Restoring the Embodied Art of Connection

A Value-Based Approach for Internationalization

Angelica Walton

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

While working on the front lines of the pandemic as a COVID Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurse in systems across the United States (U.S.), I was changed by the people and circumstances I encountered everyday. Walking into the unit each night, knowing I would be placing so many people into body bags by the next morning, became mentally overwhelming.

Before the pandemic, I had left my ICU work and was serving in my community as a home hospice and palliative care nurse. I found it uniquely healing and intimately human to be with people as they transitioned, surrounded by their loved ones, their pets, and the artifacts telling the stories of their lives. It was peaceful work, and the moments of sharing in the honest exchange of love and gentleness will forever remain a part of me. Leaving this work, and facing the grueling and lonely side of death and dying experienced by people during the pandemic, left me gutted. This kind of death felt so disconnected and far removed from the process of a natural and peaceful death. It felt like theft, and like I was playing a role in the wicked robbery of each person’s peaceful death. I stopped eating and sleeping, and had extreme nightmares and repeated dreams of patients and about circumstances I would have carried out much differently in a perfect world. I knew it was time for me to step away. This decision came with its own weighted guilt and shame, but for better or for worse, growing up in very unsafe (and complex-to-navigate) environments taught me a lot about walking away.

I was born in southern Louisiana, near the banks of the Mississippi River. In my life’s central moments, I’ve spent a great deal of time with this river. In that region of the country, the Mississippi—one of the three greatest rivers in the world based on its breadth and span—pours out and becomes the expansive gulf that bleeds into the Atlantic Ocean. While I was feeling the pull to walk away from front line nursing, the river and the trees, which have always been there for me to lean on, called out to me.

My partner and I took some time to live outdoors with our dogs and travel the land. We housed in a tent and spent life on the road, passing through many of the forests, mountain valleys, and deserts that span the Northwest region of the U.S. We cooked our meals over fires, learned the rhythms of bird songs, and became attuned to the changing weather patterns in the Pacific Northwest in order to navigate our days. I began writing poetry and engaging in nature photography in order to process, grieve, and remain present. This period was paradigm shifting, altering my understanding of what it might have been like when humans lived in this state of reciprocity with the world. Before our societies were overrun by the capitalism, corporate politics, industrialization, and product-driven markets that are now feeding into artificial developments across the globe, we noticed life because we had to. We were aware of good soil versus sick soil. We knew and paid attention to the patterns of the lunar cycle and how they affected not only the rivers and oceans, but us. We knew the names of plants, trees, and what to eat or drink when we needed more vitality versus when we were down or ill.

The questions that this learning evoked in me were many:

- How will there be a survivable world if we are not aware, present, and in relationship with all of these living beings on which we deeply depend?

- How have we become so disconnected?

- How are we so collectively blind to the vulnerability and giving nature of the water, the dirt, the trees?

- How will we return not only to noticing, but to caring enough to take action? Or perhaps the opposite: how might we stop taking action, and instead pause at times to experience life and what it means to simply be?

In 2022, as I started on the path toward my teaching career at the University of Minnesota (UMN) School of Nursing, these questions took on new meaning. I accepted a position as a Teaching Assistant while completing my own graduate studies in Integrative Health and Healing, and taught an introductory course on nursing skills and interventions in the Master of Nursing program.

This accelerated, 16-month program admits a diversity of students with previous non-nursing-related degrees and, often, well-established careers. On our first day together, as we began setting the environment and going around the circle to introduce ourselves, I learned about the characteristics of the individuals in this dynamic group. I was inspired by their stories, lives, clarity, wisdom, questions, and sense of creativity. Every person shared a life experience that led them to passionately pursue this path of becoming a nurse. I was filled with emotion as I sat listening. Each story, one by one, filled me with a sense of hope and reawakened my eyes to the possibility of transforming our fragmented health system. I realized that everything I thought I knew or had decided up until this point was based merely on my own experience, and that through fresh eyes, anything can be created. As individuals, our shared visions, ideas, and creativity become blueprints for what’s possible. As they told the stories of what led them to this place, the students also shared their hopes and ideas for a better world. Our meeting felt like a cleanse, a breath of fresh air. It was here that I began to feel that teaching was the next iteration of my purpose in nursing.

I took every opportunity during this semester to build community in our classroom by facilitating authentic dialogue. I shared truths about the complex challenges of bedside nursing today, and read poetry some mornings as a way to relate and hold space. At this time, COVID was still a difficult factor in the function of units and departments across the U.S. Many of my students were being introduced to the clinical setting and meeting the profession at a time when burnout, stress, and anxiety were at an all-time high.

Knowing this, I would sometimes start the day by having us engage in a meditation or expressive movement practice. And during weeks when testing was taking place, I tried to integrate more playful activities to help curb feelings of anxiety. The students learned these types of practices with full receptivity. I recall that I sometimes tried to skip these practices and move straight to the content; perhaps it was a busy week, or I just didn’t have it in me. The students would interrupt right away to ask for the activity so they could become grounded and let go of their distractions. This helped me understand just how essential these moments were for them, allowing them to center into their bodies and bring forward their ability to be present, connect, and receive.

At the end of the semester, students’ comments about having a regulated nervous system in order to fully engage and connect, whether in the classroom or with a patient, were profound. They described how having the space for open and honest dialogue—about their week, their stressors, their clinical experiences—made them feel valued. So much that I learned from this group of learners is now embedded into my way of approaching the learning environment today.

As I later moved into my role in a large health system, focusing on instructional education and content development for Integrative Therapies, I felt called to higher education. I felt certain that the classroom was a foundational space for addressing some of the complex systems issues burdening our communities today, and a place in which the transformation of the structures which map out the web of our social experiences, behaviors, and societal practices leading to disease and suffering can begin to take place.

Global Challenges Nurses Face Today

As a nurse educator, I am especially passionate about contributing to work addressing rising rates of loneliness, social disconnect, and mental health complications across our global communities. So many of the most significant diseases of today are related to these issues. Loneliness and isolation have been identified as significant health concerns (U.S. Surgeon General, 2022). Within the nursing workforce itself, suicide rates continue to rise, with an increase of 18% between 2007 and 2018 (Davis et al., 2021). The dynamics of the work environment are fragmented, and it is challenging for nurses to sustain their roles. New nurses are leaving the profession at alarming rates, with 30% leaving after year one and up to 57% leaving in year two (An et al., 2022).

Nurses comprise half of the global health workforce (Ren et al., 2024). In a meta-analysis evaluating nursing turnover across 14 countries since the year 2000, rates ranged from 8% to 26.6%, with a combined global turnover rate of 16% (Ren et al., 2024). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2018) estimates that by 2030, the number of nurses will have decreased globally by 7.6 million. The nursing shortage itself is one of the main reinforcing dynamics leading to turnover; with unsafe patient staffing ratios and reduced quality of care, nurses are under more chronic pressure, stress, and fatigue. This often leads to exhaustion and later to disconnection, and to what has been defined as burnout (Ge et al., 2014). The WHO (2019) recognizes burnout as a chronic, stress-induced, work-related disease, experienced by 30% of nurses globally. It is a severe syndrome, leading to challenges with memory and sleep, to depression, and to impatience (Pradas-Hernández et al., 2018).

Those learning to become nurses or to lead in today’s complex health system must be prepared with the skills and competence to care for themselves as well as they care for other individuals, families, groups, and communities. At all levels, today’s nurse must be aware of the high state of stress that societies face, and of ways to mitigate the effects. Nurses employed in health systems work in environments of continuous pressure, including changing schedules, night shifts, and sleep disruption, and all of this combined can be harmful to both their mental and physical health (Hammig, 2018). Today’s nurse must know how to regulate their own mind-body-emotion system in order to sustain their health, well-being, and connection to the healing aspects of nursing. They must know how to be present, to listen, and to participate in an authentic exchange of genuine caring. The energetic experience of human connection is part of the art of healing, and we need it woven into our way of being in order to create more sustainable and equitable health systems. A regulated system allows us as a social species to connect with one another and with the environment in ways central to our health and longevity, as this connection is a basic human need (Southwick & Southwick, 2020).

In my work I focus on understanding how, from a systems point of view, the factors leading to burnout can be addressed through innovative solutions. There is an immediate need to address the acute risks of burnout and of mental and physical harm, and to help prevent crisis and suicide. In health systems, we continue to see a mass awakening to to the importance of investing in and prioritizing employee well-being. The standards of the American Association of Colleges in Nursing (AACN; 2021), The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Education, a guide for the teaching standards of higher education, emphasize the importance of a nurse’s competency in promoting self-care and being able to lead in times of crisis (Zaccagnini & Pechacek, 2021). The guide supports the integration of these competencies into the curricula of nursing education and practice preparation, from didactic to practicum courses.

Teaching: A Platform for Change

Teaching is now my way of nursing, a space for me to lean into the opportunity to engage in authentic, caring moments, quality improvement work, and systems transformation—the parts of being a nurse I love most.

I began my academic career in 2023, teaching courses in the UMN School of Nursing that have spanned Integrative Health, public and community health, leadership, scholarly dissemination, and, now, health systems and care models in our Health Innovation and Leadership Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) program. As academic programs from across the nation transition their curricula to align with the competency requirements of the updated AACN Essentials, we have an opportunity to look at our ethos and some of our foundational values, and to integrate knowledge from other disciplines (e.g., social sciences, anthropology, humanities, arts, history, physics, and law), other ways of knowing, other world views. The embodied practical skills of healing and connecting requires immersive and perspective-shifting experiences. A global view of healing practices and the socio-cultural aspects of health are essential for today’s nurses and nurse leaders.

As a discipline, nursing evolved from the origins of healing traditions and art forms (Thornton, 2019). Presence, empathy, and deep listening must all be not only cognitively learned, but embodied and lived. The experiences and wisdom I have gathered in my time outdoors, studying the functions and qualities of the natural systems around us, led me to delve into the literature, studying the pedagogical designs, successes, failures, theories, and knowledge bases of others engaged in this work. I continue to learn so much from the thriving functions that are part of systems relationships: how trees work together, how the moon moves the water, how plants expand themselves to receive the sunlight. These inter-workings are here for us to notice, and our connection to them is fundamental to our health. Through such work, we reconnect with ourselves, relearn to regulate our systems, discover what to seek for nourishment, and accept the need for diversity and differences. This is work that will move all of us, across the world, to act to strengthen, reconnect, and heal our global community. For nurses, the socio-cultural aspects of our health are an area deserving of our assessment, attention, and intervention.

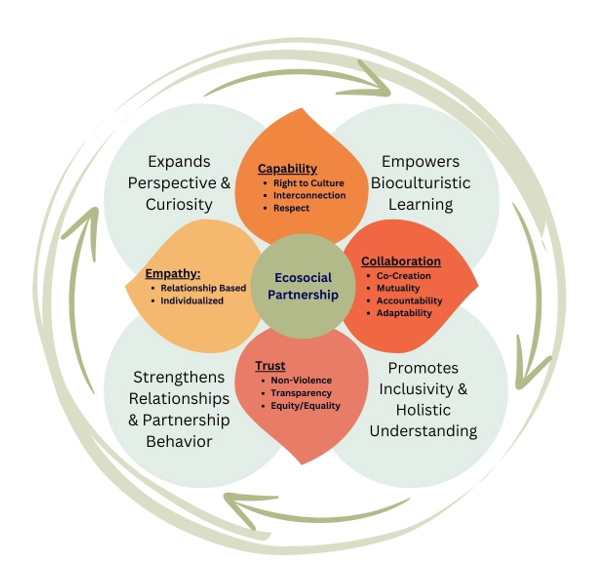

Regenerative Learning Systems

Learning systems are at the forefront of research within the health science disciplines, often drawing inspiration from the study of natural ecological systems. We are designing organizations which are structurally regenerative in nature (Vandvik & Brandt, 2020). Theoretical literature on how to translate these healthy functioning ecological structures into practice for redesigning our economic, entrepreneurial, and-health related systems is still in its infancy (O’Connor & Audretsch, 2023). With goals for a more holistic knowledge and practice base in nursing education, my colleagues and I adapted Krieger’s (2021) ecosociological embodiment theory into a framework for building regenerative and active learning systems that could empower partnership behavior and provide the structural support necessary for learning through multiple ways of knowing. Our Ecosocial Partnership Framework (Walton et al., 2024) introduces a value-based approach to social change and a theoretical foundation for the integration of actions that are adaptable based on context. The framework, illustrated in Figure 1, serves to support users in the process of cultivating learning systems which are grounded in values which honor the qualities of healthy and functioning regenerative cycles.

My goal in this essay is to unpack the Ecosocial Partnership Framework for Learning, looking at how it structures my work teaching nursing and allows me to introduce decolonial and international objectives in the nursing classroom.

Ecosocial Partnership

At the center of the model is the notion of an “ecosocial partnership,” sustained and reinforced by the leaves radiating from the core. This partnership is built of the innate qualities of living systems that alter their function, behavior, and capacity for growth. The social relationship humans have with and within the ecological environment system is inextricably linked with societal and social practices, behaviors, and structures. Each petal that peels out from this innate way of being in relationship is a quality—such as capability, collaboration, trust, and empathy—which makes the partnership possible.

At an even more granular level are the values which inform those qualities, including relationship-based but individualized interactions, an understanding of interconnection, the protection of culture, and respect. Weaving these practices together and embodying them in the learning environment invites greater curiosity and openness to learning through a diversity of perspectives. And in the design of this learning environment, it is important to integrate this openness with an invitation for all members of the system to co-create together; to share mutuality, responsibility, and accountability; and to learn from a diversity of cultures, philosophies, and mediums, including art forms of poetry, embodied practices of nervous system regulation, and ways of connecting socially through the senses.

Our model takes what we consider to be important to an optimal healing environment, and applies it to the environment necessary for inclusive learning, one which promotes connection, agency to engage in social change, and holistic behaviors. It is about shifting from the iterative approach of constant information consumption and generation to the experiencing of information as it comes, and building new innovations from it. The ancient is a part of our whole, and in this model, we approach wisdom in the design of our new ways of thinking, being, and knowing. Our aim is for students to fully learn and then regenerate or embody their acquired wisdom into new ideas in order to respond to the complexities of today’s population and planetary health conditions with optimism, creativity, engagement, and understanding.

When an environment of trust—one that includes non-violence, transparency, and practices of equity—is promoted, diverse ways of knowing become the foundations of a more symbiotic and holistic way of conceptualizing multiple truths or possibilities of co-existence. This area of the work includes self-reflection and assessment of biases. Coming to approach the understanding and acceptance of multiple differences with empathy makes us stronger partners, and allows us to continue learning and creating together in a regenerative way.

Given that we as individuals are each complex learning systems informed by social experiences over the evolution of our life, I want to share that the learning framework in Figure 1 has developed from what I’ve experienced and learned during my life, beginning with a magnolia tree that was a central part of my childhood. A tree living and, well, giving in the front yard of the house in which I was born, it received my questions and wonderings about the confusing complexities of my home environment as I sat in front of it, studying its textures with my hands. One might assume that this was a safe and gentle place in which the tree taught me to root myself, but that wasn’t the case. When I was four, the tree taught me to build a swing, to move, to feel the wind, and to take agency in the experience of my own joy. Looking back, I credit that tree with creating in me the roots of this project.

A life of both academic study and ongoing experiences with some of the more challenging sides of the natural world have privileged me to truly feel the relationships we are able to have in this lifetime. And as time goes on, I learn even more deeply that these relationships are the crux of our planet’s health and sustainability. Ecosocial partnership is more than just the defining place or role humans hold within the ecological system. It is the social relationship humans innately have with all life, including self. To be a socially integrated partner with the environments in which we exist means to practice living and behaving in ways that are respectful, caring, and empathetic with all the living entities that make up our world. It is to remove ourselves from the top tiers of the ecological pyramid and see that we are each integral to the function and future of this beautifully complex, multidimensional planetary system.

The values that coat the petals of each area in the illustration help in the design of a teaching environment that promotes the learning experience. They inform an instructor’s approach to setting the rhythm of the class, starting with social bonding and relationship-building activities such as introductions, “get to know you” break outs, and opportunities to engage in dialogue. Building partnership within the group is important in creating the sense of trust, belonging, responsibility, accountability, and agency that enables each student to engage. The values also underlie how I introduce myself to a group at the beginning of a semester and how I share my own story. Relationality is key for sustaining connection between systems within the environment. The integration of active learning opportunities to regulate students’ mind-body systems, reduce stress, and support their sense of presence and self-awareness is a critical aspect of the approach. Learning these types of skills can empower nursing students with tools to reclaim supportive practices and behaviors in caring for their own bodies. This often involves competence, knowledge, and skill building in lifestyle behaviors such as breath, movement, food, sleep, rest, reflection, and creative practices. Weaving these exercises into assignments, learning activities, and the overall approach to teaching has great potential in supporting the development of an environment where students can flourish.

Curiosity, Empathy and Forgiveness

At the top left of the diagram, we begin with the cultivation of curious inquiry, as this is integral to what science is—a way of knowing about the world (National Academy of Sciences and Medicine, 2016). In Dynamics of Human Biocultural Diversity: A Unified Approach (2013), Sobo explains nature as the “here and now”—the aspects of our living systems that inform this collective experience; each of our genetically informed states of being in relationship with the external environment; and the history and stories of the living systems within it. She explains the internal and external as being in a constant dance with one another, fully working as synergistic interactions. In a holistic point of view, systems can only exist and function in their fullness when connected and in a healthy, dynamic relationship. Sobo challenges readers to see the interdependence of all systems, no matter how large or small.

To cultivate curiosity, we must ask questions, hypothesize, attempt, measure, evaluate, and share perceived ideas. As shown in the top left of the diagram, we do this by asking questions in a safe environment when students first meet each other. We ask about students’ feelings, fears, and expectations coming into the program. We can measure and evaluate similarity in responses to experiences and questions using technology to promote relational awareness and build live connections in the classroom. We guide the practice of modeling empathy and capability in the way we structure the class plan and our learning activities. In addition to the cognitive aspects, curiosity inspires our sensory experiences and processes for acquiring knowledge of the environment. Think back to when you were a child, for instance, and to your desire to understand what the tree felt like, to reach out and touch it. Or when your quest to experience the scent of a flower called you to bend down and smell it. Curiosity, in its free-flowing and creative state, allows us to explore, to notice patterns and connections, developing our ability to explain the relationships between variables (Nassehi, 2024).

This curiosity is one of our most authentic and wild qualities as human beings. As developing children, our sensory experiences and the feelings we carry within us inform our questions and therefore our personal discovery of the world. Theory, values, philosophical reasoning—these are humble states of wonder about life that influence how we behave and what we believe in. Without wonder or inquiry, we would feel stuck and our systems would stagnate. We would become observant judges instead of curious teachers and learners. Learning should be regenerative for each of us, and never stop. Research even indicates that continual learning throughout life is important to our health.

In our wilder state, learning about our environment was necessary to our survival, but our awareness was focused on risk, safety, and protective instincts, keeping our fight or flight system active. Now, however, heightened awareness is not necessarily about keeping our nervous systems regulated and our internal environments in healthy balanced states, bit is instead about what we give our awareness to. Awareness of the complexity of the life of a fern for example, gives us more understanding and empathy for a living being other than ourselves. The stories behind how we present ourselves—what we say, how we say it, what we eat, the music we listen to, the way we dress, the perspective we have on an issue, the paradigm in which we live—affect how we socially receive one another. Starting from a position of “not knowing” instead of “knowing” is key.

I was born into a family unit with deeply unhealed generational patterns of pain and suffering. I recall the exact moment in the midst of chaos and discord when I decided to be curious about the patterns I was sensing around me. I must have been no older than five or six when I started to see threads in the behaviors and experiences of the people within my environment, threads like substance dependency, pain, anger, neglect, abuse, loss, suffering, and loneliness. My understanding of how and where those threads connected with one another took years of personal learning and study, but I recall having a deep interest as a child in trying to connect the humor, charisma, strength, optimism, and humility that I consistently saw and felt as well.

I began to realize that these elements all informed one another and were almost omnipresent in the wholeness of both one individual person and a fully complex community. It was enlightening and inspiring to know that this coexistence was not only possible, but was perhaps one of the most vibrant and real expressions of living. This was a pivotal perspective for me to reach as a child while navigating the conditions I faced. It informed my mental model around consistency. I was commonly in the journey of finding a new roof to live under, a sofa to sleep on, food to eat, people to trust, ways to get to school, places to be inspired by, music to listen to, trees to touch, streets and studios to dance in, joy to experience, and opportunities to continue learning and, later, leading. This dynamic way of growing up gave me the opportunity to cross paths with many individuals, families, and communities who changed my worldview.

It also gave me the chance to develop a practice of forgiveness and letting go—a practice still integral to how I approach the world of relationships and both express and receive care. Sharing the value of empathy as visualized in the model, together with the value of instilling capability, opens up space for weaving in active practices of forgiveness and letting go, which are important in building empathetic capacity. I believe that the ability to let go and to reduce reactivity can be developed in students, and ultimately within all of us. We can build and demonstrate competency through the practiced behavior of acceptance and mutual respect, using active learning scenarios in which mutual respect is practiced and developed as an emotion-informed behavior. When respect is embodied, we assume responsibility for our own responses and take accountability to know and express how we feel. Incorporating this approach into dialogue and examples helps students understand the security is necessary in the relationship we have with ourselves, and its influence on the empathetic inquiry we are able to develop and maintain for others.

An individual’s relationship with their personal stories is foundational in this framework. Each person has unique sociocultural and generationally informed stories that influence their cell structures, behaviors, and various expressions; these are central to our own personal biases and to the value we place on our ability to empathize with one another. The work of social epidemiologist Nancy Krieger (2021) has led to advanced discoveries in the role our embodiment pathways play in the social aspects of how we function both as individuals and as collective societies. Knowledge of these pathways and of Krieger’s (1994; 2005) ecosociological theory are foundational in the application and translation of our learning framework.

Bioculturistic Learning, Ecosociological Theory, and Embodiment Pathways

Ecosociological theory looks at the relationship of human development, health, and behavior patterns to the social experiences human cells have encoded or adapted to over time (Kreiger, 2001). These cellular adaptions intersect an individual system’s function and risk for disease. Kreiger’s work with embodiment pathways began in 1979 with her book Embodiment: A Conceptual Glossary for Epidemiology, and has since pushed advancements in understanding the impacts of social discrimination and determinants on health (Hittner & Adam, 2020). Social experiences and relationships have a direct impact on our health and on our well-being as a society, affecting the ways in which we interact with each other and the world. In applying Krieger’s (1994) theory to the changing behavior patterns of human interaction with the ecological environment, it becomes evident that emphasis on recalling these social relationships and experiences has value in our direction toward a more partnership-oriented society.

Biocultural diversity is the union between biology and culture within an ecosystem which informs life (Sobo, 2016; Bridgewater et al., 2019). Bioculturism, then, helps us understand the influence of culture on our social and biological dimensions of health. Incorporating it into our social models involves practicing an approach which brings us further into a more inclusive and holistic way of being in reciprocal relationships with each other as global partners.

Krieger’s ecosociological model (1994) gave grounding direction to the knowledge of embodiment pathways, helping bridge gaps in understanding how peoples’ environmental and social experiences influence their neuro-behavioral development. It also helped advance scientific understanding of social impacts on the epigenetic expressions of learning, memory disorders, stress responses, stability, cognition, and affective conditions (Meloni & Reynolds, 2021; Ginsburg & Jablonka 2018). Evolving knowledge within this area of research is applied in the psychosomatic field disciplines (Fava et al., 2017), and is the basis of interventions that develop an individual’s learning through experiences which require shifting from environment sensing to physical body sensing to internal sensing (Kroner et al., 2015). In the humanities, the field of psychosomatics is explained as a discipline evolved from the studies of mind-body dualism (Kirmayer & Gómez-Carrillo, 2019). Psychosomatic theory, research, and practice see the mediation among biopsychosocial factors, and address these dynamic parts holistically in practice.

When we started to apply some of these embodiment methods to foster connection and relationship with environment within our learning systems in nursing education, we found ourselves calling into question some fundamental concepts. One, for example, was the idea of where intelligence lives within the body. Advances in the fields of neuroscience and psychoneuroimmunology have challenged the association of “mind” with the brain organ, expanding the idea of the mind to a full-body system (Danese & Lewis, 2017). We found that there is value in discussing the interpretation of the conscious learning mind, and that the generalized conceptual paradigm may need to shift to align with the modern scientific evidence supporting intelligence as being found within the fullness of the body system. (This could be an area of further study and research—examining cognition as actually extending into the gut microbiota and myofascial loose connective tissues which interlink the entirety of the organ systems (Chew et al., 2023)).

Some argue that the body in its wholeness is best understood as the biological nature of cognition (Lyon, 2017). Further scientific understanding in this area could completely shift the way education systems measure and balance the efficacy of cognitive teaching strategies with somatic learning. Meloni and Reynolds state that,

if cognition is held to be embodied in the whole organism rather than being fundamentally in the brain—and as being extended into the physical, social, and cultural environment—then a biological account of this structural coupling at the cellular and neuronal level appears important to any such argument. (2021, p. 2)

With decades of evidence and theory to support the integral nature of social connection on humans’ health, well-being, and behavior patterns, the necessity for environments to be designed with these values in mind in order to foster stronger experiences of connection is essential. In the application of this social engagement work in the global context, a holistic approach to the integration of experiences and knowledge that will support a shift in behavior practice toward partnership is another core element of our framework.

Holistic Learning and Strengthening Relationships

We acknowledge a diversity of wisdoms that have value in practice. A regenerative learning environment structure should be designed to include those perspectives, with inclusive design of learning system content including a more holistic and global worldview. Here, a learning system refers not just to an educational classroom, but to any shared environment in which learning is exchanged. It is an environment that is built and carried out in action, and aims to foster relationships among the systems within it. In the effort to focus on the reconnection of social relationships with all members of the ecological community and the way of seeing self as part of that community, a framework that encourages an internationalization of global knowledge bases, without domination of one, is paradigm shifting.

Imagine what learning about a single concept through multiple socio-cultural realities can bring to one’s understanding of the greater holistic experience of life. As an example, while I was graduate student I studied the physiology of body temperature regulation, primarily through biomedical language but also through more eastern-based viewpoints such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Tibetan and Ayurvedic systems. Looking at the same topic from these different perspectives expanded the ways in which I understood the interconnections of temperature regulation with our day-to-day experiences, energy levels, eating habits, and behaviors.

In the western model, the physiologic process of body temperature regulation, or thermoregulation, is generally explained as the control of our internal body temperature by particular areas of our brain in communication with receptor sites in the body (Romanovsky, 2018). The Taoist theory of Yin and Yang, in contrast, sees body temperature regulation through a different perspective. This theory, rooted in the work of Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu, sees life as a system of constant exchange between complementary and opposing forces (Wang, 2022)—life and death, negative and positive, empty and full, hot and cold. It connects the composites of life’s polarities as experiences of constant exchange and change. Here, hot and cold are beyond brain and receptors, and related more to food relationships, daily energy movement practices, and breath technique.

Application of the bioculturistic approach to learning opens our perspectives to more holistic thinking. In nursing and the health sciences, I believe that this would support our shift from a treatment-driven approach to a prevention-driven one, on both the individual and community levels.

Learning from a diversity of vantage points often leads to understanding a concept with greater breadth and depth. Consider if this were translated to the way we as a global society learn about some of our similar experiences—the functions of the nervous system, our energy systems, breath regulation, agriculture, food, architecture, engineering, perhaps movement or health promotion practices. This could change everything about the ways in which we interact with ourselves, our families, and our local communities, and about how much we rely on institutionalized medicine or pharmaceuticals for issues that could be safely and effectively managed with food and lifestyle practices. Children across the world should have the opportunity to learn about and know their bodies, as well as how to support themselves and create optimal conditions for their health; this should be knowledge we share with each other as members of the global community. These social changes that have the potential to completely alter our relationships and interactions with the environment, and to emphasize the strong relationship between human system and planetary system health. With a more holistic understanding, we practice greater partnership with transparency, equity, and equality embedded in our structure. And with that strengthened partnership, our regenerative learning can continue to expand and evolve.

Applying the Framework to Internationalization

In our application of this framework in nursing education, we used many mediums for learning and strengthening connections, including poetry, painting, music, movement, and even improv to understand concepts of leadership, diversity, sustainability, and advocacy. For example, to introduce mental models, liberation structures for decision making, and the importance of shared visions among diverse teams in leadership development, we had students process what they were learning in an active way. We introduced scientific terminologies of biomimicry and systems ecology to weave in conversations about biodiversity and planetary health. Students engaged in an activity where they identified the problem-solving qualities of another living being with which they identified (i.e., a mountain, water, a wolf, a flower). Responses were analyzed and groups of common themes were quantified and presented back, so students were able to see the different trends. They were then prompted to mix and mingle in the classroom to meet with others who identified as being in a different group. Our prompt guided conversations focused on identifying one another’s unique gifts and strengths.

We invited a Buddhist nun to guest lecture on Buddhist interpretations of the leadership styles we were studying, used poetry or stories in class sessions to ground the students, and introduced psychosomatic concepts of movement practices. We had moving discussions about relationships to nature that broadened students’ awareness of themselves as being a part of nature. Many expressed feeling empowered by the new awareness of their impact on systems. And through their group projects, students gained new appreciation for diversity in the sustainability of healthy systems, from local to global scales, discussed the value of diversity among team members, and evaluated areas within their own working groups for which a different voice or strength might have been valuable.

Taking into account the many different relationships we each have with land, food, music, and culture, one of the most important starting applications of the framework is guiding individuals through a reflective practice about their own ecosocial relationships, with time to share and discuss their discoveries with others. This allows students to collectively recognize the complexity of differences and similarities among us. We facilitated this reflective practice at a national nursing conference, with participants remembering, for instance, the impact of guava trees from their childhood, or healing traditions using herbs from their native lands. Some participants were drawn and called to similar places. After personal reflection, each was able to share and help support the others in thinking about ways they might be able to integrate some of these qualities into their lives in order to foster a stronger sense of connection.

If the framework is being used to foster deeper connections within groups or internationalized spaces, music, art, and other creative forms can support the development of opportunities for participants to experience bonding despite sociocultural differences. The creation of inclusive learning communities is the result of grounding our design and innovation strategies in values driven by partnership. With a holistic and embodied approach to applying the framework, we can promote a stronger sense of curiosity, and stronger relationships based on deeper empathy.

A Decolonized Aim

To build an inclusive learning system which embraces the possibilities of multiple ways of being, we must prioritize an integration of strategies and cultural frameworks for understanding. And we must note the decolonial emphasis of this framework. Sylva and Persia (2024) emphasize that internationalization work in higher education must have an aim of decolonization and be appraised through critical perspectives to avoid neoliberal and colonial orientation. With our framework designed to support development in the behaviors of partnership, our intention is to break through the patterns of historically sustained hierarchies of oppressive relations with other ways of knowing in nursing and medicine.

We are not aiming for individuals to become an experts in a practice of traditional origins from a culture outside of their knowledge. Rather, our aim is to expose all learners to diverse ways of knowing and mediums for learning, enabling them to work through an authentic practice of self-awareness and identify their personal biases to enhance their state of empathy and their sense of curiosity in their approach to relationships.

Through this approach, we aim to better ground nursing students in their own ethos and value systems. In a rapidly changing practice world, the speed of production continues to change transactions between nurses and patients, translating to more generalized practice models and treatment approaches. Some of the most impactful health systems in the world today are those of nations with far fewer resources but far more embodied values and ethics in their ways of being.

As members of an international profession, nurses have a global position in the planet’s health ethos. The position statement of International Council of Nurses (ICN; 2018) strongly supports nurses’ commitment to addressing climate change. Rosa and colleagues (2019) discuss the need for nurses to look through the lens of global citizenship and advocate through education. Throughout history, nurses have been innovators in the advancements of public health, disease prevention, and health promotion. Today, they must be well prepared in the complex sociocultural implications of health and disease inequities in order to fully partner with patients in the delivery of care plans unique to both individuals and their communities. The treatment model which generalizes interventions for common symptoms to a limited common practice of pharmaceutical delivery is not sustainable. We must emphasize the necessary knowledge of essential food relationships and healthy living practices through movement and breathing, connection building, and nervous system regulation, not only in families and households, but in classrooms and offices. Values-based systems, rooted in partnership behaviors, can help prepare nurses to be fully present with their patients, acknowledge their own knowledge gaps, and partner in the co-creation of supporting their patients into optimal conditions for health and flourishing.

The process of pathogen colonization of the gut microbiota can result in disease symptoms such as skin disorders, immune dysfunction, cognitive decline, and anxiety (Goel et al., 2022). In this sense, colonization is equivalent to the concept of domination—a hierarchy of takeover versus shared experience. In today’s nursing education and practice, we often overlook the very art of healing in which the discipline is rooted. The healing traditions of cultures across the world can inform our knowledge of therapies and interventions we know to be of significant importance to health and healing. To empower the nursing discipline with the knowledge it once shared with society about the true value-based approach to healing relationships and environmental conditions, a globally based paradigm should support the way nurses learn about evidence-based interventions. With greater capacity and interest to learn of those differences, a practice of respect, acceptance, and value for any individual or group using a differing practice or knowledge system can be embodied and better supported.

Conclusion

We exist in a time when socio-political systems and structures are in some ways turning in on themselves, emerging to become something new to our consciousness. Over the last three to four decades, science has brought concepts of complexity, patterns, networks, and systems to the forefront (Capra & Luisi, 2014). As integral members of the ecological system, partnership is ingrained within us. Social engagement and our sense of connection are critical to our survival. As displayed in Figure 1, a socially sustainable process is one which can continue to grow and evolve; our hope for this work is to focus on adding value rather than solving problems. The outcome of a regeneratively structured learning framework will, by nature, help address problems as they arise, but with a value-focused approach the application can remain adaptable and fluid based on context and need. Embodied learning requires an environment of established trust and safety, where individuals feel the invitation to co-create and explore with open curiosity. When partnership values are embraced in social practice and in the design of human led learning systems, opportunities for bioculturistic perspective to shift behavior are enhanced (Walton et al., 2024), supporting our global efforts toward a more internationalized, knowledge-based world.

References

An, M., Heo, S., Hwang, Y. Y., Kim, J., & Lee, Y. (2022). Factors affecting turnover intention among new graduate nurses: Focusing on job stress and sleep disturbance. Healthcare (Basel), 10(6), 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061122

Bridgewater, P., Rotherham, I. D., & Rozzi, R. (2019). A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People and Nature, 1(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10040

Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge University Press.

Chew, W., Lim, Y. P., Lim, W. S., Chambers, E. S., Frost, G., Wong, S. H., & Ali, Y. (2023). Gut-muscle crosstalk: A perspective on influence of microbes on muscle function. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 1065365–1065365. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1065365

Danese, A., & J Lewis, S. (2017). Psychoneuroimmunology of early-life stress: The hidden wounds of childhood trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.198

Davis, M. A., Cher, B. A. Y., Friese, C. R., & Bynum, J. P. W. (2021). Association of US nurse and physician occupation with risk of suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry, 78(6), 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0154

Fava, G. A., Cosci, F., & Sonino, N. (2017). Current psychosomatic practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000448856

Ginsburg, H., & Jablonka, E. (2018). The evolution of the sensitive soul.MIT Press.

Ge, M., Hu, F., Jia, Y., Tang, W., Zhang, W., & Chen, H. (2023). Global prevalence of nursing burnout syndrome and temporal trends for the last 10 years: A meta‐analysis of 94 studies covering over 30 countries. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(17–18), 5836–5854. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16708

Goel, G., Requena, T., & Bansal, S. (2022). Human-gut microbiome: Establishment and interactions. Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier.

Hammig, O. (2018). Explaining burnout and the intention to leave the profession among health professionals: A cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 785.

Hittner, E. F., & Adam, E. K. (2020). Emotional pathways to the biological embodiment of racial discrimination experiences. Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(4), 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000792

International Council of Nurses [ICN]. (2018). COP27 November 2022 – How ICN is addressing climate change and planetary health. https://www.icn.ch/news/cop27-november-2022-how-icn-addressing-climate-change-and-planetary-health

Kirmayer, L. J., & Gómez-Carrillo, A. (2019). Agency, embodiment and enactment in psychosomatic theory and practice. Medical Humanities, 45(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2018-011618

Krieger, N. (1994). Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Social Science and Medicine 39, 887-903.

Krieger, N. (2005). Embodiment: A conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979), 59(5), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.024562

Krieger, N. (2021). From embodying injustice to embodying equity: Embodied truths and the ecosocial theory of disease distribution. In Krieger, N. Ecosocial theory, embodied truths, and the people’s health. Oxford Academic. https://doiorg.ezp3.lib.umn.edu/10.1093/oso/9780197510728.003.0001

Lyon, P. (2017). Environmental complexity, adaptability and bacterial cognition: Godfrey–Smith’s hypothesis under the microscope. Biology and Philosophy, 32(3), 443–465.

Meloni, M., & Reynolds, J. (2021). Thinking embodiment with genetics: Epigenetics and postgenomic biology in embodied cognition and enactivism. Synthese (Dordrecht), 198(11), 10685–10708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02748-3

Nassehi, A. (2024). Patterns: Theory of the digital society (1st ed.). Polity Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Science literacy: Concepts, contexts, and consequences. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23595

O’Connor, A., & Audretsch, D. (2023). Regional entrepreneurial ecosystems: Learning from forest ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 60(3), 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00623-8

Pradas-Hernández, L., Ariza, T., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Albendín-García, L., De la Fuente, E. I., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A. (2018). Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 13(4), e0195039–e0195039. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195039

Ren, H., Li, P., Xue, Y., Xin, W., Yin, X., & Li, H. (2024). Global prevalence of nurse turnover rates: A meta‐analysis of 21 studies from 14 countries. Journal of Nursing Management, 2024(1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5063998

Romanovsky, A. A. (Ed.). (2018). Thermoregulation: From basic neuroscience to clinical neurology. Part I. Elsevier.

Rosa, W. E., Dossey, B. M., Watson, J., Beck, D. M., & Upvall, M. J. (2019). The United Nations sustainable development goals: The ethic and ethos of holistic nursing. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 37(4), 381-393.

Silva, K. A. da, & Pereira, L. S. M. (Eds.). (2024). Decolonizing the internationalization of higher education in the Global South: Applying principles of critical applied linguistics to processes of internationalization. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003409205

Sobo, E. J. (2016). Dynamics of human biocultural diversity: A unified approach. Routledge.

Southwick, S. M., & Southwick, F. S. (2020). The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout: Applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. Archives of General Psychiatry, 77(5), 449–450. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4800

Thornton, L. (2019). A brief history and overview of holistic nursing. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, 18(4), 32.

United States Surgeon General. (2022). Framework for workplace mental health and wellbeing. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Vandvik, P. O., & Brandt, L. (2020). Future of evidence ecosystem series: Evidence ecosystems and learning health systems: Why bother? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 123, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.008

Walton, A. (Author & Presenter). (January 19, 2024.) “Transformative models of partnerism found in nature as innovative pedagogy for advancing improvements in higher education, nursing, & health.” American Association of Colleges in Nursing (AACN) Doctoral Education Conference. Naples, FL.

Walton, A., Beese, S., Chesak, S., Gingerich, S. D., & Wilson, R. (2024). A partnership perspective on ecosocial reciprocity for cultural transformation. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 11(1), 5-. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v11i1.6121

Wang, K. (2022). The Yin-Yang definition model of mental health: The mental health definition in Chinese culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 832076–832076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.832076

World Health Organization [WHO]. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International classification of diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

(2018). Decade for health workforce strengthening in the South-East Asia Region 2015–2024; Second review of progress, 2018. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/274310.

Zaccagnini, M. E., & Pechacek, J. M. (Eds.). (2021). The Doctor of Nursing Practice essentials: A new model for advanced practice nursing (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

-

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

↵