Chapter 17: The Rhetoric of Secrecy and Surveillance

This chapter is about the Secrecy Situation. The first section defines this “situation,” covers key terms related to secrecy rhetoric (e.g. arcanum, secretum, surveillance, and sousveillance), and considers how these concepts are relevant to the documentary “The Great Hack.” The second section offers a short history of famous conspiracy theories and how they have been a recurring feature of western European and American history. The final section considers how rhetoric offers useful concepts for identifying and describing secrets. [recording forthcoming]

Watching the video clips embedded in the chapters may add to the projected “read time” listed in the headers. Please also note that the audio recording for this chapter covers the same tested content as is presented in the chapter below.

Chapter Recordings

- Part 1: Secrecy Rhetoric (Video, ~20m)

- Part 2: Defining the Conspiracy Theory (Video, ~40m)*

- Part 3: Rhetoric, Psychoanalysis, and Secrecy (Video, ~TBA)

*Please note that this recording is drawn from a different course and the preview that appears at the beginning does not reflect the progression of this textbook.

Read this Next

- Stahl, Roger. “Weaponizing speech.” Quarterly journal of speech 102.4 (2016): 376-395.

Part 1: Secrecy Rhetorics

Secrecy creates a “situation” in two ways.

On the one hand, secrecy is a spectacle. The term “spectacle” describes how a public’s attention is steered from one scandal or emergency after another. The spectacle demands all of our attention but makes it impossible to focus upon just one thing that is happening. As Guy Debord writes, “With consummate skill, the spectacle organizes ignorance of what is about to happen and, immediately afterward, the forgetting [of what has happened]. The more important something is, the more that it is hidden.” That’s the logic of the spectacle: secrets keep us tuned in because there is always another revelation or scandal to grab our attention. Often, this resonates with how “rhetoric” is described in public life. Rhetoric is often understood as the medium for keeping and communicating secretly, using words and images to create the impression of absence, heighten suspense, and grab public attention.

On the other hand, secrecy creates rhetorical situations of coded communication. When a secret exists between two or more people, keeping the secret means communicating in public with purposeful double meanings or by not communicating at all. When secrets are brought out into public, they separate members of an in-group from an out-group. Joshua Gunn describes the word “shibboleth,” a famous secret password, as an example of this relationality in Modern Occult Rhetoric:

the Ephraimites and the Gileadites are warring, and the latter defeats the former. The Gileadites fashion a blockade to catch fleeing Ephraimites and establish a password to let their friends through. Each escapee is asked to pronounce the word “shibboleth,” ancient Hebrew for “ear of corn.” In the dialect of the Gileadites the word was pronounced with a “sh,” while the Ephraimites pronounced it with a “s.”

The shibboleth is a secret password, a covert mode of communication used to constitute, separate, and police. Passwords and surveillance technologies serve a similar function today. By enlisting secrecy, communication forges social bonds and creates novel configurations of knowing and not knowing.

Linguistic Roots of Secrecy: Arcanum and Secretum

In sum, the secrecy situation is both

- a general curated, immersive, and addictive experience of culture by a public trained to expect secrecy at every turn and

- the particular relational experience – both intimate and oppressive – of holding privileged knowledge together with others.

The contemporary word “secret” is related to two terms developed in the Roman empire: arcanum and secretum. These describe distinct but related ways of thinking about secrecy, specifically the secrets that a ruling class or government keeps relative to a wider public. These forms of secrecy are modes of political time management.

- Arcanum comes from the noun arca, which means chest, coffin, or treasury. It is a secret that is not available because it has been buried, put under wraps, removed, or locked away from visibility or use. The defining characteristic of the arcanum is that its contents are inaccessible. As a mode of time management, the purpose of the arcanum is to control information indefinitely. The arcanum Imperii is the secret of state. These kinds of secrets restrict the flow of information by walling it off and making it inaccessible.

- Secretum comes from the verb secenere, which means “to sift apart.” It is a secret that arises due to the social separation between the suspicious and the ruling class who is ‘supposed to know’ some hidden truth. The defining characteristic of the secretum is that it is always part-in and part-out of public view. Some aspects of the secret drip into the public’s awareness, while other aspects remain outside of it. As a mode of time management, the purpose of the secretum is to innoculate or propagandize by gradually allowing the secret into the open. However, the secretum never comes out all at once. Instead, it maintains a balance between knowing the secret and knowing that we do not know it.

Subjective and Objective Secrets

Next, let’s think about a different conceptual pairing that describes two very different kinds of rhetoric used to communicate information about secrets. These are subjective and objective secrets, offering a functional difference between kinds of secrets that demand different kinds of institutional response. What this means is that subjective and objective secrets must be protected differently and fit into different categories in terms of the kinds of information that they contain.

| Subjective Secrets | EXAMPLES |

|

“Loose Lips Sink Ships” |

Let’s start with subjective secrets, which contain four key features. Subjective secrets are compact, or expressed with brevity, transparent, or readily understandable, changeable, or can be revised, perishable, or live in short-term public memory.

During World War II, the temporary position of a ship or service persons would be a subjective secret. The secret is easy to understand, it is brief, temporary, and if necessary it can be changed. Another example is the World War two era phrase “loose lips sink ships”. This phrase contains an argument that implies a civic obligation, shut up about your work if you want the nation to stay safe. It’s reasonably easy for us to understand that even at the distance of 70-80 years when it first circulated. It is also easy to think up variants on this phrase such as “snitches get stitches” or “see something say something”. Each communicates a message about secrecy for the moment in which it was shared in public.

| Objective Secrets | Nuclear Fission |

|

Next, let’s consider objective secrets. Objective secrets also have four key features, they are diffuse or expressed in many words, they are technical, or unavailable to lay audiences or audiences that do not have the required expertise, they are determinable, by individual deduction, and they are eternal or live in long-lasting public memory.

An example of an objective secret would be nuclear fission. Nuclear fission is the process of splitting the atom, this process is not an easy or simple thing to explain but requires many words. It is not easily understood by non-technical audiences, but someone who is sufficiently informed could in theory come up with these ideas on their own with enough research. Finally, fission never stops being dangerous. Like the existence of UFOs/UAPs, it is a long-term secret, kept because its potential effects do not dissipate over time.

Anamorphosis as Metaphor for the Secret

In Chapter 9: Visual Rhetoric, we covered the concept of anamorphosis as an example of presence. Anamorphosis describes a visual shift in perspective and a shift in what an observer knows. Historian Martin Jay tells us that, traditionally, anamorphosis describes a visual technique employed by painters that “allows the spectator to reform a distorted picture by use of a non-planar mirror.” (48) The English language inherits anamorphosis from the Greek terms ana (again) and morphe (form). It conventionally refers to a painting technique for manipulating perspective through purposeful distortion. A famous example of anamorphosis is the Renaissance painting shown below, The Ambassadors (1533) painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.

Looking the painting head-on, there is one disproportionate element: the large and distorted shape that covers the lower half of the canvas. But from the proper angle, the distortion is revealed as a skull. The spectator can see it fully and upright only as they move away from the canvas’s center. Head-on, the painting overflows with representations of knowledge. It is littered with mandolins, measuring devices, scrolls, and globes. ‘Viewed at an angle,’ however, the skull adds an extra element, one that carries an important significance for the viewer. The skull tells us that something was missing when we first glanced at the image. Anamorphosis describes the visual transformation of the skull, moving from an unintelligible blob to a recognizable form, once viewed from the corrected perspective. The skull offers an analogy for the logic of secrecy: hidden meaning is only available when the audience to this painting shifts their perspective.

Anamorphosis need not be a visual phenomenon. There are many scenarios where secrets lie in plain sight, right in front of us, and it isn’t until the audience’s perspective shifts that we recognize ourselves as in the presence of a secret. In the clip below from the film Searching, the protagonist (played by John Cho) has recently lost his daughter. He’s done everything in his power to find her using the resources of the police and has to the best of his ability scoured all of his daughter’s social media postings. At the moment that he submits commemorative materials for his daughter’s funeral, he notices something that he had not before: an anamorphic image that had been part of the social media profile that his daughter had been using, and which he had found after her disappearance.

Example of anamorphosis from the (2018) film Searching.

In the first instance, the main character saw the stock photo image as insignificant, much as a viewer approaching the skull of The Ambassadors for the first time. There was no reason to question whether or not the person that his daughter had been chatting with was using their own authentic image. However, after coming to find out that the image is a stock photo, there is an anamorphic shift such that the meaning of these previous conversations changes. It suddenly becomes possible that his daughter was catfished, and it renews the main character’s drive to find his missing child. Looking at the image from a different angle produces a different meaning. In the first instance, the character saw the image, not knowing what it meant. Then, anamorphosis occurs, changing the meaning of the image and changing the course of events in the film.

Whistleblowing, Leaking, and Stove-Piping

The term secretum describes how some secrets are “open,” existing between what is known and what is unknown, separating information between those who rule and those who are ruled. The umbrella term secretum also captures how secret information trickles from an official source into the public. Three common terms describe this movement of secrecy: whistleblowing, leaking, and stove-piping. Each is defined below and paired with an extended example of how these terms work together:

- Whistleblowing is when a member of an organization circumvents or goes around the institutional hierarchy to reveal compromising information about wrongdoing. If you are working in a group if you catch someone cheating on an exam and you report it to the instructor, that would be an example of whistleblowing. You circumvented the institutional hierarchy in some sense by going around your relationship with this other person in order to report it to the instructor. Because the secret is attributable to you because you revealed it to them, you would be the whistleblower.

- Leaking occurs when secret information is shared with a third party to preserve the anonymity of an original source. If you were to catch someone cheating on an exam then pass that information to another person in the class who then passes it on to the instructor, that would be leaking. That way you would have shared that information with a third party, this other friend, who would have then passed it along in order to keep your identity a secret.

- Stove-piping is when confidential information is released strategically to polarize public opinion. If you have a grudge against someone and then intentionally whistleblow or leak information that is false or incorrect to get them in trouble, that would be stove-piping. This term describes when information is labeled as a secret – likely with significant inaccuracies – to serve some personal or political goal.

Surveillance and Sousveillance

The last two key terms related to secrecy that we’ll consider here are surveillance and sousveillance.

According to Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, surveillance is the observation of interaction or behavior by a nonparticipant in the interaction. It can also be explained in terms of three functions.

- It is a form of social control or a way to encourage restrictions on behavior.

- It is a mode of capitalist participation or a way to harvest information for the purposes of individual, corporate, or partisan enrichment.

- Finally, it is a demand for disproportionate transparency from the subject under observation. In this case, information must be known for public safety or security, such as viral tracing data or essential national security information.

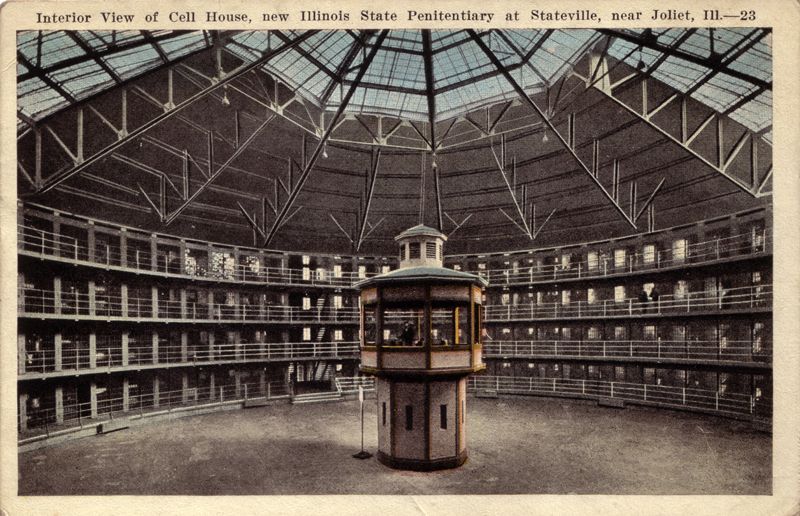

It’s important to note that surveillance technologies have been with us for a long time, like other secrecy functions of government, it is embedded in the history of official government institutions like prisons. One of the famous prison building structures used for state surveillance is the panopticon. Before electricity or film, the panopticon created a system of visual surveillance within the prison. The idea of the panopticon is to exercise discipline through a visual arrangement of space, a guard in a central watchtower polices every cell and every cell may be seen at a moment’s notice with minimal patrolling. It also encourages watching among the incarcerated, each of whom has a different limited window upon the other cells in the prison. It illustrates that surveillance is a function of government and, like “loose lips sink ships”, that it is an ideology related to policing that people freely adopt. The question is why do we feel obligated to surveil and who is disproportionately surveilled relative to others?

Sousveillance describes techniques of looking back. It is a mode of watching that turns surveillance technologies back on the watchers. When we think of transparency watchdogs, or people turning cameras back on scenes of police violence, this is sousveillance or the act of looking back. The image above is an installation called “inside/out” by the French artist JR. It depicts a large photographic mural that was sent on the ground along the Pakistani border and was meant to be captured by drones flown by Americans flying overhead. This look-back is intended to make the persons who are typically watched into watchers, reversing the conventional dynamics of state surveillance power.

Public Consciousness of Surveillance

Let’s consider an example of how surveillance is represented and how the public is trained to understand it. As we stated before, surveillance is the observation of interaction or behavior by a nonparticipant in the interaction. It is also a form of social control, a mode of capitalist participation, and a demand for transparency on the part of citizens. In the late 1990’s early 2000’s, surveillance was figured as a powerful policing tool, and digital surveillance technology was still in early development. This trailer conveys the message that corrupt institutions will misuse surveillance tools that are intended to protect people from violence. Let’s watch the clip and consider its relation to the concept of surveillance.

The film Enemy of the State tells the story of a district attorney, played by Will Smith, who accidentally comes upon a video of a political assassination in the United States. He is forced into hiding and is publicly scapegoated by the individuals played by Jack Black and Jon Voight, who plotted this assassination and who run a secretive government agency. Smith befriends a conspiracy theorist played by Gene Hackman, who enables him to avoid capture while attempting to clear his name.

Surveillance, the observation of one or more parties by another party not present in the communication exchange, is a major feature of the film. It also satisfies the three criteria of surveillance described above:

- Surveillance is depicted as a form of social control because Smith and Hackman are openly policed by a secretive agency that resembles the NSA.

- Smith participates in capitalist surveillance because he is most exposed when shopping with credit cards and on camera.

- The film ultimately demands disproportionate transparency by repeatedly exposing Smith to scrutiny and harm, despite his character’s record of government service.

Ultimately, it makes the case in 1999 that someone must watch the watchers and that more public transparency would ensure that people in charge of our surveillance tools are not also corrupt. Surveillance makes our actions are more and more available for policing and raises the likelihood that surveillance systems will malfunction or fall into dangerous hands. The need to look back is therefore deeply urgent.

Weaponized Speech and the Information Bomb Metaphor

When organizations leak large amounts of information into the public about corrupt institutions in governments, the act of looking back becomes connected to demands for transparency. This idea of sousveillance of the look back is what brings us to Stahl’s article which asks when and how does speech become weaponized? In his words, how can we speak about speech in an era of information warfare that has allowed notions of war and public communication to meld to a significant degree?

Metaphor is the foundation for understanding Stahl’s article, Weaponizing Speech. Metaphor criticism is the selection of a narrow vocabulary for events that are occurring in the world. It places A in terms of B where A is the tenor, the literal thing to which we refer, and B is the vehicle, the rhetorical screen that shapes how we see that literal object. In this case, we tend to see the tenor of speech through the vehicle of the weapon. As Stahl writes, a terrorist threat relies upon a transfer of meaning in which the state uses the sign as a tactic of information warfare. It communicates rhetorically, using metaphors. Stahl several examples of how the media has used metaphors in order to talk about terrorism.

“Media coverage comprises the ‘oxygen’ of terrorism… likening terrorism to a living organism that disappears in a conflagration.”

Here the vehicle is oxygen and the tenor is media. Media organizations are the literal thing to which coverage refers, while metaphorically, these act as the accelerant for terroristic activities because of the way that they circulate harmful messages.

Stahl also argues that mass media depicts terrorism as “noise and untranslatability” because “a terrorist’s speech cannot be speech.”

In this case, noise is the vehicle used to convey the tenor of terrorism. Because the literal event of terrorism cannot be understood as meaningful within the military framing of events, it must be instead understood as a distortion.

The Information bomb stages a similar metaphor. In this case, the vehicle, the I-bomb, metaphorically conveys a literal object, speech that reveals a state secret.

The metaphor of the information bomb circulated following the 2010 Wikileaks information releases, which initiated a wave of discourse fusing the frames of cyber-terrorism and weaponized journalism. The organization released enormous caches of military ground reports and diplomatic cables that exposed the mass deaths of innocent civilians, the use of torture and assassination, and the general failure of the U.S. military strategy in Afghanistan. Perhaps more significant than the revelations themselves however was the fact that as one journalist put it, virtually all of Washington declared WikiLeaks’ disclosures (e.g. of diplomatic cables) as acts of treason.

The conversation routinely pushed the disclosures into the frame of war, weaponry, and terrorism. The loudest voice in the Republican party was that of New York congressman Peter King, incoming chair of the house committee on homeland security who demanded that Wikileaks be put on the official state department list of terrorist organizations. In addition to describing the leaks as catastrophic and sabotaging our system, King made sure to characterize the information in weaponized terms. “They are providing the weapons to terrorist organizations giving them information which they can use to kill off Americans to compromise America’s standing around the world. The time bombs are out there and they are going to go off and by then it is going to be too late.”

The information bomb (or I-Bomb) is a metaphor for an allegedly dangerous information release. It exposes a secret by disclosing information as if it were a weapon, a bomb that explodes with unpredictable effects. It is, as Stahl describes it, weaponized speech, a metaphor in which spoken, written, or otherwise recorded information takes on the characteristics of a hypothetically destructive force or warlike threat. Sometimes, weaponized speech is a form of propaganda designed to create the impression or perception of a threat, encouraging a heightened military or police response while minimizing uncertainty over whether the anticipated, destructive effects will actually materialize.

Next, let’s consider a clip that illustrates a different instance of the I-bomb than is considered within Stahl’s article. The video below is a trailer for the Netflix documentary The Great Hack. Like Stahl’s article, the film is concerned with the weaponization of information.

The Great Hack offers an example of the I-bomb because it is also seeking to describe a strategic use of speech and language that is weapon-like in nature. The Great Hack also offers an example of surveillance: Cambridge Analytica fostered social control of public opinion enabled by a profit motive. Finally, The Great Hack it created a demand for transparency in the form of the documentary ‘look back.’ From a later point in time, we as an audience are invited to see the secrets that were once exposed and the destructive effects they had.

Are secrets permanent and enduring and are specific measures needed in order to protect that kind of secret or, are they temporary and changeable? Ultimately, secrets are ways of accounting for how information moves into the public. Secrecy isn’t just an arcanum, locked away like the arc of the Covenant at the end of Indiana Jones. It is a mode of strategic time- and information management that establishes a concrete relationship between those presumed to be “in the know” and the public who is supposed to believe in these institutions. It stages the relationship between rulers and the ruled, or in the case of The Great Hack, between corporations and consumers.

Part 2: Conspiracy Rhetoric

One of the reasons to study the rhetoric of secrecy is that it helps us to understand the logic of conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories are common ways of creating a spectacle of secrecy in public and personal communication. They also describe how secrets acquire a specific kind of performative force when they circulate in public. Conspiracy theories use rhetoric to attract audiences and capture them within a web of faulty reasoning.

Although it may seem like conspiracy theories are especially prevalent today, they have a long history in the United States. This section offers a short history of conspiracies, offering some context for how and why conspiracy thinking has been part of America’s common sense for the past two centuries.

Legal and Rhetorical Definitions of Conspiracy

According to the United States federal legal code, a criminal conspiracy is an agreement by two or more people to commit criminal fraud through illegal actions. Importantly, the plan to commit conspiracy does not have to be conducted in secret to be punishable by law – conspiracies can and do happen out in the open. The Mueller Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election cites two conspiracy statutes in discussing whether to bring charges to Donald J. Trump for election interference involving the Russian government and WikiLeaks in 2016. One of these, 18 U.S.C. § 371, creates an offense …

… “[i]f two or more persons conspire either to commit any offense against the United States, or to defraud the United States, or any agency thereof in any manner or for any purpose.”

As a kind of rhetoric, conspiracy theories are a repetitious form of disinformation that produces a paranoid mindset in an audience. For example, Peter Knight describes post 9/11 “outrageous conspiracy theories” as an “infinite regress of suspicion” in which “the location of the ultimate foundation of power is endlessly deferred.” (193) Many conspiracy theories resemble a “slippery slope” fallacy of reasoning in which secret information is presented as an unfolding pattern of exposure. Richard Hofstadter calls a common rhetorical organization of conspiracy theories in the 20th century “the paranoid style”:

The typical procedure [of the paranoid style] is to start with defensible assumptions and with a careful accumulation of facts, or at least of what appear to be facts, and to marshal these facts toward an overwhelming “proof” of the criminal conspiracy. It is nothing if not coherent – in fact, the paranoid mentality is far more coherent than the real world, since it leaves no room for mistakes, failures, or ambiguities. It believes that it is up against an enemy who is as infallibly rational as he is totally evil, and it seeks to match his imputed total competence with its own, leaving nothing unexplained and comprehending all of reality in one overarching, consistent theory.

It’s this “mentality” that Hofstadter identifies in the late 1950s, and which he argues has emerged out of major events in the past two centuries. These ‘events’ include the anti-masonic movement, the rise of evangelical and political demagogues in the United States, and the mainstreaming of Joseph McCarthy, Robert Welch, and the anti-communist John Birch Society.

The Anti-Masonic Movement (early 19th century)

The Freemasons are a secret society with a long medieval and European history. They are commonly associated with secrets because of the use of esoteric symbols, rituals, and hierarchy. Although their social and political significance has declined substantially over time, they still remain commonly associated with secrecy and conspiracy theories.

In the United States, the Freemasons were influential in the 18th and 19th centuries. Their activities were only partly secret because the fact of their hidden activities was public knowledge, particularly with the anti-Masonic movement. According to rhetorical and social movement theorist Leland Griffin, this movement emerged in the early 1800s. Here is how Griffin sets up the context for the fraternity of freemasons in the early 19th century:

“The conflict between secrecy and democracy would appear to be a recurrent phenomenon in our national history. Indeed, since the flowering of the modern secret society in the eighteenth century, anti-secretism as a state of mind has been an enduring fiber in the pattern of Western culture. In countries where the totalitarian climate prevails, the spirit of anti-secretism readily suppresses the secret order by the application of brute force. Where the question of suppression is left to the arbitrament of public opinion, however, the spirit of anti-secretism relies on persuasion. Throughout the century following the Revolutionary War, sentiment against the secret society was strong in America. During this period three attempts to arouse Public Opinion to the destruction of secret societies – and the Masonic Society in particular – may be noted. The second of these movements, which flourished from 1826 to 1838, roughly spanning the Jacksonian period, was by far the most noteworthy of the three.” (145-146)

We might note the following three points about this long passage:

- Griffin, who is writing in 1958, has no better word than “anti-secretism” to describe the counter-movement to the freemasons, which refers fundamentally to a movement-like injunction for the masons to disclose their secrets to the public. In fact, the word “transparency” is a recent addition to our political, legal, and public vocabulary. As recently as the 1960s, politicians, and academics referred to “disclosure” instead of “transparency” as an important feature of a healthy political sphere.

- The Masons are a significant group at the start of the 19th century, and that they dwindled in stature over time thanks to the efforts of a counter-movement of “anti-masons.”

- Anti-secretism “relies upon persuasion” and is therefore rhetorical. As Griffin notes, “the most significant figure in the band of aggressor rhetoricians was the political orator.” (152)

In the fall of 1826, a rumor was circulated among Freemasons of western New York. Allegedly, a former member of the lodge at Batavia, a bricklayer named William Morgan, was planning to publish the secret signs, grips, passwords, and ritual of Ancient Craft [Blue Lodge] Masonry. Morgan was imprisoned on a false charge and abducted from his cell by a small band of Masons. He was then taken to an abandoned fort above Niagara Falls. Shortly thereafter, all historical trace of him vanishes. Morgan’s disappearance triggered a public backlash in many states which Griffin describes as the “anti-Masonic movement,” which sought to expose the Freemasons as a not-so-secret criminal conspiracy.

When attacking the Freemasons, the anti-Masons relied upon “a ‘fund’ of public argument via various channels of media circulation, such as newspapers, tracts, public lectures, and sermons. In response, the Freemasons used rhetorical strategies that fell into two categories:

- The first strategy the Freemasons used was to counter-attack “the character and motives of Anti-masons. This strategy was a disaster. Griffin argues that it led the anti-Masons to extend their agenda to the complete destruction of Freemasonry itself, and later, “the destruction of all secret orders then existing in the country.”

- The Freemasons’ second rhetorical response … [was] “‘dignified silence’ in the face of the opposition’s attack.” According to Griffin, “states began to pass laws against extra-juridical oaths. Lodge charters were surrendered, sometimes under legal compulsion but often voluntarily, Phi Beta Kappa abandoned its oaths of secrecy, Masonic and Odd Fellows’ lodges began to file bankruptcy petitions, and membership rolls in the various orders began to dwindle to the vanishing point.”

Ultimately, the anti-Masonic movement disappeared, but the Freemasons remained. They have persisted through the late 20th and early 21st century, although their membership and public influence have diminished significantly. According to Joshua Gunn, the Freemasons were once a powerful organization because they laid claim to an “inexhaustible secret.” The community was sustained through the secrecy enmeshed with the organization’s hierarchy, its sacred rituals, and its guarded texts. But in the 20th century, in a flawed effort to get more members into the organization, the Freemasons began publicizing these texts. In this case, secrecy held that organization together and transparency pulled it apart. To sustain a public, the inexhaustible secret requires “a continuous dynamic obligation and commitment, achieved by a fetishized object whose information, meaning, or symbolism can never be fully revealed.” By giving up on secrets, the Masons also ‘gave up’ on what bound them together.

The Dreyfus Affair (late 19th – early 20th century)

The second example of early-20th century conspiracy theories is the Esterhazy Scandal, more commonly known as the Dreyfus Affair. On July 24th, 1894, Major Esterhazy, a French officer, offered to sell important French military secrets to the German military attache in Paris, Lieutenant Colonel Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen. Esterhazy gave him an artillery manual and a memorandum he had written on the subject of the new short 120 millimeter cannon being developed by the French, French troop positions and modifications in the battle order of artillery units, and plans for the imminent invasion and colonization of Madagascar. Shortly after it was received by the German attache, this information was leaked back to the French through planted French spies at the German embassy. After making incorrect deductions about where the information could have come from, a Lieutenant Colonel in the French army created a list of artillery officer trainees. The name “Alfred Dreyfus” was quickly singled out.

Dreyfus was a Jewish artillery officer. Those above him in the chain of command were openly anti-Semitic and Dreyfus was the only Jewish trainee. When news of his arrest was leaked, it was explained that Dreyfus had just finished training in the general staff, which is why he could obtain so much information. The evidence that resulted in his conviction was also markedly racist: it made Dreyfus the subject of suspicion because he was Jewish. Even Dreyfus’s handwriting did not match the handwriting on the leaked document from Germany. He was imprisoned on devil’s island in French Guiana where he spent about five years. Widely publicized around the world, the Dreyfus arrest strongly intensified antisemitic attitudes in France and Europe. The word “Dreyfusard,” a supporter of Dreyfus’s innocence, would have a familiar reference to the scandal in the early 20th century. Some famous supporters of Dreyfus included Queen Victoria, Henri Poincare, Mark Twain, and the Pope.

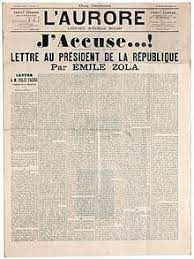

While he was in prison Dreyfus naively believed in the army’s ability to establish his innocence. He was unaware of the efforts to free him, his enemies in the general staff, and was convinced that high-ranking military officials were making efforts to find the real traitor. In 1896 new evidence emerged that identified the real culprit as Ferdinand Esterhazy. When officials suppressed the new evidence, a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy after a trial that lasted only two days. The army put additional charges against Dreyfus, which were based on forged documents. During this time, French novelist, playwright, and journalist Emile Zola published six open letters on Dreyfus’s behalf. In 1898 he published the famous letter titled “Je Accuse!,” – which was itself followed by seven more letters. This public pressure on the government to return to the case.

In 1899 Dreyfus returned to France for another trial. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence, but Dreyfus was pardoned and released. In 1906 Dreyfus was exonerated and reinstated as a major. He served during the whole of World War I. He ended his service at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and died in 1935.

The case is instructive for the way it communicates the role of racist ideologies in conspiracy theories. Max Horkheimer, who wrote “The Authoritarian Personality” in the wake of World War II, sought to establish a social-scientific basis for measuring and identifying the core traits of the anti-Semitic ideologies.

The Authoritarian Personality (1950) “seeks to discover correlations between ideology and sociological factors operating in the individual’s past.” It is about “hitherto largely ignored psychological aspects of fascism” by focusing “upon the consumer, the individual for whom the propaganda is designed.” It aims “to discover what patterns of socioeconomic factors are associated with receptivity, and with resistance, to antidemocratic propaganda.”

Horkheimer finds that antisemitism is characterized by contradictory attitudes that cannot be easily reconciled. For example, anti-Semitic ideology made Dreyfus out to be both too strong and too weak, too secretive and also too intrusive, as assimilating both too much and not enough. Dreyfus was accused on the basis of having fabricated his own handwriting. It was the contradictions of his character that were the telltale evidence that led him to be imprisoned. Dreyfus’s story is a warning because it was such a widespread source of misinformation. It also demonstrated how both racism and conspiracy theories were intertwined at the outset of the 20th century.

Part 3: Psychoanalysis and Secrecy

When we learn a secret, we receive a very specific kind of knowledge, one that is somewhere between staying unknown and becoming known. Secrets stay unknown because they concentrate knowledge among a limited number of people, restricting who is “in the know” to limit the flow of information. However, secrets also characteristically leak out of closed groups. It is difficult to keep a secret because it is not always apparent what or how we will unconsciously communicate what we wish to hide. Freudian slips and accidental references often give the secret away.

What is Psychoanalysis?

Psychoanalysis is the study of the unconscious and is most often associated with the theory and practice of talk therapy: a patient speaks their symptoms aloud, which an analyst interprets. In the Freudian tradition, the unconscious is often thought of as repressed memories or thoughts that have been pushed out of the conscious mind but which return with a vengeance, haunting our everyday lives. This is one of the ways that psychoanalysis theorizes the secret: as a quantity that we know in our unconscious, but which is not present to the conscious mind.

Later traditions of psychoanalytic thinking resist the idea that the unconscious is deeply repressed “inside” of the patient. Instead, secrets live “on the outside,” in everyday speech and our own under-noticed behaviors. This “outside” unconscious emerges as language choices and the metaphors we use, as well as the automatic assumptions we make of others and ourselves. We carry our history in the way we carry ourselves in the world and project a learned, more-or-less functional worldview.

On the philosophy and practice of psychoanalysis as the talking cure.

A key weakness of psychoanalytic thinking is that it sometimes emphasizes individual, ideational explanations above collective, structural explanations. For example, a psychoanalyst may point to a patient’s psychology or their need to reframe a situation before granting that deeper causes like structural racism and income inequality are important contributing factors to their emotional distress. For this reason, a more responsible version of psychoanalysis must seek a wider frame that is both individual and collective; both ideational and material.

Finally, speech (or talk) is the key point of overlap between psychoanalysis and rhetoric. Like rhetoric, psychoanalysis credits speech with the power to transform a person’s ideations – for better and for worse. Talk therapy allows some patients to recognize their symptoms as real secrets that they have kept from themselves, rather than dismissing or ignoring them. Talk cultivates awareness. For that reason, psychoanalysis is about knowing, anticipating, and building habits. It allows us to grow bigger around our secrets by giving them oxygen and making space for them in our lives.

Secrets are Rhetorical Repetitions

Rhetoric is also about speech and talk, adding the element of repetition. Before the word rhetoric was invented, a close equivalent was poetry, which was spoken aloud and remembered through repetition and meter. When the Greek sophists practiced persuasion, they departed from the oral performance of poetry that often reported important events. Instead, their rhetoric made speech an event. Frequently, they repeated especially compelling speeches and arguments, binding the invention of rhetoric to a kind of repetition. Even when understood as “figures of speech,” rhetoric is often an organized form of repetition:

- Anaphora repeats the sounds at the beginning of words. A similar sequence of sounds and persuasive propaganda are instances of anaphora.

- Asyndeton is the repeated omission of conjunctions between clauses, resulting in a hurried rhythm or vehement effect. Vini. Vidi. Vici. (I came. I saw. I conquered)

- Epiphora repeats words positioned at the end of a sentence. I want pizza, he wants pizza, we all want pizza!

Secrets are also recognizable because they are forms of repetition. We may know a secret is kept when a conspicuous action rises to the level of a pattern. For example, we may know that someone is planning a surprise party if they repeatedly divert from the topic each time a birthday is brought up. Often “twist” endings rely on us repeating the past, seeing new significance in details that seemed mundane at first. When we read for repetition, we also read rhetorically because we seek to understand under-noticed patterns that are part of our everyday life.

In the above clip, the character Michael Scott is terrible at keeping secrets, and threatens to disclose sensitive information through his repetitious behaviors. Jim struggles to prevent his secret from coming out while Michael repeatedly drops hints that reference Jim’s secret (e.g. “the P situation,” “he is in love with one of his co-workers who is engaged”). Indeed, he is so bad at keeping secrets that he eventually transforms into Jim, seeking to “repeat” him perfectly. These instances of repetition are what add up to a secret, making it increasingly apparent to all of those who are ‘out of the know’ that something has been hidden from them.

Those who are Supposed to Know and others who are Supposed to Believe

Like rhetoric, secrets have several different types of audiences. They are the “subjects supposed to know” and the “subjects supposed to believe.” Whereas the “subjects supposed to believe” are those who know that the secret exists by virtue of some other, higher authority, the “subjects supposed to know” are those who are presumed to have access to the secret.

Publicly known secrets are often described as “open.” Open secrets are those that are not fully or officially acknowledged but are nonetheless known and believed by a public who knows them to be true. Scandals are often open secrets before they become common knowledge. Other times, conspiracy theories try to create the appearance of an open secret by alleging that something is hidden when, in fact, there is no secret there at all. All secrets, open or otherwise, create a division between those who are “supposed to know” and those who are “supposed to believe.”

- Those who are “supposed to know” are the keepers of the secret. For many people, it is an aspirational position or one that they revere. Other people imagine themselves as the “supposed to know” as a fantasy of mastery. The subject supposed to know is the star of outlandish conspiracy theories, assumed to be authorities with access, power, and privilege. The subject “supposed to know” is supposed to know “the truth” about something utterly secret to us, whether it be about extraterrestrial life, a highly specialized form of knowledge, or a family recipe. In the traditional psychoanalytic setting, the therapist is often depicted as the subject “supposed to know,” or who is supposed to have the faculty of seeing what the patient cannot.

- Those who are “supposed to believe” are those who perceive themselves to be out-of-the-know, or who do not have the secret. They may be aware that a secret exists, and if so, they are meant to believe that some people in the first group (those “supposed to know”) have access to it (even if they do not). Those “supposed to believe” are certain about one thing: they know that they do not know, and therefore invest in the “subject supposed to believe” as the likely source of all the answers. In the traditional psychoanalytic setting, the patient is often depicted as the “subject supposed to believe,” or who is supposed to desire access to the secrets guarded by the subject “supposed to know.”

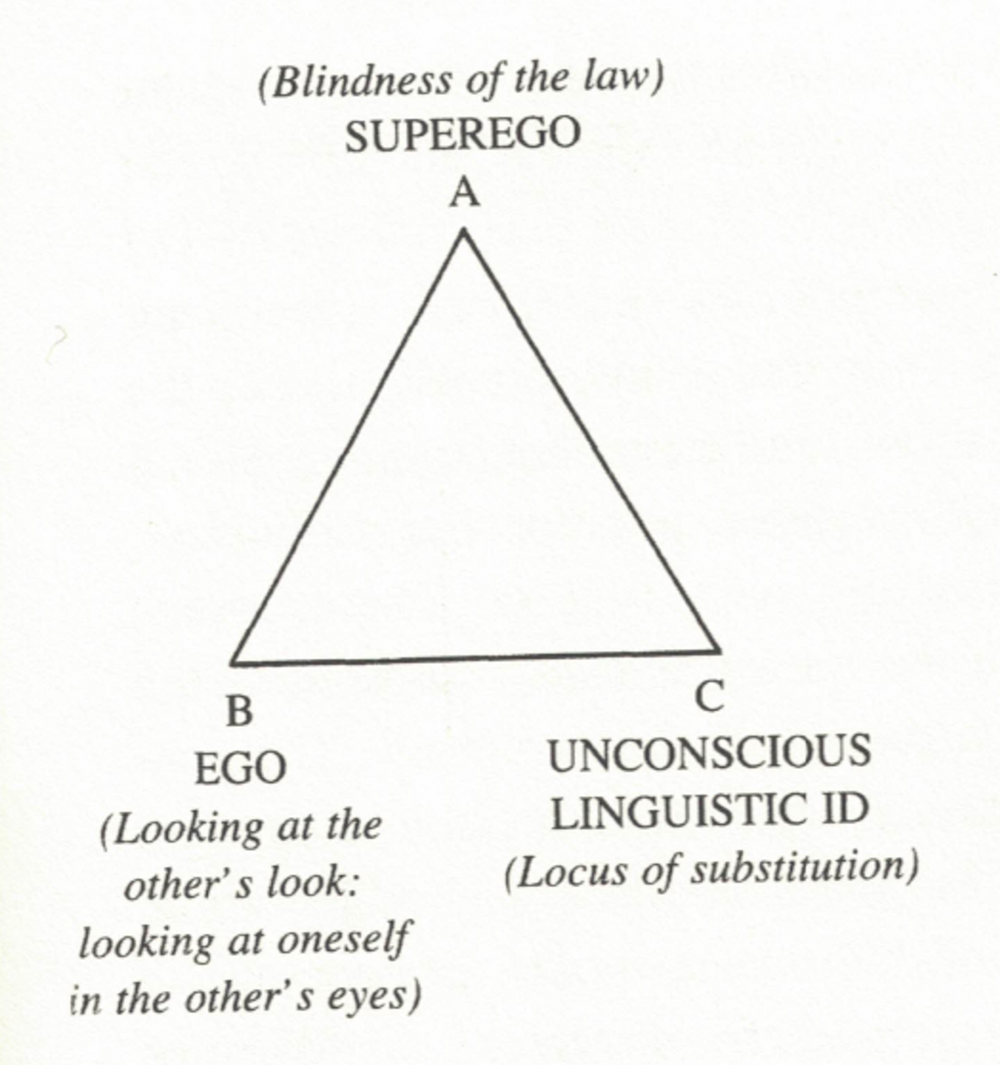

Ultimately, secrets are sustained by the belief of those people who are “supposed to believe” in the other group, who is “supposed to know.” Even if we do not have all of the answers, secrets are sustained by the belief that some other authority [e.g. a parent, professor, therapist, political representative, etc.] surely does have all the answers. In psychoanalytic theory, these “subjects supposed to know” are instances of the superego or the big Other, a psychological position from which we judge our own actions and which authorize our own judgment as accurate, moral, or legitimate.

Ego, Id, Superego

The Freud Museum on the Ego, Id, and Superego

The concept of the superego is part of a famous triad that includes the ego and the id. This framework is meant as a way to understand how the unconscious operates as a negotiation between different elements of an individual’s psyche. The following taxonomy is from the Freud Museum in London, with textbook commentary in the brackets:

- The id is the realm of appetites, wants, and passions that do not take ‘no’ for an answer. [This can also be thought of as the ‘need to know’ of the secret in the sense of a demand that it be let out or be released.]

- The superego is connected to morality and social norms, built out of identifications with one’s parents [and other big Others] , and can be extremely cruel. [This can also be thought of as the imagined position of those who are ‘supposed to know,‘ the secret and are presumed to restrict our access to it.]

- The ego faces the task of finding a balance between the demands of the id and the superego. That’s why the ego is the seat of the ‘defense mechanisms’ – there are so many dangers to avoid! [The ego describes the negotiation between the subject’s ‘need to know‘ and their imagination of those ‘supposed to know,‘ and all of the problems that arise because of it.]

Secrets = Knowledge Organized by Rhetoric

There are many official methods for “reading” secrets that seem to fall outside of the disciplinary boundaries of rhetoric, if only because of the way that they make secrets into a mathematical problem. One famous example is the prisoner’s dilemma, a hypothetical problem about the probability of two (or more) conspirators reporting their companion(s) – revealing the secret of the conspiracy – under interrogation. The prisoner’s dilemma has been used to map the probable behavior of wartime combatants, economic competitors, and diplomacy among nations. However, as the video below explains, although these models may calculate statistically reasonable outcomes actual or real-world results do not always correlate with these mathematical probabilities.

Psychoanalysis and rhetoric can also help us to understand the organized features of secrets, showing us formal characteristics that may not be apparent to us at first glance. One example is Edgar Alan Poe’s short story, “The Purloined Letter,” which is one of the first examples of detective fiction.

A YouTube video explaining the plot of “The Purloined Letter” in greater detail.

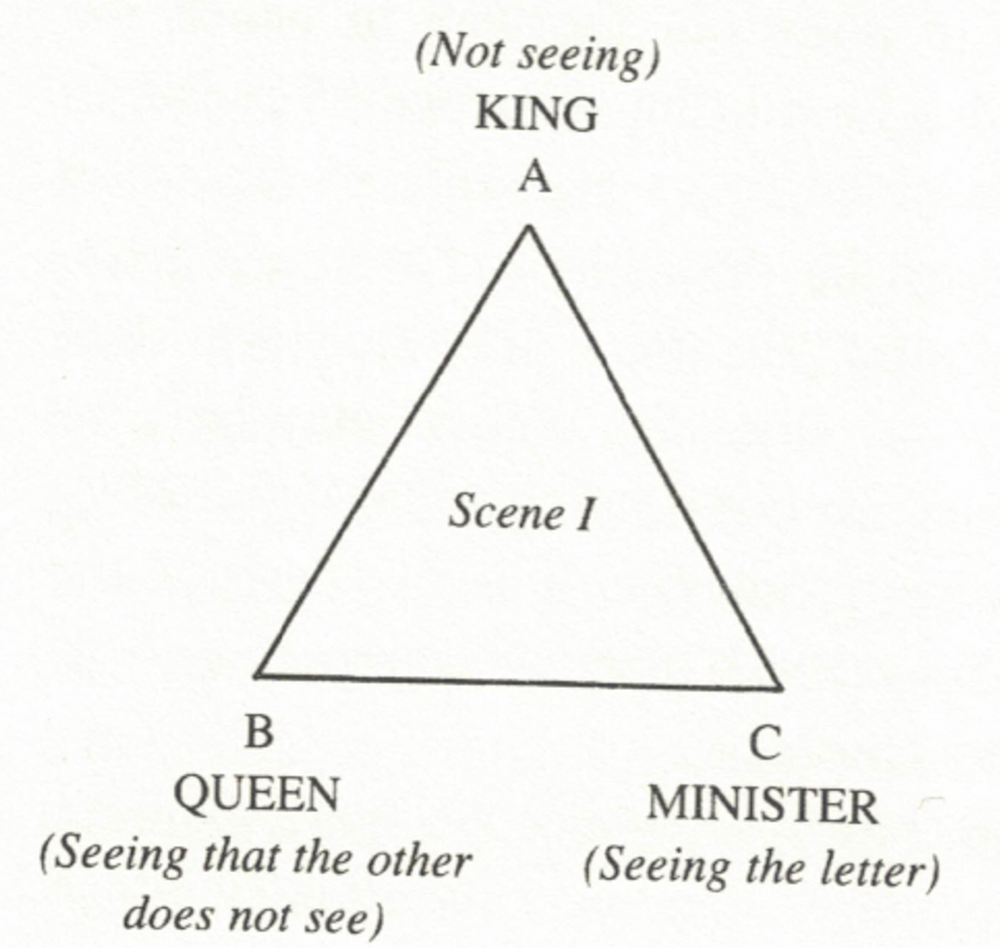

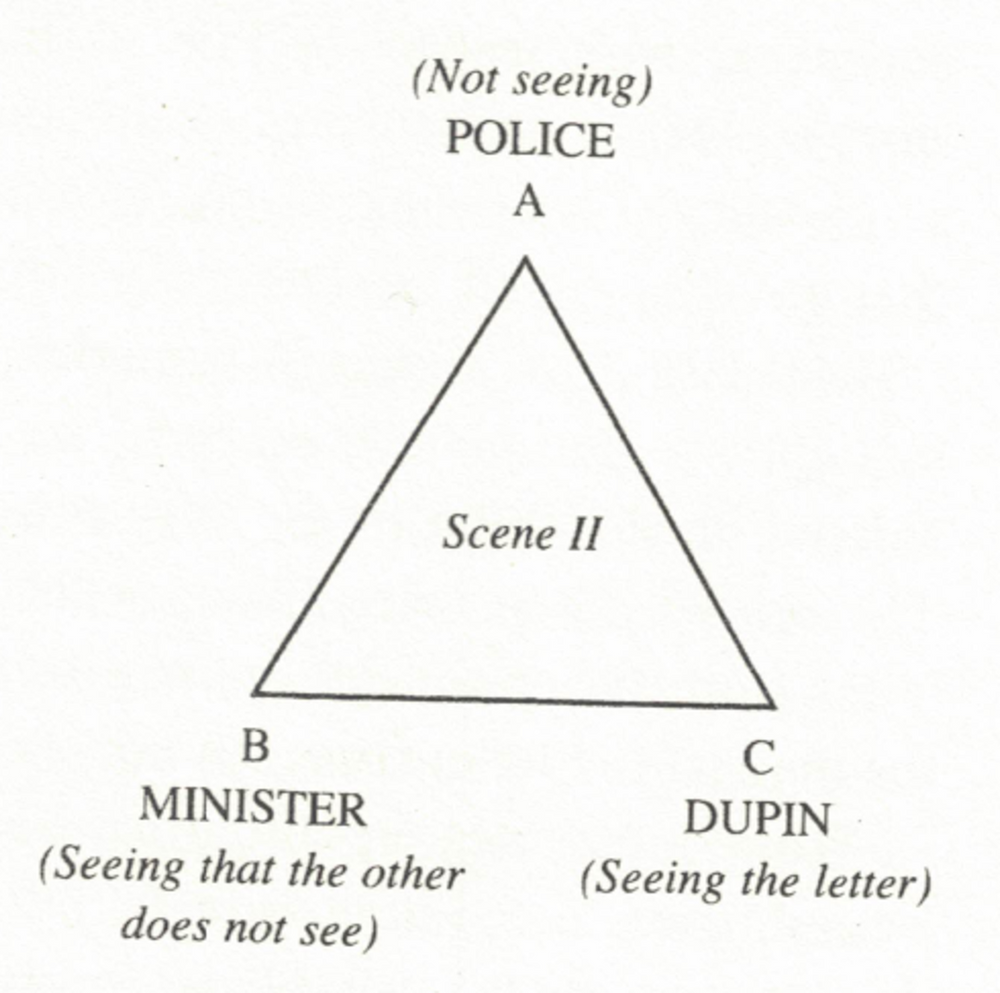

The story starts when a police officer, representing the Queen, bursts into the office of Auguste Dupin, a private investigator. This representative explains that the Queen has had a secret letter stolen. The theft occurred in a “royal boudoir,” where the King was also present. The contents of the letter are so sensitive that the Queen had wished to keep it secret even from the King. However, the crafty minister D- entered the royal chambers, saw the Queen was trying to hide the document, and took it, replacing it with a fake.

This is where the police get involved: they have staked out the Minister and have been unable to locate the letter, despite using state-of-the-art technology. Believing that Dupin will have better luck, the police task him with finding the letter. Dupin visits the Minister D- for a social call, and very quickly spots the letter: it is crumpled up on the Minister’s mantlepiece, laying in plain sight. He purposefully forgets an item at the Minister’s apartment and returns the next day. While Dupin is in the apartment, he stages a diversion in the square below and – while the Minister’s back is turned, replaces the stolen letter with a decoy of his own. The secret letter thus returns safely to its destination, and the reader never learns what it says.

Reading “The Purloined Letter” rhetorically illustrates how there is an organization and form to the secret at the story’s center. The story is partitioned into two scenes where the letter is “purloined” among three different characters. The first ‘scene’ occurs in the boudoir between the King, the Queen, and the Minister D-. The second occurs in the Minister’s apartment, between the police, Minister D-, and Dupin. By breaking the story down in this way, we can see that the secret is composed of three different “perspectives” or “points of view” with respect to undisclosed information:

- The first position is that of the King and the police: they are “dupes” who are entirely ignorant of the letter’s concealment. They represent the force of the superego, the laws that we impose upon ourselves, which is both all-powerful and disconnected from that which it sets out to govern. The letter is so secret that it does not even occur to them that it exists, or if they are aware that it exists, they are unable to see it when it is laying in plain sight.

- The second position is that of the Queen in the first scene and the Minister D- in the second. They are the “keepers” of the secret, the ones who possess the privileged information and make every effort to conceal it and keep it out of wider view. They represent the ego, the conscious self who is divided between obedience to the law and unrepressed instincts of the id.

- The third position is that of Minister D- in the first scene and Dupin in the second. They are the “perceivers” of the secret, the ones who are able to recognize what the second position is trying to conceal and, seizing the advantage, shift a balance of power. They represent the instincts and agency of the id, which captures how urges related to the body’s physical functions (e.g. seeing, eating) become automatic behaviors.

Most often, secrets are thought of as “hidden content,” in the sense that we want or need to know what those in positions of power or privilege have concealed from us. The story shows us how secrets are not hidden content, but a form or structure. For one thing, at no point do we ever learn what is in the purloined letter. Instead, we learn how and among whom the letter moves, and how the structure of not knowing, knowing, and seizing upon the secret may continually reproduce itself.

Ultimately, rhetoric and secrets are connected in several ways. Deciphering “talk” may allow us to perceive those things others have hidden – and which we keep hidden from ourselves. Identifying the “superego” may enable us to name the authorities in our lives or those who “have the secret.” Finally, the formal features of narrative unmask secrets as nothing more than positions we take with respect to privileged information: not having it, having it, or of unbalancing these power dynamics.

Additional Resources

- Bratich, Jack. “Public secrecy and immanent security: A strategic analysis.” Cultural studies 20.4-5 (2006): 493-511.

- Birchall, Clare. Shareveillance: The dangers of openly sharing and covertly collecting data. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

- Browne, Simone. “Introduction, and Other Dark Matters.” Dark Matters. Duke University Press, 2015: 1-30.

- Dean, Jodi. “Declarations of Independence.” Cultural studies and political theory. Cornell University Press, 2000: 285-305.

- Ewalt, Joshua P. “Visibility and order at the Salt Lake City Main Public Library: commonplaces, deviant publics, and the rhetorical criticism of neoliberalism’s geographies.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 16.2 (2019): 103-121.

- Fischer, Mia. “Pathologizing and Prosecuting a (Gender) Traitor.” Terrorizing gender: Transgender visibility and the surveillance practices of the US security state. University of Nebraska Press, 2019: 29-56.

- Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism.” Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage, 1995: 195-228.

- Galison, Peter. “Removing knowledge.” Critical Inquiry 31.1 (2004): 229-243.

- Galison, Peter. “Secrecy in three acts.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 77.3 (2010): 970-974.

- Melley, Timothy. “The Melodramatic Mode in American Politics and Other Varieties of Narrative Suspicion.” symploke 29.1 (2021): 57-74.

- Monahan, Torin. “Built to lie: Investigating technologies of deception, surveillance, and control.” The Information Society 32.4 (2016): 229-240.

- Ohl, Jessy J. “Nothing to see or fear: Light war and the boring visual rhetoric of US drone imagery.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 101.4 (2015): 612-632.

- Stahl, Roger. “Weaponizing speech.” Quarterly journal of speech 102.4 (2016): 376-395.

- Stahl, Roger. “A clockwork war: Rhetorics of time in a time of terror.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 94.1 (2008): 73-99.

- Thompson, John B. “The new visibility.” Theory, culture & society 22.6 (2005): 31-51.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.