Chapter 10: Counterpublics

Publics and Counterpublics

Carlos A. Flores and Sarah E. Jones

This chapter focuses on the relationship between theories of the public sphere and rhetorical theory. Engaging in the study of rhetoric requires a thorough understanding of the public sphere, its impact on our understanding of rhetoric, and the crucial role of audiences in this interplay. The first part of this chapter presents a detailed history and foundational definitions of the public sphere. The second part explores critiques and concerns related to the foundational concept of the public sphere, followed by the invaluable theory of counterpublics. Finally, we conclude with a brief illustration of both publics and counterpublics through several contemporary case studies.

Part 1: Defining Publics and Counterpublics

A key entry point to the concept of the public sphere is to envision it as a space of discussion and argumentation, with relative emphasis on audiences. At its core, an argument is a communicative and declarative act with the purpose of changing attitudes and behavior, which is a rudimentary element in public spaces of deliberation and discussion. In their treatment of traditional argumentation concepts, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969) assert that the quality of argumentation is best assessed by examining the audiences that are being addressed. More specifically, in stating that “for all argumentation aims at gaining the adherence of minds, and, by this very fact, assumes the existence of an intellectual contact” (p. 14), Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca establish indispensable ground for the public sphere in terms of audiences needing to come together in order to create and sustain rhetoric. Additionally, Thomas Goodnight’s (1982) concept of “argument spheres” was explicated to clearly situate the expectations of argument for both experts and lay persons. For Goodnight, a sphere of argument symbolizes “branches of activity–the grounds upon which arguments are built and the authorities to which arguers appeal” (p. 200). These three branches– personal, technical, and public– establish the expectations for how arguments should be created and relayed to audiences of various levels of knowledge, expertise, and lived experiences.

These argument centric concepts run parallel to the public sphere’s explicit conceptualization by philosopher-scholar Jürgen Habermas in 1962. As he defined it, the public sphere represents the idea and potential for individuals to discuss issues, topics, and matters of critical debate and importance. In a more tangible sense, a public refers to an audience of individuals (voluntary or involuntary) who are the recipients of rhetorical acts, one act being public opinion. Habermas drew from classical concepts such as the polis and agora (the city-state and the marketplace, respectively) to develop the idea of the public, noting that these are physical places where public activity occurs. However, public activity is not confined to these designated areas, as a public act or event can range from participation in a courtroom to athletic competition. The context or setting of publicness will shape and influence the type of public acts taking place. Habermas (1962) argued that “publicity is the public carrier of public opinion; its function as a critical judge is precisely what makes the public character of proceedings – in court, for instance – meaningful” (p. 2). Therefore, the public sphere is often concerned with decision-making and actionable causes of state-sponsored structures and other institutions responsible for producing and circulating local news.

Based on Habermas’s initial work, it stands to reason that anyone and everyone could participate in public-sustaining activities. However, public participation is much more complex than meets the eye. If Habermas’s initial penning of the public sphere falls in the context of state-sanctioned activity and access to privileged resources (e.g., print news), then it is also reasonable to assume that both barriers and challenges exist to laypersons finding a way to participate. Thus, Habermas’s conceptualization of the public sphere presents important consequences for how we come to understand the communicative and rhetorical acts of argumentation and deliberation, among others. In the following section, we detail some of the affordances and drawbacks of Habermas’s approach.

Affordances and Drawbacks of the Habermasian Conceptualization

In its ideal form, the public sphere is open to all. According to Habermas, this is one of the self-understandings of the public sphere—that there are ample opportunities to become “properly public” (p. 128), and to take part in any activity relevant to the sustenance of a public. Thus, while the public sphere is not a concrete concept, it takes concrete form (in people). In this way, Habermas’s version of the public sphere is explicitly linked to communication. Our understanding of the public sphere through Habermas is also historically situated (both in the past and looking forward) and gives due credence to revolution (Habermas did not endorse the deliberation argument theorists as “what it all boils down to”).

Despite these affordances of Habermas’s principal conceptualization, there are important drawbacks. First, Habermas is thought to have idealized the public sphere by rooting its conceptualization in monarchical states. A necessarily critical perspective reveals that Habermas’s public sphere tends to privilege the act of critical and rational argument by those with access, status, and resources. This begs an important question: Who gets to participate in the public sphere? Scholars including Hegel and Marx challenged Habermas on this level, as did Negt and Kluge (1993). In their chapter, “On the dialectic between the bourgeois and the proletarian public sphere,” Negt and Kluge offered an exposé of the bourgeois ideology that motivated Habermas’s idealization of the public sphere. For Negt and Kluge, the use of dialectic in their work speaks to the use of competing conceptualizations between the aforementioned bourgeois public sphere and its counterpart, the proletariat public sphere. By adopting a Marxist perspective, both authors argue that focusing on the ideology of the public sphere is, in actuality, a distraction from actual material conditions. Whereas the interests of those in the bourgeois public sphere are given more focus and implementation, the interests of those belonging to the proletariat public sphere are only made knowable if they are brought to the forefront as “living labor power” (p. 57). Among other trenchant critiques, they also challenge the degree to which the bourgeois order can be held “in check”—”It cannot significantly be held in check by any separation of powers or procedural rules during the political implementation of the bourgeois order’” (p. 54).

A second (but related) drawback of Habermas’s conceptualization lies in its discursive framing. Habermas’s conceptualization of the public sphere relies on colonial language but says little about colonialism itself. Marx, for example, would argue that it is a delusion to think one can stand in for all of humanity as a classed individual; that we ought to consider, “Who has the leisure time to become literate, to think, to take a horse and carriage to the coffeehouse…?” Put differently, someone is making the products being bought, someone else’s labor is going on, and someone does not have the time to go to the coffeehouses or be invited to the salons. But because coffee was this thing and coffeehouses were places—both symbols of empire–their existence and our participation came out of forced labor. As a result, scholars have critiqued Habermas’ writing of the emergence of the public sphere for its failure to note how it was, at least in part, permissible because of plunder and forced labor.

Third, while Habermas was instrumental in conceptualizing the public sphere as a site for deliberation and for the changing social worlds and imaginaries (starting from print media), the existence of historically and geopolitically specific events and institutions made continued reliance on Habermas’s conceptualization difficult. This led to scholars “re-introducing” public sphere theory—“recast[ing] the public sphere in light of global changes that have reorganized relations between nation-states and their peoples” (Bell, 2007, p. 2). In the following subsection, we explore other scholars who have problematized the public sphere, how it is constituted, and whose participation is awarded.

Beyond Habermas

John Dewey’s “The Public and Its Problems” (published four decades before Habermas and, perhaps consequently, less attributed) offers an equally compelling and arguably more flexible articulation of the public sphere. Dewey’s model of the public sphere is dynamic and emerges from the ground up, in contrast to Habermas’s view of the public sphere, which is more focused on institutions. At any time, we have multiple publics at different stages of intensity, duration, and population, all different and in motion. A “public” can emerge around very different issues using this formula. Thus, “the public” is a concept—a sense of collectivity that has a lot of problems—and those publics self-articulate around various social issues. Where does “the state” come into play? The state emerges when the public organizes itself and forms systems of governance and formal positions, including officers. Thinking of this emergence in the form of an equation can be heuristically helpful (though admittedly a bit reductive):

the state = the public + government/organization/regulation/officers

Dewey’s model is especially helpful for understanding the state’s place within public sphere theory. If the government is a material organization of the public (meaning, governance is a scalable principle of self-organization), then it is clear that the state is not a goal, but a material outcome and consequence emanating from the myriad activities undertaken by both the public and institutionally affiliated persons. This builds off the argument by Greene (1998), who posited that “an articulation of a governing apparatus requires that particular behaviors and populations become visible so that a program of action can intervene to improve the happiness, longevity, and material welfare of a population” (p. 31). The ongoing actualization of the state, which is brought about by said populations and representatives of governing apparatuses, must be given careful attention when theorizing how the public sphere can be further imagined in our contemporary societies. In the video below, Noam Chomsky (considered a founder of modern linguistics) discusses John Dewey’s ideas of a democratic society. Dewey is referenced numerous times in Chomsky’s 2000 book, Mis-Education.

In addition to Dewey’s treatise on the public sphere, scholars such as Lauren Berlant, Nancy Fraser, and Michael Warner have offered invaluable extensions to our understanding of the public sphere and its scope for the citizens it seemingly represents. As a critical and political theorist, Berlant (1997) posited that many of the issues rooted in discourses of citizenship and belonging in the United States (U.S.) point to the fact that the “political public sphere has become an intimate public sphere” (p. 4). She cemented this claim further by comparing the notion of an “intimate” public sphere in the present day U.S. to the intimate, bourgeois-laden conceptualization coined by Habermas. She argued, “the intimate public sphere of the U.S. present tense renders citizenship as a condition of social membership produced by personal acts and values” (p. 5). More specifically, the social practices and values enacted within intimate and private settings are necessary preconditions for participating in the public sphere. This, and many of the other claims Berlant offers are within the context of Ronald Reagan’s presidential administration, further animating Berlant’s expansion of the scope that public sphere theory can capture.

Following a trajectory similar to that of Berlant, Nancy Fraser, a critical theorist, also pushed the bounds of public sphere theory. She took particular issue with Habermas’s idealized version of the public sphere–how it excluded individuals from participating in public activity if they lacked access to resources, status, and power in the public broadly. Rhetoric and public sphere scholars generally take care to label this version of the public sphere, as made by Habermas, the “bourgeois public sphere.” In her 1992 chapter titled “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” Fraser argued that past iterations of the public sphere were not only bourgeois but also masculinist and needed to undergo “some critical interrogation and reconstruction if it is to yield a category capable of theorizing the limits of actually existing democracy” (p. 111). To that end, Fraser offered a fresh set of truths about the consequences and opportunities of the public sphere: (1) the public sphere requires participants to set aside (or bracket) their varied statuses to be considered “equal” participants in the public; (2) having multiple publics is detrimental (not beneficial) to democracy, as others have argued; (3) only matters of public (not private) interest should benefit the common good; and (4) a fully working public sphere necessitates a separation between society and the state (pp. 117-118).

Fraser’s expansion of public sphere theory highlights how those who aspire to be included in the public are marginalized from Habermas’s original conceptual model of the public sphere (through formal and informal impediments) and are thereby excluded from being part of the public (leading to ostracization and broader social inequity). Indeed, it is a lofty assumption that two or more interlocutors can and should set aside their statuses and positions of influence to be deemed as participants on equal footing in the public when this alleged “bracketing” only serves as a structural obstacle to remind participants (specifically, those with less influence) of the stakes they have in spaces of discussion, deliberation, and action. This bracketing, however, is an all too common feature of what Fraser referred to as “stratified societies” or characteristics “whose basic institutional framework generates unequal social groups in structural relations of dominance and subordination” (p. 122).

Additionally, Michael Warner (2002b) presented a variety of criteria delineating the construction of publics and counterpublics. For the constitution of publics, Warner outlined seven distinct criteria that are indispensable for how we come to imagine the scope and boundaries of publics: (1) publics are self-organized; (2) a public is a relation amongst strangers; (3) the address of public speech is both personal and impersonal; (4) a public is constituted through mere attention; (5) a public is the social space created by the reflexive circulation of discourse; (6) publics act historically according to the temporality of their circulation; and (7) a public is poetic world-making. Taking all of these criteria together, the creation and circulation of publics are best considered in relation to their placements in various social imaginaries, rather than confining them into bounded spaces and places. Warner’s treatment of publics is also accompanied by an examination of how they take on the form of being “counter” or “oppositional,” especially when accounting for what subordinate statuses they carry (Warner, 2002b, p. 86). Given how often said statuses are subsumed in personal identities and histories, both of which are brought to the forefront of modern political affairs, the constructions of publics and counterpublics, as well as the dynamic between public and private matters, are complementary and poignant expansions of Habermas’s public sphere theory.

“Where do we go from here?” one might ask. When those who are strategically and institutionally pushed to the margins of society are not afforded meaningful opportunities to become members of their public spaces and places, we must turn to counterpublics, which seek to define the outlets, resources, and settings for marginalized individuals to convey and communicate their needs and interests in opposition to the forces that attempt to contain them. We will explore this premise in the next section.

Counterpublics

Counterpublics can be thought of as alternative or oppositional publics: publics that perceive themselves to differ significantly from or exist in conflict with the dominant public. (It should be noted, however, that this reference to perception is not without controversy. Robert Asen (2000) argued that we should consider material dynamics when determining a counterpublic because a definition of counterpublic that relies on perception keeps it open to any community who perceives itself as being marginalized.) In addition to Fraser, Warner, and Asen, various other scholars have worked to crystallize the scope of publics and rhetoric broadly and extend the theorizing of counterpublics, including but not limited to: Daniel Brouwer, Karma Chavez, Rita Felski, Gerard Hauser, Kent Ono, Catherine Squires, John Sloop, and Marcia Stephenson. Collectively, these scholars have illustrated how marginalized persons and communities work to be seen as meaningful public agents in contexts such as citizenship and vernacular discourse, both of which help to push the boundaries of theorizing publics and counterpublics in generative and malleable ways.

Features of Counterpublics

We now continue with defining and highlighting the key features of a counterpublic. As shown in the video below, one key feature of counterpublics is that they leverage responses to hegemony (hedge-eh-moh-nee), which refers to the dominance of an idea, ideology, institution, or economic distribution of capital. As explained by Tom Nichols in the video below, the theory of hegemony is often attributed to Antonio Gramsci, whose work has been used to characterize the public sphere as a space defined by hegemony.

Fraser’s conceptualization of counterpublic activity is constructive for understanding the hegemonic dialectic between publics and counterpublics. In her influential 1992 chapter, Fraser framed counterpublics as “parallel discursive arenas” in which members of subordinated social groups “invent and circulate counterdiscourses” which allows them to “formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs” (p. 67). In other words, counterpublics emerge as a response to exclusions of the public sphere (what Fraser referred to as “dominant publics”) and as a result, help “expand discursive space” (something very beneficial in a stratified society). Take late 20th century feminism, for example. According to Fraser,

…feminist women have invented new terms for describing social reality, including ‘sexism,’ ‘the double shift,’ ‘sexual harassment,’ and ‘marital, date, and acquaintance rape.’ Armed with such language, we have recast our needs and identities, thereby reducing, although not eliminating, the extent of our disadvantage in official public spheres.

Counterpublics can be wide in scope and unique in function. A counterpublic may function first as space for retreat or comfort and later, as a vessel for protest. This is what Fraser referred to as the “dual character” of counterpublics in stratified societies. In one sense, counterpublics “function as spaces of withdrawal and regroupment.” In another sense, they also “function as bases and training grounds for agitational activities directed toward wider publics” (p. 68). The dialectic between these two functions, Fraser argued, is precisely where the emancipatory potential of counterpublics resides. Participation in publics and counterpublics are not linear and one-note (e.g., solely protesting), but instead indicative of individuals’ capacity for demonstrating rhetorical action in various ways. The birth of a public also gives way to human agency–the act of picking and choosing what issues one opposes or which counterpublics one joins (Brouwer, 2006; Warner, 2002a). Broadly, a public’s capacity to evince agency paves the way for members to take up a participatory spirit to act in ways that speak to their sustenance and prevalence in malleable and constitutive ways (Campbell, 2005). In turn, this affords them the benefit of participating in multiple publics through strategies and methods that are accessible and meaningful in their own right.

Like Fraser and these other scholars, there are other theoretical perspectives that can help us to understand the communicative dynamics of counterpublics. The video below features Cheris Kramarae, a scholar of women’s studies and communication known for her work with Muted Group Theory. Muted Group Theory originated in the field of anthropology, and posits that marginalized groups are often ‘muted’ in public discourse because there is no language to describe their experiences. In this video, fellow communication scholar, Em Griffin, interviews Kramarae about Muted Group Theory and the function of power in language. The conversation reinforces the significance of Fraser’s notion of counterpublics as “parallel discursive arenas” that “expand discursive space” and reduce disadvantage.

Counterpublics are not inherently synonymous with social movements. However, the two are commonly connected for many reasons. According to Warner (2002b), when a counterpublic turns toward the state and says, “We’re going to engage with you,” it becomes intelligible as a social movement. In other words, a social movement is a counterpublic that addresses the state and may seek recognition in more or less explicit or institutional ways. Recognition of a counterpublic may be legal – for instance, being recognized with rights of citizenship – or refutative – in the sense that the state may acknowledge a counterpublic’s existence but not its legitimacy. As referenced in the previous section, Warner also maintained that publics and counterpublics are not timeless. They can only act “within the temporality of the circulation that gives it existence,” which means that counterpublics’ existence is limited by the circulation of discourse by and about them (p. 68). Finally, although all counterpublics are publics, not all publics are counterpublics. Similarly, all social movements must involve at least one counterpublic, but not every counterpublic will rise to the level of a social movement.

The Limits of ‘Counterpublics’

Given the features of counterpublics reviewed thus far, it would be easy to define counterpublics as composed of certain types of people or constituted through particular events. However, Asen and Brouwer (2001) and Squires (2002) have encouraged caution, arguing instead that the definition of “counterpublics” requires greater conceptual clarity. Asen (2000) has argued for definitional clarity by raising concerns about overly fixing the core terminology of the public sphere and encourages critics to attend to “the discursive qualities of counterpublics when considering how they set themselves against wider publics” (p. 437). If we are trying to determine what deserves the notion of “counterpublic,” then Asen would argue that we should look for a set of dynamics rather than a meticulous set of persons, places, or things.

While warnings about reducing counterpublics to identity (or places or topics, for Asen) represent valid concerns, Stephenson (2002) reminded us in her work on indigenous counterpublic spheres that identity often does matter to counterpublics and can be claimed as a strategic use. Indeed, “counterpublic” can be understood less as a static, noun-like ‘object’ or ‘thing’ and more as an active, verb-like act of identity-making. In Felski’s (1989) essay on the feminist public sphere, she argued that feminism is both a public and a counterpublic with internal, external, and collective functions that are important for identity-making. Internally, it is a space of discursive opposition rooted in shared identity and solidarity in the mutual experience of gender-based oppression and its effects. Externally, its goal is to spread feminist values throughout society. Collectively, the space is rooted in the active social agent—women’s everyday experiences—so overlapping subgroups are coalitional. Also important to Felski’s conceptualization of the feminist public sphere is the claim that no space is free from the influence and power hierarchies imposed by ideological structures. McLaughlin (2004) exemplified this principle when she argued that while feminists have indeed preserved the emancipatory potential of the public sphere, we must push current boundaries and take a more transnational perspective. In other words, we must consider how integrated global spaces shape women’s lives and understand that not everyone has the resources to divide their lives into private and public. McLaughlin felt that the public sphere’s failure to take a transnational perspective was not inherent, but a simple problem of imagination. For example, if the ‘private’ is seen as pre-political, we miss that the private sphere is actually structured by patriarchy; and if we treat this as a problem of imagination, we have the agency to engage it. Whether we exercise our agency to work inside or outside the institution, both are potentially radical.

Much counterpublic theory in the last decade has focused on counterpublics as spaces of retreat and strategizing—for example, Chavez’s (2011) work on counterpublic enclaves and coalitions, calling back to a social movement-based understanding of counterpublics. DeLuca and Peeples (2002) also introduced the concept of “the public screen” to make sense of how mediated and online contexts are conducive in yielding direct, counterpublic practices. Lastly, Jackson and Foucault-Welles’s (2015) work on the 2014 hijacking of the #MyNYPD public relations campaign highlighted the mediated iteration of counterpublics. When we move counterpublics from physical spaces to mediated ones, what does counterpublic activity look like? The viral 2014 #YesAllWomen campaign (a response to #notallmen, a line often used to deflect feminist arguments against misogyny and male violence) is another recent example. In the following section, we offer an extended case study of counterpublic activity grounded in the uniquely American epidemic of school shootings.

Case Study: Counterpublics and the Students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School

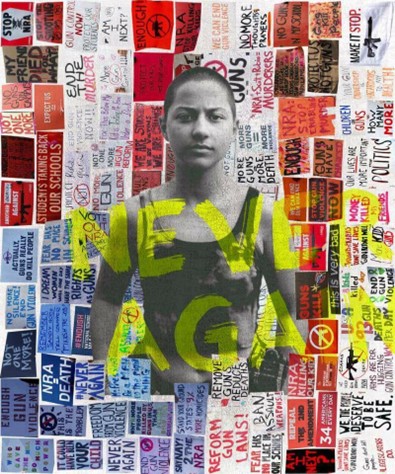

In February 2018, a teenage gunman carried out one of the most stark and tragic mass shootings in U.S. history at the time. Located in Parkland, Florida, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (MSDHS) was the site of a mass shooting in which former student Nikolas Cruz took the lives of 17 people (14 students and three school staff). The shooting sparked national mourning for the lives lost, as well as several demands for action so that future incidents could be prevented at other schools and public places broadly. From this tragedy emerged an organization and movement known as March for Our Lives (MFOL), founded by a small cadre of Parkland survivors who responded to the shooting by demanding concrete changes to gun legislation (March for Our Lives, 2024). MSDHS students X González[1] and David Hogg were thrust into the spotlight through their activism and efforts to challenge the status quo of legislation and policy that led to this mass shooting. González and Hogg were both seniors at the time of the shooting. They rapidly became faces of the movement for stronger gun control legislation, often clashing with elected U.S. officials, members of the National Rifle Association (NRA), and even former President Donald Trump. González is most notably known for delivering a rousing and empowering speech, which is now colloquially known as the “We call BS!” address, a mere three days after the shooting took place. Hogg, in collaboration with González and other high school classmates, also founded the advocacy group Never Again MSD in anticipation of the 2018 midterm elections. The organization aimed to publicly support legislation and political candidates that vehemently opposed the status quo–policies and platforms that directly and indirectly favored gun ownership and a lack of gun control.

Almost six years after this tragic day, González and Hogg graduated from college. As explained in the following subsections, their rhetorical acts (and the Never Again movement writ large) have left a lasting impact on American politics, offering an example of the relationship between the public, counterpublics, and their respective rhetorics.

Youth as “Fighting Their Way into the Public”

As discussed earlier in the chapter, Habermas’s idealization of the public sphere was motivated by bourgeois ideology–it privileged the act of critical and rational argument by those with status, access, and resources. But a public sphere that is contingent on material conditions like a certain class or legal status is limiting in damaging ways. First, it means “the public” will always restrict certain members from attaining elected positions and other forms of full democratic participation. Second, it significantly constrains prospective or aspirational membership by “everyday” people and disadvantaged communities–those folks most likely to be affected by rhetorics and policies of “the state” or state-like apparatuses (e.g., the agora in ancient Greece or the courtroom).

In the case of the Parkland youth, we are intrigued by how their voices have been strategically pushed to the side despite being thrust into the national spotlight. Such a spotlight is often thought of and reserved for older adults and people in positions of influence. Before the mass shooting at MSDHS, these young students did not have access to institutional or formal means of public participation outside of their high school education. Nevertheless, the Parkland youth launched March for Our Lives (MFOL) just one month after the tragedy to energize and mobilize young students to generate meaningful change on the issue of gun violence. Their mission statement affirms this commitment.

Born out of a tragic school shooting, March for Our Lives is a courageous youth-led movement dedicated to promoting civic engagement, education, and direct action by youth to eliminate the epidemic of gun violence (March for Our Lives, 2024).

March for Our Lives (MFOL) led a series of events following the shooting, which allowed it to engage with over two million voting-age youth. The most notable example was the 2018 march on Washington, D.C., which brought out over 70,000 participants and sparked almost 400 auxiliary marches nationwide.

March for Our Lives (MFOL) has also been at the forefront of numerous other initiatives, such as commissioning polling research to gauge young people’s opinions on gun violence issues and legislation and organizing a march in Texas following the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde.

Outside the scope of the formal organization, individual youth have exercised rhetorical agency in their desire to be recognized and seen as members of the public. In his speech at the 2018 march on Washington D.C., David Hogg called attention to the importance of making gun legislation and violence a voting issue:

“When people try to suppress your vote and there are people who stand against you because you are too young, we say no more. When politicians say your voice doesn’t matter because the NRA owns them, we say no more. When politicians send their thoughts and prayers, we say no more. And to those politicians supported by the NRA that allow the continued slaughter of our children and our future, I say get your resumes ready!”

At the core of this speech, Hogg made concerted efforts to encourage young persons (particularly those of voting age) to set their critiques and sights on the very state that strategically chooses to ignore their position as members of a public. By taking elected officials to task and mobilizing young people to engage with the state broadly, Hogg pushed toward the possibility of a democratic society that has long excluded young people.

Hogg’s friend and co-conspirator, X González, is most notable for their prolific “We Call BS!” speech, in which they both allude to the tragedy of the shooting and its effect on young people and take to task state politicians (backgrounded by the U.S. Congress writ large) for allowing laws and conditions around firearm procurement to continue.

González’s ability to be deemed as a legitimate and worthy member of the public is on full display. First, González noted at the start of their speech that they were relying on notes from their AP Government class to deliver their address. Second, González exercised their political knowledge and claim-making abilities throughout the speech–from calling out the NRA’s harmful impact on the political process to calling out former President Donald Trump for repealing an Obama-era regulation that prevented the sale of firearms to persons with mental distress. In short, González positioned themselves as a legitimate political interlocutor and member of the public through their address. Moreover, González demonstrated their agency by pushing back against the state.

In addition to their skill in political rhetoric, González used the speech as an opportunity to reveal young people’s power and potential. In reflecting on the haunting juxtaposition of the day’s events and their involvement in school activities, González declared:

“Instead of worrying about our AP Gov chapter 16 test, we have to be studying our notes to make sure that our arguments based on politics and political history are watertight. The students at this school have been having debates on guns for what feels like our entire lives. AP Gov had about three debates this year. Some discussions on the subject even occurred during the shooting while students were hiding in the closets. The people involved right now, those who were there, those posting, those tweeting, those doing interviews and talking to people, are being listened to for what feels like the very first time about this topic that has come up over 1,000 times in the past four years alone.”

Throughout their public address, González pushed against the perceptions, assumptions, and stereotypes that come with possessing youthful identities. Harkening back to Dewey’s idea of a more dynamic and organic public sphere, we can see that the youth of Parkland and their rhetorical acts are carried out despite (not in complement to) the very state and state-like institutions that have refused to do the necessary work to protect students from school shootings (i.e., contending with the very laws that lead to these events in the first place). The rhetorical acts of the Parkland youth are unique and extraordinary because the victims and survivors were at or just under the age of 18 at the time these events unfolded – the age most often associated with “coming into adulthood” and being afforded adult responsibilities (e.g., voting and enlisting in the military). The youth affected by the shooting can therefore be seen as strategically negotiating their membership to both a public and counterpublic that are complementary to each other. On the one hand, there is membership to a public that is afforded through the aforementioned identity of adulthood. On the other hand, these youth have been thrust into a counterpublic marked by their age and being minimized by more dominant publics for their age and alleged naivete.

In this way, Hogg and González (as well as their youthful colleagues and contemporaries) can be seen as participating in two distinct counterpublics. First, these youth were made to justify their belonging to the public sphere when many individuals and institutions simultaneously downplayed their stances and calls to action, as well as chalked up their displeasures to students’ young age and seemingly not knowing any better. Drawing from Fraser’s (1992) argument of why “bracketed” identities in publics are incommensurate with the conceptualizations of publics that actually exist, these young individuals proved themselves capable of illustrating how the power dynamics between themselves and the very persons and entities they were protesting against were not conducive to a fully representative public sphere. By situating the identity category of “youth” as a counterpublic, we can see how those outside the threshold of adulthood are often regarded by those who think very little of their political and personal agency.

Second, the Parkland youth were at the heart of a counterpublic born out of need, grief, and intimacy in the wake of the mass shooting, reflective of Warner’s (2002b) characterizations of how a public is capable of both self-organization and deeply personal address. This counterpublic has become a significant force and legitimate social movement enmeshed with American politics and the fight towards common sense gun reform. Yet, at the time, this counterpublic was “written off” from the folds of public life due to the fact that many of its members were minors. Both Hogg and González made it a stark point in their public addresses to situate their youth not as an obstacle, but instead as an affordance – one that positioned them as legible and competent members of the publics to which they sought to belong. They pushed for agentic, rhetor-centered discourse and fought to justify their statuses as worthy political participants, despite being written off by detractors. We view this as emblematic of the out-law in vernacular discourse, as articulated by Sloop and Ono (1997). They argued that for out-law discourses, “the logic of the out-law must constantly be searched for, brought forth, given the opportunity to disrupt operating discourses and practices that always work to enable and confine” (p. 66). To that end, both Hogg and González sought to accentuate their youthful status so that publics far and wide could conceptualize, in actuality, that burgeoning members of the public need not hold literal positions of power, have inherited status, or possess access to resplendent resources.

Articulating Counterpublic Complexity and Multiplicity

At a town hall hosted by CNN, the Parkland youth met face-to-face with elected Republican officials and leadership from the NRA, eager and prepared to take these individuals to task for what had happened at MSDHS. González questioned NRA spokesperson, Dana Loesch, on the organization’s position on “bump stock attachments” and the difficulty (or lack thereof) in buying automatic weapons. Cameron Kasky (a junior) challenged Florida Senator, Marco Rubio, to turn down future campaign donations from the NRA. Ryan Deitsch (a senior) vividly narrated his experience doing active shooter drills to Senator Rubio, all while expressing concern that he and other youth have to lead the fight for gun control. The event (and many others following) evidenced how Parkland youth bore the burden of being seen as legitimate members of the public, only to be rejected or minimized in their attempts. While the efforts of these young rhetorical agents have been lauded and acknowledged by many, it is important to situate the scope of their actions within counterpublic theory. As previously described, counterpublics are a necessary extension of the public sphere when the needs, wants, values, and experiences of marginalized persons are not heard or affirmed by those in the dominant public. We can apply this oppositional dynamic inherent to counterpublics to the case of the Parkland youth and their various rhetorical acts. In doing so, we can examine how they accomplished and performed their counterpublicity.

In May 2018, a group of student protesters staged a series of “die-ins” at Publix supermarkets in Florida. The purpose of these die-ins was to publicize the fact that Publix supported gubernatorial candidate, Adam Putnam, who received financial backing from the NRA. Die-ins are a protest strategy dating back as far back as the 1940s, in which people stage a non-violent demonstration in a widely public space to bring attention to an issue of importance. This protest strategy has roots in the Civil Rights Movement, where staging die-ins was used as a key method of voicing one’s opposition to racial violence and force. The strategy is also used to increase awareness and demand that dissenters be seen by the public at large. In the aftermath of the die-ins by Parkland youth, a spokesperson for Publix announced the supermarket chain would temporarily “halt its contributions” to Putnam’s campaign while re-evaluating their plans (Associated Press, 2018, para. 5).

Another rhetorical act was staged when students across the U.S. held school walkouts in the month following the Parkland shooting. Over 3,000 walkouts were held at exactly 10:00 AM and lasted exactly 17 minutes – the 17 minutes a symbolic reference to the exact duration of the shooting at MSDHS. While the time of day and duration of the walkouts were the same across the board, each varied in the dynamic actions performed. Students in Washington, D.C., gathered outside the White House with protest signs and chanted for stricter gun control. Never Again founder David Hogg amplified his message by livestreaming his walkout in Florida. A neighboring school in Parkland, Cooper City High, created an installment featuring 14 student desks and three podiums representing the students and staff whose lives were lost.

As Asen and Brouwer (2001) explained, “counterpublics will differ with regard to density, complexity, breadth, and access to resources and power; they may be episodic, enduring, or abstract” (p. 10). In other words, counterpublics possess a critical flexibility–something unmistakable in this case study of the Parkland youth. Through situations of public dissent and oppositionality, youth both near and far demonstrated their ability to organize as dynamic and malleable counterpublic entities, their ability to go to great lengths to demand validation for a public, and their ability to apprehend the attention of a state that tried to disregard or minimize those attempts at validation. Even to this present day, the youth of Parkland (and the hundreds of other young people who have experienced school shootings and other forms of gun violence) have continued their activism and efforts to challenge the state, ensuring that their counterpublic positioning remains alive and well.

Hogg and Gonzalez

One final line of inquiry in this case study comes from the publicness of both Hogg and González–both rhetorical actors and key faces of the Never Again movement. As delineated below, both rhetors navigated their being catapulted in the varied degrees of publicness in ways distinct to their activist aims and multifaceted identities. Calling back to the argument that publics and counterpublics will vary in their complexity and forms, we argue that the dynamic nature of counterpublics can be extended to individual members of the public, such as Hogg and González.

David Hogg has not been a stranger to the public spotlight following the events of Parkland. Since 2018, he has been at the forefront of different activities and events, including but not limited to publishing the book #Never Again: A New Generation Draws the Line with his sister, Lauren Hogg; being verbally accosted by Georgia Congresswoman, Marjorie Taylor Greene, near the U.S. Capitol; declaring his intent to run for Congress when he reaches the minimum age of 25; and more recently, graduating from Harvard in 2023. Hogg’s engagement with the public can be characterized as active and aggressive towards the persons and entities that seek to discredit him and his validity as a public figure.

Soon after the shooting in 2018, Hogg caught the attention of Fox News host, Laura Ingraham. The host publicly shamed Hogg on Twitter (now known as “X”), making light of the fact that he was rejected from the universities he was most interested in attending: “David Hogg Rejected By Four Colleges To Which He Applied and whines about it. (Dinged by UCLA with a 4.1 GPA…totally predictable given acceptance rates.).” The public call-out drew both attention and criticism from audiences who took issue with a national television host using their platform to shame a young person. However, Hogg did not sit idly by during this attack on his livelihood. Instead, he took to Twitter and called out Ingraham in a message stating: “sooo @ingrahamangle what are your biggest advertisers. Asking for a friend. #BoycottIngramAdverts.” Hogg followed this up with another tweet containing a list of companies that provide advertisements for Ingraham’s show, encouraging his audiences to contact said companies to voice their displeasure over Ingraham’s behavior and demeanor. The list included notable companies such as Hulu, Nestle, Wayfair, AT&T, and Liberty Mutual, among others. Between March 28 (the date Hogg’s initial tweet was circulated) and April 2, 15 companies announced they would remove their advertisements from Ingraham’s show, with some companies offering up pointed PR statements to accompany their action. For example, the spokeswoman for the furniture company Wayfair stated:

“As a company, we support open dialogue and debate on issues. However, the decision of an adult to personally criticize a high school student who has lost his classmates in an unspeakable tragedy is not consistent with our values. We do not plan to continue advertising on this particular program.”

In the heat of the feedback, Ingraham shared a message on Twitter apologizing to Hogg, stating, “Any student should be proud of a 4.2 GPA —incl. @DavidHogg111. On reflection, in the spirit of Holy Week, I apologize for any upset or hurt my tweet caused him or any of the brave victims of Parkland.” Hogg rejected Ingraham’s attempted apology shortly afterward while also reiterating his goal in calling for the advertising boycott. He asserted he would not stop until “you denounce the way your network has treated my friends and I in this fight. It’s time to love thy neighbor, not mudsling at children.” Although this occurrence followed a similar pattern with other Fox News broadcasters (e.g., Sean Hannity and former host Bill O’Reilly) who faced ad boycotts, this was more pointed because Hogg seized upon the public’s support to enact material change and opposition towards a news network and its representative who had systemically denounced young people and their gun control activism. As a rhetorical agent, Hogg demonstrated an uncanny ability to purposefully and meaningfully mobilize the public sphere.

In contrast to Hogg, X González took a completely different trajectory in navigating their surge into the public light. It stands to reason that González became the most immediately recognizable figure of the Never Again movement, particularly for their “We Call BS!” speech and engaging in a debate with NRA representative Dana Loesch, among others. These occasions would be enough to imbue immense pressure on any young person in the aftermath of tragedy. Indeed, González’s account of this aftereffect signals how public and counterpublic activity is not only direct and confrontational but can also be marked by moments of retreat and reflection. In an article written for “The Cut” magazine, X poignantly shared how their involvement with organizing after Parkland fundamentally shaped and altered their current livelihood and their renewed approach to activism, their entry into college being a particular space of change.

X González had expressed an overall desire to distance themselves from the identity with which they were most associated at Parkland and in the early national spotlight. They would soon start their time at New College in Florida, an educational space known to be friendly to queer, trans, and nonbinary students like them. Recounting their initial entry into New College, X said an unnamed individual circulated an e-mail to the student body asking that no one bother X so that X could have a regular college experience. “I still don’t know who did that for me,” X wrote, “but I’m grateful.” As a college student away from the spotlight, X found a life removed from the pressures and expectations of public-facing activism.

Having been the face of a blossoming counterpublic and rising to immediate acclaim, fame, and notoriety, X González spoke from vivid personal experience when they acknowledged that such a trajectory would be overwhelming for any young person. Given that stress and public pressure, X sought to find ways to shed some of their previous identity and come into their own outside of the demanding spaces of Parkland. We find X’s efforts to build a life for themselves outside of their Parkland-rooted activism as symbolic of the critical need for counterpublic participants to engage in rest as a counterpublic act. Indeed, as Fraser (1992) theorized, counterpublics are not unidimensional in character–they can function as spaces of “withdrawal” (retreating) or “regroupment” (strategizing) just as they can also function as spaces for “agitational activities” (protesting). For many, that rest may also bring clarity. In that same article written for “The Cut,” X explained:

“In the queer space of New College, changing your pronouns, name, or presentation is a nonevent. I knew I wanted to go by a different name, something that would give me space and get me away from the identity thrown on TV screens that made people think they knew me. I settled on X (inspired by Malcolm X) and realized in the process that the reason I didn’t like being known as Emma is partially because that person belongs to the public but also partially because it’s such a feminine name. I realized then that I’m nonbinary.”

González’s retreat from the public eye is a profoundly personal rhetorical act. Specifically, their desire to come into an identity wholly separate from the public’s grasp over the name “Emma” was made possible by stepping away from the confines of their public activism. In one of the more pointed turns of the article mentioned above, X shared how they have returned to participating in activism once more, though not directly tied to the issue of gun violence in schools. They recalled how March for Our Lives (MFOL) rallied together for another demonstration to commemorate the anniversary of the shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Their speech at this event was notably more profane than their previous public addresses and signaled a shift in how they see themselves as a rhetorical agent who has come into their own.

“All the other times I’ve given a speech, I’ve kept it PG. But this time, I could not have given less of a shit about seeming like a morally upright person. Me and my friends did everything we were supposed to, and shootings still happen every day. I have nothing to hide or reshape to get my point across. I have a handle on who I am now, and I know how I want to be perceived. The audience was with me. The failure of our government is all too easy to see. We needed to carry our voices over the lawn of the Monument through the halls of Congress and into the ears of our representatives.”

Since the Parkland youths’ ascent into the public sphere, it seems evident that X González’s navigation through that public sphere and all of its pressures has been drastically different from that of their friend and co-conspirator, David Hogg. Both are capable rhetorical actors who have more than proven their capacity for broadly participating in the public. However, González offers an invaluable reminder that public and counterpublic activity need not be linear and direct. Instead, public and counterpublic activity can also be a non-linear, fragmented, and deeply personal experience that expands how we conceptualize and wrestle with the many forms that membership in such collectives can take on.

Part 2: Case Studies in Counterpublic Rhetoric

Below, we offer three additional case studies as prompts in hopes that their examples will sharpen, clarify, and apply concepts during your continued instruction on public sphere theory. Beyond Parkland, other, less-publicized events also reflect meaningful counterpublic resistance. As you read through each of the three additional case studies below, consider the following: How do these spaces constitute counterpublics? What systematic disruption of the public occurred? To what extent did youth in these spaces successfully apprehend and sustain the attention of the state? Finally, what implications do these case studies have for public sphere theory?

Case 1: The Fierce Five

In 2016, current and former members of the USA women’s gymnastics team came forward to report widespread abuse at the hands of Larry Nassar publicly. Nassar, a team physician employed by Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics, used his trusted medical position to assault and molest over 500 gymnasts under the guise of medical treatment. Over 150 women gave impact statements in court describing how they sought treatment from Nassar for sports injuries as minors; instead, he sexually assaulted them and claimed it was a form of treatment. The abuse spanned two decades but was ignored by the organizations mentioned above, as well as the U.S. Olympic Committee. A subsequent lawsuit brought by 90 victims further revealed that the FBI possessed credible complaints and corroborating evidence of Nassar’s extensive abuse but was “grossly derelict” in their duties–declining to interview gymnasts, failing to transfer the complaint to Nassar’s employers or report child abuse to relevant authorities, and lying to Congress (Casarez et al., 2022). The 2019 documentary “At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal” chronicles the criminal case and extensive list of charges levied against Nassar, as well as the lives affected.

The stories shared by current and former competitors, alongside the official results of the cases, served as catalysts for a larger movement advocating for systemic change within USA Gymnastics and allied organizations. The 2012 and 2016 Gold Medal teams, known respectively as “The Fierce Five” and “The Final Five,” became recognizable symbols of the movement. Simone Biles, Aly Raisman, and Gabby Douglas were central figures.

Survivors like Aly Raisman and Simone Biles continue to engage in advocacy on behalf of victims of sexual abuse and put public pressure on USA Gymnastics to focus on athletes’ physical safety and mental well-being (often citing their mental health challenges, including depression, as a result of the abuse they suffered). An attorney who has represented Nassar survivors told ABC News, “The changes that matter to the athletes honestly are because Simone insisted on it” (Lenthang, 2021, para. 31). Indeed, she and other survivors said they were not satisfied with investigations. Until there are meaningful reforms, Raisman said, “we can’t believe in a future that’s safe for the sport” (Lenthang, 2021, para. 22).

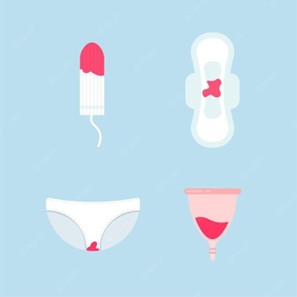

Case 2: Menstrual Equity

In 2015, we witnessed a sharp rise in public rallies, legislative activism, and community advocacy to end period stigma and curb “period poverty.” Period poverty refers to inadequate access to menstrual education, hygiene products, and sanitation infrastructure. In addition to general health concerns, advocates say period poverty contributes to chronic absenteeism, as well as mental and emotional stress. According to the Alliance for Period Supplies, two in five (40 percent) of people in the U.S. experience period poverty. These problems are also well-documented around the globe. The movement for menstrual equity was and continues to be led by teens nationwide (Silva, 2022). Many youth leaders started mission-driven organizations to generate awareness of period poverty and expand accessibility to menstrual hygiene products. For example, Nadya Okamoto founded the non-profit PERIOD. when she was just 15 years old. The organization, whose impact is now global, maintains a youth advisory council responsible for governance. It is tasked with providing strategic advice to its Board of Directors and staff on decision-making and program design.

The inaccessibility of menstrual hygiene products is known to be due, in part, to the “tampon tax”–a local tax (imposed by a state, county, or city government) collected on the retail purchase of such products. This sales tax denotes menstrual hygiene products like tampons or pads as luxury items (as opposed to groceries). As a result, these medically necessary products can cost an individual hundreds of extra dollars in taxes per year (on top of the $6,000 they spend on the products before tax during their lifetime).

Advocates have focused much of their efforts on repealing the “tampon tax” in numerous states, which they argue constitutes a discriminatory economic burden–one that contributes further to issues like isolation and infection. According to Period Law, 29 states are now tax-free thanks to volunteer attorneys, state-based advocates, and national period equity organizations working to advance state and federal period equity policies (sometimes via class action lawsuits). Meanwhile, 21 states are not tax-free, which advocates say allows local governments to profit from people’s periods. Period Law estimates that repealing the “tampon tax” in these states would net $82 million in annual savings. In tandem with repealing this tax, advocates have lobbied for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) to cover the total cost of period products.

Youth continue to be instrumental in advocating for changes to laws and policies involving essential accessibility of period products in schools and prisons. Indeed, a core goal of the menstrual equity movement is to make period products freely available in all public school restrooms, prisons and jails, and restrooms of public buildings. Concerning schools, they argue that period products should be available in all bathrooms so transgender students are not excluded. As of 2024, 28 states and Washington D.C. have expanded access to period products in schools with well over 100 bills being considered by other state legislatures (check out this interactive map of menstrual equity legislation from the Alliance for Period Supplies). Teen-led groups are also highly active in hosting local period product drives and establishing community-based period distribution programs to meet individuals’ immediate needs.

Notably, advocates say the movement for menstrual equity does not exist in isolation. In a 2022 interview with Stateline, Jennifer Weiss-Wolf argued, “There’s so much regressive action happening in state legislatures right now when it comes to abortion, when it comes to trans rights and health, when it comes to education, that menstruation can’t be sort of looked at in a vacuum… How can we make these laws even stronger, more inclusive, and more far-reaching so that there is nobody for whom menstrual access is a barrier to their participation in public life?” (Wright, 2022, para. 8). To learn more about the menstrual equity movement and the youth propelling it, check out organizations like 601 for Period Equity, Help a Girl Out, and the Myna Mahila Foundation.

Case 3: Climate Change

In the late 2010s and early 2020s, youth-led lawsuits against federal agencies and state governments were filed. The subject of said lawsuits was climate change and the downstream impacts of present-day decisions that demonstrably failed to regulate the destructive impacts of fossil fuels and greenhouse gases. While few of these cases have gone far in the legal system or resulted in favorable outcomes for climate change activism, their increasing frequency suggests momentum for climate justice. Below are a few notable cases, all of which received representation from the non-profit public interest law firm, Our Children’s Trust:

- Juliana v. United States (2015) – The 23 youth plaintiffs from Oregon argued that the U.S. government “continued to use and promote the use of fossil fuels, knowing that such consumption would destabilize the climate, putting future generations at risk. By doing so, the plaintiffs argued, the U.S. government had violated their constitutional rights to life, liberty and property” (Rott, 2020, para. 3-4). The case was dismissed in 2020 when the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the plaintiffs made a compelling case for action but “reluctantly” concluded that “such relief is beyond our constitutional power” (Juliana v. United States, 2020, p. 11). The plaintiffs were allowed to amend their complaint to seek a declaratory judgment, and in 2023, the case was officially revived by a federal judge and cleared for trial. In their decision, the judge wrote, “It is a foundational doctrine that when government conduct catastrophically harms American citizens, the judiciary is constitutionally required to perform its independent role and determine whether the challenged conduct, not exclusively committed to any branch by the Constitution, is unconstitutional” (E360 Digest, 2023, para. 6).

- Held v. Montana (2020) – In addition to representation from Our Children’s Trust, this case also involved legal representation from the Western Environmental Law Center and McGarvey Law. The 16 youth plaintiffs from Montana argued that a provision within the Montana Environmental Policy Act (MEPA), which “forbid[s] state agencies from considering the impacts of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or climate change in their environmental reviews,” violated youths’ “fundamental right” to a “clean and healthful environment” as declared in the state constitution (Bookman, 2023, para. 3-4). On August 14, 2023, a judge sided with the youth plaintiffs when they ruled that “the state’s failure to consider climate change when approving fossil fuel projects was unconstitutional” (Gelles & Baker, 2023, para. 1). The landmark ruling was the first big win for the youth-led U.S. climate litigation movement. In the victory order, the state wrote that the plaintiffs successfully proved “past and ongoing injuries resulting from the State’s failure to consider GHGs and climate change, including injuries to their physical and mental health, homes and property, recreational, spiritual, and aesthetic interests, tribal and cultural traditions, economic security, and happiness” (Held v. Montana, 2023, p. 86, lines 18-22). The order went on to confirm the “causal relationship” between the state’s permitted fossil fuel activities and the “resulting environmental harms,” which plaintiffs proved disproportionately harms children and youth (Held v. Montana, 2023, pp. 87-88). The Montana attorney general swiftly appealed the decision, but Montana’s Supreme Court denied the motion. The initial victory and more recent denial of the state’s appeal not only marks a win for climate activism writ large but also represents a welcome spotlight on youths’ desire and ability to fight for their future in legislative spaces.

- Genesis B. v. United States Environmental Protection Agency (2023) – The 18 youth plaintiffs from California have argued that the EPA “violated their constitutional rights by failing to protect them from the effects of climate change” in their uniquely lived spaces and circumstances (Brady, 2023, para. 1). Specifically, in allowing the burning of fossil fuels which produces carbon dioxide and warms the climate–noting the EPA’s own 2009 finding that “carbon monoxide, a greenhouse gas, is a public health threat, and children are the most vulnerable” (Brady, 2023, para. 7)–the plaintiffs allege the EPA has been derelict in their explicit duty to keep the air clean and control pollution to protect the health and welfare of the nation’s children. Like the amended complaint in Juliana v. United States, the plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explained theories of both the public sphere and counterpublics in connection to the broader study of rhetorical theory. The study of publics and counterpublics helps sharpen our understanding of how rhetoric can be employed; this understanding then allows us to more effectively theorize how audiences are subject to rhetorical acts and persuasive discourse. This conceptualization of the public sphere began with the works of scholars such as Goodnight, Perelman, and Olbrechts-Tyteca, all of whom built off the theorizing of Habermas’s public sphere.

In addition to the earlier conceptualizations of the public sphere, we have also shown how rhetorical acts and discourse are, above all else, subject to elements of power, access, resources, and identity–elements that serve to uphold those members of the public sphere who benefit from the status quo. Therefore, the concept of a “counterpublic” is necessary to our study of the public sphere–its inclusion allows us to better situate the study of rhetorical theory in ways conscious of audience, power, and oppositionality. This more contemporary conceptualization of counterpublics can be attributed to the wide range of scholars (e.g., Brouwer, Warner, Hauser, Chavez), all of whom prioritized envisioning the multiplicity of socially imagined spaces and collectives comprised of persons who sought to convey their interests, positions, and arguments that are otherwise not in alignment with that of the dominant sphere. Both the argumentation-focused and the critical iterations of the public sphere will prove to be indispensable as you proceed through your studies in rhetoric broadly.

Lastly, we augmented this explication of publics and counterpublics with a case study of young activists who survived the 2018 MSDHS shooting in Parkland, Florida. The Parkland youth sought to convey their needs and opposition to those in power through various rhetorical acts and situations, which sparked a nationwide movement. We then presented three additional brief case studies involving USA Gymnastics and “The Fierce Five,” the movement for menstrual equity, and youth-led climate change litigation, which we prompted you to explore using theories of the public sphere and counterpublicity.

References

Andersh, K., Francis, Z., Moran, M., & Quarato, E. (2021). Period poverty: A risk factor for people who menstruate in STEM. Journal of Science Policy & Governance, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.38126/jspg180401

Asen, R., & Brouwer, D. C. (2001). Introduction: Reconfigurations of the public sphere. In R. Asen & D. C. Brouwer (Eds.), Counterpublics and the state (pp. 1-32). State University of New York Press.

Asen, R. (2000). Seeking the “counter” in counterpublics. Communication Theory, 10(4), 424-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2000.tb00201.x

Associated Press. (2018, May 25). Parkland students stage supermarket ‘die-ins’ to protest chain’s NRA link. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/may/25/parkland-students-die-in-publix-nra-adam-putnam-protest

Beard, D. E. (2012). Introduction: On the anniversary of Habermas’s structural transformation of the public sphere. Argumentation and Advocacy, 49(2), 132-134.

Bell, V. (2007). The potential of an ‘unfolding constellation’: Imagining Fraser’s transnational public sphere. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(4), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407083018

Berlant, L. (1997). The queen of America goes to Washington city: Essays on sex and citizenship. Duke University Press.

Bookman, S. (2023, Aug 30). Held v. Montana: A win for young climate advocates and what it means for future litigation. Harvard Environmental and Energy Law Program. https://eelp.law.harvard.edu/held-v-montana/

Brady, J. (2023, Dec 11). 18 California children are suing the EPA over climate change. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/12/11/1218499186/18-california-children-are-suing-the-epa-over-climate-change#:~:text=Eighteen%20California%20children%20are%20suing,lawsuit%20is%20called%20Genesis%20B

Brouwer, D. C. (2006). Communication as counterpublic. In G. J. Shepherd, J. St. John, & T. Striphas (Eds.), Communication as…: Perspectives on theory (pp. 195-208). Sage Publications.

Campbell, K. K. (2005). Agency: Promiscuous and protean. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies. 2, 1-19.

Casarez, J., Perez, E., Frehse, R., & and Sgueglia, K. (2022, June 9). Olympic gymnasts Biles, Raisman, and Maroney are among dozens seeking $1 billion from the FBI over the botched Larry Nassar sex abuse investigation. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/08/us/larry-nassar-fbi-mishandling-claim/index.html

Chávez, K. R. (2011). Counter-public enclaves and understanding the function of rhetoric in social movement coalition-building. Communication Quarterly, 59(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190473-17

DeLuca, K. M. & Peeples, J. (2002). From public sphere to public screen: Democracy, activism, and the “violence” of Seattle. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19(2), 125-151.

Dewey, J. (1954). The public and its problems (rev. ed.). Swallow Press. (original work published 1927).

E360 Digest. (2023, June 2). Youth climate lawsuit against federal government headed for trial. Yale School of the Environment. https://e360.yale.edu/digest/juliana-youth-climate-lawsuit-trial

Felski, R. (1989). Politics, aesthetics, and the feminist public sphere. In Beyond feminist aesthetics: Feminist literature and social change (pp. 154-182). Harvard University Press.

Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 109-142). The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Gelles, D., & Baker, M. (2023, Aug 14). Judge rules in favor of Montana youths in a landmark climate case. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/14/us/montana-youth-climate-ruling.html

Goodnight, G. T. (1982). The personal, technical, and public spheres of argument: A speculative inquiry into the art of public deliberation. Argumentation and Advocacy, 48, 198-210.

Greene, R. W. (1998). Another materialist rhetoric. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 15, 21-41.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger & F. Lawrence, trans.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press (original work published 1962).

Hauser, G. A. (2008). Vernacular voices: The rhetorics of publics and public spheres. University of South Carolina Press.

Held v. Montana, No. CDV-2020-307 (1st Dist. Ct. Mont., Aug. 14, 2023). https://westernlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2023.08.14-Held-v.-Montana-victory-order.pdf

Jackson, S. J. & Foucault-Welles, B. (2015). Hijacking #myNYPD: Social media dissent and networked counterpublics. Journal of Communication, 65, 932-952.

Juliana v. United States, 947 F.3d 1159 (9th Cir. 2020). https://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2020/01/17/18-36082.pdf

Lenthang, M. (2021, July 26). How USA Gymnastics has changed since the Larry Nassar scandal. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/usa-gymnastics-changed-larry-nassar-scandal/story?id=78839442

Macur, J. (2021, Dec 13). Nassar abuse survivors reach a $380 million settlement. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/13/sports/olympics/nassar-abuse-gymnasts-settlement.html

March for Our Lives. (2024). Mission and story. https://marchforourlives.com/mission-story/

Nash, K., & Bell, V. (2007). The politics of framing: An interview with Nancy Fraser. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(4), 73-86. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190473-17

Negt, O., & Kluge, A. (1993). On the dialectic between the bourgeois and the proletarian public sphere. In Public sphere and experience: Toward an analysis of the bourgeois and proletarian public sphere (P. Labanyi, J. O. Daniel, & A. Oksiloff, Trans.) (pp. 54-95). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1972)

Ono, K. A. & Sloop, J. M. (1995). The critique of vernacular discourse. Communication Monographs, 62, 19-46.

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The new rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation. University of Notre Dame Press.

Rott, N. (2020, Jan 17). Kids’ climate case ‘reluctantly’ dismissed by appeals court. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/01/17/797416530/kids-climate-case-reluctantly-dismissed-by-appeals-court

Silva, A. (2022, July 28). Teens are pioneering the nationwide movement for menstrual equity. Ms. Magazine. https://msmagazine.com/2022/07/28/teens-period-products-menstrual-equity/

Sloop, J. M. & Ono, K. A. (1997). Out-law discourse: The critical politics of material judgment. Philosophy & Rhetoric, 30, 50-69.

Squires, C. R. (2002). Rethinking the black public sphere: An alternative vocabulary for multiple public spheres. Communication Theory, 12(4), 446-468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00278.x

Stephenson, M. (2002). Forging an indigenous counterpublic sphere: The Taller de Historia Oral Andina in Bolivia. Latin American Research Review, 37(2), 99-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0023879100019531

Warner, M. (2002a). Public and private. In Publics and counterpublics (pp. 21-63). Zone Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1qgnqj8.4

Warner, M. (2002b). Publics and counterpublics. Public Culture, 14(1), 49-90. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-14-1-49

Wright, A. (2022, May 16). Teens’ period poverty activism has stirred lawmakers to action. Stateline. https://stateline.org/2022/05/16/teens-period-poverty-activism-has-stirred-lawmakers-to-action/

- In their immediate activism following the Parkland shooting, González was represented by a different first name. González came out as nonbinary in May 2021 (using they/them pronouns) and re-emerged as “X.” We honor their identity throughout the chapter. ↵