spaces of discourse and excluding others, but also in fostering a culture of open dialogue in a community – one in which each individual feels entitled to speak, even if they don’t exercise that right. As Lindsay Rathnam writes, “Equal right of say guarantees the person space in the public realm; it doesn’t matter how valuable or moral or wise their contribution is but rather that they are entitled to be there, to exist, to develop their own selves through their pursuit of their own good” (Rathnam 145). In contrast, parrhesia moves beyond oneself to emphasize the moral duty of truth-telling for the common good. Together, isegoria and parrhesia reflect different dimensions of discourse: one fostering an environment for equal opportunity for speech (in theory), the other (together with dialectic) demanding the courage to confront truths for the sake of the development of knowledge that is foundational to the growth of society.

Both concepts are foundational to understanding how free speech, the pursuit of truth, and rhetoric work together. Michel Foucault’s work on parrhesia emphasizes that while speaking truth to power (or speaking with frankness to a friend), is inherently risky, it is precisely this risk that lends it moral weight and importance . Foucault stressed that parrhesia “comes from ‘below,’ as it were, and is directed towards ‘above’” (Franks 114). Quoting Foucault, Mary Anne Franks points to the idea that the “parrhesiastes is always less powerful than the one with whom he or she speaks…this is why an ancient Greek would not say that a teacher or father who criticizes a child uses parrhesia.” She continues, “but when a philosopher criticizes a tyrant, when a citizen criticizes the majority, when a pupil criticizes his or her teacher, then such speakers may be using parrhesia” (115).

In addition, while Foucault argues in “Discourse and Truth” that parrhesia and rhetoric “stand in strong opposition” because parrhesia is the “zero degree of those rhetorical figures which intensify the emotions of the audience” (7), other scholars disagree. Walzer argues that “It would not…be inaccurate to describe rhetoric…as the ‘technical partner’ of parrhesia in the context of the philosophical schools” (Walzer 16). This is because offering “frank criticism” requires considering timing, audience, and circumstances. He quotes Plutarch in saying, “frank criticism is ‘an art,’ a medicine for the soul” (Walzer 17).

Thomas Goodnight further argues that parrhesia “emerges from a communication predicament where, at one and the same time, an arguer is obligated to raise unwelcome claims while preserving a communication space that gives the interlocutor reasons to listen, rather than an excuse to react” (1). Building on Goodnight’s view of parrhesia as the balance between raising difficult truths and preserving open dialogue, Jessica Townsend further characterizes rhetoricians as “political parrhesiastes” who adapt truth-telling to the political and situational nuances of their time (39). She explains: “whereas ethical parrhesia is the frank truth telling of present circumstances to a ruler, rhetoric is that parrhesia which requires a gentler nudge in the direction of truth according to the constraints of the situation at that time” (39). Or, Townsend describes this another way when discussing Plato’s dialogues as an example:

If Socrates at this time had simply told his arguers what was wrong with their reasoning, they would not have been convinced of these truths; they would have called him mad, ignored him altogether, or simply had him indicted of corruption much earlier in life because of such controversial beliefs. Instead, Socrates used a rhetorical line of questioning to gently lead his arguers into their own conclusions so that they applied their own reasoning to discern the truth (39).

This ancient commitment to parrhesia—the courage to speak truth openly for the sake of ethical and intellectual growth toward the common good —echoes through later arguments for freedom of speech several centuries later. In an historically significant speech to the British Parliament called Areopagitica in 1644, John Milton defended the freedom of speech and the press against pre-publication censorship (something we will call “prior restraint” later ), arguing that truth thrives in an environment where ideas can be freely debated and confronted and warning against the dangers of censorship. He said, “the ingenuity of Truth, who when she gets a free and willing hand, opens herself faster than the pace of method and discours[e] can overtake her.” Like the Greeks, Milton sees free speech as a path to wisdom and societal improvement, advocating for an open marketplace of ideas where truth can emerge from the clash of opposing views.

200 years later in 1859, English philosopher John Stuart Mill continued this through-line of argument in Chapter 2 of his treatise On Liberty, in which he wrote about the need for free discourse in the pursuit of truth. Just like Plato’s Socrates professes public discourse should do in Gorgias, Mill writes that “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind” (30). Mill offers several reasons for this assertion. For instance, the censored opinion might be true and the accepted opinion erroneous. By censoring speech, society would deprive itself of “exchanging error for truth” and deny itself of “the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error” (31). Legal scholar Robert Post argues that the understanding of public discourse enshrined in the U.S. Constitution has a similar function as Mill’s maxim because it forbids the state from imposing rules on discourse communities: “to do so would privilege a specific community and prejudice the ability of individuals to persuade other of the need to change it” (632). This is speaking with parrhesia in a modern sense, preventing the government from retaliating against frank speech that might change the doxa. Freedom of thought was for Mill was what dialectic was for Plato – integral for seeking truth and a fundamental to the human condition.

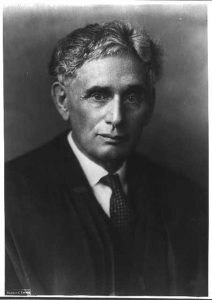

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. used a different metaphor for this philosophy in his dissent in one of the first free speech cases to reach the Court in 1919, Abrams v. United States. Holmes, with Justice Brandeis concurring, wrote, “But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas, that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market” (Abrams v. United States 630). Holmes roots his concept of freedom in a specific tradition of economics that viewed competition as a driving force that encourages participants to prioritize goods (or ideas) based on their perceived value. In his view, such competition would naturally lead to informed choices. Holmes’ metaphor of the “marketplace of ideas” is the most widely cited metaphors First Amendment theory and remains a potent argument for advocating for open discourse well into the 21st century.

Historical Reasons

“Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech and assembly. Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears,” wrote Justice Louis Brandeis in a concurrence in the case Whitney v. California. He went on, “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence” (376). When Justice Brandeis wrote these words, it was 1927, and the Supreme Court was still leaning more toward censorship of political speech than away from it. Brandeis’ words, however, would foreshadow what would eventually become the guiding principles of our First Amendment philosophy today. By making ideas and knowledge accessible to anyone and everyone, people may feel empowered to engage in discourse and, in theory, use reason and sound judgment to improve society.

While a free exchange of discourse may allow a person or public to develop epistemological understanding – or to know how they know what they know – protections upon freedom of expression preserve the ability to continuously achieve such understandings. Even this, however, cannot happen without a space for free discourse. As Cicero insinuated in Rhetorica ad Herennium, speakers should seek to move their hearers. However, audiences cannot be moved unless they have the freedom of thought to consider the message, which is only possible if the speaker has isegoria (and specifically the legal protection against government retaliation for speech) and/or embodied ability to speak their mind; to speak with parrhesia. The sentencing of Galileo Galilei is a well-known example of what happens when such rights are not protected. Charged with heresy during the Spanish Inquisition, Galileo was found guilty of teaching and defending the Copernican doctrine of a heliocentric universe, in which the earth moves around the sun, presumed to exist at the universe’s center. In what was in actuality a trial of truth v. power, Galileo was subsequently forced to live the rest of his life on house arrest (Galileo Galilei). To ensure that speech is free, people must be guaranteed the ability to seek knowledge without fear of retribution, to have opinions without fear of persecution, and to engage in public discourse without fear of those in power.

Thinkers from Plato to Justice Holmes privileged the notion that the freedom to exchange ideas is necessary for knowledge to develop, communities to be just, and people to grow. Authoritarian leaders, however, fear that an educated populace might question decision-making, criticize actions, and discover corruption. There is a risk that an educated citizenry, especially one provided with information via a free press, might decide through public discourse that it wants a change in leadership. Providing the protections of freedom of speech, assembly, and the press that provide for parrhesia and isegoria empowers the people, a prospect that may be formidable and less than ideal for those with authoritarian tendencies. This is indeed why when authoritarian regimes rise to power, institutions like universities and the press are often the first to be shuttered. The New York Times Editorial Board wrote about this in March, 2025:

“When a political leader wants to move a democracy toward a more authoritarian form of government, he often sets out to undermine independent sources of information and accountability. The leader tries to delegitimize judges, sideline autonomous government agencies and muzzle the media…The weakening of higher education tends to be an important part of this strategy. Academic researchers are supposed to pursue the truth, and budding autocrats recognize that empirical truth can present a threat to their authority.”

This troubling global trend is reflected in the actions of leaders like Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdoğan, who has jailed university professors and political rivals, and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, who has exiled journalists and imprisoned his most prominent political critic, Alexei Navalny—who recently died in prison.

As Mchangama points out, “the ability to criticize freely one’s own political system is still a litmus test of democracies, both past and present” (14). In fact, The United States was on its democratic journey for less than a decade before its government restricted the ability of its citizens to fearlessly criticize government leaders, despite explicit protections for speech in its constitution. President John Adams passed the (1798) Alien and Sedition Acts, one of which made it illegal to “write, print, utter or publish…any false, scandalous and malicious writing…against the government of the United States” (“Alien and Sedition Acts”). Fortunately for him and the nation’s future, President Adams had the foresight to write a sunset clause into The Sedition Act so that it would expire upon his exit from office, lest it be used against him by his political enemies. When he took office on that day, March 4, 1801, the new President, Thomas Jefferson, made reference to the importance of these freedoms in his “First Inaugural Address” when he laid out what he deemed “the essential principles of our Government”:

“Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political; peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none…the preservation of the General Government in its whole constitutional vigor, as the sheet anchor of our peace at home and safety abroad…absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority, the vital principle of republics…the diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason…These principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety.”

Only one of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 remained law — The Alien Enemies Act. This act gives the President wartime power to “apprehend, restrain, secure, and remove,” any all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government,” 14 years of age and older. The act was used during the War of 1812, World Wars I and II, and most recently by President Donald Trump, although because the act can only be used once Congress has officially declared war, Trump’s use of the law is constitutionally questionable and is facing court challenges (Treisman).

When the framers of the U.S. Constitution codified a right to free expression into their new set of laws as the first right protected in a list of civil rights guaranteed to citizens, it was a radical act. For more than a thousand years, monarchial systems of government in the Western world had held sway, refusing to explicitly protect the right of “common people” to openly discuss issues of public importance or be critical of their leaders. This did not mean, though, that people did not want the right to do so.

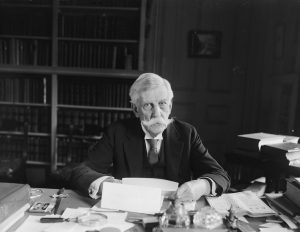

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, known as “the people’s attorney,” Justice Brandeis wrote the following in his concurring opinion in one of the initial landmark First Amendment decisions in the early 20th century:

Those who won our independence…believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government (“About Our Namesake: Louis D. Brandeis”).

What is significant about Brandeis’s statement is his reminder that the United States was the first country to cement free speech into its Constitution and its laws. While free speech does not always lead to thoughtful, responsible discourse, it is essential to democracy and a bulwark against tyranny. In the late 18th-century American colonies, the conditions were right for legal protections upon free speech to resurface, albeit in a contradictory and violent manner. In fact, the first British colonizers to arrive in America forcefully seized land from Indigenous peoples with the explicit purpose of seeking religious freedom. Although England guaranteed the “freedom of speech and debate” in Parliament in the English Bill of Rights, individual British citizens were not allowed to criticize their leaders, as the government considered that “seditious libel.” Ironically, British colonists who sought freedom of religion ultimately limited both religious freedom and freedom of speech by establishing governments that mimicked this top-down monarchial system. They made the head of the church and the head of the town synonymous, while also imposing their “Puritan” religious standards on the Indigenous people they colonized.

The years preceding the American Revolution, however, emphasized the necessity of criticizing one’s government and having a say in its policies. Lacking representation in the British government, colonists were subjected to a series of taxes that they opposed but had no standing to contest. Perhaps of most symbolic significance for the freedom of expression, The Stamp Act of 1765 imposed a tax on printed materials, including newspapers and documents. By requiring that any printed material appear on taxed, stamped paper, the Act literally demanded that subjects of British law pay for their right to freely circulate information.

Following boycotts and protests, the British colonial government passed a series of punitive measures in 1774 called The Intolerable Acts, which closed Boston Harbor and altered the Massachusetts colonial government. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson levied the criticism that the colonists could not criticize their government. Neither able to protest or boycott without persecution, they could not speak against government policy, had no access to political representation, and could not even communicate without payment. It is clear, then, why the freedoms protected in the First Amendment appear first in the top of the Bill of Rights.

Part 2: Freedom of Speech and the First Amendment

The Five Freedoms in the First Amendment

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Religion

The first freedom is known as the “free exercise clause,” and states that the government cannot establish a law that dictates how Americans practice religion nor what religion they practice. Additionally, the government cannot establish a “state” religion.

Speech

The speech protected means more than simply spoken or written speech. It has been extended to mean “expression” in the broadest sense of the term. Symbolic action, art, nonverbal communication, creativity, film, speech on the internet, music, inventions, and even pornography have all been types of “speech” added to the protections of the First Amendment over the years. In fact, the crux of most First Amendment debates center around this question: does the expression in question fall into the category of protected “speech”?

Press

The press is the only industry that has explicit protections in the constitution, and it is for the reasons established in the first section. An independent press, free from government influence, is sometimes referred to as the “4th estate.” A free and independent press provides the people with the information required to be informed so that they can engage in dialectical inquiry. Further, the press keeps democracies functioning. For this reason, authoritarian governments often target independent journalists and support what is often referred to as a “4th branch” of government, or state-run media, to control information and messaging.

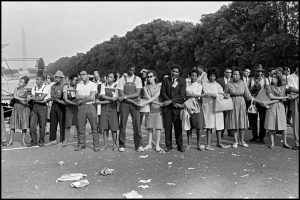

Peaceably Assemble

Protecting the right to of the people to peaceably assemble is another form of expressive conduct and a check on the government, signaling that a group of people share concerns or opinions and care enough to come together to voice them. Throughout history, this right allowed people to come together at political rallies, to form labor unions, and engage in protests and marches.

Petition

The right to petition for a redress of grievances was likely one of the highest on the minds of the Founders because the Declaration of Independence is a petition at its core, yet is one of the least litigated of all of the rights in the First Amendment. Petitioning is a way for the government to hear directly from the people. Arguments can be clearly written out and support can be clearly indicated. Further, the right to petition has been extended to include the right to sue the government to challenge pre existing laws. Petitioning is also a way of participating in the public sphere for marginalized communities when hegemonic cultural dictates keep them out of the public square in other ways. For example, anti-slavery petitions were one of the earliest ways for women to assert their personhood (Zaeske).

“Congress shall make no law…”

Congress refers to the legislative branch of the federal government. Most state constitutions also have protections for the rights outlined in the First Amendment, thus preventing their legislatures from abridging these rights as well. Because the 14th Amendment declares that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside,” the First Amendment’s protections extend to every citizen in the country. Further, the 14th Amendment’s “due process” clause – that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” means that states cannot restrict any rights guaranteed to citizens in the Federal Constitution, including the rights enumerated in the First Amendment. However, even this extension of rights implies that speech and expression by non-citizens remains less protectable by federal law, that such rights may be suspended in times of war, and that private, non-governing entities such as corporations remain able to abridge the rights in the First Amendment. Because the First Amendment only stipulates that Congress shall make no law, and the Constitution only governs actions taken by the state, private entities remain mostly able to act as they choose.

This distinction is important. While U.S. citizens have a right to free expression, they do not necessarily have a right to say what they want (to speak with parrhesia) without facing consequences from other entities besides Congress. For example, an individual could attend a protest at their state capitol, and it would be within their First Amendment right to do so. However, if their company found that in doing so it violated their own policies, that company could be within its rights to fire the individual. The protection of the First Amendment would protect the individual’s right to attend the protest, but does not guarantee that individual’s position or job.

Discussion: Colin Kaepernick Protests Racial Injustice

When then San Francisco 49er’s quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem to bring attention to police brutality and racial injustice, he ignited a national controversy over free speech, patriotism, and civility in public debate (Branch). At the time, President Barack Obama defended Kaepernick’s “constitutional right,” while presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested that, if a player couldn’t stand for the national anthem, that “maybe you shouldn’t be in the country” (Boren). Kaepernick faced major backlash for first sitting and then kneeling during the anthem in protest, facing ire from many around the country. In the clip above, ABC News covers Kaepernick’s continued “protest against racial injustice” on September 13, 2016. Kaepernick kneeled during the national anthem on nationally televised Monday Night Football, along with his teammate, Eric Reid. His other teammate, Eli Harold, raised his fist in solidarity. Kaepernick continued to kneel during the anthem, ultimately inspiring other NFL players and athletes around the world to follow his example. He eventually lost his job and remains out of a job today.

Discussion:

- The First Amendment protects against government censorship, but not necessarily consequences from private employers. Should private institutions like the NFL be expected to uphold similar standards of free expression for their employees? Why or why not?

- How do factors like race, public visibility, and institutional power affect who gets to speak freely without consequence? Would a white athlete have been treated the same way for a similar protest? How does Kaepernick’s protest illustrate the concepts of isegoria and parrhesia?

- Some argue that Kaepernick was “canceled” for his protest. How do we differentiate between a violation of free speech and the social or professional consequences that come from using that speech?

- What lessons can college students and institutions learn from the Kaepernick case about the value and cost of protest? How should universities handle student or faculty protests that are unpopular or politically charged?

The rights of students at public and private schools offers another example. In general, the Supreme Court found that “students and teachers don’t shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate” (Tinker v. Des Moines School District) in public schools because they are funded by and under the jurisdiction of the government, thus falling under the auspices of the phrase “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.”

However, students and teachers at private schools are on private property and receive funding from private entities. Private organizations can enforce a greater set of restrictions upon allowable speech and protest, even as they draw on the government resources such as the police to enforce these restrictions. This is why private schools can enforce prayer in schools, require school uniforms, ban school plays, etc. while their public counterparts, in theory, cannot.

It has been determined, though, that owing to the State’s interest in safeguarding minors and the belief that school officials act in loco parentis (“in the place of a parent”) while children are in school, a slightly greater degree of censorship is sometimes permissible. Over the years, the Supreme Court has decided that public schools can sometimes impose certain restrictions on speech. For instance, public schools can censor lewd speech, the promotion of illegal drug use, and student newspapers (a decision that has also been extended to school-sponsored college newspapers as well) (Bethel School District v. Fraser, Morse v. Frederick, Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, Hosty v. Carter). Conversely, the Court has also found that students cannot be compelled to say the Pledge of Allegiance in school (West Virginia v. Barnette).

Unlike K-12 educational spaces, though, college campuses have long been integral spaces for free speech, serving as bastions of intellectual debate, activism, and the unfettered production of knowledge. Throughout U.S. history, student movements—from the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s to the March for Our Lives against gun violence in the 2010s —have demonstrated the power of speech in shaping public discourse. In general, the Supreme Court has found that First Amendment rights should be protected on college campuses because of the principles stated and academic freedom, allowing institutions of higher education to remain places where diverse viewpoints can be expressed and challenged. However, recent months have seen renewed debates over the boundaries of free speech on college campuses, with conflicts arising over issues such as political protests, controversial speakers, and attempts by the government to regulate expression as many universities try to maintaining inclusive environments.

Example: Protests at Columbia University and other institutions in 2024

Columbia University students representing the Palestinian and Jewish side speak about the campus protests on NBC News in April, 2024. The University had a tumultuous year when in April, pro-Palestinian student protestors set up an encampment on campus protesting the war in Gaza and demanding the University divest from “academic and economic stakes in Israel.”

On that same day, then Columbia University President Nemat Shafik gave a controversial testimony before Congress, prior to returning to campus and calling in law enforcement to arrest the student protestors. More than 100 students were arrested, the largest mass student arrest since protests during the 1960s. The encampment at Columbia inspired similar demonstrations at universities around the country. The tense protest eventually led to the resignation of Shafik and the cancellation of several commencement ceremonies around the country, including at Columbia.

President Donald Trump has brought renewed attention to the demonstrations when ICE arrested Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian graduate student who played a leadership role in some of the protests. Khalil’s wife is a U.S. citizen and he is a permanent U.S. resident with a green card, leading many to call the arrest an attack on his First Amendment rights. Since Khalil’s apprehension, other international students have had their visas revoked or have been detained by ICE officials, some of them seemingly in connection to expression opinions about the Israel-Palestine conflict in newspaper editorials or in protests.

“…abridging the Freedom of Speech…”

The Supreme Court gets to decide what the language in the First Amendment means, including what it means to abridge the right to free speech. According to most legal dictionaries, to abridge means to “diminish” or “reduce in scope.” This is commonly understood to mean that Congress cannot take away a person’s right to free speech, privileging it as a cultural and political value. That is, people should be able to speak freely without fear of government censorship or retaliation – to speak with parrhesia. While many commonly translate parrhesia as “freedom of speech,” Chin-Yu Ginny Lu problematizes that when she writes, “Parrhesia, then, is a quality which a particular act of speech has or lacks. Freedom of speech, on the other hand, is not tied to particular acts of speech, but is rather the possibility of saying whatever you like without government interference or retaliation” (Lu 57).

In the United States, one can challenge a speech restriction by appealing it to the Supreme Court (the judicial branch interprets whether or not a law or conviction violates the clauses in the First Amendment). Cases reach the Supreme Court in a few different ways. One way is if a dispute over a state law reaches a State Supreme Court and is then appealed to the Federal Supreme Court – these cases will have a state as one of the named parties. The Court will hear state issues if they are an issue of national interest or if there are two state laws in conflict with one another. Another way is if a federal law is challenged or violated, and it climbs through the federal court system – these cases will have the “United States” as one of the named parties in the lawsuit. Finally, cases make their way to the Supreme Court via special courts – like when a policy created by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is challenged. Cases usually take a few years to reach the Supreme Court. One of the fastest cases in history from start to finish was a landmark First Amendment decision famously called the “Pentagon Papers” case, which only took 17 days from the first injunction to the Supreme Court decision (New York Times Co. v. United States).

The Two-Tiered Theory of Speech

“The idea of free speech is an eternally radical and counterintuitive one that requires constant education about its principles” (Lukianoff and Perrino). While the idea of protecting the right to “free speech” might seem simple, it is anything but. On one hand, this value supports speaking with parrhesia, which Thomas Goodnight defines as “a figure of thought associated with speaking truth to power” (1). On the other hand, such unrestricted, fearless, parrhesiastic speech can lead to a lack of a collective understanding of facts, values, or knowledge. Foucault points out that this was a concern of Plato when he writes: “The primary danger of liberty and free speech in a democracy is what results when everyone has his own manner of life, his own style of life. For then there can be no common logos, no possible unity, for the city” (“Discourse and Truth,” 32). He also suggests that Plato considers parrhesia “not only as the freedom to say whatever one wishes, but as linked with the freedom to do whatever one wants” (32). Perhaps even more directly, Foucault writes in Fearless Speech, “the parrhesiastes uses the most direct words and forms of expression he can find,” and avoids “any kind of rhetorical form which would veil what he thinks” (12). In American culture and legal jurisprudence, parrhesia as “speaking truth to power” has been a powerful tool for change. Because “speech” itself is hard to define,” though, a modern conception of speaking with parrhesia has allowed for some to interpret it as their right to say what they please without consequence, even if it means spreading hate speech or causes harm.

Typically, the Supreme Court classifies expression protected under the First Amendment into two categories. Justice Frank Murphy wrote in the majority opinion of a 1942 case that there are “certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem.” This type of speech is “of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.” Justice Murphy names these categories as the “lewd and obscene,” the “profane,” “libelous,” the “insulting or fighting words” (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire). This so-called “two-tiered” theory of speech – categorizes some speech as having social value, can bring us a “step toward truth,” and is worth protecting. This speech of social value like political speech, symbolic speech, speech on public issues, speech printed in the free press, etc. The “worthless” speech in the other categories, according to Justice Murphy, is okay to censor. Indeed, the following decades did in fact follow this prescription. For the most part, political speech, symbolic speech, and speech on public issues is protected, allowing for some regulation, assuming it does not restrict viewpoint. Expression that can fit into one of the categories have historically been limited.

Political Speech

“Political” speech is the typically most protected form of expression, but typically for those with socially privileged identities. As Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion in a 2011 case involving the hate group the Westboro Baptist Church, “as a Nation we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate” (Snyder v. Phelps). Aside from the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the U.S. Supreme Court did not hear cases involving the First Amendment until 1919. This was likely because cultural conditions made it so that the freedoms protected in the First Amendment more readily applied to white men. As such, free speech controversies rarely got the attention of the Court. However, at the turn of the 20th century, way of life shifted and those who those who were in positions of privilege found themselves not to be the only voices having an influence in society. The Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented urban growth – and subsequently increased poverty, spurred on by mass immigration, primarily from Eastern Europe. This growth catalyzed new social movements as labor unions formed, workers went on strike, and a new generation of educated women fought for the right to vote. Leaders would literally stand on “soap boxes” to lead rallies.

A key context for the dramatic changes of the early 20th century concerns significant political unrest in Europe and Russia between 1914 and 1917. In 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina in an event widely regarded as the inaugurating event of World War I. In 1917, Tsar Nicholas II and his family were deposed and subsequently killed in a series of events broadly labeled the Bolshevik Revolution. There was political upheaval in the U.S., too, as third parties like the Populists and the Socialists gained political power. President McKinley was assassinated by anarchist Leon Czolgosz, who claimed he was motivated by the words of Emma Goldman, a well-known anarchist, activist, and writer.

Under these conditions, the U.S. passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, despite the fact that political speech was valued as primary. This was, as the history suggests, no doubt a result of classism born from the progressive wins of the labor movement and antisemitism driven by the success of the Bolshevik Revolution. The Espionage Act, which remains law today, is directed at acts of sabotage and protection of military secrets, whereas the Sedition Acts, repealed by the government in 1921, was aimed at censoring those who spoke out against the war effort. There were more than 2,000 prosecutions brought during the years 1917 and 1918. The first free speech case to reach the Supreme Court involved Charles T. Schenck, the general secretary of the Socialist Party. The Party attempted to mail 15,000 leaflets to thousands of Americans who had been drafted, encouraging them to assert their rights, avoid the draft, and join the Socialist Party. Schenck was convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison, and the Supreme Court unanimously upheld his conviction.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the majority opinion in this case, penning what is now a well-known phrase: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Holmes also established the “clear and present danger” test for political speech, stating that speech should be allowed under the First Amendment unless it is “of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent (Schenck v. United States). Prominent Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs was also arrested and convicted for violating the Espionage Act and similarly found guilty of violating the clear and present danger test that same year. He ran for President from jail in 1920.

It was not until culture, context, and the makeup of the Court itself changed decades later that the protections for political speech broadened. The year was 1969, and the country was in an era of social movement and protest. The Civil Rights movement been prominent for over a decade, the second wave of feminism gave rise to a new woman’s movement, the Stonewall uprising gave birth to the LGBTQ+ rights movement, and a massive anti-war movement dominated the country. It seemed as if many historically marginalized communities were using their voices to participate in debate on public issues in greater numbers than ever before, placing greater and broader value on political speech.

It is within this context that the Supreme Court heard the case of Clarence Brandenburg, a leader in the Ku Klux Klan white supremacist hate group. The case of Brandenburg v. Ohio expanded the test for censoring political speech from whether it poses a “clear and present danger” to whether it is likely to incite or produce “imminent lawless action” (Brandenburg v. Ohio). In other words, unless it can be shown that an individual’s words directly and immediately caused action that was illegal, speech is allowable. Because causation is difficult to prove outside of scientific experimentation, this standard makes it so that almost all political speech is allowed in today’s public sphere.

Most recently, the “incitement test” established in the Brandenburg case was applied in the Articles of Impeachment filed against former President Donald Trump following the Jan. 6, 2021 riots at the U.S. Capitol. Filed in the Senate, House Resolution 24 Article I bears the title “Incitement of Insurrection,” and states that former President Trump:

willfully made statements that, in context, encouraged—and foreseeably resulted in—lawless action at the Capitol, such as: “if you don’t fight like hell you’re not going to have a country anymore”. Thus incited by President Trump, members of the crowd he had addressed, in an attempt to, among other objectives, interfere with the Joint Session’s solemn constitutional duty to certify the results of the 2020 Presidential election, unlawfully breached and vandalized the Capitol, injured and killed law enforcement personnel, menaced Members of Congress, the Vice President, and Congressional personnel, and engaged in other violent, deadly, destructive, and seditious acts. (H.Res.24 – Impeaching Donald John Trump, President of the United States, for high crimes and misdemeanors).

Although the U.S. House of Representatives impeached Former President Donald Trump, there were not enough votes in the U.S. Senate to remove him from office. He has not been officially charged with the crime of incitement. However, hundreds of individuals who participated in the riots at the Capitol have been charged with crimes, including some with seditious conspiracy (Habeshian). When he took office in 2025, President Trump pardoned or commuted the sentences of approximately 1,500 people who were charged in connection with January 6.

Symbolic Speech

Political speech has since been expanded to include expression beyond just words. “Speech plus” is a concept that considers speech as an attribute that is paired with one’s conduct and is generally considered to have less protection because it can sometimes lead to other actions or have other consequences. For example, a person cannot burn their draft card, because a person’s draft card serves a function for the government – it is a form of I.D. required of Americans to report if their draft number is called, etc. (United States v. O’Brien). So, while the symbolism of burning one’s draft card might make a statement, the conduct does damage to something that serves a function. On the other hand, one can burn a U.S. flag because of the power of the symbolic expression. Here is Justice William J. Brennan from the majority opinion in Texas v. Johnson, they key flag burning decision in 1989:

“If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable…We can imagine no more appropriate response to burning a flag than waving one’s own, no better way to counter a flag burner’s message than by saluting the flag that burns, no surer means of preserving the dignity even of the flag that burned than by—as one witness here did—according its remains a respectful burial. We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents” (414, 420).

Congress attempted to pass a law banning flag burning after the Supreme Court ruled it protected speech, however the law did not withstand constitutional scrutiny (United States v. Eichman, 1990).

Speech cannot be banned just because someone might find it offensive. As Justice Harlan wrote in a case involving a man walking through a courthouse wearing a jacket with the words “F*** the Draft” on it, “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric” (Cohen v. California). In order to justify a speech restriction, the government must satisfy something called the strict scrutiny test. It is the highest form of judicial review because the rights protected in the First Amendment are considered so paramount. In most cases, the government must prove that any restriction of a right laid out in the First Amendment is narrowly tailored, serves a compelling governmental interest, and is the least restrictive way of achieving that interest.

“…or of the press…”

The Supreme Court has established that the free press should be free from what is called “prior restraint” upon publication (Near v. Minnesota). That is because it is believed that a free press is necessary to hold the government accountable and to protect against authoritarianism and the abuse of power. Further, the free press contributes to public discourse by keeping its participants informed and by fostering continued dialogue. The case that solidified those protections involved the New York Times and the Washington Post. Both newspapers published a stolen classified study of the Vietnam War known as “The Pentagon Papers.”

The study was stolen by whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, acting with what he would likely view as parrhesia, and leaked to the press. Ellsberg was eventually charged with violating the Espionage Act, although he was never convicted due to a mistrial. Every single Justice wrote an opinion in the case, six in the majority and three dissenting. As Justice Hugo Black wrote in his opinion, “In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors” (New York Times Co. v. United States).

Exercise

- Watch: “The Post,” a dramatization of the Washington Post’s decision to publish the Pentagon Papers by editor Ben Bradley (Tom Hanks) and trailblazing publisher Katharine Graham (Meryl Streep) and the landmark Supreme Court decision that followed.

- Read all the per curiam decision and all 9 concurrences and dissents in New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) (decided together with United States v. Washington Post Co. et al.). Do the following:

- Analyze each for how the justices theorize about the balance between the freedom of the press and national security.

- Analyze the justices’ rhetorical strategies, considering tone, appeals to authority, use of precedent, emotion, or historical references

- Reflect on what the case can teach us about the limits free speech and a free press and/or how the case can speak to current debates about freedom of information, whistleblowers, government transparency, or media responsibility.

There have been other well-known attempts to get classified information to the public in the name of informing the citizenry, including Wikileaks and Edward Snowden, who is currently in exile in Russia. It is generally understood that journalists have what is called “qualified immunity” when it comes to protecting their sources, which means that they only need to divulge who their source is if the government can prove that there is a compelling reason why they need the information, that they cannot get the information they need in another way less offensive to the First Amendment, and that the information is clearly relevant to the case. The most famous anonymous source was “Deep Throat,” who gave Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post the information that exposed the Watergate scandal, leading to President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

The role that a free press plays in a democracy demonstrates another lens through which we can understand parrhesia. Ronald Walter Greene, Daniel Horvath, and Larry Browning write about parrhesia as it relates to whistleblowing, writing: “Parrhesia’s constitutive elements – truth, frankness, criticism, danger, courage, duty, and freedom – are useful for describing the rhetorical interventions of outspoken critics of oppressive regimes, conscientious objectors, national-security leakers, and corporate whistleblowers” (39). This type of speaking truth to power is not without its risk for the whistleblower, but the United States has for the most part protected the right of the press to report the information. This potentially allows for even bolder parrhesiastes, who might be willing to take the risk knowing either their identity will be protected or the journalist will feel safe publishing the information in this environment (whereas in other countries around the world, these protections don’t exist).

The Libelous

Just as Plato was concerned about the need for truth in rhetoric, society also values truth and ethics in its reporting. Parrhesia was generally understood in the ancient world to be a way of speaking truthfully, or, at the very least, “whose aim is to reveal the truth” (Lu 58). Foucault traces the transformation of parrhesia in his “Discourse and Truth” lectures as a “personal feature of the ethical or moral character” (33). Aristotle, for example, “prefers aletheia to doxa, truth to opinion. He does not like flatterers…He uses parrhesia to speak the truth because he is able to recognize the faults of others: he is conscious of his own difference from them, of his own superiority” (34). Arthur Walzer observes a similar pattern when he writes about parrhesia from Plutarch’s understanding of it as “the language of friendship” (17). While the press has license to write what they please, individuals do have legal recourse to sue agents of the press if they print false information or violate privacy protections – suggesting a cultural value on the ethical dimensions of parrhesia today. Suing the press or an individual for defamation, sometimes known as libel, is one of the more common free speech lawsuits.

There are four burdens of proof a person needs to demonstrate to prove they were defamed. First, they need to show that the false statement (truth is a defense in a defamation suit) was “published” or that it was a statement made to a third party. Second, they need to prove that they were indeed “identified” in the statement, either directly or indirectly. Third, they need to prove that the statement legitimately harmed their reputation – that it “defamed” them. Some statements that might harm someone’s reputation are things like accusing someone of having a communicable disease, claiming someone committed a crime, saying something that would damage someone’s standing in their community, or saying something that would harm their professional reputation.

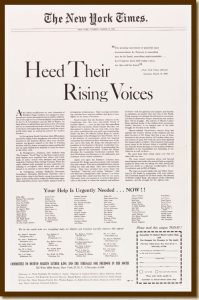

Finally, they need to prove “fault” or that the statement was made carelessly. For private individuals who do not have the ability to exchange allegedly false information for true information, they sometimes only need to prove that the statement was made negligently (it varies by state law). However, public officials and figures need to demonstrate that the statement was made with “knowledge that it was false” or with “reckless disregard for whether it was false or not” (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan). In other words, the person making the claim had to know what they were saying wasn’t true or did not try to determine its validity. This “fault” burden makes it almost impossible for public figures to win defamation lawsuits because it is very hard to prove the intent or mindset behind the making of a claim.

High-profile defamation lawsuits often receive media attention. In Gollea v. Gawker (2013), one of the most impactful cases, professional wrestler Hulk Hogan (real name Terry Gene Bollea) sued Gawker media for posting a sex tape of him. He won that lawsuit and it led to Gawker media filing for bankruptcy. Other celebrity defamation suits have also captured the public attention – like actor Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation lawsuit. Both have been made into Netflix documentaries. In 2023, Dominion Voting Systems won a series of legal victories against Fox News Broadcasting Systems and other individuals for claims made by former President Trump and his partners on their programs about election fraud during the 2020 presidential election. Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani recently lost a defamation lawsuit against two election workers in Georgia for a related incident. In January 2024, former President Trump was ordered to pay damages in a defamation lawsuit filed by writer E. Jean Carroll related to a legal battle involving the sexual assault allegations against him. She filed the suit against him for claiming that she lied when she accused him of the assault. One of the largest amounts of damages ever awarded in a defamation lawsuit was to the families of the Sandy Hook Elementary Shooting victims when they sued YouTube personality Alex Jones for defamation for claiming that the shooting was a hoax. The families have won multiple lawsuits in several states and were awarded damages amounting to billions of dollars.

Watch This Next

Documentary films on defamation cases:

- Nobody Speak: Trials of a Free Press is a 2017 Netflix documentary that looks at the influence of wealthy individuals and potential threats to press freedom through the case of Hulk Hogan v. Gawker. Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press. Directed by Brian Knappenberger. Netflix. 2017.

- Depp v. Heard is a three-part documentary series that examines the 2022 defamation trial between Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, presenting their testimonies side by side and exploring the extensive social media attention surrounding the case. Depp v. Heard. Directed by Emma Cooper. United Kingdom: Channel 4. 2023.

- The Truth v. Alex Jones is a documentary that chronicles the defamation lawsuits brought by the families of Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting victims against conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, highlighting his dissemination of false claims and the resulting legal battles. The Truth v. Alex Jones. Directed by Dan Reed. HBO Documentary Films, 2024.

Written Assignment

Defamation in the Headlines: Applying the Four Burdens of Proof

Part 3: Exclusion, Advocacy, and Resistance

…”or the right of the people to peaceably assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Structural Exclusions

In order to even participate in the public sphere, though, one has to have access. As has been the case for thousands of years, initially, the rights protected under the First Amendment only extended to white, wealthy, male citizens. According to the first census ever taken in 1790, approximately 20% of the population (free white males over the age of 16, as they were counted) – actually enjoyed the right to free expression (Decennial Census Official Publications).

Neither slaves nor free Black men had a right to free speech. It was illegal in most southern states to even teach slaves to read or write for the very reasons outlined above – an educated populace threatens those in power. Slave codes prevented African Americans from assembling or communicating at all. After the Civil War, Reconstruction-era Jim Crow laws imposed restrictions upon newly freed African Americans that denied the rights of free expression in similar ways. The broader system of racial segregation prevented Black people from assembling in public spaces and limited their ability to engage in public life. Limited access to public education and inferior funding led to institutionalized and hindered educational improvement, which in turn contributed to limited economic opportunities. Voter suppression laws limited their political expression and the constant fear of retaliation, often in the form of lynching, for speaking out against systemic injustices made access to the right of freedom of expression all but non-existent.

The right also did not apply non-citizens nor the Indigenous population, nor did it apply to women, who under the system of coverture had no legal identity. A woman, it was believed, could “speak” through the men closest to her in her life – whether that be her father, husband, or another close male relative. This applied to expressing her political beliefs through voting, making financial decisions, making decisions about her household, and even expression of her body, as marital rape did not become officially illegal in the last state until as late as 1993.

Further, many believed that white women’s sensibilities were too delicate for “raucous” public sphere, fearing that their perceived moral purity would be corrupted. As a result, they were relegated to the private, domestic sphere and not permitted to freely assemble like their white male counterparts. Many even believed that women were simply not as intelligent as men. In the 1860s, the French physician and anatomist Paul Broca wrote that “we must not forget that women are, on the average, a little less intelligent than men, a difference which we should not exaggerate but which is, nonetheless, real. We are therefore permitted to suppose that the relatively small size of the female brain depends in part upon her physical inferiority and in part upon her intellectual inferiority.” Women were not allowed to be educated or pursue a career. White women could not even participate in the democratic process through voting until 1920, 130 years after the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

There is perhaps no category that has been censored more broadly than obscene speech, and it has been used as a way to silence women’s voices for over 150 years. Concerns about “immoral,” blasphemous, indecent, and similar types of speech have a long history in our country that affects parts of culture outside of issues of free expression. While this story dates back thousands of years and appears in Greek myths, the Bible, and even fairy tales, at least in the 19th century, this story begins with a man named Anthony Comstock. Comstock made it his mission to target what he believed to be “immoral” speech circulating society, primarily seeking to suppress speech related to birth control, sex education, and obscenity. He was a key player in the passage of the Comstock Act of 1873, which makes it illegal to send “obscene” materials through the U.S. Postal Service.

After its passage, he became a vigilante as a post office agent, particularly targeting birth control advocates. Many famous historical figures were jailed under the Comstock Act, including Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, who was exiled to Europe. Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for President and the first woman stockbroker on Wall Street was also jailed under the Comstock Act for writing a newspaper column alleging that one of her political opponents engaged in an extramarital affair. The Comstock Act is still in effect today and is suddenly relevant again in a post-Roe v. Wade world (Bazelon). It is being used as justification for outlawing the mailing of Mifepristone across state lines, an FDA approved medication abortion pill (“The Threat to Abortion Rights You Haven’t Heard Of”).

Until 1957, the U.S. operated with a broad understanding of what obscenity meant and many books, including works like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, were banned under its umbrella. Once, a book publisher named Samuel Roth published unauthorized copies of these works and another obscene book called American Aphrodite before he was charged with violating the Comstock Act for sending circulars about the books through the mail. As such, the Supreme Court revisited the definition of “obscene speech” in 1957 (Roth v. United States). They further expanded the definition in 1973 and settled on the definition still used today (Miller v. California). For speech to be illegal, it must be considered based on “whether the average person applying contemporary community standards would find the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest.”

Average person is meant to refer to a general category of reasonable person. However, even this idea is complex. As feminist thinker feminist Catherine MacKinnon points out, the average person standard on which obscenity law is built is based on a pornography industry built around male standards of morality that doesn’t consider harm to women (Franks 50-51). Prurient means having an excessive or unwholesome sexual interest. Further, the work must depict or describe in a “patently offensive way,” “sexual conduct” as specifically defined by the law in the state in which the speech is uttered. Finally, it has to violate the SLAPS test – it has to lack Serious Literary, Artistic, Political, or Scientific value (Miller v. California). In a modern, contemporary context, the work must describe sexual conduct as specifically defined by state law, and it cannot pass the SLAPS test. It is for this reason that things like sex education books (scientific value), pornographic films (artistic value), and erotica (literary value) are now no longer categories of speech that can be censored.

The other realm of speech that it has been considered permissible to limit is speech that is harmful to children. Child pornography is considered unprotected speech because of the harm it does to the minors who might be involved in making it and who might be triggered emotionally by seeing it (New York v. Ferber). Another example of protecting children from harmful speech concerns the restriction of lewd or profane speech on broadcast mediums as regulated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The Supreme Court determined in 1978 that it is within the regulatory power of the FCC to restrict certain language and content on broadcast airwaves because the broadcast medium is uniquely pervasive and accessible to children (FCC v. Pacifica Foundation).

This is also the justification that the government first used when seeking to regulate Internet content. As part of the vast Telecommunications Act of 1996, Congress attempted to pass the Communications Decency Act, prohibiting indecent or obscene content on the Internet. The Supreme Court found it overly broad and vague, as it did other attempts to regulate Internet content (Reno v. ACLU). The Court has only been satisfied with attempts to regulate the Internet when they align with the regulation of political speech, specifically focusing on Time, Place, and Manner restrictions. The Court determined it permissible to require libraries and schools to install filtering software to prevent minors from accessing inappropriate material (United States v. American Library Assn., Inc.). That way, if an adult wanted to have the filter removed, they could.

The LGBTQ+ population is another historically marginalized group who has been denied a right to free expression and, while progress has been made, is still fighting against prejudice and censorship today. For centuries, LGTBQ+ individuals have been unable to live as their authentic selves, which a form of censorship in and of itself. Today, Republican lawmakers have introduced over 500 bills across the country that aim to restrict LGBTQ+ expression that include things like bans on books and limits on school curricula that teach about gender and sexuality. Florida passed a law that prevents “all employees or contractors in a public K-12 school from providing students with their ‘preferred personal title or pronouns if such personal title or pronouns do not correspond to that person’s sex,’” while at work.

Perhaps the most visible and obvious ban on expression are the bans aimed at “drag queen story hours,” events at which drag queens will visit public libraries to read books to children. Tennessee became the first state to pass legislation that restricts drag shows in public spaces, and many states have bills either pending or passed since. Most legislation argues that the drag queen story hours violate state anti-obscenity statutes. So far, federal judges have found that these bills are unconstitutional and violations of free speech. Judge Thomas Parker, an appointee of former President Donald Trump, went so far as to say that the Tennessee law “targets the viewpoint of gender identity” (Cochrane).

Across the United States, a wave of book bans is disproportionately targeting stories by and about marginalized groups. Many of the banned books center on race, gender identity, and sexuality—topics that some view as controversial but are vital to inclusive education and representation. These bans amount to a form of censorship that silences diverse voices and limits students’ access to the full exploration of knowledge.

For those in privileged groups, though, they often need only contend with structures and systems when wanting to express their political viewpoint. The only regulation the Court has in theory put on “political” speech relates to what are referred to as Time, Place, and Manner restrictions. These restrictions give the government the power to regulate the when, where, and how of speech for purposes of order and public safety. Such restrictions must also be “content-neutral” and made in a “non-discriminatory” manner. In other words, a city can charge an organization a fee to stage a parade because of the costs to law enforcement, street clean-up, etc. They must also charge the same fee to other groups and not charge more because they disagree with what they represent.

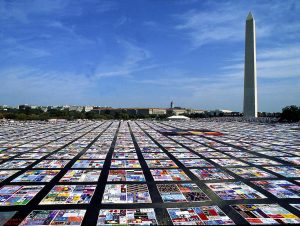

Time, Place, and Manner restrictions are based on the 3-part public forum rule – the idea that publicly owned spaces (tax-payer funded spaces run by the government) should be open for public discourse. There are three different types of public forums, though (Perry Educ. Ass’n v. Perry Educators’ Ass’n). A quintessential public forum is a space that is always open for debate and public discourse, such as the grounds of a state capitol, the steps of the Supreme Court, or the National Mall. Some of the country’s most famous protests, marches, and “discussions” have happened in these spaces. A limited purpose public forum is a public forum only when it makes sense as compatible use of the space. An example of this kind of forum is the auditorium of a public high school. During the school day, the space is used for education and should serve the high school students; it is therefore not an open public forum. However, in the evening, a school board or city council meeting could open this space for use as a public forum. The third type is a non-public forum – spaces that are owned by the government but never open as spaces for public discourse – such as the Oval Office.

These categories do not necessarily account for today’s true space of discourse: cyberspace. The Internet is difficult to regulate because it is not easily delineated in terms of time and space, transcends borders, and is for the most part controlled by private companies. Further, while most of the Communication Decency Act of 1996 was overturned for being overly broad and vague, remains law. Section 230 provides immunity for Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and content platforms for the content posted by users. The rationale for this law is that there is no way for the platforms to control what users post, so if they make a good faith effort to take down threatening content or content that violates intellectual property (something referred to as the “good Samaritan clause”), they cannot be sued for wrongdoing. Section 230 has been controversial, particularly with the rise of social media, as critics of companies like YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook have accused platforms of avoiding accountability for harmful and misleading content.

When members of historically privileged populations have unrestricted access (isegoria) and can speak with parrhesia, it is not uncommon throughout history for that privilege to be abused, sometimes with dire consequences. Adolph Hitler used oratory to convince millions of people to commit heinous crimes, leading to the torture and murder of millions of Jewish people, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, and more. White Europeans used logic and argument based in Christianity and “science” to convince others to enslave and torture Africans. They were successful at persuading others in believing that people of African descent were inferior, and thus justifiably categorized those of African descent as 3/5th of a person in the U.S. Constitution and treated them as less than human in practice. Relatedly, white European men also convinced themselves that they were more superior intellectually than any other race around the world, which led to a centuries-long campaign of colonization and violence around the world. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan held marches to intimidate Black communities in the wake of the Civil War and continue to do so today, most visibly at the “Unite the Right” rally in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia when a car ploughed into a crowd and killed a counter protestor named Heather Heyer.