20 Accessibility and European E-Resources Acquisition

Katie Gibson

Introduction

Universities, and more specifically university libraries, have been taking significant actions to improve the accessibility of the resources they offer to their students, faculty, and staff. But what does it mean to be accessible? In its resolution agreement with the University of Montana, the US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights says that accessibility “means that individuals with disabilities are able to independently acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services within the same timeframe as individuals without disabilities, with substantially equivalent ease of use” (“Resolution Agreement,” n.d.).

As the resolution agreement indicates, many accessibility initiatives begin with a complaint, lawsuit, or Office of Civil Rights inquiry, and are resolved through consent decrees or other settlement agreements. Examples of such agreements include the University of California, Berkeley 2013 settlement agreement with Disability Rights Advocates; Penn State’s 2013 resolution agreement; and the University of Montana’s resolution agreement with US Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (DeLancey and Ostergaard 2016). Each of these came with mandated changes and standards, and require regular reporting on changes and improvements to accessibility.

Inherent in these agreements, and in universities’ larger initiatives to become more accessible, is an acknowledgment of the social model of disability. Where the medical model treats disabilities “as a condition residing within certain people, as a malfunction or medical problem” (Schmetzke 2007, 454), the social model recognizes disability as “the restriction of activity based on a social context that overlooks the existence of people with impairments” (Kazuye Kimura 2018, 428). Universities and libraries are taking more proactive approaches to addressing these issues in the acquisitions process, but they still tend to drop off librarian’s radar screen as we take on additional responsibilities (Schmetzke 2015).

Library resources often pose significant barriers to a student’s success. A 2010 study found that 80% of databases evaluated presented accessibility barriers (Tatomir and Durrance 2010), including slow loading times and inaccessible visual materials. Perhaps the most pervasive issue across database platforms is inaccessible PDF full-text, but other issues exist as well, such as availability of alternative text on images, problematic heading structures, and interactive elements (Pionke and Schroeder 2020). Even articles in disability studies journals from major publishers have been found to have PDF accessibility issues (Nganji 2015). And this is not an issue exclusive to journal article databases. eBook platforms are also problematic, especially those carrying academic eBooks (Mune and Agee 2016). When students can’t access the full array of library resources, “the first step in information literacy–—the ability to critically locate and select appropriate articles—is being compromised” (Dermody and Majekodunmi 2011, 157). The inaccessibility of library resources is disabling our students’ access to information.

While it is important for all subject liaison librarians to understand and consider accessibility issues when adding to their libraries’ collections, European Studies librarians have the added complication of working with international materials, navigating differences among European Union (EU) law and the laws of individual European countries, and addressing varying levels of awareness, receptiveness to requests to modify licensing language, and willingness by providers to address accessibility issues as they arise. This chapter will broadly survey literature related to accessibility in library acquisitions, look at web accessibility standards in the US and EU, examine methods for addressing accessibility in the acquisitions process, and provide recommendations for European Studies librarians new to the world of accessibility. It will also present interviews with select European vendors.

Accessibility in the United States

As more academic institutions in the US address the accessibility of their collections, the need to be familiar with standards and laws increases. Librarians at any point in their career need to be familiar with Sections 504 and 508 of the Workforce Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. The Workforce Rehabilitation Act of 1973, also known as the Rehabilitation Act, prohibits programs that receive federal funding (including academic institutions) from discriminating on the basis of disability (Section 504), and requires that federal agencies make their information technologies accessible to both employees and the public (Section 508) (Willis and O’Reilly 2018; “Section 508 Surveys and Reports: Main Overview Page,” n.d.). The Americans With Disabilities Act applies to academic institutions, “prohibiting discrimination and requiring accommodations for full participation in education” (DeLancey and Ostergaard 2016, 181).

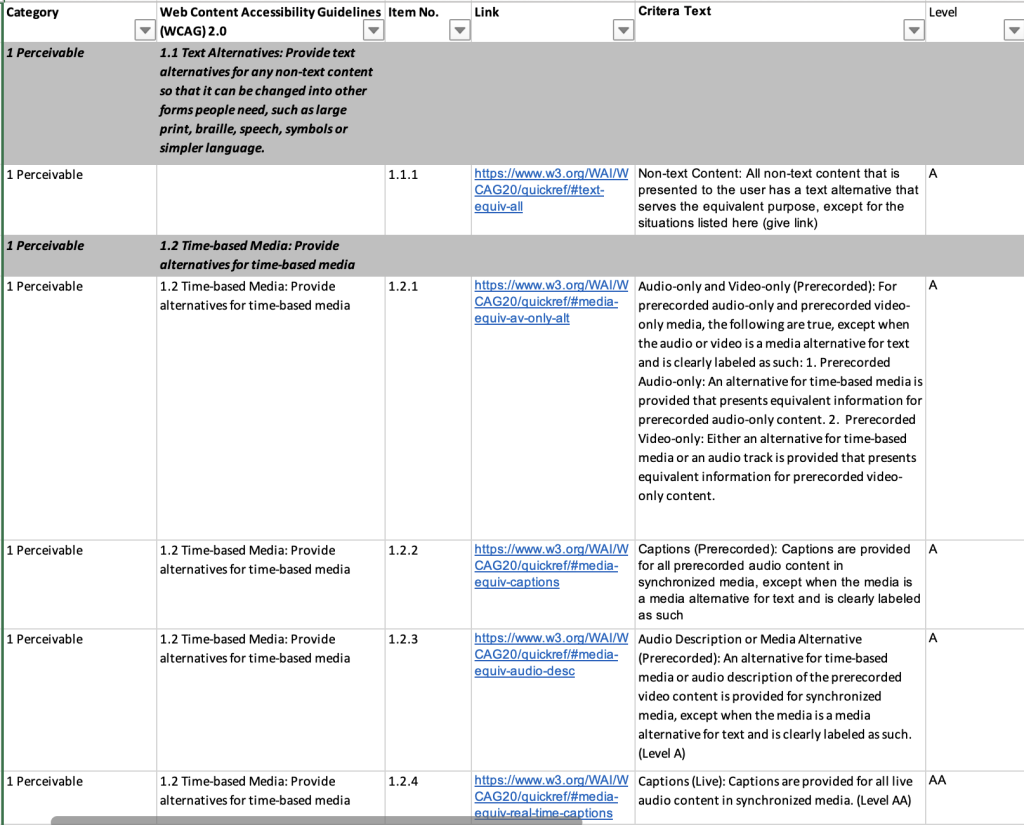

But how is accessibility measured? Perhaps the best-known and most widely used standards to assess accessibility are the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) in their various iterations. WCAG released a working draft of the version 2.2 standards in May 2021, and a working draft of the 3.0 standards in July 2021. The standards are divided into sections assessing how perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust the web content is (“Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1” 2018). Beneath these sections are individual compliance standards in levels ranging from A to AAA, with AAA being the most rigorous. For web content to achieve AAA compliance, it must meet the requirements of all A, AA, and AAA level standards listed for that category.

WCAG standards have faced criticism. Standards that take a checklist approach turn accessibility into a box to be marked off and “fixed” rather than shifting perspectives and creating larger systemic change (Kazuye Kimura 2018). And, even close adherence to WCAG standards does not guarantee full accessibility to a web resource (Nganji 2015). Some argue that accessibility determinations should take into account how disabled people use a site (Kelly et al. 2013), because a fully accessible site does not guarantee that it’s easily usable in the practical sense. Despite these critiques, however, the use of WCAG standards remains widespread. And because they are intended to be international standards, their use is not exclusive to the US. As outlined in the next section, they provide the basis of many accessibility standards throughout Europe.

Accessibility in Europe

Cross-European efforts to mandate web accessibility are more recent than those in the US. While some countries within the EU had laws mandating internet accessibility in the early 2000s, the EU itself lacked binding centralized coordination. The eEurope 2005 plan from the European Commission stated that “by 2004, member states should have ensured that basic public services are interactive, where relevant, and accessible for all” (Thorén 2004, 102), and the 2010 Digital Agenda for Europe required that “public websites and services…that are important to enable people to take full part in public life” meet WCAG 2.0 standards (European Commission 2010, 26). Similar to Section 508 in the US, the plan encouraged public sector entities to take accessibility into account at the point of acquisition. Even with these recommendations, guidelines, and targets, however, large discrepancies between requirements still existed in different countries, and levels of web accessibility were low (Ferri and Favalli 2018).

The great variations in country-specific legislation in the early 2000s illustrate the difficulty of centralized coordination. The Stranca Act, passed in Italy in 2004, “protects each person’s right to access all sources of information and services independent of disability” (“Digital Accessibility Laws in Italy,” n.d.), and uses standards based on Section 508 and WCAG 1.0 to set accessibility requirements for public sector websites. The French Law N° 2005-102, specifically articles 47 and 78, “broadly require that public services that are provided by federal, state and local agencies be accessible to individuals with disabilities” (“French Accessibility Requirements” 2010). The deadline in the law, however, was a moving target, getting pushed back several times. France uses the Référentiel Général d’Accessibilité pour les Administrations (RGAA) standard, which is based on WCAG 2.0 with the addition of a few other requirements, and has a second widely recognized accessibility certification, the AccessiWeb label. Created by the BrailleNet advocacy organization, AccessiWeb standards are based on a reorganized form of WCAG standards, and while not required by law, the label “is widely recognized within France as a certification mark that demonstrates a high degree of compliance” (“French Accessibility Requirements” 2010). The status of this project, however, is in question, with the website inaccessible as of this writing. In Spain, section five of law 34 of 2002 required public sector websites to be accessible by the end of 2005 in terms defined by standard UNE 139803:2004, created by the Spanish standards organization AENOR (“Spanish Accessibility Requirements” 2010). Germany passed an Act on Equal Opportunities for Disabled Persons in 2002, and the Federal Ministry of the Interior and the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs subsequently created the Creation of Barrier-Free Information Technology ordinance, commonly referred to as BITV (Barrierefreie Informationstechnik-Verordnung). The ordinance mandates that federal web content and services be accessible and pass the BITV conformance test (BITV-Test, B. I. K., n.d.), which is also based on WCAG standards. And in July 2021, Germany passed the Barrierefreiheitsstärkungsgesetz, which implements the European Accessibility Act (EAA).

This disorganization, along with the use of a variety of standards and voluntary participation, began to change when the EU signed the 2008 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which lays out “the role technology can play as a tool to promote the human rights of people with disabilities, and their participation and inclusion in society” (Ferri and Favalli 2018, 2). As it moved to implement the UNCRPD, on April 17, 2019 the EU passed Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and the Council, more commonly known as the European Accessibility Act (EAA). Applying to both private and public institutions, the act mandates accessibility of all types across the EU, addressing web accessibility and many information technologies relevant to libraries, including eBooks and eJournals, vendor catalogs and ecommerce sites, and eReaders (Madden and How 2019). ETSI, a European standards organization, set the standards by which accessibility will be measured under the act, and these map to and reference WCAG 2.1 AA standards (“Accessibility Requirements for ICT Products and Services” 2019).

The EU maintains a complete list of the EAA in national laws. There are many critiques of the EAA. The timeline is long; the directives were mandated to become part of national laws in EU countries by 2022, and countries must start applying them by 2025 (Drabarz 2020). The Act exempts small companies, and does not include the built environment in its accessibility mandates (“EDF Analysis of the European Accessibility Act” 2019). And major services such as health care, transportation, housing, and home appliances are excluded from the act (Drabarz 2020). Still, with vendors and publishers now working to improve the accessibility of their products, it is an opportune moment for librarians to communicate our institutions’ accessibility requirements and needs. European Studies librarians are in a position to facilitate this process.

Accessibility in Acquisitions

All of these concerns should and do affect the acquisition of electronic resources. As a European Studies librarian, the role you can play in working toward accessibility in the acquisitions process is in some part shaped by the institutional structure in which you work. A large R1 (R1 Doctoral Institutions) with a large acquisitions department will function very differently than a smaller college or medium-sized research library. The spectrum of liaison subject librarian involvement in purchasing can range from making simple purchase requests and having initial inquiry discussions with vendors to leading price negotiation and licensing discussions. No matter the role you end up playing, ideally, you’ll need to know about Voluntary Product Accessibility Templates (VPATs), accessibility language in licensing, collection development policies, and resources available to learn more about accessibility in order to best work within your acquisitions structure to provide the most accessible resources to your users.

VPATS and their drawbacks

A VPAT is a template created by the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) and the General Services Administration in the US to “assist Federal contracting and procurement officials in fulfilling the market research requirements specified in Section 508” (US Social Security Administration, n.d.). VPATs are completed by a vendor in order to document the accessibility of their product. They can be publicly available on a vendor’s website, or be nonexistent for a particular resource. With the European Accessibility Act and the established standards to determine accessibility in Europe, ITI has also developed EN 301 549, a template for mapping to European accessibility standards (Information Technology Industry Council 2020).

Requiring a VPAT from vendors is one of the most common starting places when considering accessibility in acquisitions. Being a standardized template, however, it is far from perfect. Information provided by the vendor can be at least partially inaccurate. DeLancey (2015) evaluated VPATs, and found that 80% were accurate using automated testing to confirm information provided by the vendor. Additionally, the standardized format hasn’t evolved with changing accessibility standards (DeLancey 2015), and the format might lead vendors to focus on meeting minimal technical standards rather than on true accessibility in how the product is used (Kazuye Kimura 2018). Even given these problems, however, VPATS are often still required as the starting point for discussions of accessibility with a vendor. And given how new the templates are to Europe, a European Studies librarian might be called on to explain them to a vendor who does not currently provide such documentation.

Licenses and procurement

One of the more active roles libraries can take in improving the accessibility of their resources is to require accessibility to be addressed in licensing agreements. In 2009, the American Library Association (ALA) passed a resolution recommending that libraries require vendors to comply with Section 508 and WCAG 2.0 guidelines, perform regular testing or require vendors to provide accessibility testing reports, and ask funders to provide adequate resources to make the recommendations possible (Council of the American Library Association 2009). Such licensing language should require vendors to:

- comply with all applicable accessibility laws,

- grant the right to create accessible versions of content, and

- promptly address accessibility issues with their products as they arise (Rodriguez 2020, 152-53). Additionally, product updates and improvements should not compromise accessibility (Rodriguez 2020, 153).

Sample language for licensing agreements is available from a wide variety of institutions, including the Library Accessibility Alliance (a partnership between the Big Ten Academic Alliance (BTAA) and the Association of Southeastern Research Libraries), the LIBLICENSE project hosted by the Center for Research Libraries, and the Library of Congress. Each can be customized to meet the needs and requirements of a specific institution. Negotiating these additions is often challenging (Pionke and Schroeder 2020), especially with smaller European vendors who might be unfamiliar with accessibility or are beginning their process of working to comply with EU accessibility standards.

European Studies librarians at larger institutions are not likely to be involved in licensing negotiations undertaken by an acquisitions department, while at a small institution, a liaison subject librarian might be expected to fully take on this role. No matter the institutional context, you’ll need to be familiar with your institution’s procurement process and its legal requirements or recommendations for licensing. Does it require specific accessibility language to be added to all licenses? Does it have a minimum level of accessibility required to be met before procurement? Is an Equally Effective Alternative Access Plan (EEAAP) required when procuring a resource that does not meet minimum accessibility standards? Such a plan would put into place an action plan for addressing alternative access options before a user reports inaccessible content. If one is required, which entities on campus work with the vendor to create the EEAAP? Will any new resource undergo an accessibility review, either in the library or by a campus accessibility team? A liaison subject librarian is not expected to undertake all of these activities, but a thorough knowledge of the procurement process and the accessibility requirements of an institution will provide you with the footing to begin conversations on these topics with vendors in the initial inquiry process.

Collection development policies

One thing squarely in the role of the liaison subject librarian is writing a collection development policy. Accessibility language is increasingly being included in licenses, but it has yet to be incorporated into many libraries’ collection development policies (Schmetzke 2015). Wherever possible, subject liaisons should update such policies to reflect the accessibility statements and policies of the larger institution. These are often internal documents, but the process of updating them to include accessibility emphasizes their importance to the internal audience. They can be cited when constituents push for inaccessible resources, and can provide continuity in the event of turnover in positions. Examples of such language can be found at SUNY Albany and Columbia University. Generally included is a statement of the institution’s commitment to accessibility and to the prioritization of accessible resources, and some explanation of the process for requesting equally effective alternative access to materials.

European Vendors

The issues outlined above became clear when we interviewed people involved in accessibility work and in library markets in Europe. Respondents emphasized the importance of understanding differences in each country, and how such differences can lead to varied approaches to providing accessible content. In Italy, there has been a proactive approach to addressing accessibility concerns. The Stranca law was updated in 2018 to bring it in line with EAA guidelines. The Fondazione LIA, founded in Italy in 2011 as a project of the Italian Publishers Association, provides accessibility consulting, training, and accessibility testing and certification to publishers. Its work closely aligns to existing international standards such as EPUB, ONIX (for metadata), and WCAG 2.1. It has since also gone on to create partnerships across borders, including with the Federation of European Publishers. Its partnership with the German publishing organization Börsenverein resulted in the creation of accessibility guides specifically for publishers working to create born-accessible content.

While Italy has had an accessibility mandate in law prior to the EAA, this is not the case in France. The vendor representative we interviewed outlined the many political considerations affecting accessibility. The French Parliament was discussing EAA implementation in 2022, but with a change in presidents and a parliamentary election currently in process as of this writing, discussions were placed on a back burner. Publishers and platform providers were waiting to see the results of legislative action before acting, and had various concerns, including over the issue of funding and the large costs associated with making their eBooks accessible. Would government funding be provided to help with these efforts? They also wondered whether back-listed titles would be included in any mandates. According to the vendor we interviewed, publishers worked to negotiate a delay on making backlist titles accessible, as doing so would require a considerable investment in time and resources. The idea of just withdrawing titles from eBook availability has been floated as a possibility in case there are no deadline extensions for backlist titles. Either way, smaller publishers’ electronic publishing is at risk because of costs, which will ultimately have an impact on bibliodiversity. At some point, the additional costs of creating born-accessible electronic content is likely to be passed on to the clients. The EAA was enacted into French law in March of 2023 (“LOI N° 2023-171 Du 9 Mars 2023,” n.d.).

This vendor also discussed the need for clear and specific communication about an institution’s accessibility needs, especially by librarians in the US. While sales representatives at the firm don’t have specific training on accessibility, they understand that it’s a growing concern. But with accessibility standards being large and complex, the vendor expressed a need to hear concrete information from librarians about which standards and requirements should be prioritized.

Recommendations for European Studies Librarians

To those new to the profession or to accessibility in acquisitions, there can be a lot to learn, and it’s common to feel overwhelmed. As one interview participant emphasized, however, accessibility is the responsibility of every participant in the value chain (Anonymous. 2022). With that in mind, what follows are concrete, actionable recommendations that can make a difference in improving the accessibility of resources in libraries. It’s crucial to remember that, in following these recommendations, you are removing barriers that disable user access to our research resources and facilitating the success of all students and faculty.

Learn about your institution

Learn about your institution’s accessibility requirements and procurement process. What level of accessibility for electronic resources does your institution require? What is your collection development policy? What is the procurement process and policy? Do new purchases go through accessibility checks?

Identify key partners on campus. Work with your disability services department to learn about your local community needs. Are there student groups that you can bring into the process? Is there a person in information technology services responsible for accessible technology? Does your library have a liaison responsible for reaching out to these groups?

Build a relationship with your vendors

When working with vendors, it’s essential to communicate your institution’s needs in concrete and specific terms, including what accessibility standards your institution must meet. Where necessary, point to current European legal requirements for accessibility, and communicate usability and accessibility feedback you get from patrons. If you don’t acquire a product due to accessibility concerns, provide that feedback to the vendor. Find out if the company has an accessibility point person. In addition, take the time to understand the vendor’s point of view so you can best work together to resolve issues as they arise beyond the licensing process.

Document your work

As you complete these recommendations, document your findings. You can use your notes to build a checklist or resource documentation for other colleagues, or as a tool in training new librarians at your institution.

Stay current with publishing trends in Europe

Accessibility in Europe is in flux, especially as countries work to create legislation in line with the EAA. Staying current with publishing trends in Europe, especially as they relate to accessibility, not only builds a librarian’s knowledge, but facilitates communication with vendors. Whether it’s attending open vendor forums hosted by the European Studies Section of the Association of College & Research Libraries, reading the newsletters of organizations like the Fondazione LIA (which is provided in English), or keeping current with new development with trade organizations like the Federation of European Publishers, there are many avenues to keeping informed of new developments.

Conclusion

Utilizing available resources is extremely helpful in feeling less overwhelmed at the amount of information available as you work to improve your knowledge about accessibility and to incorporate accessibility into your acquisitions process.

Takeaways

It is essential to frequently consult key resources for this important work:

- Library Accessibility Alliance Testing: Results of accessibility testing of library resources completed by consulting companies on behalf of the BTAA and the Association of Research Libraries. Includes vendor responses to testing results when available.

- BTAA sample license language: Sample standardized license language for accessibility.

- LIBLICENSE: Hosted by CRL; provides a model license template, licensing vocabulary list, licensing terms and descriptions, and a discussion forum.

- Library of Congress Terms and Conditions for License of Electronic Resources: A model license for electronic resources; includes a section on accessibility.

- Disabilities and Libraries Toolkit, University of North Carolina: A toolkit covering all aspects of disabilities in the library, including identity, facilitators and barriers to access, planning with the library community, and inclusion and accessibility in action.

- Accessibility Information Toolkit for Libraries: From the Ontario Council of University Libraries; covers public services, procurement, and law and administration, and provides additional resources. Some information is specific to Canada.

- VPAT Templates: Templates for VPAT 2.4 for Section 508 standards, EU standards, and WCAG standards.

- WCAG 2.1 Standards: The full WCAG 2.1 standards, with explanations of each and how each can be met.

References

“Accessibility Requirements for ICT Products and Services.” 2019. ETSI. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/301500_301599/301549/03.01.01_60/en_301549v030101p.pdf.

Anonymous. 25 May 2022. Interview with accessibility consultant.

BITV-Test, B. I. K. n.d. “BIK BITV-Test | BITV-Test.” Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.bitvtest.eu/bitv_test.html.

Council of the American Library Association. 2009. “Purchasing of Accessible Electronic Resources Resolution.” July 15, 2009. https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/1061.

DeLancey, Laura. 2015. “Assessing the Accuracy of Vendor-Supplied Accessibility Documentation.” Preprint. Western Kentucky University. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlts_fac_pub/23.

DeLancey, Laura, and Kirsten Ostergaard. 2016. “Accessibility for Electronic Resources Librarians.” Serials Librarian 71 (3/4): 180-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2016.1254134.

Dermody, Kelly, and Norda Majekodunmi. 2011. “Online Databases and the Research Experience for University Students with Print Disabilities.” Library Hi Tech 29 (1): 149-60. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831111116976.

“Digital Accessibility Laws in Italy.” n.d. Level Access. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://www.levelaccess.com/accessibility-regulations/italy/.

Drabarz, Anna. 2020. “Harmonising Accessibility in the Eu Single Market: Challenges for Making the European Accessibility Act Work.” Review of European & Comparative Law 43 (4): 83-102. https://doi.org/10.31743/recl.9465.

“EDF Analysis of the European Accessibility Act.” 2019. European Disability Forum. http://www.edf-feph.org/content/uploads/2021/02/edf_analysis_of_the_european_accessibility_act_-_june_2019_2_0.doc.

European Commission. [2010]. “Digital Agenda for Europe.” Accessed November 13, 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0245:FIN:EN:PDF.

Ferri, Delia, and Silvia Favalli. 2018. “Web Accessibility for People with Disabilities in the European Union: Paving the Road to Social Inclusion.” Societies 8 (2): 40-40. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020040.

“French Accessibility Requirements.” 2010. Level Access. November 30, 2010. https://www.levelaccess.com/french-accessibility-requirements/.

Information Technology Industry Council. 2020. “Voluntary Product Accessibility Template (VPAT): EN 301 549 Edition Version 2.4.” https://www.itic.org/dotAsset/22d0c5ca-e78a-4b5d-bea3-3fad313ae924.doc.

Kazuye Kimura, Amy. 2018. “Defining, Evaluating, and Achieving Accessible Library Resources: A Review of Theories and Methods.” Reference Services Review 46 (3): 425-38. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-03-2018-0040.

Kelly, Brian, Jonathan Hassell, David Sloan, Dominik Lukeš, E. A. Draffan, and Sarah Lewthwaite. 2013. “Bring Your Own Policy: Why Accessibility Standards Need to Be Contextually Sensitive.” Ariadne: A Web & Print Magazine of Internet Issues for Librarians & Information Specialists, no. 71 (July). https://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/71/kelly-et-al/

“LOI N° 2023-171 Du 9 Mars 2023 Portant Diverses Dispositions d’adaptation Au Droit de l’Union Européenne Dans Les Domaines de l’économie, de La Santé, Du Travail, Des Transports et de l’agriculture (1) – Légifrance.” n.d. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000047281777.

Madden, Heidi, and Sarah How. 2019. “Welcome to the VUCA World! The Frankfurt International Book Fair 2019. Part 2.” Duke University Libraries Blogs (blog). December 10, 2019. http://blogs.library.duke.edu/blog/2019/12/10/welcome-to-the-vuca-world-the-frankfurt-international-book-fair-2019-part-2/.

Mune, Christina, and Ann Agee. 2016. “Are E-Books for Everyone? An Evaluation of Academic e-Book Platforms’ Accessibility Features.” Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship 28 (3): 172-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2016.1200927.

Nganji, Julius T. 2015. “The Portable Document Format (PDF) Accessibility Practice of Four Journal Publishers.” Library & Information Science Research 37 (3): 254-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.02.002.

Pionke, Jj, and H. M. Schroeder. 2020. “Working Together to Improve Accessibility: Consortial E-Resource Accessibility and Advocacy.” Serials Review 46 (2): 137-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2020.1782630.

“Resolution Agreement.” n.d. U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.umt.edu/accessibility/docs/FinalResolutionAgreement.pdf.

Rodriguez, Michael. 2020. “Negotiating Accessibility for Electronic Resources.” Serials Review 46 (2): 150-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2020.1760706.

Schmetzke, Axel. 2007. “Introduction: Accessibility of Electronic Information Resources for All.” Edited by Axel Schmetzke and Elke Greifeneder. Library Hi Tech 25 (4): 454-56. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830710840428.

———. 2015. “Collection Development, E-Resources, and Barrier-Free Access.” Advances in Librarianship 40 (July): 111-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0065-283020150000040015.

“Section 508 Surveys and Reports: Main Overview Page.” n.d. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://www.ada.gov/508/.

“Spanish Accessibility Requirements.” 2010. Level Access. December 28, 2010. https://www.levelaccess.com/spanish-accessibility-requirements/.

Tatomir, Jennifer, and Joan C. Durrance. 2010. “Overcoming the Information Gap: Measuring the Accessibility of Library Databases to Adaptive Technology Users.” Library Hi Tech 28 (4): 577-94. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831011096240.

Thorén, Clas. 2004. “The Procurement of Usable and Accessible Software.” Universal Access in the Information Society 3 (1): 102-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-003-0077-3.

U.S. Social Security Administration. n.d. “SSA Guide to Completing the Voluntary Product Accessibility Template.” Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.ssa.gov/accessibility/files/SSA_VPAT_Guide.pdf.

“Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1.” 2018. June 5, 2018. https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/.

Willis, Samuel K., and Faye M. O’Reilly. 2018. “Enhancing Visibility of Vendor Accessibility Documentation.” Information Technology and Libraries 37 (3):12-28. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v37i3.10240.

Link List

(accessed December 1, 2023)

- https://www.w3.org/TR/wcag-3.0/.

- https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html.

- https://www.section508.gov/manage/laws-and-policies/.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0245:FIN:EN:PDF.

- https://www.boersenverein.de/beratung-service/barrierefreiheit/.

- https://ocul.on.ca/accessibility/.

- http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/bgg/gesamt.pdf.

- https://www.aenor.com/.

- https://www.ada.gov/ada_intro.htm.

- https://www.bmas.de/DE/Service/Gesetze-und-Gesetzesvorhaben/barrierefreiheitsstaerkungsgesetz.html.

- https://www.bitvtest.de/start.html.

- https://btaa.org/library/reports

- https://btaa.org/library/reports/library-e-resource-accessibility—standardized-license-language.

- https://library.columbia.edu/about/policies/collection-development-policies-strategies.html.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/NIM/?uri=CELEX:32019L0882.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L0882.

- https://cedi.unc.edu/dl-toolkit-home/.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0263:FIN:EN:PDF.

- https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/301500_301599/301549/03.02.01_60/en_301549v030201p.pdf.

- https://acrl.ala.org/ess/.

- https://fep-fee.eu/.

- https://www.fondazionelia.org/en/.

- https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000809647/.

- https://www.lib.iastate.edu/about-library/policies/collections-development/collection-development-policy#Accessibility.

- http://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L7/CONG/BOCG/A/A_068-13.PDF.

- http://liblicense.crl.edu/.

- https://libraryaccessibility.org/resources.

- https://libraryaccessibility.org/testing.

- https://www.loc.gov/acq/devpol/lc-model-license.pdf.

- https://www.loc.gov/acq/devpol/lc-model-license.pdf.

- https://www.numerique.gouv.fr/publications/rgaa-accessibilite/.

- https://www.agid.gov.it/it/design-servizi/accessibilita.

- https://library.albany.edu/policies/collection-development#diversity–accessibility–equity–and-inclusion-in-collections.

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/index.html.

- https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/new-in-22/.

- https://www.itic.org/policy/accessibility/vpat.

- https://www.itic.org/policy/accessibility/vpat.

- https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/.

- https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/.

- https://www.eeoc.gov/rehabilitation-act-1973-original-text.

About the Author

Katie Gibson is a Humanities and Area Studies Librarian at Miami University (Ohio), where she serves as liaison to Asian & Asian-American Studies, Black World Studies, French & Italian Studies, German Studies, Individualized Studies, International Studies, Latin American Studies, Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, and Spanish & Portuguese Studies. She received her MLS from Indiana University. Her research interests include library services for diverse student populations, accessibility of library resources, and digital humanities.