“A New Path for Multilingual Publication: Challenging the Status Quo by Asking ‘What if…’”

Stephanie Gingerich

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

“Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” —Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail

There she sat. Beneath the weight of her experience, her leather rocking chair swayed her back and forth as she shared stories of her past. Every word, every rolled “r” in her speech, flowed over me like a song, filling me with knowledge from generations before me. Mi abuelita. My dear grandmother. With her salt-and-pepper straight hair, her olive-toned skin, and the gentle wrinkles on her face, she told me about her childhood, my ancestors, and the land and water, and sang songs from our past. She taught me about parenthood, plants, saving money, and the importance of education. She always spoke of how important it is to know one’s culture and understand who you are and where you come from. Full of love, grit, and wisdom, she taught me so much over the years, and continues to shape me into the person I become each day. As a child, I learned about sugarcane and growing chickens. As an adult, I have come to admire her ability to succeed and thrive. Her stories of the past and her push for me to continue to grow and learn are lessons I carry with me every single day.

Mi abuelita instilled the values of education for me very early on. As an adult, I push those learnings to international knowledge and recognize the importance of knowledge exchange as we progress into a world where global and local events are interconnected. We must be attuned not only to the information generated within our own communities, but to the knowledge garnered globally. We need to continue to listen to generational knowledge and new research emerging from people and cultures around the world. This global exchange of information is dependent on our ability to exchange knowledge in languages in which people can receive it, and on the resources to disseminate that knowledge.

As a multicultural and bilingual Hispanic woman raised by a Panamanian mother in a military family, living in countries around the world, I learned to embrace the viewpoints and experiences of other cultures. My mother, as well as mi abuelita, instilled the values of education and curiosity early in life. This inclusive upbringing empowered my curiosity and excitement about the cultures, languages, food, experiences, and lives of others everywhere, and has contradicted some of the experiences I have had over the years. In one such example, I was dismayed at how easily my professors taught ethnocentrism in a college course. The professor recommended that I and my 75 classmates use the filter feature in a literature review to exclude articles in any languages other than English, and to only include articles written by or about organizations within the United States. The professor’s rationale? Articles written in other languages or about other parts of the world were not relevant to our work in the US. In an assignment to conduct a literature review of peer-reviewed articles, they perpetuated the belief that only one story has value — the story contained in articles written in English.

While I may have sat stunned and unsure what to say in that moment in my early 20s, I have found my voice throughout my career. Rather than idly sitting by during instances like these, I have become a part of the solution to ensure that more voices are heard around the world. Mi abuelita instilled the values of education and, as part of my career, I help others to share their knowledge for all to access worldwide. For this I am grateful to not only those who supported me but also to the position I’ve been afforded in order to ensure that people’s stories can be heard. We have much to learn from each other. Why limit ourselves to what is right in front of us? Rather, we should search far and wide. Push beyond the boundaries of our own comfort zones to learn from others like and unlike us, from cultures of distant lands. Be curious and inviting. We can become more attuned to knowledge sharing and can be the ones who lift up the stories of those who would otherwise be consistently filtered out.

In that spirit, this article offers the story of one attempt to utilize partnership principles, leveraging the institutional resources of the University of Minnesota (UMN), the “power of one,” (one idea, really), and a small circle of scholars committed to making international work available across borders through The Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies to publish an article written in Spanish as a multi-lingual publication. It discusses the foundation for this work, challenging assumptions of language dominance in the scholarship world, the application of translational methods with attention to available resources, and the development of a multilingual publication model, the Model for Partnership-Based Multilingual Publication (MPBMP), to guide others in pursuing similar endeavors in the future. With a team of dedicated scholars and partnership principles in place, a multilingual publication was realized and a new idea for inclusive publication emerged within this journal.

Partnership Principles in Sharing Academic Research

The Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies (IJPS) is an international, scholarly, open-access, peer-reviewed journal supported jointly by the Center for Partnership Systems, the UMN School of Nursing, and the UMN Libraries. The goal of IJPS is to “share scholarship and create connections for cultural transformation to build a world in which all relationships, institutions, policies and organizations are based on principles of partnership” (IJPS, n.d.). Using the principles of partnership contained in social scientist Riane Eisler’s Cultural Transformation Theory (Eisler, 2018a, p. 10-11), the journal publishes articles about work being done around the world, with an emphasis on partnership approaches. To provide a more inclusive, equitable, and accessible approach to knowledge dissemination for authors around the world, articles are published at no cost to the authors.

According to Eisler’s Cultural Transformation Theory, societies orient on a continuum between partnership and domination in their family and childhood relations, gender relations, economics, narratives, and language (Eisler, 2018b). The core characteristics of domination systems are:

- Authoritarian rule in the family and the state, with strict hierarchies of domination;

- Male dominance and devaluation of “feminine” aspects such as caring and nonviolence;

- A high degree of socially approved abuse and violence; and

- Language and stories that present domination, as well as the violence needed to impose or maintain it, as normal, moral, and inevitable. (Eisler, 2018a)

At the other end of the societal spectrum are partnership systems, characterized by:

- Egalitarian structures in the family and state, with hierarchies of actualization that empower rather than disempower;

- Equal partnership between genders, with inclusive, equitable empowerment of all;

- A low degree of abuse and violence, as it is not needed to impose or maintain rankings; and

- Language and stories with respect, accountability, and benefit as natural, not normalizing or idealizing abuse and violence. (Eisler, 2018a)

IJPS articles capture the essence of partnership approaches around the world and highlight how these approaches can be actualized in various disciplines and settings. These were the partnership principles the team worked to honor in translating and publishing this article in two languages.

Amplifying the Voices of Scholars from Cuba

Since 2017, faculty from the UMN School of Nursing have led trips to Cuba, in partnership with Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC), for week-long immersions to gain deeper understanding of the country’s national prevention-based health-care model. MEDICC works with people and organizations in the US to promote and facilitate US-Cuban health collaborations in an effort to share the “quest for health equity and universal health worldwide” (MEDICC, n.d.). During these immersions, faculty members, including myself, formed scholarly relationships with Cuban researchers who had led a decade’s worth of investigations into the impact of the family environment, school, and media on the gender perspectives of young children. The research was received with great enthusiasm by the UMN faculty and students, who proposed that the researchers submit a manuscript to IJPS to disseminate the knowledge in a novel way in order to uplift the voices of scholars from Cuba, a country often disregarded by the rest of the world.

Challenging the Dominance of English as the Default Language

With clear alignment to the principles of partnership, the question became not whether to publish the article, but how best to do so. The manuscript submitted by the Cuban authors was in Spanish. At this point in the journal’s history, all articles were published in English. Originally, the proposal by the editorial board was to translate the Spanish manuscript into English for publication. As an editorial board member who is bilingual in both Spanish and English, I proposed using my skills to offer a new model of publication within this journal.

“What if… we publish the article in both English and Spanish?”

Doing this would challenge the narrative that English must be the dominant scholarly language, and would allow the research to reach a much larger audience. As the only board member who spoke both English and Spanish, I was delighted to lead this project and uplift the foundational principles of partnership throughout this work.

Small journals often have few resources to achieve this type of goal. Much of the work of producing IJPS is done by members of the editorial board, who are all volunteers; there are no funds for review, editing, or compositing. Despite the limited resources, there were several things in our favor. The journal is supported by the UMN Libraries, including an experienced librarian and an online platform with room for the article in both languages. Our most important resource was a team committed to equity in scholarly dissemination. The editorial board members saw the value of publishing the article in the native language of its authors, and of providing a venue for Cubans to share their research internationally.

Because publishing this multilingual research article in IJPS had to be cost-neutral, volunteers were sought to support the translation process, with dominant speakers in both English and Spanish as well as Spanish-speaking peer-reviewers, to ensure that the integrity of the message was retained. The article needed to be translated into English, but both versions had to be peer-reviewed and copyedited in their respective languages, with the final versions reconciled to ensure that the same message existed in both. The team that formed to work on this “What if?” comprised the Cuban article’s first author, myself as the bilingual translator, content expert peer-reviewers in both Spanish and English, two copyeditors, and the IJPS editorial board.

Addressing Biases and Stereotypes

It would be naïve to believe that any individual or team is not influenced by their belief systems, including biases and stereotypes. If left unchecked, these beliefs could interfere with the translation, peer-review, or copyediting processes that our team was pursuing with this work. Both as individuals and as a team, we thus needed to address our unique belief systems.

Biases are the personal preferences that people hold towards a particular topic that limit the individual’s ability to be objective (Bourke, 2020; Country Navigator, 2023), while stereotypes are preconceived ideas or generalizations applied to large groups of individuals, typically holding a negative connotation (Bourke, 2020; Country Navigator, 2023). These may have developed from stories within our cultures passed down through generations; they may result from lack of knowledge and understanding; or they could even be a result of disregard for other individuals or groups of people. Whatever their basis, we must all acknowledge that they exist within our belief systems and that we are not immune to their presence. Rather, as a team, we needed to understand the stories and beliefs that have shaped the biases and stereotypes within our mental models, and then, most importantly, decide how to address them.

Additionally, as a team, we felt it necessary that we should be able to have open dialogue and discourse about these sensitive topics. In discourse, people engage in verbal and/or nonverbal communication to exchange thoughts and ideas (Blommaert, 2005; Johnstone & Andrus, 2024). The team effectively applied the principles of partnership in order to address biases and stereotypes through discourse. The following sections describe these concepts in more detail and explain how we applied them to the Cuban article.

Self-Work

We are all shaped by our past, our stories, generational and current. The stories passed down to me by my mother and mi abuelita shaped my beliefs about the world. Negative and positive experiences guide the way we think and influence our behaviors. Therefore, in order to identify our unique biases and stereotypes, we should challenge our ways of thinking by asking ourselves such questions as:

- What beliefs do I have about others?

- Where do these beliefs come from?

- What is perpetuating these beliefs?

- Which beliefs should be challenged?

- What can I do to understand the impact of the beliefs I continue to hold?

- What should I do right now to address the impact that my beliefs have on others?

Given these types of questions, the individuals on the team identified their unique belief systems which might influence the translational process. One such example was the political understanding of the historical relationships between the US and Cuba, which needed to be considered to ensure that beliefs about either country did not influence the work. We also needed to check our understanding vs. our assumptions of the culture and language within Cuba.

This is work that each of us should do in our professional and personal lives, especially in work that crosses languages, cultures, and countries, as one step in challenging our own understandings and belief systems about the world. Rather than limit the world to the belief structures we have defined or that have been defined for us, we can open our minds to new learnings and new beliefs, thus challenging our old models of thinking.

Team Work

Similar to the self-work addressing our individual biases and stereotypes, a team should also engage in this process. Together, its members should acknowledge biases and stereotypes that exist within the culture of the team, unit, organization, or other work group, and that may significantly influence its members’ ability to work together and to be innovative throughout the project. This discussion needs to start at the beginning of the project and continue throughout, with such questions as:

- What beliefs exist within the team about others involved in the work?

- Where do these beliefs come from?

- Are these beliefs unique to the team or are they also present within the larger department or organization?

- What beliefs should be challenged?

- What needs to be done to enable the team to be open to changing their beliefs?

- How should individuals speak up about beliefs that should be challenged and/or supported?

Ultimately, it is important that a team and each individual member acknowledges the belief systems we all hold. While we all have biases and stereotypes, what matters most is what we do with them. Do we hold onto these beliefs? And if so, do we understand what the impact may be? Or,do we challenge them, allowing space for new knowledge and new beliefs?

Discourse

Within the translational process, our team engaged in discourse while incorporating the principles of partnership to include not only the exchange of ideas but also a culture in which individuals felt comfortable sharing their opinions and challenging those of others. This hierarchy of actualization allowed people to address concerns that might be barriers to reaching the common goal. Engaging in dialogue helped us to see where bias and stereotypes affected not only our individual approaches, but the collective team approach as well.

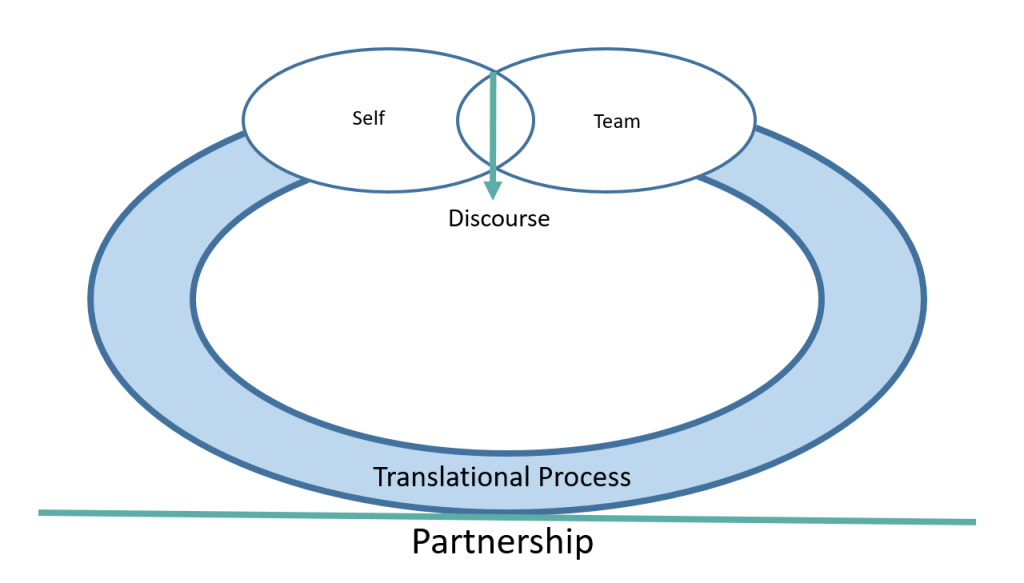

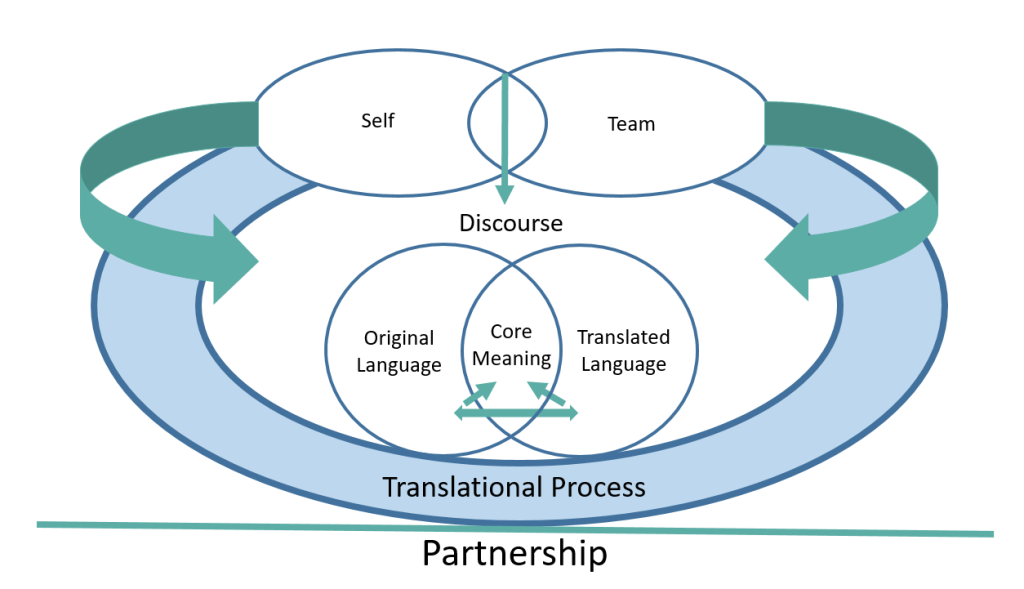

Figure 1 shows the work of individuals and the team to address biases and stereotypes while being open to discourse, as the foundational culture of the work is based in partnership principles.

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the work of challenging the self should begin before and continue throughout the process of translation. It is important to understand what biases and stereotypes we carry and to discern even more closely how they may be affecting the work itself. We must come with an openness that our belief system can shift from old learnings to new ones, and be open to those learnings throughout the engagement with the team. In engaging in this self-work, we each were able to ensure that our influence was removed from the translation process to ensure that the integrity of the piece was maintained. This also applies to the biases and stereotypes that exist within a team. All the while, this work should occur in discourse based in partnership to ensure a culture where all can speak up to address any issues which may be a barrier to the work.

In the case of the Cuban article, the editors and reviewers needed to address their unique beliefs and behaviors while also being mindful of the beliefs and behaviors of those within the team to challenge in a productive manner any actions which were harmful or created unnecessary barriers to publishing the article in both English and Spanish. During the work of translating this piece, the team engaged in multiple respectful conversations to address inconsistencies, assumptions, misinterpretations, and incorrect changes, and even challenged changes that may be appropriate in one culture but not another.

Synthesis of Translational Methods

One major barrier to publishing this article was translation — specifically, the model or process we were going to use to successfully complete an accurate translation. Language translation is not as simple as converting a document word-for-word into another language. There are nuances that include context, cultural understandings, dialects, and linguistic structures. All of these factors can impede the translator’s ability to transform a message from its original language into a different language while retaining its integrity, and must be considered when navigating the nuances of language differences and conveying messages globally.

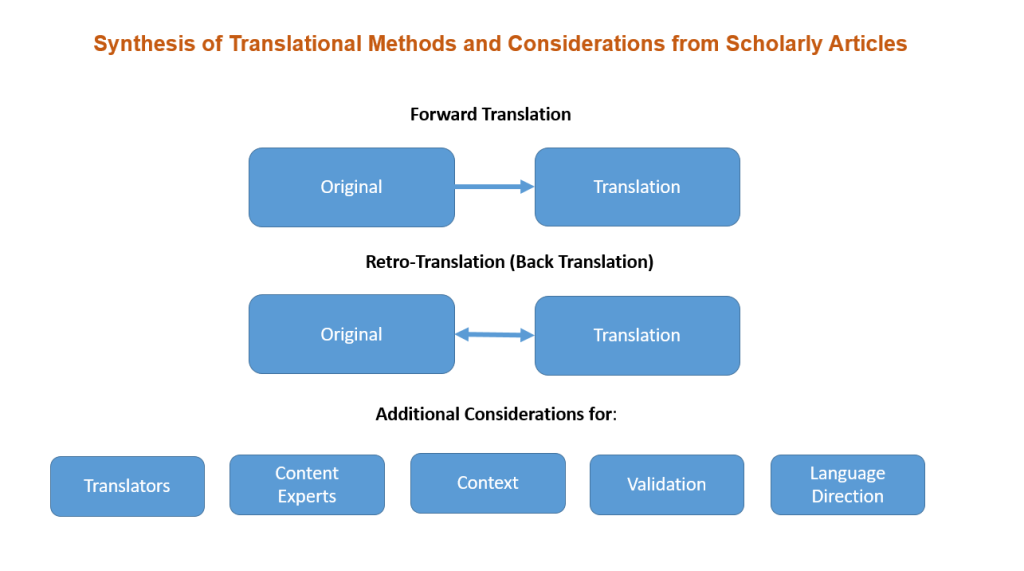

According to Volkova (2014), an important component of translation is defining the strategies to be used to support the team during the translation process. This work should begin before the translation itself. Additional research includes recommendations about the translational processes for translating a document from one language into another. Scholars identify various methods and considerations for these practices, as summarized in Figure 2.

(Ares et al., 2012; Beaton et al., 2000; Brislin, 1970; Epstein et al., 2015; Guillemin et al., 1993; Hendricson et al., 1989; Maneesriwongul & Dixon, 2004; Wild et al., 2005)

Some methods focus on Forward Translation, a one-directional process in which a message is translated into a second language while retaining the original document intact (Ares et al., 2013; Beaton, et al., 2000; Guillemin et al., 1993; Maneesriwongul & Dixon, 2004; Tsang et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2005; ). Other methods include a process by which the document is translated into a second language by one expert, and a different expert then translates the document back into the original language. This process, known as Retro-Translation or Back Translation, is used to ensure that the translated message holds the same meaning as the original version, correcting variations that may occur during the translational process (Guillemin et al., 1993).

In both processes, the translator must consider the language in which they are most proficient, determining in which direction the translation is most appropriate — the original language or the target language, as indicated by the term “language direction” in Figure 2. To address cultural nuances within the target language, it is recommended that translators work to translate into their dominant language (Hendricson et al., 1989; Wild et al., 2005); some also recommend that the translator or another member of the team should reside in the target country to address these cultural and local nuances (Wild et al., 2005).

Additional recommendations include convening a team of content experts, language scholars, and individuals unfamiliar with the content to address discrepancies between the original version and the target language version, to ensure that the translation contains the intended message and does not inadvertently misrepresent or misinterpret the information (Ares, 2013; Beaton et al., 2000; Guillemin et al., 1993).

Among the various methods for translation, one must consider the intended purpose of the translation in order to identify the best method to use. Additional considerations include the language expertise of the translators, the qualifications of the content experts, context, measures of validation, and who is officially responsible for the result.

Applying Translation Methods

To reach our goal of a multi-lingual publication, our team needed to identify available resources to complete the work, the key partners needed, logistics for publication in the online journal, the method by which the translational process would occur, and ways to address biases and stereotypes. As a team, we defined the scope of the project and the strategies with which to complete the work, incorporating partnership principles of egalitarian structures, hierarchies of actualization, and respect (Eisler, 2018a) as a foundation for the culture and for the project as a whole. With limited resources, we used a hybrid of Forward Translation and Retro-Translation, while also assessing the biases and stereotypes we identified as barriers to the translational process.

Retaining the Core Message of the Article

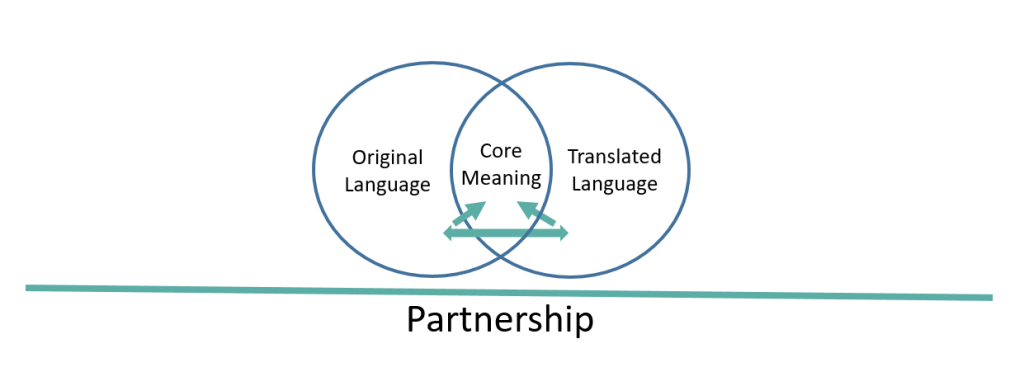

As discussed, in order to move forward in unison, the team must identify the intent of the multilingual publication. In the case of our article, the intent was to disseminate the scholarship broadly in two languages while retaining the core messaging in both. Directly translating into a second language could lose some of the message and cultural context. Specific considerations for such a project may include gendered words, the direction of the text (left to right or right to left, horizontal or vertical), and whether words exist in the target language or need to be described. These considerations may result in changes to the original document, generated by peer review and copyediting. Peer review ensures that the content of the article is accurate, complete, clear, and in accord with the journal’s specifications. Copyediting ensures that the reader has the best opportunity to understand the messages. In the translational process, the results of peer review and copyediting may require changes to both versions, so that the core meaning aligns in both languages. There are many hands in this work, including the authors, translators, and peer reviewers and copyeditors in both languages. The foundation of partnership principles ensures respectful dialogue as messages are questioned and translations are evaluated across cultures. See Figure 3.

During the multilingual publication process, our team had a clear understanding of the core message from the original language. While ensuring that this message was retained, both the Spanish and English versions were peer reviewed and copyedited to hold a similar and culturally appropriate message with the core meaning intact, all while ensuring that partnership principles were the foundation for the communication and relationships throughout the work.

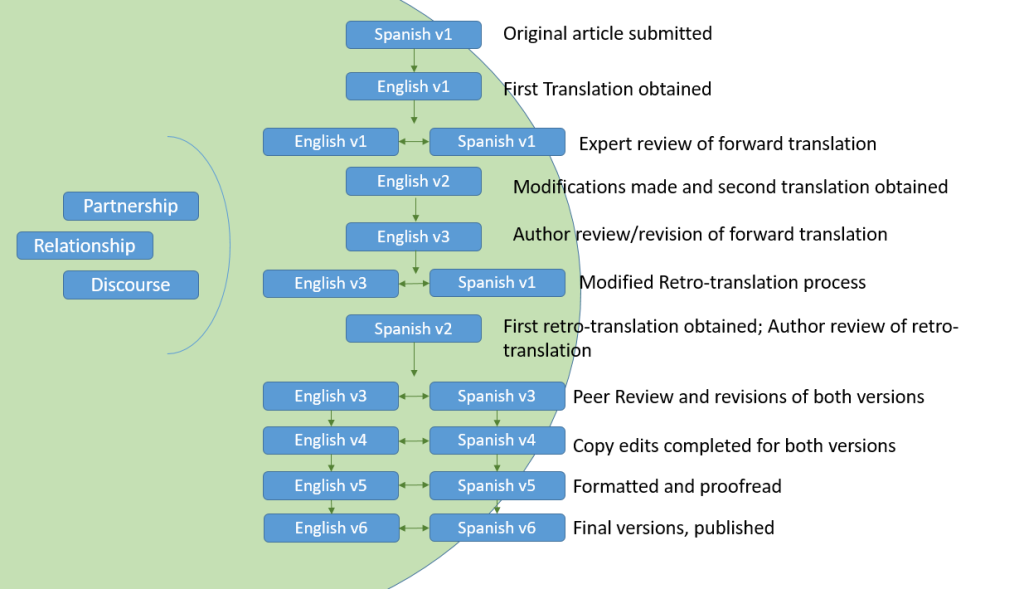

Resources, Logistics, and Possibilities Drive a Process

As the team addressed the “What if…” and embarked on the possibilities of a multilingual publication, we discussed resources, logistics, and possibilities. Resources needed in order to publish the multilingual article included time; content experts who were fluent Spanish and English languages and culture, respectively; bilingual individuals who could translate in both directions or in at least one direction; and the capacity to confirm messaging with the authors in both languages. Logistical considerations included needing twice as much space as our other articles in order to publish complete versions in both languages. Using a modified version of the Retro-Translation process, the team began with the original article in Spanish. Figure 4 shows the process that led to successful publication of the article in both languages.

Based in partnership, relationships with one another, and discourse throughout the work (noted on the left), our multilingual publication work occurred as indicated from the first version (Spanish v1) through to the final versions (English v5 and Spanish v5). These methodical and tedious steps were intentional to ensure attention to detail, language, culture, and all the considerations for the publication process.

The process began with the original article submission (Spanish v1) by the authors. As the bilingual translator, I translated the content of the original version into English (English v1). The English and Spanish scholars and the first author then reviewed the translation, yielding a revised English version (English v2). This process was repeated until these team members reached consensus that the English translation was representative of the original intent of the Spanish document (English v3). Issues of language emerged that required revisions of the Spanish version by the Cuban author, yielding a second Spanish version (Spanish v2). The new Spanish and new English versions were compared again (English v3 and Spanish v3), then sent for peer review in their respective languages. The first author, also bilingual in English and Spanish, responded to the peer review for both versions, resulting in the fourth versions (English v4 and Spanish v4). Copyedits were recommended for both versions. The bilingual translator and the Cuban author partnered in responding to the English and Spanish copyedits, (English v5 and Spanish v5).

The two resulting versions were formatted and proofread side by side, yielding versions in both languages that had been identically reviewed, revised, edited, proofread, and formatted, and were then submitted for publication. This is the scholarly article in Spanish and English, holding the same core message that was the original intent of the authors, that was published in IJPS in December 2021 (Escalona Gonzales et al., 2021).

Multilingual Publication: Challenging the norm and Increasing Scholarship Access

Our team worked together to address the individual and team-level existence of biases and stereotypes. Our partnership approaches to the work allowed for an effective amount of open dialogue to address any concerns or barriers. With these approaches in place, we were able to challenge the norm of English as the dominant language for publication to create a multilingual publication. This article was effectively translated to English, peer-reviewed and copyedited in both languages, and published in both English and Spanish. This not only challenged the norm for publication, but increased scholarship access to those around the world. The article effectively became available worldwide in an open-access journal, at no cost to the authors, in both English and Spanish.

From “What if?” to Reality

With curiosity and determination, our team began with a question of possibility and achieved not only our goal, but also the Model for Partnership-Based Multilingual Publication (see Figure 5). This model offers guidance in challenging the norm of English as the dominant scholarship language by publishing in other languages, honoring original scholarship and presenting it to an expanded audience.

This model emerged with attention to self-work and to team dynamics related to a healthy level of dialogue and discourse, mitigating the influence of bias and stereotypes in the translational process. In addition, the model contains the group’s collective goal that the original document and the translated document hold the same core meaning. Incorporating partnership characteristics (Eisler, 2018a), the model evolved to the visual representation noted in Figure 5.As this is being written, our team is seeking future opportunities for multilingual publishing, and disseminating, through articles and presentations, the knowledge we gained, helping pave the way for other journals to consider multilingual publications.

This project emerged from the curiosity of “What if…” and the collective agreement of the team, including the primary author, to pursue equitable access to scholarship dissemination. IJPS was able to pursue this goal, and had the resources to adapt the methods and processes from the literature to publish a multilingual article. In addition, the intentionality of the team to ensure respectful and responsible translation yielded a new model that attends to self-work and teamwork, focusing on bias and stereotypes that may impede the translational process. Answering the call when curiosity emerges is not only essential for expanding our own learning, but can benefit the globe — in this case, offering a way for a story to be shared from a country which is often filtered out of research dissemination.

Honoring Knowledge around the World

We all have much to learn: from ourselves, from others, and from the world. It is with open minds and curiosity that we will be able to see the knowledge available to us. Starting with one person asking “What if..”, a team supported by the Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies created a new vision and a new path for the journal, with a new intention for equitable access to knowledge dissemination. We have a long way to go to achieve this access with every article or even within every journal issue. However, every little step is a step in the direction of removing filters that inhibit our access to knowledge. As we each participate in the exchange of knowledge, I hope that we all take a role in removing filters and supporting equitable access to global knowledge exchange.

References

Ares, O., Castellet, E., Macule, F., Leon, V., Montanez, E., Freire, A., Hinarejos, P., Montserrat, F., & Ramon Amillo, J. (2013). Translation and validation of ‘The Knee Society Clinical Rating System’ into Spanish. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 21, 2618-2624. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-013-2412-4

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: Key topics in sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press.

Bourke, C. (2020). Unconscious bias and stereotypes: Understanding, identifying, and mitigating these within your workplace. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unconscious-bias-stereotypes-understanding-mitigating-caoimhe/

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 1(3), 185-216.

Country Navigator. (2023). Stereotypes, bias, and culture. https://www.countrynavigator.com/blog/stereotypes-bias-and-culture/

Eisler, R. (2018a). Protecting children: From rhetoric to global action. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 5(3), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v5i1.1125

Eisler, R. (2018b). Contracting or expanding consciousness: Foundations for partnership and peace. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 5(3), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v5i3.1600

Epstein, J., Osborn, R.H., Elsworth, G.R., Beaton, D., & Guillemin F. (2013). Cross-cultural adaptation of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: Experimental study showed expert committee, not back-translation, added value. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68, 360-369. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.013

Escalona González, N., Torres Esperón, J.M., Rodríguez Washington, N., Villafaña Cruz, J.I., & Carasa Alvarez, R. (2021). Perspectives on gender: An investigative study of gender equity in children [Espejuelos para el género: Apuestas investigativas por la equidad en la infancia], Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 8(2), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v8i2.4324

Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., & Beaton, D. (1993). Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 46(12), 1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n

Hendricson, W. D., Russell, I. J., Prihoda, T. J., Jacobson, J. M., Rogan, A., Bishop, G. D., & Castillo, R. (1989). Development and initial validation of a dual-language English-Spanish format for the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 32(9), 1153–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/anr.1780320915

Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies. (IJPS). (n.d.). Vision and mission. https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/ijps/visionandmission

Johnstone, B., & Andrus, J. (2024). Discourse Analysis (4th Ed). Wiley Blackwell.

King, M. L., Jr. (2018). Letter from Birmingham jail. Penguin Books.

Maneesriwongul, W., & Dixon, J. (2004). Instrument translation process: A methods review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(2), 175-186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x

Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba. (MEDICC). (n.d.) MEDICC. https://medicc.org/ns/about/

Tsang, S., Royse, C., & Terkawi A.S. (2017). Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 11(Suppl 1): S80-S89. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_203_17

University of Minnesota, School of Nursing. (2022). National School of Public Health in Cuba, University of Minnesota strengthen partnership. https://nursing.umn.edu/news-events/national-school-public-health-cuba-university-minnesota-strengthen-partnership

Volkova, T. (2014). Translation model, translation analysis, translation strategy: An integrated methodology. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 154, 301-304. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.167

Wild, D., Grove, A., Martin, M., Eremenco, S., McElroy, S., Verjee-Lorenz, A., Erikson, P., & ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 8(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x

-

This chapter underwent a double-anonymized peer-review process.

↵