Roots and Transformations

Internationalizing the Curriculum and Campus through Global Engagement

Dennis Falk

I was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1948, and I grew up knowing very little about the world outside of northern Minnesota. That changed in 1966, when, as a student at Macalester College in St. Paul, I became immersed in a campus that had internationalism as a core value and where I participated in two very different experiences that encouraged a global perspective. I went on to have an array of opportunities to learn about the world and to share what I learned with others.

In this essay I explain how my background led me to become more globally aware, and describe a number of international opportunities that led to me teaching courses on global issues, participating in a national activity to “Educate Globally Competent Citizens,” and co-leading an effort to internationalize the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) campus. Throughout, I benefitted from (and hopefully contributed to) my involvement in the University of Minnesota’s Internationalizing the Curriculum and Campus initiative.

Background

Growing up in a “streetcar” neighborhood in Duluth, I had a very limited view of the world, venturing out of my home neighborhood only on weekends when we visited my grandparents, who lived about four miles away. My focus was on sports, and my knowledge of the world was limited during elementary school to what I learned in the Weekly Reader, and later to what I might view in Time magazine on the way to the sports section.

Those exposures must have had an influence, though, because when I started to look for colleges, I was attracted to Macalester partly because the basketball coach said he was working on a trip to the Soviet Union. (It was aspirational. He was also trying to line up some games in Hawaii. We did play in Florida, Arizona, and California.) I played basketball at Macalester for three years, from 1967 to 1970. I was also involved at Mac in others ways.

Macalester has long had a strong focus on internationalism, as indicated by its pride in being the first college or university in the United States to fly the United Nations flag and by its provision of easy opportunities to engage globally. In the summer of 1969, I went to Europe for three months, learning almost as much in that time as in my four years on campus. I worked at Selection du Reader’s Digest in Paris during July, leaving the months of June and August to travel.

During June I traveled by car with friends. In Czechoslovakia, I was pulled over by a guy in a military uniform with an assault rifle, two miles into the country. The guy had a little book with various languages, and after a couple of false starts, concluded that English was the language of choice. He flipped to a page that said that we were driving too fast in a built-up zone, and asked me, as the driver, how we pled. Another page of the book explained that if I pled guilty, we could give him half of the Czech currency we had just changed at the border. If I contested, we would have to go to the police station and await our hearing, which could take days. We paid our fine, as did every other driver of a car with a foreign license plate. I realized that I was in a different world.

During the summer of 1970, I participated in another international program offered by Macalester, Ambassadors for Friendship. This program selected two domestic students to drive four international students around the United States. We were given a big station wagon, a gas credit card, $300, and a list of families with whom we could stay, with the idea that we should experience the U.S. We drove 14,000 miles in six weeks, traveling across most of the states west of the Mississippi and through three provinces in Canada. Seeing so much of the U.S. and Canada through the eyes of students from Bolivia, Argentina, Chile, and Hong Kong opened my eyes to different cultures and perspectives. I was happy to follow in the footsteps of former United Nations Secretary General and Nobel Laureate Kofi Annan, who had participated in the Ambassadors program about a decade earlier.

I entered Macalester in 1966 having lived entirely in the U.S. and having visited only four states. I left in 1970 having lived and worked in Paris for one month and travelled for two months to 13 countries in Europe. I had also travelled to 32 states and three Canadian provinces, many of them with four international students. Those four years broadened my perspective and knowledge of the world immensely.

I also met my wife at Macalester. In 1976, we took a six-week honeymoon in Europe, including 10 days in the Soviet Union— an experience which reinforced for us the immense impact of the political, economic, and social dynamics in different countries. I wanted to further understand those differences.

Beyond Macalester, perhaps the most important part of my background was teaching in 1984 as part of a UMD Study in England Program, which brought UMD students and faculty to the UK. After class, the students would often go out to the pub with their UK contemporaries from the UK, and my American students reported being unable to participate knowledgeably in conversations about what was going on in the world. Some didn’t seem to know what was going on in the U.S. as well as their UK peers. This was a big motivator; I wanted UMD students to be at least as knowledgeable as the peers they met and studied with in the UK.

I arrived at the University of Minnesota Duluth in 1977 with a set of experiences that inclined me towards doing things internationally and globally. I started teaching global content, and later opportunities led me to engage in international activities at both the campus and national levels.

Teaching Global Content

I was attracted to UMD’s School of Social Development, with its focus on social change and its international priorities. A colleague, originally from India, developed an undergraduate liberal education course on Global Issues, in part as a way to generate student credit hours for a unit that offered only a graduate program with relatively small classes. That professor left UMD in 1985, and I volunteered to teach the course, SW 1210 Global Issues, which had the following description: “Global problems of war, peace, national security; population, food, hunger; environmental concerns, global resources; economic and social development; human rights. Examines issues from a global problem-solving perspective. Value, race, class, gender differences.” Many of the students who came to this course were likely attracted to the topics, but also wanted to meet Liberal Education requirements. Most came with limited knowledge or experience with global issues, much as I had when I started college. I felt satisfaction in helping them adopt a more global perspective, become more knowledgeable about international topics, and gain skills that could be used to continue to enhance that knowledge of the world.

I taught global issues courses at UMD for over 30 years, and in many different ways. In 1991, when UMD’s Continuing Education program wanted to begin developing online courses, I developed a web-based offering of Global Issues. The in-person course evolved into a First Year Experience course in the late 1990s, and into an Honors Course in 2004 when UMD was developing its Honors Program. In 2016, I integrated global issues content with student success knowledge and skills in a course titled “EHS 1000 Into the World.” I also had the opportunity to teach the Global Issues course three times in England, including with students from the University of Worcester. One of my great joys is that the global content and teaching methods I developed have been used by people with whom I’ve taught as they move to other programs and campuses.

I retired from UMD in 2017, but have continued to teach about global issues in UMD’s University for Seniors Program, with four in-person courses on global topics before the pandemic, and similar topics via Zoom in the past three years. The nature of global challenges continues to change, but teaching students with 50+ years of knowledge, experience, and travel is rewarding. And on top of that, there are no grades or grading.

Global Engagement Project

As I taught global content over the years, I became more interested in research into the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for students to become “globally competent” and into how this competence could be achieved. I had been awarded a sabbatical to explore these issues during the 2006–2007 academic year when UMD’s Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs called me one afternoon and asked “Can I buy you a cup of coffee?” I approached that meeting with some apprehension, but he invited me to become involved in one of the most meaningful activities of my professional life, known first as the Seven Revolutions Initiative and later as the Global Engagement Initiative.

In the fall of 2006, I began working with The New York Times, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) American Democracy Project to create the Seven Revolutions Initiative. The name arose from a framework developed by Erik Peterson, who, working with other leading policy analysts within CSIS, identified the seven global forces (“revolutions”) expected to most impact the world in the next 20–25 years: population, resource management, technology, information, economics, conflict, and governance.

The group’s first activity was to identify the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of a globally competent citizen. Toward that end, I interviewed 22 individuals who were identified by 10 key academic administrators at participating campuses as most knowledgeable about this topic. We summarized their responses, and concluded that the following outcomes would guide our project:

Knowledge. Upon graduation, globally competent students will be able to:

-

- Describe important current events and global issues (e.g., environmental, economic, political, health, population).

- Understand and analyze issues and events in the context of world geography.

- Explain how historical forces impact current events and issues.

- Describe the nation/state system with its strengths and limitations.

- Describe cultures from around the world, including religions, languages, customs, and traditions.

- Identify transnational organizations (e.g., NGOs, multinational corporations) and their impact on current issues.

- Explain the interdependence of events and systems.

- Describe how their own culture and history affect their worldview and expectations.

Skills. Upon graduation, globally competent students will be able to:

-

- Obtain relevant information related to the knowledge competencies listed above.

- Analyze and evaluate the quality of information obtained.

- Think critically about problems and issues.

- Communicate effectively verbally and in writing.

- Communicate and interact effectively across cultures.

- Speak a second language.

- Take action to effect change, both individually and with a team.

Attitudes. Upon graduation, globally competent students will be predisposed to:

-

- Be open to new ideas and perspectives.

- Value differences among people and cultures.

- Be intellectually curious about the world.

- Be humble, recognizing the limitations of their knowledge and skills.

- Reflect on their place in the world and connection with humanity.

- Engage in an ethical analysis of issues and have empathy for their fellow human beings.

- Feel a sense of responsibility and efficacy to take action based on ethical analysis and empathy (Falk, Moss, & Shapiro, 2010, pp. 3–4).

With the goal of educating globally competent citizens at AASCU institutions, faculty from 10 of these institutions (including myself and Bill Payne from the University of Minnesota Duluth) decided to use the seven revolutions framework to develop curriculum. We shared teaching materials and resources to develop courses on our home campuses that could meet the identified learning outcomes, CSIS provided resources oriented to college and university students, and The Times organized these resources into templates within the Epsilen Learning Environment, a comprehensive course management system.

To expand the project’s impact, in 2010 we created a monograph titled “Educating Globally Competent Citizens: A Toolkit for Teaching Seven Revolutions,” which provided background information, summarized key content, and compiled three years of campus case studies, teaching and learning materials, and teaching resources. We published a hard copy, created a PDF version that could be downloaded free of charge, and offered workshops around the country to share information from the Toolkit and other resources with college and university faculty members.

CSIS left the project in 2012, the Seven Revolutions Initiative was re-named the Global Engagement Initiative, and the blended learning course was renamed “Global Challenges: Promise and Peril in the 21st Century.” Additional products of the initiative included 2nd and 3rd editions of the Toolkit and an e-book with content related to global challenges.

The Global Engagement Initiative is, in its own way, a statement of the unique power possible when individual scholars from campuses across the United States come together with passion. Perhaps it exemplifies one of the ways in which the Power of One can be amplified.

Planning for Comprehensive Internationalization on the UMD Campus

UMD was selected to participate in the American Council on Education (ACE)’s Internationalization Laboratory Cohort in 2012. At UMD, Leigh Neys, former Director of the UMD International Education Office, and I co-chaired the Internationalization Leadership Team (ILT), which conducted a review of international activities at UMD, identified campus goals and student learning outcomes related to internationalization, and developed a systematic plan for comprehensive internationalization at UMD.

This plan was aligned with the UMD Strategic Plan, which had been completed three years earlier. UMD Global 2020: Strategic Plan for Comprehensive Internationalization was completed in 2015, and included the following elements related to internalization:

-

- UMD’s Global Mission Statement defined our purpose for being, succinctly stating why the institution exists as that purpose relates to internationalization.

- UMD’s Global Vision Statement described our ideal future and the institution’s aspirations related to internationalization. It guides institutional decision-making and priority setting. The year 2020 served as our target for achieving this new vision.

- UMD’s Internationalization Campus Goals defined the six major initiatives leading to the realization of our new vision. These goals aligned with the UMD campus goals and focused on the primary programs and activities for moving us forward within the next three to five years.

- UMD’s Global Engagement Student Learning Outcomes described the knowledge, skills and attitudes we are seeking for UMD student graduates. (These outcomes were adapted from those identified in the Seven Revolutions/Global Engagement Project.)

- UMD’s Internationalization Campus Action Plan delineated specific, concrete steps for achieving the six goals. Some were short term, to be completed within a year or two, while others were longer term, intended to be accomplished over a period of several years.

The Global 2000 plan for comprehensive internationalization contributed to UMD’s reaccreditation and provided guidance for UMD’s internationalization efforts for several years. Changes in personnel and campus funding challenges have, however, limited full implementation of this plan.

Impact of Internationalizing the Curriculum and the Campus Activities

I had the privilege of participating in many of the University of Minnesota (UMN) Internationalizing the Curriculum and Campus (ICC) programs and activities, which impacted all of my work related to internationalization. My first ICC involvement was as a participant in an “Internationalizing the Undergraduate On-Campus Curriculum” workshop supported by ICC and offered by Shelley Smith on the Duluth campus during a mid-winter break in 2008. That workshop provided many ideas that I have used in my own teaching over the past 15 years and that were included in Seven Revolutions/Global Engagement initiatives.

I also participated in a number of Internationalizing Teaching and Learning (ITL) activities over the years; some focused on specific teaching and learning ideas, while others recognized faculty members who excelled in global teaching and learning. I served as a mentor for some ITL programs, and learned a great deal from other mentors and from participants, integrating what I learned into my own teaching and planning for campus internationalization. The ITL workshop format helped inform the structure, content, and activities of the national workshops that were part of the Seven Revolutions/Global Engagement project.

I attended and/or presented at the ICC conferences in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2016. These conferences provided examples of the exemplary internationalization activities that occur across all five UMN campuses. What I learned at these conferences fed into all of my teaching, campus activities, and national involvement. I also had the opportunity to share the work I was doing elsewhere, sometimes being affirmed for that work and, just as importantly, hearing helpful critiques of what I was working on.

A very significant, but sometimes overlooked, outcome of these ICC conferences and workshops is that we get to meet, learn from, and come to like and respect faculty members from all five campuses of the UMN system. These experiences strengthen our personal contacts across the system and promote our identification with UMN. There are too few of these experiences, but ICC offers more than any other initiative in which I have been involved.

The ICC made regular visits to the Duluth campus. Twice a year, usually, an ICC team would visit Duluth and support our international activities. Sometimes we gave presentations on what we were doing at Duluth, and the ICC team shared resources that would enable us to enhance our efforts. Other times we were affirmed by the team for the work we were doing, something that doesn’t happen regularly enough. During these visits, those of us who were meeting with the team had a chance to get together and find out what others on campus were doing. These meetings served to strengthen the ties among Duluth faculty engaged in internationalizing activities.

Conclusion

I was fortunate to select and attend a college that promoted internationalization. In my four years at Macalester College, I went from being globally naïve to having experienced much more of my country and of an important part of the world. I was also motivated to learn more about what was happening internationally.

As a faculty member at UMD, I had opportunities and support to internationalize a series of courses and the campus as a whole. I taught courses on global issues in a number of different contexts and formats for about 40 years. I also had the opportunity to teach in England four times, for a total of over two years. Later, I co-led a planning initiative seeking comprehensive internationalization for our campus. My four years in college were instrumental in helping me to become more globally aware, and I wanted students at UMD to have those same opportunities.

UMD also made it possible for me and one of my colleagues to participate in a national initiative to Educate Globally Competent Citizens, supporting our travel to Washington DC and other parts of the country to work collaboratively with over twenty faculty members to develop model global courses, creative three editions of a toolkit for faculty to meet identified global learning objectives, author an e-book, and conduct workshops for faculty who wanted to enhance their campuses efforts to internationalize the curriculum.

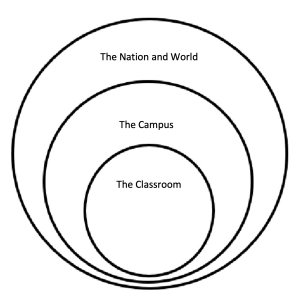

In writing this conclusion, I recognized that I was able to influence internationalization at three levels, which could be graphically represented as follows:

As one person, I had the opportunity to develop courses with global content that impacted thousands of students. My hope is that these students achieved many of the learning outcomes that were identified in the Global Engagement Initiative. I had the chance to co-lead UMD’s Global 2000 plan for comprehensive internationalization at the campus level. The Global Engagement Initiative itself provided me with the opportunity to influence international education at the national level, and some of our efforts spread beyond the borders of the United States.

The University of Minnesota’s Internationalizing the Campus and Curriculum initiative has had a far greater impact on the classroom, the campus, and the nation and the world. Scores of faculty members from across the UMN system, including me, have integrated global content and activities into their classrooms because of ICC workshops, conferences, and support.All five campuses in the UMN system have been internationalized through ICC activities. ICC has served as a model of internationalization across the nation, and UMN faculty and staff have contributed to national and international efforts to integrate global content and activities in higher education.

Coda

I come back to the recognition that Gayle Woodward has been the driving force behind all these ICC initiatives. The ICC workshops, conferences, campus visits, personal support, and other activities would not have been happened without Gayle’s ongoing efforts over the last two decades. I am grateful for all of the opportunities and support that ICC and Gayle have provided. Gayle provides a superb example of the power of one person to impact a system, in this case the University of Minnesota. And perhaps the greatest power a person has is to empower others to engage in positive ways. I am happy to be one of the many people Gayle has empowered.

References

Falk, Dennis R., Susan Moss, and Martin Shapiro (editors). Educating globally competent citizens. A Tool kit for teaching seven revolutions. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2010.