Engaging Faculty Experts

Professional Learning Communities

Christopher Johnstone; Neamatallah Elsayed; Dunja Antunovic; Margaret Buchanan; Kelly Meyer; and Jonathan Stuart

One of the most important, if not the most important, functions of higher education is teaching. Despite the critical importance of student learning, however, quality teaching can be elusive, even for experienced professors. In 2020, a group of international colleagues started talking about teaching, and discussed a new idea. Rather than planning another workshop on teaching that would likely be ineffective, why not let teachers talk to one another about their work? Further, why not facilitate conversations with teachers from different areas of the world? Shortly after these conversations, the University of Minnesota (UMN) was recruited by Eva Janebova, an international education advocate working then at Palacky University and now with the Mestenhauser Institute for International Cooperation. At the time, Janebova was overseeing a suite of grants focused on internationalization of higher education. In a rare opportunity, UMN was invited to join a group of European Universities in one of the grants, in which a featured activity was Professional Learning Communities (PLCs). As part of the grant activities, both Gayle Woodruff and Chris Johnstone attended an overview session on how to facilitate Professional Learning Communities, held at the Hague University of Applied Sciences. The session was facilitated by Claudia Bulnes, Eveke de Louw, and Dr. Jos Beleen. This chapter provides an overview of PLCs, describes how they were envisioned for UMN (with partner institution Palacky University), presents participant reflections, and concludes by tying together the work of PLCs and Woodruff’s vision of internationalization of higher education.

What are Professional Learning Communities?

PLCs arose from organizational science theories that identify “learning organizations” as a way of promoting effectiveness. Thompson et al. (2004) note that the ideas of learning organizations evolved in education to reflect communities of teachers, intended to create more collaborative work spaces than are typically afforded to instructors, who often work in professional isolation in their classrooms. PLCs for educators vary widely in how they are implemented, but often share several tenets:

- They meet on a regular basis (Greer, 2023).

- They’re structured so that expertise is shared among members (Greer, 2023).

- They’re intended to foster improved academic experiences for students (Greer, 2023).

- Members often have a shared vision, but the group encourages diverse perspectives on how to reach that vision (Hilliard, 2012; Ning et al., 2015).

- They’re most effective when members are collaborative and accountable to one another for participation (Brown et al., 2014).

Vescio et al. (2008) also note that PLCs allow for ‘‘extensive and continuing conversations among teachers about curriculum, instruction, and student development’’ (Neumann et al., 1996, in Vescio et al., 2008, p. 81). Such conversations rely on facilitation that allows for equitable participation and recognition of the expertise that exists within the community itself. These communities have been found to promote innovation and collaboration among educators (Enthoven & Brujin, 2010) and to create “space” for teachers in which to seek advice from others and reflect on their own practice (Hoaglund et al., 2014). The focus of such communities can range widely, from addressing student outcomes to exploring the culture of teaching and its processes and practices (Ning et al., 2015).

Structure of Educator PLCs

Although there are a range of approaches to PLCs, DuFour and Reeves (2016) suggest that there is generally a predictable pattern to how PLCs are structured for educators. Educator PLCs typically require some initial recruitment of participants, and buy-in by those participants to meet on a regular basis and contribute to the conversations. They usually occur for a designated period of time — often a semester or academic year — and a PLC curriculum is needed to facilitate flow of conversations, focus on topics, etc. Within or after the sessions, participants are generally provided a chance to reflect on their learning. Finally, DuFour and Reeves suggest that there needs to be some form of documentation and a process for participants to contact facilitators or fellow participants if they have further questions or desire further inputs.

What Can Be Gained?

Stoll et al. (2006) note that educator PLCs can have a range of outcomes. For individual participants, outcomes may vary depending on what they hope to achieve, the time they commit to the community, and the supplemental activities they may engage in outside of, but relevant to, the PLC.

Importantly, educators who participate in PLCs can have a ripple effect on their system, in part through the ways in which they rethink their own teaching. Stoll et al. (2006) suggest that while it is not always easy to determine direct impacts on students, as so many inputs contribute to teaching, instructors often feel a greater sense of agency after participating in PLCs. In fact, many PLC outcomes are related more to process than to causal changes in student outcomes. Stoll et al. (2006), for example, suggest that instructors may feel more motivated or satisfied with their teaching roles as a result of PLC participation, which may contribute to student outcomes. Participation may also influence their pedagogical knowledge and their sense of responsibility for student learning. These changes may influence classroom dynamics, but may be difficult to link to actual changes in student learning.

Understanding the potential of PLCs as well as their limitations, the UMN facilitators, led by Woodruff’s vision, established what they believed to be a reasonable approach to PLCs.

Designing UMN PLCs

Because the UMN PLC was grant-funded, there were numerous expectations and aspirations for what it could accomplish, including increased partnerships and mobility among international partners, collaborative research undertakings, and even collaboratively developed summer schools. At the time of its creation, Woodruff had already spent decades in the field of internationalization, and was wise to the limitations of the field. She knew that the hype about increased activity and the metrics that captured these activities often created shallow, unsustainable activity. She was suspicious of the grand narratives of internationalization and the assumption that more activity necessarily meant better activity (Brandenburg & de Wit, 2011). To be clear, she was a proponent of international engagement in higher education. As a scholar of intercultural communication, she saw the importance of people with vastly different experiences communicating in shared space around broadly shared goals.

Woodruff hypothesized that the PLC would work best if it was stripped down and simplified. Her recommendation to the team was to focus on two goals: relationships and teaching. She noted that simple “exposure” to new colleagues in international settings, an approach taken by the grant, was not sufficient to generate numerous new international projects. Instead, she suggested that the first and most important goal of this project would be for people to get to know each other. This focus on relationships was based on her experience, which told her that no matter how much an administrator admonishes faculty to do international work, they will ultimately choose their own paths. Woodruff’s hope was to get people in a room and establish working relationships, which could — but were not expected to — grow into personal relationships. This vision of a relational space bucked the expectations of funders and grantees alike, who were focused on outputs and outcomes. Instead, Woodruff advocated for a focus on process.

To do this, she defined a common focus for the PLC — teaching. Woodruff knew that, despite the grant’s focus on internationalization, prospective participants would have different levels of desire, experience, and expertise with internationalization. Some participants, from both Palacky University and UMN, had zero interest in the purposeful internationalization of their curriculum, but enjoyed a space to meet and discuss ideas with others. Others came to the PLC wanting to expand their research or partnership activities with colleagues from partner institutions. It was not long before these participants found each other and began working together. Woodruff was dedicated to ensuring the space was safe and comfortable for all participants to focus on teaching without pressure to do more. The facilitation team, however, had mixed success with this approach, as the push for “outcomes” was felt throughout the project.

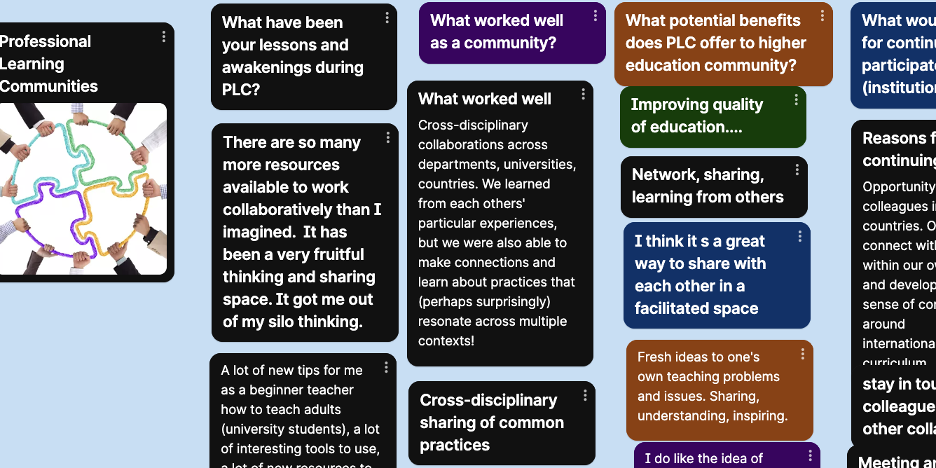

In 2022, the PLC moved from design to implementation. A cohort of ten instructors was recruited from UMN and Palacky University, and monthly meetings were scheduled. The meetings followed the same pattern each time. Each started with a welcome, followed by a 20-minute “share-out” on a topic. Topics included technology in teaching, interactive teaching, the infusion of arts into the curriculum, intercultural communication, and collaborative online international learning (COIL). Share-outs were intentionally limited to 20 minutes because the PLC was not designed as a “training” initiative; the planning team believed that exposure to teaching ideas would stimulate conversation, but did not want them to be the focus of the PLC. After the share-out, instructors joined a breakout room for 45 minutes of facilitated discussion, in which instructors shared ideas, successes, and challenges of teaching, engaging with one another and documenting ideas on a shared padlet (see image below). Sessions ended with individualized reflections and updates on the following session.

In the remainder of this chapter I focus on learnings from the PLC. While Woodruff’s philosophy focused on “process over product,” some products did emerge, and her philosophy to hold space for experts to share their knowledge was upheld. Below, I highlight experiences from PLC participants, and then draw conclusions about the relational approach to internationalization proposed by Woodruff, which was informed by her decades of experience at UMN.

Participant Reflections

Kelly

Coming into the UMN PLC created a feeling of uncertainty and curiosity. I had had previous experiences in PLCs as a classroom teacher, but never at the university level and with others from across the globe. In addition, I was concerned about the letters behind my name. Would an MEd who serves in a coordinator role fit in with this university experience? Through my year-long experience in the PLC, the answer became clear that this was indeed a welcoming place where all experiences and thoughts were valued. The PLC created an even playing field for all involved and broke down the actual or perceived barriers that exist in higher education.

An unexpected outcome of the UMN PLC was the lasting connections that were made with those from our own university. In our daily work, we often describe ourselves as being in silos. We are focused on our own responsibilities and don’t necessarily see or find ourselves in situations where the overlap is evident. Through the PLC, we were able to meet new people with an interest in internationalization and collaboration from our own university. As a concrete example, I continue to meet and stay connected with PLC participants from the departments of Kinesiology and Curriculum and Instruction. We discuss teaching, research, collaborations, and more within this small group of unexpected colleagues across departments.

Margaret

Throughout the pandemic, I was struck by how lonely and isolated we all felt — students, colleagues, family, and friends, even as we all navigated this global event collectively. Teaching was a constant source of anxiety for me; my students were overwhelmed, demotivated, and harsh in their feedback. Teaching conditions and contexts had changed and were unpredictable, and what used to work no longer did. I needed new input, a new community.

The invitation to the PLC could not have been more timely. My implicit goal was to participate in and learn from an international community. My explicit goal was to rediscover joy in teaching. What I didn’t realize at the time was to what extent my joy in teaching intertwined with my self-efficacy beliefs, namely “the extent to which the teacher believes he or she has the capacity to affect student performance” (McLaughlin & Marsh, 1978, p. 84). Bandura (1986) identified four efficacy perceptions in his research on self-efficacy — namely, mastery experiences (teachers’ personal experiences of success or lack of success in the classroom), vicarious experiences, verbal and social persuasion, and emotional and physiological states.

While scholarship highlights that mastery experiences seem to be the most powerful for teacher efficacy (Usher & Pajares, 2008), my post-pandemic mastery experiences of success in the classroom took their time. Instead, I experienced the emotional safety and trust in our organically developing community, which assisted in decreasing pandemic-related teaching anxiety. We might have only met once a month, but the vicarious experiences shared in our small and intimate break-out rooms, or through the short “share-outs,” led to the low-stakes implementation of new techniques or teaching approaches. Armed with a fortified sense of community and a new willingness to take pedagogical risks, I found myself replicating aspects of our PLC in my classes. This culminated in my internationalizing an already existing task in my curriculum. Local students could interact directly with other international students and learn from each other. As a result, my class felt more motivated to learn and share collectively. Students were excited, as was I.

Metrics could hardly capture how I’ve been impacted by my experience with this PLC. Conversations still reverberate and will probably yield results in years to come. This thoughtfully conceived PLC let me experience first-hand how, through community, we can reach out across academic rank, areas of expertise, geographic and linguistic borders to successfully break down boundaries of all kinds.

Dunja

My reasons for joining PLC were two-fold: to engage with colleagues in Europe across disciplines and to build relationships internally within the University of Minnesota with colleagues who care about internationalization. I was particularly interested in conversations with participants from Palacky University, as the Czech Republic is located within the broader Central and Eastern European region I call my home. Through the PLC experience, I learned about new approaches, such as the use of art in medicine (which is relevant for me, as I teach in a Kinesiology program), but I also remembered principles from intercultural communication classes that I could apply in my own courses. For example, I am now more intentional about drawing on local examples and connecting these to global patterns during lectures, and I also created writing discussion assignments that allowed the students to reflect on their own experiences. Importantly, the conversations with colleagues inspired me to articulate new ideas or remember pedagogical strategies that I might not be utilizing now, but that I value greatly.

I also hoped that the PLC would give me the opportunity to meet colleagues across UMN, for several reasons. I started my job during the COVID-19 pandemic, when most of our work was remote. Even though the PLC sessions were also via Zoom, occasional in-person meetings as well as impromptu email exchanges led to meaningful conversations with colleagues beyond the PLC structure. In addition, I knew that UMN had numerous opportunities for international collaboration and internationalization, so I wanted to be in a community with colleagues who also care about these initiatives and could provide further insight. Importantly, I felt that because of my lived experiences, teaching background in international/global perspectives courses, and cross-national comparative research, I would be able to make a meaningful contribution to the conversations. This aspect of my involvement exceeded my expectations, as the members of the PLC greatly enhanced my sense of belonging to the university and to Minnesota.

To summarize, the PLC allowed me to focus on the process of learning, engaging in meaningful conversations, and building relationships. The PLC certainly prompted me to rethink my pedagogical approach, but the most valuable aspect of the experience was in the collaborative reflections on education — within and beyond the classroom.

Jonathan

I was very thankful to be approached back in the spring of 2022 to be part of the UMN and Palacky University PLC cohort. The original invitation link was related to gauging my interest in “internationalization,” but I was mainly excited to be part of an online community of fellow instructors. Originally, I had heard of PLCs at my son’s high school, where one day a week students started the day later so their teachers could meet in small cohorts. I was also approached to co-facilitate a PLC for a local law school during the 2022–23 academic year, so I wanted to take the opportunity to participate in one myself. It turned out to be a very meaningful experience and one I would highly recommend.

As a newer lecturer in the Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development, my primary role is teaching upper-level undergrads in human resource development and general business courses. We are part of the larger College of Education and Human Development, but we don’t have much direct contact, and I looked forward to meeting other faculty at our institution as well as abroad. I also saw a connection between the opportunities afforded by being in a PLC cohort and the concepts outlined in the theory of transformative learning (Mezirow, 2000). The process of dialoguing with others would give me occasions for reflection on my experiences and paradigms.

Prior to our first online meeting, a journal form was sent to participants asking about our goals as we began and then with specific reflections and actions for each of the sessions. Identifying my needs heading into the experience, I wrote “I want to increase my skill in thinking about various identities and learning differences that students bring” and “to connect with other educators and learn from their experiences or perspectives.” My main tension centered on the fact that I could not always be present for the entire sessions, typically on Thursday mornings, due to a class. It was encouraging to hear that any level of attendance would be welcomed.

I learned early on that there were no predetermined outcomes for the group, and that each of us would be contributing and taking away different things. From the wide variety of subjects, I enjoyed the sharing of ideas for novel teaching formats in our Padlet format, learning more about specific opportunities to internationalize my course content, and the resources available to me within the University. In terms of dialogue and relationship development, there were often different people in each breakout Zoom room, so I felt like I got access to all kinds of perspectives. After one of our first meetings, I was surprised by what stuck with me the most. To the question in my PLC journal, “What did I realize in this session in relation to my own educational practice?”, I said “I love teaching because of the people I teach maybe more than the subjects I teach in.” I would venture there was quite a wide variety of things that each person took away or planned to do as result of their participation.

There were three specific impacts that I shared at our final time together. First, I took away classroom tips and a general mindset on how the content of my marketing course could move beyond the US context. Second, participation in the PLC motivated me as a professional instructor in a higher education classroom. I cannot say that this directly impacted my students, but I believe it could be seen in their experience of my teaching. Finally, I deeply appreciated the esprit de corps that I found as part of the PLC between all types of faculty and different disciplines in each institution. I have not found many spaces in higher education where rank and differentiation were diminished through honest dialogue.

Prioritizing the Community in Professional Learning Communities

This chapter provided an overview of how an international PLC for faculty and staff might be structured, and provided a rationale for and research findings about PLCs. While I felt it was important to share a bit about what was learned by participants of the PLCs, the focus of this book is Woodruff’s lasting impact. This case example of PLCs demonstrates why she was so consistently able to promote international initiatives throughout her career. Participants’ experiences focused on the “community” aspect of the PLC. From the very start of the project highlighted in this chapter, Woodruff maintained that relationships and communities had to be the most important aspect of the work we undertook. Although she retired before the project completed, participant comments demonstrate that she was successful in her approach.

Woodruff’s impact on internationalization at UMN and beyond is felt most profoundly outside of the typical narratives and imagery of internationalization. You will not find her signing Memoranda of Understanding sitting in front of flags, nor would you ever hear her pressing to increase participation in international programs if she was not sure the programs were of high quality. Woodruff’s vision and application of international work was people-centered. In her career, she was a learner, doer, and connector. For those of us who facilitated or participated in the PLC, she was also a mentor on how to construct international activities that were meaningful and worthwhile for participants. (Thank you, friend.)

References

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Brandenburg, U., & De Wit, H. (2011). The end of internationalization. International Higher Education, (62). https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2011.62.8533

Brown, B. D., Horn, R. S., & King, G. (2018). The effective implementation of professional learning communities. Alabama Journal of Educational Leadership, 5, 53-59.

DuFour, R., & Reeves, D. (2016). The futility of PLC lite. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(6), 69-71.

Enthoven, M., & de Bruijn, E. (2010). Beyond locality: The creation of public practice‐based knowledge through practitioner research in professional learning communities and communities of practice. A review of three books on practitioner research and professional communities. Educational Action Research, 18(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650791003741822, DOI: 10.1080/09650791003741822

Greer, S. (2023) Professional Learning Communities (PLCs). Kentucky Department of Education. Available at: https://education.ky.gov/school/stratclsgap/Pages/plc.aspx (Accessed: 12 November 2023).

Hilliard, A. T. (2012). Practices and value of a professional learning community in higher education. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 5(2), 71-74.. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v5i2.6922

Hoaglund, A., Birkenfeld, K., & Box, J. (2014). Professional learning communities: Creating a foundation for collaboration skills in pre-service teachers. Education, 134(4), 521-528.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Marsh, D. D. (1978). Staff development and school change. Teachers College Record, 80(1), 1-18.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass.

Newmann, F. M., & Associates (1996). Authentic achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual quality. Jossey-Bass.

Ning, H. K., Lee, D., & Lee, W. O. (2015). Relationships between teacher value orientations, collegiality, and collaboration in school professional learning communities. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 337-354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9294-x

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221-258.

Thompson, S. C., Gregg, L., & Niska, J. M. (2004). Professional learning communities, leadership, and student learning. RMLE Online, 28(1), 1-15.

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 751-796.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004