The Undergraduate Research Study Abroad (URSA) program at the University of Minnesota Duluth

Dana Lindaman and Ryan Goei

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

In 2023, roughly 200 students participated in study abroad programs at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD). That’s 200 students out of about 9,500, or roughly 2%. These anemic numbers suggest that study abroad is a hard sell at UMD, whether due to finances, familiarity, fit, you name it. Despite these obstacles, however, the Undergraduate Research Study Abroad (URSA) program at UMD is pulling in close to 40 applicants each year for its 18 spots. These students are applying for a program that requires them to take an additional four-credit preparation class the semester before going abroad, go well outside their Global North comfort bubble for six weeks of independent research, and spend the next academic year analyzing their collected data and writing up the results. Students seem up for the challenge of difficult, intensive academic experiences when the structure supports their participation and success. In fact, it appears that many students desire a transformational experience, a significant challenge, something substantial in a world full of rote tasks and endless distractions.

In May 2023, Angie Lee stepped off an international flight for the first time and walked into the heat of a Moroccan airport terminal. She was there to do research, another first for her, on the rhetoric of water use in a country whose water policies were informed by centuries of dealing with water scarcity. She would meet up with 16 undergraduate classmates, all doing research in their own fields over six weeks. Angie arrived as an average student in the final year of what was, by her own admission, an otherwise unremarkable academic career, but she left with compelling data that she shaped into a paper under the tutelage of her faculty advisor. Angie later submitted that paper to a prestigious national journal in her field, and received a “revise and resubmit.” This success led to a fully funded position in a top-five graduate school in communication. More importantly, she left Morocco with a wisdom and maturity that had previously eluded her. She had faced uncertainty and high academic barriers as an independent adult in an unfamiliar country, and returned home empowered.

In May 2023, Fatima Mohamed arrived back on the African continent she had left at age 11 to emigrate to the US. She was there to explore Jonathan Haidt’s ideas on societal values in the Moroccan context. Within one week, she asked for a private conversation with her URSA leader to help her process the way she was being treated by Moroccans — as a cherished friend and a fully valued human. “They see me,” she confided. “I’m not used to being seen. They think I’m in charge.” As a black Muslim in the US, she was not used to being treated as an equal. In Morocco, she was part of the dark-skinned Muslim majority and felt a deep sense of solidarity and joy. She spent the remainder of her personal time in Morocco exploring her African identity, and used her newfound privilege to advocate for her classmates. She went home after six weeks with enough data to write up her work and submit it for publication. She also came home with a newfound appreciation of her native continent and a deeper understanding of American racism and its impact on her.

These are just two of dozens of stories of transformational growth born of participating in URSA. In this piece we explore several key characteristics of URSA that help explain how we are able to achieve these results and how we attract students to participate in this laborious and time-consuming learning abroad program.

One key reason for these transformational experiences is that we take students out of the Global North. Taking students based in a largely White, Western, Christian community to a largely non-White, non-Western, non-Christian nation has had several important outcomes. First, as Fatima’s story suggests, students of color in Minnesota often experience Morocco differently than do those in the dominant White majority. Consistently, our racially and religiously minoritized students from the US report experiencing a release of the burdens of American racism. That release tends to be emotionally overwhelming for our students of color, as the following quotes — each from different students of color — reflect.

“It felt like I could shed a veil of constant vigilance… I truly felt that the best version of myself… emerged in Morocco.”

“I didn’t know what I was carrying in the US until I wasn’t carrying it anymore in Morocco.”

“Being a Black American, it absolutely had a spiritual effect on my life.”

“In Morocco… I felt as though I was freed from a prison that I was trapped in without me even realizing it.”

At the same time, our White students (who are the majority in Minnesota, but a visible minority in Morocco) experience a sense of being racially and culturally “visible,” often for the first time, leading to powerful insights about their own identity and culture. That experience is equally, if differently, impactful, if different:

“URSA takes students and places them in a non-white, non-Christian, and non-Western environment — thus inviting us to challenge our own assumptions about how we believe the world ought to be. My time in Morocco taught me so much about approaching the world with humility, allowing people to reveal themselves to me, and appreciating the differences that make us unique.”

“…getting to immerse myself in Moroccan culture, learning to communicate with people who didn’t speak my same language, and learning a completely new way to live was truly eye opening. You will be pushed, challenged, and exhausted, but I mean all of those things in the most wonderful way possible!”

“In short, my study abroad experience in Morocco was life-changing… Going from a westernized way of living to the way of living in Rabat, Morocco, was something I’ve never experienced before”

“I learned more about American racism by living in Morocco than I have by living in the US.”

Our white American students tend to say things like “Morocco will challenge you,” while our students of color often say things like “Morocco felt oddly familiar in the best way possible.” These divergent experiences are important and form the basis for impactful, if unique, learning experiences for students from both groups. URSA students report engaging in deep conversations about race and racism both in Morocco and in the US, based on witnessing each other walk these unique, racialized experiences. Some really important lessons on culture, race, oppression, and privilege occur through communication among URSA students based on these discrepant experiences — experiences birthed by altering which groups are minoritized or marginalized.

These learning experiences are important, but taking students outside the Global North has other benefits as well. Traveling to a non-Western, non-White, non-Christian country may support recruitment of students from minoritized groups in the US, groups that tend to be underrepresented in study abroad. Our students of color report several reasons for participating in URSA, but location is one. In addition, traveling outside the Global North provides our students with the culturally disorienting experiences that research shows lead to empowering, often transformational, learning experiences (Gibson, et al., 2023).

These rich learning experiences happen because we take seriously the call by Brewer and others to create education abroad experiences that “not only contribute to student learning and development but also serve as a catalyst to help students find connections across undergraduate education and advance their learning and development toward lifelong learning.” (Brewer, 2019) If students are expected to benefit from study abroad as a high-impact practice, then it needs to be embedded in their undergraduate education as an integral part of their experience rather than as a commodity to be consumed. For us, that means forging stronger connections between students and faculty, as well as between study abroad and their disciplinary coursework. The most meaningful study abroad experiences, in terms of student learning outcomes and personal development, are substantial, baked into the curriculum, and led by faculty who know their students. In our case, we built a program that requires a nearly two-year commitment from students. That commitment starts with the selection process.

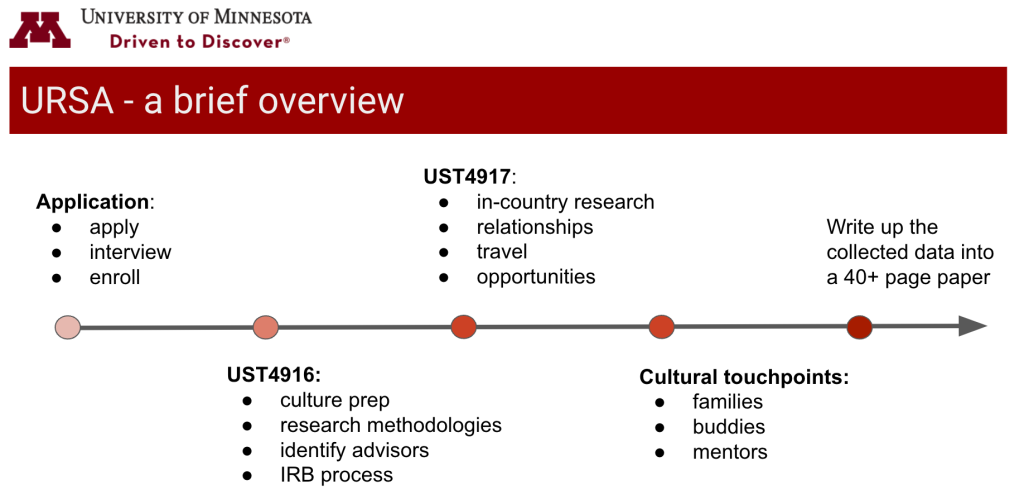

The URSA Process

The first step of URSA is the application. Students apply to the URSA program in the fall semester of the year before the trip, submitting a writing sample, transcript, and letter of intent. We read through these applications and choose a pool of finalists to interview in person, then use these materials and the interviews to make offers to 18 students. We are not looking for the 18 students with the best grades or the most research experience. We are looking for the right combination of students who can each make a meaningful contribution from their classroom, research, travel, and life experiences to a coherent overall group experience. The students who are accepted and commit to the program then register for the URSA spring preparation course.

Step 2 is a 4-credit spring course, along with numerous individual meetings with the URSA program leader and a discipline-specific faculty advisor. In the course, students are introduced to Moroccan history, local customs, basic language greetings, food options, transportation types, and various other cultural elements of importance to them. We invite Moroccan guests to the class so students can ask questions about life and research in Morocco. Because Morocco is a strongly relational culture, we help students make these connections early to facilitate the conduct of their research later. During the class, we ask students to read and discuss how differing value lenses contribute to cultural misunderstandings and have them work through the most common ones to identify the issues. These insights help prepare them for the unavoidable obstacles (cultural and otherwise) they will encounter while in Morocco, and set them on the path toward looking for beauty in places and ways they may not be accustomed to.

One key lesson of the spring preparation course is to prime students to approach their study abroad experience with humility. A focus on humility helps facilitate the quest to find beauty in the unfamiliar, works against commonly held beliefs that nations like Morocco are behind the US and could/should learn from us, and thus facilitates more effective, engaged research, deeper learning, and more meaningful cross-cultural relationship building. There is a paradox of intercultural experiences, particularly when those experiences occur between culturally distant groups (like the US and Morocco). Sometimes intercultural experiences lead students to perceive greater divisions between cultures and lead students to have less desire for diverse interactions. The spring preparation class is key to helping students work against that paradox.

During the spring semester, the URSA leader helps each student identify a research topic and a faculty advisor in their field. The URSA leader also connects each student to a Moroccan student peer and a Moroccan cultural liaison (often a faculty member in their field). All research must be submitted through the IRB office at the University of Minnesota (UMN) so that students learn the importance of respecting human subjects in any research and so that they are fully prepared to submit their research for review at conferences or publication outlets. The semester ends with a banquet for students and families in which we invite URSA alumni to welcome the new cohort into the URSA family and inspire them with stories from their learning experiences abroad.

Students arrive in Morocco around the second week of May, beginning the third step and the highlight of the program. For some, this is their first time out of the US. They spend the first five days in orientation, shuttled around Rabat (their homebase while in Morocco) and to another city for a taste of life outside the capital. During these first few days, we make sure all students have a working phone with a Moroccan number, a bank card that can draw cash, and an understanding of the public taxi system. Students also meet their Moroccan peer buddy and their faculty liaison. This five-day orientation is critical for the URSA peer bonding that began during the spring class. The shared experience of the unfamiliar binds students closer.

After these five days, students are placed in pairs in family homestays in Rabat and allowed to autonomously pursue their research questions/data collection for the remaining five weeks. The URSA program leader responds to issues as they arise — normally around adapting research to conditions in the field, access to organizations, interpretation of collected data, or personal issues. Equally important is the time spent supporting each student’s individual cultural experience in Morocco. We structure this individual support into weekly meetings with each student over the five weeks. With a faculty focused on knowing their students, the bond of trust built up over the application interview, the individual research support meetings, the spring semester preparation course, and during orientation in Morocco provide the foundation for a meaningful faculty-student relationship. The students are independent, but they check in regularly with questions or ideas via text, phone calls, or spontaneous meet-ups. Students also find it easy to support one another since no host family is more than a short walk or taxi ride from another.

After the six weeks in Morocco conducting their project, students return to the US and, with the guidance of their URSA leader and their expert faculty advisor, complete their URSA project by writing up a thesis-level edit, getting comments from expert readers, publishing in the University database, and printing and binding their project. Students have the entire next academic year to complete the project. URSA students also sit for a face-to-face debrief with their program leader and reflect on their experiences in writing. In two years, the program has produced multiple Fulbright applications, several fully funded law and graduate school positions in the US and Europe, curious job interviewers, peer-reviewed publications, and numerous conference papers and articles. It has become one of the most fruitful sources of student creative output on our campus. URSA is a rigorous academic program whose scholarly output is matched only by the transformative personal experience of its students. How is it that a program so demanding is so attractive to students?

URSA and the Five Barriers to Study Abroad

In 2005, due in part to the low participation rate in study abroad, UMN conducted a comprehensive needs analysis to better understand the barriers that prevented students from studying abroad, summarizing their findings into the five Fs: financing, fit, friends/family, faculty, and fear. While many study abroad faculty and administrators attempt to address these barriers, URSA does so through a unique approach, which may help readers understand how we have been successful in attracting students to undertake such an in-depth study abroad program.

Financing, or cost, is a factor for most students considering study abroad. Many programs are prohibitively expensive, especially for students on scholarships or with significant loans. URSA minimizes costs to students in a few interwoven ways. First, there are no classes in Morocco to pay for; the costs in Morocco are related to each student’s research, which is much less expensive. Second, there are no third-party study abroad vendors to pay for. Students are responsible only for their own traveling and living costs, the UMD study abroad fee, the URSA leader salary, and the on-site research support from our Moroccan partner university (the International University of Rabat). The relatively low cost of living in Morocco compared to Minnesota also helps make finances less of a concern for URSA students.

Our time together in the spring class allows us to support students in a search for study abroad scholarships and research support dollars throughout the university system. In part because they are taking on such a monumental academic challenge, URSA students regularly procure funding from research and study abroad financial support structures. We also approach the financial barrier by emphasizing the ways in which their work in URSA will advance students to graduation. Students are much less concerned about costs when the study abroad experience fits in their program of study or otherwise facilitates their graduation progress.

URSA approaches the second barrier, fit, in a variety of ways. First, students get to choose the field in which to conduct their research. As such, the 10 credits (4 in the spring preparation course and 6 in the summer abroad course) can often be applied to the student’s major or minor. Even so, students often find it hard to fit study abroad into their busy schedules and lives. Students from programs with strict accreditation standards, blocked schedules, and heavy credit loads have a difficult time participating in study abroad without extending their academics into a fifth year. Nearly half of our URSA students come from these highly regimented programs because we intentionally integrate their learning and development abroad into their academic programming on campus. In other words, the student experience in Morocco is designed as an outgrowth of their overall educational experience that connects directly back to their undergraduate curriculum at UMD.

We sought out similar requirements on campus and designed URSA to fulfill those requirements as well, giving students the opportunity to fulfill multiple requirements by completing URSA. For example, we worked with the Writing Studies Department to ensure that URSA requirements would fulfill the university’s Advanced Writing requirement, and made sure that URSA meets the Global Perspectives requirement in the university’s Liberal Education program. And UMD’s University Honors program mandates that students complete honors courses and engage in independent research, so we structured the URSA spring preparation course to fulfill a University Honors course requirement and the URSA project to fulfill the University Honors independent research expectations. Students in the University Honors Program can thus participate in URSA and simultaneously make progress on their advanced writing, liberal education, major, and several University Honors requirements. These opportunities to fulfill multiple requirements make URSA more attractive to more students.

Day-to-day class schedules pose another challenge, and we have structured URSA so that busy students can make it fit without changing their existing class schedule. We offer the spring preparation class over four long Saturdays and during one-on-one meetings with students, and the six weeks abroad in the summer happen outside the usual fall/spring semester schedule. As such, the program can fit neatly into the busy schedule of almost any student. One of UMN’s primary internationalization goals is to increase study abroad participation both in terms of overall student numbers and also through expanded opportunities for students commonly underrepresented (e.g., men, students of color, and STEM, business, and other high-demand majors). URSA creates a pathway for almost any student, from any discipline, to participate.

The excitement of family and friends as they dream with the student about their opportunity to do research in Morocco often gives way to misgivings about the potential dangers of a country many Americans know little about. Parents may become particularly concerned about the safety risks posed to their child while abroad and about the academic risks of doing serious research, and prevent students from participating in URSA. We attempt to mitigate these fears by connecting students and parents to the URSA leader and to alumni who can provide first-person accounts of their own experience. Parents and other family members are invited to the spring banquet, where they hear URSA leaders articulate the goals of the program and listen to alumni speak to their own transformative experiences. Nothing reassures parents or inspires URSA students more than the poise and composure of our alumni. At the banquet in 2023, one parent told us that they had some concerns about their daughter going to Morocco, until that night. When we saw that parent again in 2024 at the research showcase, she said that URSA was the best money she had ever spent on her daughter. That student later came to the first recruitment fair for 2025 and spoke to the interested students about her own growth from a shy and anxious young woman to a comfortable and confident introvert. She held that room in her hand. When she was done speaking, every student looked at us as if to say, “I’ll have what she’s having.”

Faculty support of students is central to the URSA experience. At UMD, the URSA program leader and the faculty advisor both play key, intensive roles in supporting students. The program leader takes on the most substantial role, with a lengthy set of responsibilities across two years or more. They must plan the program with Moroccan partners, convincingly present the perks of URSA while recruiting, reviewing, and interviewing applicants, guide students through the formation of their research ideas, connect them to faculty experts in their field, prepare students for a very unique cultural experience, and then attend to their individual, cultural, and research needs while in Morocco and ensure they complete their projects upon return to the states. Likewise, the faculty advisor provides significant support by providing expertise in the specific area of study. Along with the URSA leader, they help shepherd students through the project. The URSA leader sometimes serves as the expert faculty advisor as well, if a student is doing a project in their area.

We believe the faculty-student relationships are key and that each student requires individualized attention to optimize both their research and any potential transformational learning that comes from the experience. When faculty know their students, and students their faculty, a bond of trust forms that allows faculty to understand student needs and students to more clearly speak those needs. This bond forms the basis for success in both preparing and completing the URSA project and learning important intercultural lessons. The URSA structure allows the URSA program leader to connect individually with each student right away during the application interview process, and to continue doing so during the spring, with the preparation course and individual meetings. These connections are further strengthened in-country during orientation and the weekly individual meetings. The URSA leader’s role in tailoring experiences and support for each student is central to achieving such compelling research and learning outcomes.

Fear is one of the most common obstacles to study abroad. Students often face fear of the unknown, fear of cultural differences, fear of autonomy, fear of academic challenges, and fear of separation from their family and friends. One common response to these fears is to remove them preemptively to increase comfort and interest in the program. The fear barrier, however, is unlike the other four barriers. Removing the things that frighten our students further facilitates a trend toward predictable programming that keeps our students busy in a familiar, highly structured bubble, going to destinations within the Global North that are largely Western, White, and Christian. Highlighting the familiar and removing perceived risks may make some sense for some students, but the sum of these efforts has the unfortunate side effect of stultifying the culturally disorienting experiences that can lead to transformational learning and empowerment (Gibson, et al., 2023). Central to the URSA program is preparing students to embrace the difficult, the unfamiliar, and the unpredictable. When introducing URSA, we tell students that the program will not be easy, that there will be many expected and unexpected difficulties, that they will feel discomfort and fear, and that facing those fears is exactly what will make it so rewarding. Perhaps surprisingly, this appears to be one of the reasons students choose URSA.

To be clear, we are not opposed to reducing actual risks in study abroad environments. Instead, we focus on perceived risks that are born of inexperience or stereotypes, which can be remedied by embracing the fear and learning through experience. Walking through the unfamiliar until it feels safe, and facing the impossible so that it becomes possible, is an empowering and transformative experience that humans need. There are several good reasons to teach our students to embrace things they fear (e.g., independent research or culturally disorienting experiences in very different places). Research suggests that students often struggle with their mental health and their academics because they are not given enough space to face fears, fail, and work through those fears (Haidt, 2019). Students are empowered when they accomplish something difficult. And students who complete difficult tasks set themselves apart in tight graduate school and job markets. Their resumes look different and they carry themselves differently in interviews because their understanding of the world and self has fundamentally changed.

Initial Reflections and Conclusion

We built URSA to offer students the chance to do something big — to take on an extensive challenge, face several fears, embrace a stark cultural experience, and set themselves apart from other undergraduates. The risk of raising the bar so high is that fear would stifle their interest in participating. To work against that, we did not try to reduce the fear by preemptively removing it. Instead, we attempted to allay the other most common barriers to participation and double down on the gains students will realize by embracing those fears. Initial indications are positive on this front. In its two years to date, URSA attracted 36 applicants. At this rate, the program could probably be expanded to offer more students the opportunity to participate. Given the low rates of participation in study abroad overall, this is a particularly surprising and important trend.

We designed URSA to make it accessible to any motivated student, no matter their situation. We have found some initial successes in making study abroad more accessible. We have only taken two cohorts (in 2022 and 2023) to Morocco, so these numbers offer only an initial glimpse. In our first two cohorts, we had nearly triple the proportion of students of color participating in study abroad, with students of color making up 24% of URSA students compared to only 9% of all UMD study abroad students. Men, another underrepresented group in study abroad, make up 34% of URSA students but only 30% of all UMD study abroad students. UMD has four colleges: The College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, the College of Education and Human Service Professions, the College of Business, and the College of Science and Engineering. In the past two years, we sent fewer students abroad from the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences (28%) than UMD international programs overall (45%), and fewer from the business college (6% v. 11%). At the same time, URSA comprises about the same percentage of students from the College of Science and Engineering (31% v. 29%) and more than doubles the proportion of students from the College of Education and Human Service Professions (34% v. 14%).

It is often the case in study abroad offices that, to increase student interest, faculty and staff attempt to remove all barriers to participation, including those related to academic work or perceived barriers based on a lack of cultural experience outside of the Global North. Our experience with URSA suggests that one can selectively reduce some barriers to study abroad (finances, fit, family/friends, faculty) while maintaining, even increasing, those perceived barriers related to academic difficulty and cultural uncertainty, and still attract students. We have found that many students crave this type of experience even if they fear it, or perhaps because they fear it. The URSA model offers students and universities the opportunity to increase their academic profile while not sacrificing, and while perhaps even increasing, student participation in study abroad experiences.

References

Anderson, L.C. (2005). Overview of the curriculum integration initiative. In L.C. Anderson (Ed.), Internationalizing undergraduate education: Integrating study abroad into the curriculum (pp 8-11). University of Minnesota. https://umabroad.umn.edu/sites/umabroad.umn.edu/files/documents/Internationalizing%20Undergraduate%20Education-%20Integrating%20Study%20Abroad%20into%20the%20Curriculum.pdf

Gibson, A., Spira-Cohen, E., Sherman, W., & Namaste, N. (2023). Guided disorientation for transformative study abroad: Impacts on intercultural learning. Studies in Higher Education, 48, 1258-1272.

Iskhakova, M., Bradley, A., & Ott, D.L. (2023). Meaningful short-term study abroad experiences: The role of destination in international education. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 23, 400-424.

Minnesota and Morocco find common ground in wheat (2018). University of Minnesota Extension (retrieved May 19, 2024) from https://extension.umn.edu/source-magazine/minnesota-and-morocco-find-common-ground-wheat

Vande Berg, M., Balkcum, A., Scheid, M., & Whalen, B. (2004). The Georgetown Consortium project: Interventions for student learning abroad. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 18, 1-75.

-

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

↵