22 Bibliodiversity

Sebastian Hierl and Claude H. Potts

Introduction

Bibliodiversity—a neologism still wanting a precise definition—is at the heart of an area specialist’s work collecting, preserving, and providing access to diverse cultural texts. The term bibliodiversidad (bibliodiversity) is said to have been first coined by a group of Chilean publishers when founding the Editores Independientes de Chile (Independent Publishers of Chile) collective in the late 1990s (Valencia 2018, 47). However, this point of origin has been disputed by Spanish publishers who are members of the Comisión de Pequeñas Editoriales (Commission of Small Publishers)—a working group of the Asociación de Editores de Madrid (Publishers Association of Madrid)—and who launched the journal Bibliodiversidad in 1999. Formed in 2002, the Alliance internationale des éditeurs indépendants (International Alliance of Independent Publishers) has also made a significant contribution in disseminating and promoting this term in various languages, especially at its international meetings (e.g., the Declarations from Dakar in 2003, Guadalajara in 2005, and Paris in 2007) and in all its communications (Alliance internationale des éditeurs indépendants, n.d.). The Alliance has further helped the term become internationally accepted and to spread rapidly within the French-speaking world. As the term bibliodiversity gains popularity in the English-speaking world, it is also becoming widely adopted and the focus of international initiatives undertaken by publishing collectives, UNESCO, and the European Writers’ Parliament.

Proponents of bibliodiversity agree that the publishing ecosphere is fundamentally under threat from overproduction and from financial concentration, which favors the predominance of a few large publishing groups and the pursuit of large profit margins. The market is characterized by a huge imbalance, with commercial logic vastly prevailing over the intellectual adventurousness that is characteristic of small, independent, or unconventional publishers. For academic libraries, the imbalance between commercial and independent publishers is exacerbated by institutional preferences for digital over print. Faced with the prevalence of print publishing in Europe, the spectrum of viewpoints collected and preserved by academic libraries risks becoming impoverished without the intervention of the librarian or vendor. In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, North American library organizations such as The Collaborative Initiative for French Language Collections (CIFNAL), the German-North American Resources Partnership (GNARP), and the Slavic and East European Materials Project (SEEMP) issued more than a dozen resolutions stressing the importance of the continued acquisition of print materials, see: “European Studies Statement on Collection Development, Access, and Equity in the Time of COVID-19, Issued by CIFNAL, GNARP, and SEEMP.” The joint statement by groups within the Center for Research Libraries highlights how critical the voices of marginalized, minority, and vulnerable communities, new social movements, and transnational authors are advancing research of and learning about the linguistic and cultural diversity of the European continent. Bibliodiversity endeavors to ensure diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) as it strives for equilibrium in the publishing ecosphere.

“Just as biodiversity is an indicator of the health of an ecosystem, the health of an eco-social system can be found in its multiversity, and the health of the publishing industry in its bibliodiversity,” explains feminist writer and publisher Susan Hawthorne (Hawthorne 2014a, 13). For Françoise Benhamoua, a French specialist of economics of art and literature, bibliodiversity is more than just variation in the number and kinds of book titles: “If we look at what that means in biodiversity we see the extremely simple idea that if you have several species but some are present in huge numbers while others are very scarce, the ones with many units are likely to eat or prevail over the others” (Hawthorne 2014a, 14). In the strictest sense, it is small independent publishers who are most at risk as attributes of bibliodiversity are constituted by theme (or topic), language, format, genre, place of publication, sexual orientation/identity, political position, and other characteristics often exclusively taken up by these publishing houses who work on the margins. Conversely, it is possible to locate traits of bibliodiversity within the catalogs of large commercial publishers, but wholly insufficient to rely on them alone.

Why Bibliodiversity Matters

According to Hawthorne, “Publishing is a social, cultural and transformative activity” (Hawthorne 2014b). When a publishing ecosystem is dominated by a few large companies that are driven by profit seeking, the readers’ choice and access to new ideas, the plurality of ideas, and the dissemination of knowledge is restricted. Only popular authors, topics, or culturally or economically dominant groups and ideas will draw sufficient attention in the marketplace to generate the double-digit profit margins sought by large commercial publishing conglomerates. In The Business of Books, publisher André Schiffrin eloquently describes the danger of market concentration and the essential role of the independent publisher in ensuring a diversity of voices, ideas, and new knowledge:

It is only in books that arguments and inquiries can be conducted at length and in depth. Books have traditionally been the medium in which two people, an author and an editor, could agree that something needed to be said, and for a relatively small amount of money, share it with the public. [. . .] Books can afford to go against the current, to raise new ideas, to challenge the status quo, in the hope that with time an audience will be found. The threat to such books and the ideas they contain—what used to be known as the marketplace of ideas—is a dangerous development not only for professional publishing, but for society as a whole. (Schiffrin 2001, 171-172)

In order for such innovative and challenging books—of which perhaps only a few hundred or thousand copies may have been printed—to remain available and to find an audience with time, libraries must collect them. For research institutions, it is not enough to simply provide access to licensed content, especially in this new era of network interdependence and heightened resource sharing. For libraries to maintain rich, varied, and deep collections, librarians must actively build their collections and seek out challenging and innovative books, and thus have the resources, both in terms of time and financial means, to do so. To accomplish this goal of bibliodiversity, librarians must build a network of suppliers and acquire publications across the spectrum of formats. Just as a library cannot rely on and focus its acquisitions on the largest publishing houses, even if they offer the most efficient means of access or discounts (as only they can afford them), efficiencies in the acquisitions process cannot be the sole deciding factors in the selection of vendors. Rather, cultivating relationships with essential partners will ensure that core publications for the library are acquired reliably and efficiently, and free up the area specialist’s time to search for the marginal and small press publications, which are not always covered by the larger vendors.

A European studies librarian may work with their library’s main suppliers on streamlining and rationalizing, even automatizing work flows, to acquire the publishing output of major publishers. This will free up the selectors’ time to actively search for and ferret out publications that are not carried or known by the main vendors. The final selection decision and the assignment of funds, however, must remain the responsibility of the librarian, who is ultimately responsible for the long-term curation of the collections in accordance with their institutional strategic objectives.

Vendors may not always be aware of the output of small, independent publishers or of publications by local societies and museums. Especially in Europe, local societies, museums, and banks publish valuable information about local archaeological excavations and historical sites, with formats ranging from booklets to major exhibitions catalogs. Because of their format and limited print runs, these may not always be obtained on the market and carried by vendors. Volumes in the monographic series West-Vlaamse Archaeologica (West Flanders Archaeology), for example, may not be readily included in approval plans, but contain crucial information on the Roman presence in the Low Countries and on trade routes and cross-cultural influences in the Middle Ages. In Italy, publications are often sponsored by banks and local foundations that may not have an incentive to sell their catalogs, making them difficult to obtain. Even recent publications are sometimes printed in smaller runs, as they are destined mostly for their local market. Examples include Palazzo della Banca d’Italia a Firenze: restauro della facciata monumentale by Cristina Donati, published in Rome in 2016 by Italy’s Central Bank, the Banca d’Italia, as well as publications by local government entities or museums, such as Catania: archeologia e città: il progetto opencity banca dati, GIS e WebGis, edited by Daniele Malfitana, Antonino Mazzaglia, Giuseppe Cacciaguerra, et al., Catania: [Istituto per i beni archeologici e monumentali], 2016; or La necropoli romana di Via Beltrami ad Arsago Seprio: 1975-2000: 25. anniversario dalla scoperta: atti del convegno e mostra fotografica, documentaria, published by the Civico museo archeologico in Arsago Seprio, 2003.

Publications such as these are not frequently requested by North American scholars, but if they have not been acquired by North American libraries, they remain invisible and inaccessible to scholars in Canada and the US. In some cases, calling the publishing institution to ask for a copy or picking one up in person may be the only means of access, as it is generally not in a vendor’s economic interest to supply single copies or small numbers of hard-to-obtain titles. Responsible vendors who are partners in a library’s mission to build strong collections will go out of their way to help, and may be willing to lose money on one title or a smaller number of publications, as long as the overall mix is profitable, but this is not always the case and cannot simply be assumed. The knowledge and the responsibilities of the European studies librarian matter.

In the same manner, the publication format impacts the level of bibliodiversity in library collections. Even at the time of writing, it is mainly the largest academic presses and commercial publishers in North America and Northern Europe that offer eBooks (numerous smaller presses and publishers in Southern and Eastern Europe offer extensive lists of eBooks, but the scholarly eBook has gained more traction in Northern Europe)—and even they do not offer all of their monographic publications in electronic format. Thus, only a subset of the total publishing output is available in electronic format. The 2021 report on Italian book publishing for the Frankfurter Buchmesse (Frankfurt Book Fair) indicates that there were 1,263,257 titles in paper format in print in Italy, compared to 499,562 eBook titles (L’Associazione Italiana Editori 2021). Focusing or limiting a library’s acquisitions to electronic-only publications severely restricts access to intellectual arguments and creative expression.

The notion of bibliodiversity is also linked to the open access movement: access to a broad range of publications and scholarship, and the right to publish and control the distribution of one’s work. The gradual shift toward open access publishing in scholarly communication has been difficult, and a long time in the making. As illustrated by the Joint COAR-UNESCO Statement on Open Access (United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization and Coalition of Open Access Repositories 2016) and the Jussieu Call (Jusieu Call 2017), the scholarly community is still searching for a viable open access model that is truly inclusive. It is incumbent upon librarians with selection responsibilities at academic libraries—indeed, at all libraries— to support decolonized open access models and to foster an environment in which all voices are represented and heard. Through our purchase decisions and our promotion of publications and resources in our information literacy and research guides, librarians participate in and shape scholarly communication. To ensure bibliodiversity, it is not sufficient for librarians merely to acquire publications by small presses and marginalized authors, or in lesser spoken languages and diverse formats. Librarians must also actively contribute to making these resources accessible by sharing their unique collections and fostering a scholarly communication system that is democratic and inclusive. A publishing ecosystem dominated by a handful of large, private, profit-driven conglomerates is antithetical to such democratic and inclusive access, and selectors at academic libraries have a role to play in helping to establish innovative and alternative publishing models. The fundamental role of the selector is to ensure that the information that they purchase, accept as a gift, link to, or exchange is worthy of preservation, to make that information accessible to scholars, and to ensure that the collections they steward are as rich and varied as possible, while matching their institution’s mission and priorities. Through their selections, enhancements to discovery and access, and research guides and information literacy courses, librarians foster acceptance by the scholarly community of the information they provide, and are key contributors to establishing confidence in more inclusive publishing schemes.

From Small Independent Presses to Fanzines

Curating and growing a bibliodiverse library collection may seem an insurmountable task, especially when many librarians feel they have insufficient resources to even begin. Identifying unique and culturally valuable works outside of the mainstream publishing sector requires time and perseverance. Once you begin to look more closely at your home collection, however, you may realize that it already contains recognizable elements of bibliodiversity. You might encounter works from small presses and underrepresented voices captured in some of the lesser-taught European languages such as Catalan, Dutch, Hungarian, Icelandic, Occitan, Welsh, or Yiddish. You might learn that many of the core authors you’ve been collecting for years are, in fact, immigrants from other continents living in Europe, such as feminist writer, philosopher, and literary critic Hélène Cixous or postmodern philosopher Jacques Derrida, both born and raised in Algeria but naturalized as French citizens in their teens.

Even if most are no longer independent today, small literary presses have brought to the world 20th-century masterpieces such as James Joyce’s Ulysses (France, 1922), Bruno Schultz’ Sklepy cynamonowe (Poland 1934; The Street of Crocodiles), Günter Grass’ Die Blechtrommel (Germany 1957; The Tin Drum), Mercè Rodoreda’s La plaça del diamant (Spain 1962; In Diamond Square), and Svetlana Aleksievich’s U vojny ne ženskoe lico (Belarus 1985; War’s Unwomanly Face), amid countless others. The second largest Italian publisher on the trade market, Giulio Einaudi Editore—now part of the Gruppo Mondadori, controlled by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi—was established in Turin in 1933 by a group of anti-fascist intellectuals including Leone Ginzburg, Massimo Mila, Norberto Bobbio, and Cesare Pavese. After the liberation of Italy, the publishing house succeeded in promoting new fiction writers such as Natalia Ginzburg, Elio Vittorini, Italo Calvino, and Elsa Morante, at the same time continuing political reflection and giving ample space to non-fiction, as exemplified in the works of Primo Levi and Antonio Gramsci (Treccano Enciclopedia on line, n.d., s.v. “Einàudi, Giulio”). In 1950s France, Les Éditions de Minuit—first founded during the war as a publishing house of the Resistance—gave rise to the experimental nouveau roman (new novel) associated with writers such as Nathalie Sarraute, Claude Simon, Michel Butor, Marguerite Duras, Robert Pinget, Claude Ollier, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Samuel Beckett (Simonin 1996, 59). In 1957, Minuit took a tremendous risk by publishing Pour Djamila Bouhired, an account of the trial of a 22-year old female member of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) who was tortured and condemned to death in Algiers. It was among the first books to denounce the practice of torture by the French Army, and this example of littérature d’action, or littérature engagée (committed literature), as it would later be named by Jean-Paul Sartre, resulted in the woman’s release (Simonin 1996, 59).

The mere fact that an independent publishing house produces a book does not in itself ensure bibliodiversity. When you browse your library’s shelves, however, you will find that many of the most original and daring publications are in fact published by independents with autonomous editorial policies and free from external interference. In Italy, independent publishers control 40% of the market, which Marco Zapparoli—co-founder of Marcos y Marcos and president of the Associazione degli Editori Indipendenti (ADEI; Association of Italian Independent Publishers)— attributes to robust readership and a symbiotic harmonization with independent bookstores (Zapparoli 2021, 7). It is no surprise that one of Italy’s best-selling novelists, Elena Ferrante (Edizioni e/o), and one of the most esteemed living philosophers, Giorgio Agamben (Quodlibet), both publish with independent publishing houses. As defined by the International Alliance of Independent Publishers, independent publishers are “originating publishers.” Through their often-innovative publishing choices, freedom of speech, and financial risk-taking, they participate in discussions and distribution, and in development of their readers’ critical thinking. In this regard, they are key players in bibliodiversity (Alliance internationale des éditeurs indépendants, n.d.).

Identifying independent publishers is not always straightforward. Few self-identify as such, and many have been or are being absorbed the larger publishing groups and international conglomerates—as was recently the case with Les Éditions de Minuit being acquired by Groupe Madrigall (Libération 2021). Nevertheless, it is prudent to assume that most university presses are independent, as are the publishing arms of scholarly societies such as the Sociedad de Estudios Medievales y Renacentistas (SEMYR; Society for Medieval and Renaissance Studies) in Salamanca. The information-rich catalogs and ephemeral publications of museums, libraries, archives, and foundations are all produced independently, but these institutions often lack adequate distribution channels. With the demise of most international library exchange programs by the early 2000s, it has become even more difficult for North American research libraries to encounter let alone acquire such predominantly print publications, often out of reach even for in-country vendors. Most valuable for their unique and exclusive content are the research reports, incidental publications, and departmental papers of universities (Spohrer and Hazen 2007, 156). Institutes and research centers such as the Institut d’Estudis Catalans (Institute of Catalan Studies) in Barcelona have moved their publications online, where they are openly accessible, but much of the gray literature they disseminate remains accessible only by exchange or direct purchase.

Until the advent of the internet, a viable form of alternative publishing in Europe and North America was the zine, or fanzine (a portmanteau of fan and magazine). These non-commercial, non-professional magazines, flourishing from the 1970s through the early 1990s, were published in small numbers and created, reproduced, and distributed by the authors themselves, in opposition to “the mainstream” represented by both the state and the entire commercial domain (Šima and Michela 2020, 8). Contemporary scholars analyze fanzines—made possible by the advent of inexpensive photocopiers—because they offer new insights from a “history from below”perspective. With historical precedent in the Dada periodicals of Zürich and Berlin, these alternative narratives, presented on amateurly designed pages, are an important source for studying social history in the late socialism and post-socialism periods in Czechoslovakia and in the successor states Czech and Slovak Republics, as well as in almost all other European nations (Šima and Michela 2020, 8). Elke Zobl, Austrian researcher and founder of the now inactive Grrrl Zine Network, discussing zine maker Mimi Nguyen, posits that queer, trans folk, and feminist zines (or femzines) and their transnational network provide a “culturally productive, politicized counterpublic” in which people can experiment with ideas, articulate their own views, and describe experiences otherwise suppressed by mainstream society (Zobl 2009, 10). While the proliferation of blogs and e-zines (or webzines) has rapidly superseded the booklet format, xeroxed zines persist, providing an analog alternative that reflects and resists cultural and political devaluation by dominant narratives (Borodacheva, n.d.)

If your library has collected comics or graphic novels, the vantage points proffered in some of these publications might be considered bibliodiverse and could enrich the library’s holdings on sensitive subjects such as the dark legacy of the Spanish Civil War and the ensuing Franco regime. Antonio Hernández Palacios’ Euskadi en llamas (Euskadi in Flames) and Groka Gudari, first published between 1979 and 1987 but reprinted in 2019 by boutique graphic publisher Ponent Mon in Tarragona, are examples of how popular genres can critically approach historical trauma long before it is addressed by the academy. For Europe in particular, comics and graphic novels play an important role beyond entertainment and diversion. Le Monde journalist Alain Beuve-Méry reported that in 2006 the comics sector was the third largest part of the European francophone book market, after literature and children’s books (McKinney 2008, 6). Though dominated by five major publishing houses or groups, independent publishers of bandes dessinées (comic books)—like L’Association, founded in 1990 by seven young comics artists including Jean-Christophe Menu, David B., and Lewis Trondheim—have succeeded in finding an outlet for their work while resisting the commercialization of the format. L’Association was among the first to publish Joann Sfar, considered one of the most significant graphic novelists of the new wave of Franco-Belgian comics, and Marjane Satrapi, an Iranian-born French author whose autobiographical “comic books”confront the brutalities of Muslim fundamentalist regimes in the Middle East. In the Fumetto (literally “little puff of smoke”), as it is referred to in Italy, comics artists, such as Pietro Scarnera and Bianca Bagnarelli, continue a century-long tradition of tackling serious topics with word bubbles and drawings. In all corners of Europe, and largely through the support of independent presses, the format continues to thrive and evolve, reflecting the region’s complexities through provocative reworkings of history, politics, and social issues.

At the extreme and expensive end of the bibliosphere are rare books, manuscripts, and other primary sources which are typically shelved in special collections. Artists’ books and other printed ephemera, however, occupy a murky area between the rare and the circulating, and have recently found themselves as centerpieces in the evolving liberal arts curriculum. In her article “Teaching with Artists’ Books,” Louise Kulp argues that artists’ books can effectively teach critical thinking, encourage discovery of interdisciplinary connections, and prompt the consideration of relationships among text, image, and form (Kulp 2015, 101). While contemporary artists’ books can be traced back to illuminated manuscripts, they should not be confused with the more opulent genre known as livres d’artiste, which surfaced in Europe and the Americas in the early 20th century. Instead, artist books can be defined as a unique work (often in multiple copies) “created by an artist in book format, self-published or published by galleries, limited editions to sometimes none, inexpensive to exclusive collector’s items” (Manmeet 2020, 4).

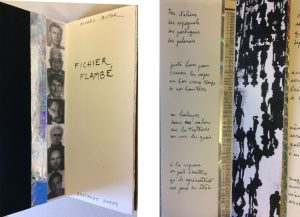

There are many examples of such books. Arrebato Libros, an independent bookstore in the heart of Madrid, promotes the works of book artists such as Roberto Equisoain, whose innovative “books” repurpose previously published works in their presentation of reflections, puns, and fragments of conversations. Al Manar Éditions, a Parisian publisher that focuses on art and literature from both shores of the Mediterranean and also produces artists’ books, provides a creative platform for underrepresented postcolonial voices, such as Rita Alaoui and Abdellatif Laâbi, both originally from Morocco. And one of more than a dozen collaborations between experimental writer Michel Butor and artist Bertrand Dorny, Fichier flambé (Paris 1997; File on Fire) is a collage-book of metallic papers, photographic cutouts, pages from a Parisian phonebook, and a handwritten poem. This provocative artist’s book functions as a playful call for tolerance in the wake of xenophobic anti-immigration legislation and racist violence in France.

Beyond the Vendor and Discovery in Unlikely Places

While approval plans are vital for the timely and steady acquisition of recently published monographs, even the best vendors cannot profile all the books and ephemeral materials of interest to academic communities. As a result, librarians for Europe and other regions of the world have devised strategies to supplement the coverage of their approval plans. Faculty, students, and library colleagues provide some of the best suggestions for materials of interest. Book reviews and announcements, particularly in social media platforms like blogs, formerly Twitter (now X), and Instagram, are a limitless source for new publications. Managing such a voluminous amount of information can be achieved by setting up feeds and periodically checking them in RSS readers.

A traditional method of ensuring more complete coverage is by consulting the national bibliographies. The Swiss Book, for example, the national bibliography of Switzerland published by the Swiss National Library, lists the country’s entire output of information media: books, maps, music scores, electronic media and multimedia, periodicals, newspapers, annual publications, series, and gray literature. National bibliographies are often available on the website of the respective national libraries, and many can be found in the research guides of the European Studies Section (ESS).

Arguably more important than the national bibliographies are specialized associations and vendors. NordLit and NORLA, for example, promote selections of Nordic literatures that may be of interest to readers beyond the region. In addition, many European libraries see their own catalogs as serving as advanced specialized bibliographies. Some examples include the libraries of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (German Archaeological Institute), located in Rome and Athens and elsewhere which analyzes journals and monographs in their specialized fields at great depth. The Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History and the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (Art History Institute in Florence) undertake such analysis for publications in art history and architecture, and the German Historical Institutes do the same for a number of subjects. There are also the highly specialized bibliographies, such as Projekt Dyabola (subscription resource), which covers art history, the ancient world, and classical studies; the Byzantinische Bibliographie (subscription resource) for Byzantine studies; and L’Année Philologique (subscription resource) for classics.

Catalogs and announcements from vendors besides your institution’s primary one are also a rich source of information, and may reflect differences in profiling. Despite global trends toward vendor consolidation, the importance of vendor/librarian relationship is crucial in ensuring bibliodiversity. Vendors based in Europe are usually the best contacts for small presses, facilitating payment and speedy acquisition, even if they may not list a certain publication in their database. By ordering through the vendor and not through the publisher or a bookstore, we articulate our unique or evolving interests. Once vendors learn of an interest, they can begin adding similar titles to their online catalogs and offerings, extending awareness of previously unknown titles to peer libraries. Academic conferences and symposia, whether online or in-person, can also enrich our awareness of materials which may not be considered core to our approval plans. Past programs and forums sponsored by the Association of College & Research Libraries’ European Studies Section (ESS) and predecessors the Slavic and Eastern European Studies Section (SEES) and the Western European Studies Section (WESS), including Documenting Sexual Dissidence and Diversity in France, Italy and Spain, Beyond Tintin: Collecting European Comics in the U.S., and Refugee Scholars and Academic Libraries in the Twentieth Century and Today, aim to expand our knowledge of bibliodiverse themes and genres.

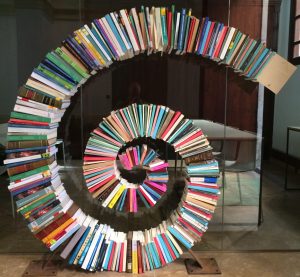

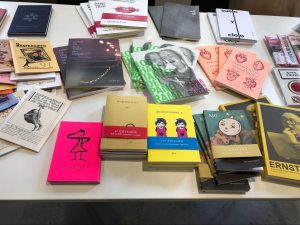

According to the International and Area Studies Collections In the 21st Century (IASC21), a community of area studies librarians and archivists, travel to the regions of responsibility is a time-tested strategy practiced by international and area studies librarians in order to maintain subject expertise (“authority”) and effective networks (“currency”) (International and Area Studies Collections In the 21st Century 2016). Through foreign travel, librarians can make the one-of-a-kind purchases that distinguish and develop their respective collections. They can also initiate, establish, and nurture their international networks, through which they can support the work of others—most notably the students and researchers of their universities (International and Area Studies Collections In the 21st Century 2016). Book fairs abroad provide opportunities for encountering titles and publishers which may have not made it into a vendor catalog. With author talks, presentations, and curated displays, these fairs promote publications in ways virtually impossible by other means. While commercial book fairs such as LIBER, which alternates between Madrid and Barcelona, and the Frankfurter Buchmesse (Frankfurt Book Fair) can provide the impetus and justification for an acquisition trip, it is often outside of the convention halls that the most worthwhile discoveries are made. Lesser known fairs and festivals—including the Leipziger Buchmesse in Germany; the Salon de la Revue, a showcase for French and Italian cultural journals which takes place in Paris every October; and Più libri più liberi, the fair for independent presses held in Rome every December—offer opportunities for librarians to converse with and learn about smaller publishers.

Besides the chance to make valuable connections at book fairs, research institutes, libraries, and archives in Europe, travel offers a golden opportunity to purchase or identify bibliodiverse material of potential interest. Independent and specialized bookshops such as Librería Berkana in Madrid or Prinz Eisenherz Buchladen in Berlin, both of which focus on LGBTQ+ publications, provide a concentration and level of expertise unavailable through other channels/venues. Mikrofest is an example of one of the few online bookstores with a similar focus, listing titles from over 40 smaller, independent Danish publishers. While some bookstores are now owned and operated by large publishing conglomerates, independent bookstores such as Livraria Letra Livre in Lisbon act as clearing houses for small presses and sell new, used, and out-of-print titles in the fields of literature, human sciences, anthropology, gender studies, social history, politics, and sociology.

Many of these bookstores sell hard-to-find materials like artists’ books, zines, pamphlets, and comics. In Paris’ Latin Quarter, an independent bookshop that cannot be missed by those who collect for Francophone Africa and the diaspora is that of legendary Éditions Présence Africaine (EPA), publisher of Aimé Césaire, Edouard Glissant, Marie NDiaye, and Ousmane Sembène, among others. In 2021, EPA, along with dozens of publishers, bookstores, and local organizations, launched the first-ever Salon du livre africain de Paris, which focused on independence and freedom of expression on the continent.

The physical, cultural, social, and intellectual spaces of bookstores not only showcase publications of note, but promote, contextualize, and hierarchize them in an organic way that static lists, websites, and Google cannot. The moment we set foot into a bookstore, we begin to learn through its publishing stock what is and is not popular and valued amongst its community of readers. We recognize what is in our own libraries and, more importantly, what is missing. If, as Jorge Carrión writes in Librerías (Bookshops), every bookshop is a condensed version of the world specialized shops embody the profoundness of these distinct worlds, fields, and disciplines making up what we call our world (Carrión 2013, 21).

A Self-Assessment of Your Collecting

For all of these reasons, it is essential that European studies librarians periodically and critically review their own decisions, supply chains, and preferences for disciplines, subjects, languages or cultural origins, and other subjective criteria, as well as the vendors, formats, and means of access they use. Bibliodiversity, published by the International Alliance of Independent Publishers, cites the main indicators of bibliodiversity as variety, balance, and disparity (Benhamou and Peltier 2011, 28).

Considering these indicators, the following are questions to ask yourself and to periodically assess:

- Of the books, journals, and other materials you acquire for your library, how many are published by independent presses?

- How much can you responsibly spend on e-resources vs. print publications, and what is the right balance for your collection and institution?

- Are you adequately covering cultural diversity for the countries you collect?

- There are more than 400 minorities, ethnic groups, and nationalities in Europe, with approximately 125 languages spoken; which do you collect? (Federal Union of European Nationalities, n.d.)

- How much do you acquire in English vs. vernacular languages?

- Are you collecting material in languages spoken in Europe but outside of the Indo-European family, such as Arabic, Beur, Berber, Euskadi/Basque, Finnish, Hungarian, Kurdish, Maltese, the Romani languages, Sinhalese, Tamil, Turkic languages, and Wolof?

- Are you collecting material in endangered European languages such as the Celtic languages, Corsican, Frisian, Friulian, Occitan, Picard, Romansh, Sardinian, Sorbian, Yiddish, and so on?

- How many books in your collection are written by immigrant writers?

- How many of the publications you acquire are by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) or LGBTQ+ writers?

- Are you collecting all political perspectives? Should you document extreme views and preserve them for posterity? Which mix is responsible and represents a healthy diversity of ideas?

- Is your primary vendor able to supply all the publications you want? How do you verify that your vendor is reliably covering the market? Are there other vendors, perhaps specialized vendors or bookstores, that could complement your main vendor’s coverage? If you work with a number of vendors, how do you avoid duplication?

- Are you coordinating the shared collection responsibility with other partner libraries in a consortium? How are you gaining access to the publications collected by these partners or other institutions?

- Are you including non-traditional formats in your collection policy, such as ephemera, AV materials, popular culture formats (e.g., comics, zines, genre literature, and telenovellas), and other material culture objects?

- When digitizing rare and archival materials, do you make them freely accessible? While it may make sense to work with publishers to digitize your unique holdings, how do you avoid locking these holdings behind a paywall that only select institutions will be able to afford?

- Are you providing links to a select number of specific institutional repositories, or do you rely on a relatively comprehensive search engine, site, or network?

- Are you archiving websites, data, or other online ephemeral content?

Answers to these questions will depend on your institution; budget; personal knowledge of the languages, countries, or subcultures; and ability to identify the appropriate mix of vendors to supply and support your collection development policy—assuming that policy is a thoughtful, carefully calibrated one that reflects the priorities of your institution and your financial means. While we each aspire to being as inclusive and supportive of bibliodiversity as possible, all of us, even selectors at the largest academic libraries in the world, cannot collect or catalog everything, and must set priorities. Your institution’s collection development policy will structure these priorities, back you up in case of difficult decisions or questions, and further guide and formalize your sharing agreements.

While bibliodiversity may be an unfamiliar term for many, the concept it signifies has been around for as long as librarians have been curating library collections. It requires a critical and periodic assessment of both the materials we firm order and those we receive automatically on approval plans and standing orders, taking into consideration many of the factors described in the self-assessment above. Being more conscious of bibliodiversity may require taking your work deeper and becoming more proactive, yet every step forward, from institutions of all sizes, will help the collective effort, as we evolve from disconnected and siloed libraries to a shared collection reflective of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging.

Key Takeaways

- Bibliodiversity is at the heart of an area specialist’s work collecting, preserving, and providing access to cultural texts of diversity.

- Bibliodiversity endeavors to ensure diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) as it strives for equilibrium in the publishing ecosphere.

- Dominance of the publishing ecosystem by a few large companies that are driven by profit seeking restricts readers’ choice and access to new ideas, the plurality of ideas, and the dissemination of knowledge.

- For libraries to maintain rich, varied, and deep collections, European studies librarians must actively build their collections and seek out challenging and innovative books, and must have the resources, both in terms of time and financial means, to do so.

- Focusing or limiting a library’s acquisitions to electronic-only publications severely restricts access to intellectual arguments and creative expression.

- The notion of bibliodiversity is inseparably linked to openness: access to publications, access to scholarship, and access to publish and distribute one’s work.

- Once you begin to look closer at your home collection, you may begin to realize that your collections already possess recognizable elements of bibliodiversity.

References and Recommended Readings

Alliance internationale des éditeurs indépendants. n.d. “Presentation & orientations.” Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.alliance-editeurs.org/-presentation-orientation,068.

Association of College & Research Libraries. “ACRL Statement on Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and the Print Collecting Imperative.” Last modified October 8, 2020, https://acrl.ala.org/acrlinsider/acrl-statement-on-equity-diversity-inclusion-and-the-print-collecting-imperative

L’ Associazione Italiana Editori. 2021.“Rapporto sullo stato dell’editoria in Italia 2021.” Last modified October 20, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.aie.it/Buchmesse2021.aspx.

Benhamou, Françoise, and Stéphanie Peltier. 2011. “How Should Cultural Diversity Be Measured? An Application Using the French Publishing Industry.” Bibliodiversity | Bibliodiversity Indicators, no. 1. https://www.alliance-editeurs.org/IMG/pdf/Bibliodiversity_Indicators.pdf.

Borodacheva, Masha. n.d. “New East zines—New East 100,” The Calvert Journal. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/8406/new-east-100-zines-diy-freedom-expression.

Carrión, Jorge. 2013. Librerías. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

Center for Research Libraries. 2020. “European Studies Statement on Collection Development, Access, and Equity in the Time of COVID-19, Issued by CIFNAL, GNARP, and SEEMP.” Last modified August 20, 2020. https://www.crl.edu/news/european-studies-statement-collection-development-access-and-equity-time-covid-19-issued-cifnal.

Federal Union of European Nationalities, n.d. “Map of Minorities & Regional and Minority Languages In Europe.” Language Diversity. Accessed on November 1, 2021. http://language-diversity.eu/en/products/lehrmaterial/karte-der-minderheiten-sowie-der-regional-und-minderheitensprachen-europas.

Hawthorne, Susan. 2014a. Bibliodiversity: A Manifesto for Independent Publishing. North Melbourne, Vic. : Spinifex Press.

Hawthorne, Susan. 2014b. “Independent Publishing as the Source of Bibliodiversity,” Publishing Perspectives, November 26, 2014. https://publishingperspectives.com/2014/11/independent-publisher-bibliodiversity.

International and Area Studies Collections In the 21st Century. 2016. “IASC21 Statement: The Value of International Travel for Area Studies Librarians.” Last modified November 16, 2016. https://sites.utexas.edu/iasc21/2016/11/16/iasc21-statement-the-value-of-international-travel-for-area-studies-librarians.

Jusieu Call. 2017. “Jussieu Call for Open Science and Bibliodiversity.” Accessed June 21, 2022. https://jussieucall.org.

Kulp, Louise A. 2015. “Teaching with Artists’ Books: An Interdisciplinary Approach for the Liberal Arts.” Art Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America 34, no. 1: 101-123. https://doi.org/10.1086/680568.

Libération. 2021. “Gallimard s’offre les Éditions de Minuit.” June 23, 2021. https://www.liberation.fr/culture/livres/gallimard-soffre-les-editions-de-minuit-20210623_TR6IIONQ6FGNVKENGNCFVPTSKE.

Manmeet, Sandhu. 2020. “Artist Books and Art Zines: Past and Present.” Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art & Design 4, no. 2: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.21659/cjad.42.v4n201.

McKinney, Mark. 2008. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Project MUSE. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/9875.

New Shape of Sharing: Networks, Expertise, Information: An online Forum on European Librarianship (January 11 – April 19, 2021). Accessed June 21, 2022, http://ucblib.link/sharing2021.

Schiffrin, André. 2001. The Business of Books: How the International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read. London: Verso.

Šima, Karel, and Miroslav Michela. 2020. “Why Fanzines? Perspectives, Topics and Limits in Research on Central Eastern Europe.” Forum Historiae 14, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.31577/forhist.2020.14.1.1.

Simonin, Anne. 1996. “La littérature saisie par l’histoire: Nouveau Roman et guerre d’Algérie aux Éditions de Minuit,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales no. 111-112 (March): 59-75: https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1996.3168.

Spohrer, James H., and Dan C. Hazen, eds. 2007. Building Area Studies Collections. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz.

Treccano Enciclopedia on line. n.d. s.v. “Einàudi, Giulio.” Treccani. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giulio-einaudi.

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization and Coalition of Open Access Repositories. 2016. “Joint COAR-UNESCO Statement on Open Access.” Last modified May 9, 2016. files/coar_unesco_oa_statement-1.pdf.

Valencia, Margarita. 2018. “La edición independiente Consideraciones generales sobre el caso colombiano,” Trama & Texturas, no. 37: 41-56.

Zapparoli, Marco. 2021. “Independence, Coherence, Bibliodiversity. Publishers.” Last modified 15 February 2021. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ngHBNzJb1Sgjky-UTlmtXP3n01nPKJwf/view

Zobl, Elke. 2009. “Cultural Production, Transnational Networking, and Critical Reflection in Feminist Zines.” Signs 35, no 1: 1-12. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.1086/599256.

Link List

(All accessed June 2022)

- https://editmanar.com.

- https://www.alliance-editeurs.org.

- https://www.antennebooks.com.

- https://www.arrebatolibros.com.

- http://www.associazioneadei.it.

- https://zines.barnard.edu/zine-libraries

- https://acrl.ala.org/ess/conferences/past-conferences/wess-conferences/past-wess-conference-programs/2015-wess-sees-program.

- https://editoresmhttps://editoresmadrid.org/comision-pequenas-editoriales-2adrid.org/comision-pequenas-editoriales-2.

- https://www.biblhertz.it.

- https://www.bookpride.org.

- https://www.degruyter.com/database/BYZ/html?lang=en.

- http://www.lescahiersdecolette.com.

- https://www.crl.edu.

- https://www.codexfoundation.org.

- https://www.crl.edu/programs/cifnal.

- https://editoresmadrid.org/comision-pequenas-editoriales-2.

- https://contemporarysmallpress.com.

- https://www.danskeforlag.dk/om-danske-forlag/medlemmer.

- https://www.dainst.org/en/dai/meldungen.

- https://acrl.ala.org/ess/conferences/past-conferences/wess-conferences/past-wess-conference-programs/documenting-sexual-dissidence-and-diversity-in-france-italy-and-spain.

- http://www.leseditionsdeminuit.fr.

- https://www.presenceafricaine.com.

- https://www.edizionieo.it.

- https://www.edizionindipendenti.it.

- https://allea.org.

- https://acrl.ala.org/ess.

- https://www.crl.edu/news/european-studies-statement-collection-development-access-and-equity-time-covid-19-issued-cifnal.

- https://fep-fee.eu/-Members-.

- https://www.bdangouleme.com.

- http://2020.poeticofestival.es.

- https://www.buchmesse.de.

- https://www.maxweberstiftung.de/en/institute.html.

- https://www.crl.edu/programs/gnarp.

- https://www.einaudi.it.

- http://www.grrrlzines.net.

- https://www.islit.is/en/icelandic-publishers/stafrof/a.

- https://www.ipgbook.com.

- https://www.indiebook.de.

- https://publicacions.iec.cat.

- https://sites.utexas.edu/iasc21.

- https://www.internationalpublishers.org.

- https://www.khi.fi.it.

- http://www.kurt-wolff-stiftung.de.

- https://about.brepolis.net/lannee-philologique-aph.

- https://www.lassociation.fr.

- https://www.lautrelivre.fr

- https://www.librairiesharmattan.com.

- https://www.fanzino.org.

- https://www.leipziger-buchmesse.de.

- https://lerdevagar.com.

- Les Éditions de Minuit.

- https://www.federacioneditores.org/liber.php.

- https://www.ecumedespages.com/infosprat.php.

- http://www.libreriaberkana.com.

- https://www.letralivre.com.

- https://twitter.com/LaCalders.

- https://marcosymarcos.com.

- https://mikrofest.dk.

- http://www.mottodistribution.com.

- https://ucblib.link/sharing2021.

- https://www.islit.is/en/projects/nordlit-the-nordic-literature-centers.

- http://norla.no/en/pages.

- https://forleggerforeningen.no/om-oss/medlemsforlag.

- https://plpl.it.

- http://www.ponentmon.com.

- https://feiradolivro.porto.pt.

- https://prinz-eisenherz.buchkatalog.de.

- http://www.dyabola.de.

- https://www.publishersglobal.com.

- https://www.quodlibet.it.

- https://acrl.ala.org/ess/conferences/past-conferences/wess-conferences/past-wess-conference-programs.

- https://acrl.libguides.com/ess?b=g&d=a&group_id=14988.

- https://www.entrevues.org/lesalon.

- https://www.salondulivreafricaindeparis.com.

- https://www.crl.edu/programs/seemp.

- https://slowbooks.it.

- https://www.spdbooks.org.

- http://www.la-semyr.es.

- https://www.kulturradet.se/en/swedishliterature/publishers.

- https://www.nb.admin.ch/snl/en/home/research/bibliographies/swiss-book.html.

- http://swips.ch.

- https://www.forlaggare.se.

- https://traficantes.net.

- https://uzinefanzine.blogspot.com

- https://vzu.nl/de-vereniging.

- https://vobow.be/home/wa.

About the Authors

Sebastian Hierl is the Drue Heinz Librarian at the American Academy in Rome (AAR). He holds an MA and PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of South Carolina, and an MLIS from the University of Texas at Austin. Prior to the AAR, he held responsibility for Harvard College Library’s Western European collections and served as Bibliographer for English and Romance Languages and Literatures at the University of Chicago. Hierl started his library career as a Fellow and Collection Manager for the Humanities and Social Sciences at the North Carolina State University Libraries.

Claude H. Potts is the Librarian for Romance Language Collections at the University of California, Berkeley. From 2003–2007, he worked as the Latin American & Iberian Studies Librarian at Arizona State University Libraries in Tempe. He holds an MLIS and an MA in Comparative Literature from UCLA, where he also worked as the Director of Digital Initiatives for the Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. He has lived in France, Spain, Mexico, and Brazil, where he interned at the Library of Congress’ Field Office in Rio de Janeiro.