12 The Key Capacities Needed to Develop Change Agents

“You must unite behind the science. You must take action. You must do the impossible. Because giving up can never ever be an option.”— Greta Thunberg

This book charges higher education administrators, faculty, and students with an immense task. We are charged with responsibilities that are great and that require rising to the challenge of some serious calls to action such as transforming programmatic practices, transforming curriculum, transforming academia, and transforming ourselves. A willingness to rise to these challenges is a vital step toward not only developing change agents but addressing rapidly changing, large-scale sustainability problems. In short, a revolution is needed to address the gap between knowledge and action. In this concluding chapter, key strategies to revolutionize the way administrators and faculty train, support, develop, and reward students, faculty, and staff to ensure that the next generation of change agents are equipped to be proactive on the frontlines of climate and social change are outlined.

Rethinking Programming and Practices

Throughout this book, strategies for developing change agents, whether through programs, practices, or otherwise, are presented as frameworks for action for practitioners. These strategies and frameworks are, therefore, vital to transformative practices that build competencies for developing graduate student change agents and future leaders. Instead of a catalog of skills or topics, the emphasis of this book is built upon the premise that administrators and faculty must utilize diverse strengths, opportunities, and experiences within our multiple roles and positions to transform graduate sustainability leadership education. To do this, we must examine the status quo in every sustainability graduate education space we engage in. This may include rethinking what education looks like both programmatically and in practice. More importantly, we must recognize that there will never be a point where this reflexive process is complete. As new societal, environmental, and sustainability challenges arise, leadership is required and training for the next generations of leaders will need to continually evolve. The enterprise of pulling together this edited volume has already illustrated that there are just as many extremely diverse experiences aimed at addressing challenges and outcomes as there are extremely diverse challenges and outcomes. It is an asset that no two programs are the same. Instead of encouraging conformity, experimentation and providing space for the exchange of information to learn from one another should be encouraged.

It is only recently that the academy shifted away from the disciplinary silos that dominated the 20th century. At most universities, this shift has been limited to particular areas of inquiry, such as sustainability. Likewise, graduate education has typically focused on training the next generation of faculty who are siloed away from the public, only occasionally providing scientific insight that may be useful to the public if communicating with them at all. In order to conduct relevant scientific studies and incorporate a variety of knowledge (such as indigenous, local, and non-academic), academics need development in areas like leadership training, soft skills, respect for diverse understanding, and more. Because sustainability challenges require engagement with varied publics and local and global communities, both scientific studies and potential conclusions need to be tailored to the respective audiences by transforming the education enterprise at-large.

Transformative Training for Change Agents

If administrators and faculty want to develop change agents, they must provide transformational training. All of us, both individually and collectively, have a role in this transformation. This transformation cannot occur simply by changing the content; the entire enterprise must be transformed. In addition to thinking beyond the classroom, traditional programmatic practices can evolve by interweaving learning and experience for an intentional and seamless development of transdisciplinary competencies among future sustainability leaders and change agents. A shift in identity must be cultivated through real-world experience and engagement. Experiential learning provides the capacity for tangible and practical action development that translates into real change. However, planning, practice, and impact are mitigated by the fact that real and meaningful change takes time. By taking the necessary time needed to develop transformative change agents, the investment promises to yield a tremendous return, especially given the problems that challenge the world both now and in the future.

Traditional perspectives need to be questioned in order for traditional hierarchies to be transformed. While the importance of developing critical thinkers through education may never have ceased to have value for the academic landscape, when contextualized against the problems faced by sustainability leaders, there is a palpable urgency to ensure thoughtful solutions are intentionally carried into practice. This step from theory to practice, from inaction to impact, from problem to solution, requires that students, instructors, practitioners, and beyond re-evaluate hierarchies that stymie the collaborative possibilities excluded by an aging hierarchical structure that prioritizes ‘publish or perish’ competition or that enforces any boundaries that hinder unforeseen partnerships. The idea that a graduate education serves the purpose of reproducing faculty, as noted by Hellmann and Gerber (2019), does not allow a space for pedagogical innovation to flourish in the manner that this book deems necessary. What could transforming academia look like? Global problems require global solutions, so what better way to challenge traditional hierarchies and perspectives than to leverage a global network toward transdisciplinarity and supporting innovation, co-design, co-development, and multi-modal and faceted programming. Networks provide an opportunity to harness the tension between global and local communities by marrying information exchange, co-learning with other entities, and tailoring lessons for particular individuals and entities.

To advance this agenda, all of us must embrace the role of a change agent. In this concluding chapter, we explore 1) what it takes to be a change agent, 2) three key strategies that can be used to transform graduate training and the larger university enterprise, 3) future directions required to advance this agenda, and, based upon the rich empirical work in this volume, 4) guiding questions designed to inspire concrete action for developing change agents at your program or institution. We caution readers about the tendency to replicate success without careful self-reflection. Each place, program, and person have unique strengths that will not be fully utilized if a formulaic approach is taken to develop and support change agents.

What Does it Take to be a Change Agent?

Let us begin by understanding what needs to change. The sustainability “tent” is quite large but with emerging programs, degrees, and interdisciplines, there is danger that critical disciplines deemed outside of sustainability, such as the health and medical fields, will be excluded (Demorest & Potter, 2019). Instead of falling into the gatekeeping role that is all too common within academia or, conversely, arguing that everything is about sustainability, we argue that more attention should be paid to expanding the domain for interdisciplinary scholarship or, more importantly, transdisciplinary scholarship, where the bounds are training, and research spaces set within relevant communities. If we are truly going to develop agents of change, we must recognize that domains of needed change are not static and will require novel collaborations both inside and outside of the academy. This might require changes to, for example, what supports a case for tenure, but, more fundamentally, our students must be equipped and trained to work in these domains, develop new partnerships with people with very different ways of thinking, and work to collectively affect and scale change.

It is our premise that we can change ourselves, the planet, and our future through our practices, our investments in leaders, and our willingness to try things that are experimental, intentional, meaningful, and focused on solving the wicked problems we face. Graduate education in sustainability confronts two critical challenges. First, it must address problems that are embedded in increasingly complex and rapidly changing social, technological, and economic systems (Clayton & Radcliffe, 2018; Steffen et al., 2018). To meet this challenge, education must prepare future researchers to work across disciplines; build collaborative teams; integrate research from the sciences, engineering, social sciences, and humanities; engage with external stakeholders effectively, and co-create solutions with communities (Miller, 2010).

The second challenge is diversity. To date, a failure to recruit and train a diverse community of scholars that represents the larger society has undermined our ability to address deepening social, economic, hegemonic, and political inequalities (Hackl, 2018; Temper, Walter, Rodriguez, Kothari, & Turhan, 2018) and has decreased the academic enterprise’s responsiveness to the many pressing problems in poor and disenfranchised communities (Cozzens & Thakur, 2014). To effectively change our world, we must build the collective capacity to engage in transdisciplinary and community- and policy-embedded team science and meaningfully develop and support diverse communities of scholars and practitioners.

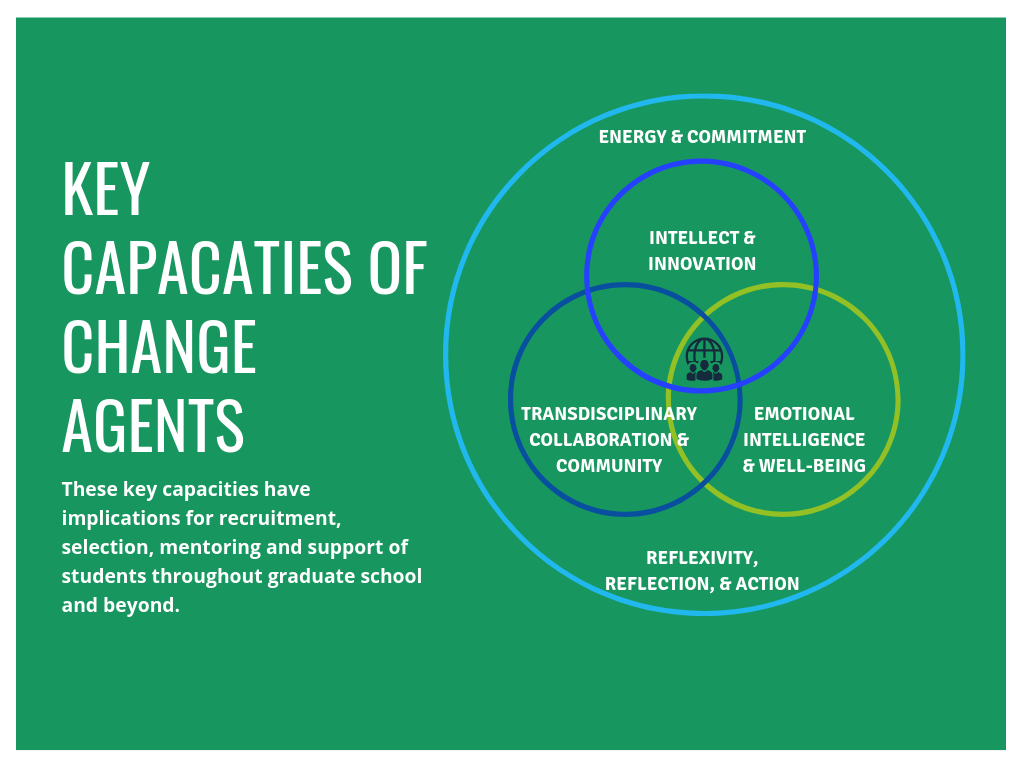

There are numerous lists of competencies (Lozano, Barreiro-Gen, Lozano, & Sammalisto, 2019; Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, 2011) used to develop sustainability graduate education programs, but a fundamental transformation of higher education that goes beyond competency is required (Gosselin et al., 2016; Vincent & Mulkey, 2015). We embolden the entire higher education enterprise to become change agents in order to deal with today’s sustainability challenges at multiple levels of agency: as individuals, communities, organizations, networks, and systems. With that in mind, we identify five critical change agent capacities that embolden the transformative aspects of developing change agents: transdisciplinary collaboration and community; intellect and innovation; emotional intelligence and well-being; energy and commitment; and reflexivity, reflection, and action (see Figure 1).

Transdisciplinary Collaboration & Community

Prior chapters recognize that, to address sustainability challenges, there must be a focus on both transdisciplinary science (Holden, Cockburn, Shackleton, & Rosenberg, 2019) and team science (John, Harsh, & Kennedy, 2019). Team research of complex, transdisciplinary problems faces challenges that are just as much sociological as technical (Anbar, Till, & Hannah, 2016) and soft skills are required to resolve them. Recent research hints at the importance of cultural identity over science literacy in basic information handling and risk analyses on culturally-loaded topics like climate change highlight the depth of this challenge (e.g., Drummond & Fischhoff, 2017; Kahan, 2012). Simply conveying the technical substance does not lead to correct and effective comprehension of a given topic. Learning how to effectively communicate is critical to conducting team science, advancing the co-production of transdisciplinary science with diverse publics, and informing critical policy questions. Effective communication is also critical for both conducting innovative interdisciplinary research and engaging diverse audiences. Communication without engaging with these diverse audiences and communities is ethically problematic both in terms of efficacy of interventions and in that it lacks incorporation of relevant local knowledge. For these reasons, knowledge co-production has emerged as one of the most significant new tools for global environmental change research (Miller & Wyborn, 2018). Communication across disciplines (Holden et al., 2019) is essential to impacting real world problems, but without embedding research within communities or policymaking (Holden et al., 2019; John et al., 2019) scientists may miss the most critical questions and much-needed solutions. Furthermore, effective communication is not simply about learning how to produce or translate science but also the soft skills needed to build trust with communities, publics, and teams (see John et al., 2019).

Sustainability decision-making occurs at many levels and in overlapping jurisdictions such as individual households, companies, local municipalities, utilities, states, and federal agencies. Change agents need to navigate these varied policymaking domains. Anticipatory and strategic governance and decision-making strategies are all key for participants in decision-making and for researchers seeking effective research interventions (Wiek et al., 2011). For example, the concept of anticipatory governance is becoming an increasingly valuable tool in a variety of socio-ecological systems and sustainability work (Armitage et al., 2009; Bates & St. Pierre, 2018; Wiek, Ness, Schweizer-Ries, Brand, & Farioli, 2012). In line with navigating those domains, chapters from this book highlight the nexus spaces between the university and the critical roles of developing capacity to communicate with policymakers (Posner, 2019) and the public (Weller, Wall, & Barron, 2019). In general, change agency in academic institutions is further catalyzed by involvement in institutional initiatives, whether by the top-level leadership driving them or by having all stakeholders seated at the table, where institution-wide collaboration is made possible.

Promising practice. An example of transdisciplinary collaboration and community is the Participatory Field Modeling School, which provides a 3-day training for graduate students, faculty, community members, and policymakers to engage in co-creating solutions to complex problems with members of the Detroit and Flint, Michigan communities. This is one example of how participatory-based modeling is being used by Eastside Community Network, the city of Detroit, and Michigan State University (see Figure 2). This community organization purchased abandoned lots and transformed them into a rainscape (which helps with the increasing flooding in the area) and an outdoor learning lab. Through this revitalized space, residents have access to both job training and education while, at the same time, a beautiful solution that works towards climate resilience has been created.

In Detroit, there are 70,000 abandoned properties and there has been a push to revitalize the land through farming. But, if you speak to many older black residents who remember the Great Migration from the South (1916-1970), the last thing they want to do is farm. For many, farming represents a trauma-filled life in the South that they escaped. This human perspective is something a “well-intentioned” academic could easily miss. Without knowing the history of an area and, more importantly, not knowing how the people that live there are impacted by policies and solutions created in the ivory tower, effective change cannot occur. https://modeling.engage.msu.edu/

Intellect & Innovation

Harnessing the intellectual and innovative talents of the gifted has been a driving force for leadership development throughout history. Approximately 2000 years ago, Plato devised an educational program for the most gifted to be future leaders known as ‘men of gold.’ These men were separated from their peers of lesser intellect who were known as ‘silver,’ ‘iron,’ or ‘brass’ men (Freeman, 1980). The role of higher education in developing the infant nation’s leadership was on the mind of the founding fathers and was most clearly articulated through Thomas Jefferson’s vision when he developed the University of Virginia. Jefferson believed that higher education should create leading scientists, researchers, and leaders (Brubacher & Rudy, 1997). Today’s sustainability change agents need strong intellectual and innovative acumen to navigate the vast complexity of the entangled issues that are endemic to sustainability.

To address these challenges, graduate education should provide students with skills that facilitate collaborative, use-inspired research that contributes to effective community solutions to complex systems problems. Sustainability challenges require novel research frameworks and approaches that are: (1) cross-disciplinary, advancing with human-ecological-technical systems (Anderies, Janssen, & Ostrom, 2004); (2) cross-scale, addressing the linkages between local, regional, and global structures and dynamics (Scholes, Reyers, Biggs, Spierenburg, & Duriappah, 2013); (3) cross-system, interrogating the dynamic interactions across interconnected systems that result in the propagation of vulnerabilities and resiliencies across the interconnected systems (Berardy & Chester, 2017); and (4) cross-temporal, addressing the divergent timing cycles that characterize many sustainability challenges (Holdschlag & Ratter, 2016). In summary, sustainability scholarship requires deft capabilities both to model systems and to anticipate and strategically develop innovative interventions or policies, such as resilient infrastructure systems.

Understanding the causes and consequences of long-term interactions between human and natural forces is vital to addressing questions of sustainability. However, the complex nature of both social and ecological systems and the even more complex interactions between human and natural systems severely limit our capacity to intuit the causes of change and the consequences of human action. Reductionist analytical approaches designed to isolate linear cause and effect relationships are therefore often ineffective (Dawson, Rounsevell, Kluvánková-Oravská, Chobotová, & Stirling, 2010). These issues of non-linear causality and long time-scales have made quantitative, process-based modeling especially important for scientific study (Dearing et al., 2014). Model-based science provides tools for the exploration and analysis of the multi-dimensional, non-linear, and, often, counter-intuitive interactions between social and biophysical processes that drive modern earth systems. Modeling environments can be used as virtual laboratories to study how system dynamics can play out over long time spans (van der Leeuw, 2004).

Promising practice. The Acara Challenge at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment provides interdisciplinary and cross-sector coaching opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students that includes impact labs, courses, and study abroad experiences in which students engage in solving real-world problems. Every spring a competition is held that awards students up to $5000 in funding for their projects. http://environment.umn.edu/leadership/acara/

Emotional Intelligence & Well-Being

Beginning in the ecological literature, and more recently adopted by social-ecological science and sustainability, resilience is an important concept that recognizes the relationship between adaptation and transformation and stability of systems. Expanding the notion of resilience to also include the individual, we should encourage individuals to transform when opportunities arise as well as develop an adaptive capacity to navigate the difficult (and often novel) challenges in the sustainability space. To encourage this, we argue that we must focus our attention on the critical issues of psychosocial support within the academy and our communities of practice and recognize the opportunities for transformation and change during periods of crisis (Kremers & Hecht, 2019). Vulnerabilities must be recognized in systems, societies, groups, and individuals while not isolating them from the structural interconnections within the broader system within which we live and work (Cole, 2016). There are numerous opportunities to engage with vulnerability, such as through self-reflection, but major events and disasters provide opportunities to reassess practices and build resilience. Instead of only seeing loss with disaster, we must recognize the opportunities that are present.

There is a different mindset required to harness vulnerability (Brown, 2018). Developing this mindset requires exposure to new ways of thinking about change and resilience. Coupling theoretical training with experiential learning, especially the coproduction of knowledge with diverse communities, grounds this abstract idea in the real world. Vulnerability in one individual, place, or community does not mean universal weakness; building teams, networks, and collaborations between people, cities, and societies enables the larger collectives to leverage diversity via the uniqueness of the components. Building, designing, and responding to change in new ways will require innovation that is based on creativity and imagination that is enhanced through diversity, coproduction, and encouraging students to embrace novel insights and ways of knowing. With this focus on vulnerability, we must also provide diverse change agents with the necessary psychosocial support. We must support diverse individuals and communities at our university and beyond.

Promising practice. In the Boreas Leadership Program at the University of Minnesota, all of the students take the EQi, an emotional intelligence inventory that flags students who may need additional mental health support during graduate school and also points out the students who have the greatest leadership potential. This tool, and other assessments like it, provide students opportunities for enhanced self-awareness, other-awareness, and transformational coaching. http://environment.umn.edu/leadership/boreas/

Energy & Commitment

Mustering and harnessing the courage, imagination, and discipline needed to tackle the wicked sustainability challenges we face requires immense energy and commitment. Working with policy actors and communities, dealing with loss and uncertainty, working across cultures, and negotiating conflicting priorities are time intensive, cognitively intensive, and emotionally intensive tasks. Change agents will face a multitude of challenges to which there is no one roadmap or formula to follow. Commitment and the resulting energy from that deep sense of commitment are key to navigating the issues that will naturally arise. Co-creating, sustaining change, and constantly recalibrating to the call of the future as situations shift and evolve are necessary in the dynamic world we seek to protect.

Promising practice. Arizona State University (ASU) is making the commitment and investing the energy needed to transform into a New American University (n.d.). Motivated by ASU’s charter the university is, “measured not by whom we exclude, but rather by whom we include and how they succeed.” Commitment to the charter is demonstrated through faculty hiring and tenure decisions, the creation of new programs, and allocating scarce university resources to individuals who are collectively advancing eight design aspirations: leverage our place, enable student success, transform society, fuse intellectual disciplines, value entrepreneurship, be socially embedded, conduct use-inspired research, and engage globally. The commitment and energy of the entire university, including faculty and students, is transforming the university and motivating it to shift toward a change agent mentality. https://newamericanuniversity.asu.edu

Reflexivity, Reflection, & Action

There are no panaceas for sustainability governance questions (Ostrom, Janssen, & Anderies, 2007). We must tailor our science, policy recognitions, universities, programs, and ourselves to the particular strengths and challenges we face. Building upon the idea of adaptive management, especially adaptive co-management, we must reflexively and continuously monitor change (Waghid, 2002). We must be willing to ask tough questions of ourselves and each other in order to improve (Viegas et al., 2016). As each of us determines how we might be a better change agent, we must first assess where own strengths, experiences, and opportunities lie. Instead of constantly looking over our shoulders at the neighboring students, faculty members, universities, or communities, we must instead focus on ourselves and assess who we can be given who we are. Part of this exercise in reflexivity should focus on building diverse teams and networks in order to leverage our diversity (Wilsey et al., 2019). Higher education has been recognized as a means to foster meaningful change in societies (Stephens, Hernandez, Román, Graham, & Scholz, 2008); likewise, with the emergence of sustainability as an academic discipline, a body of work has focused on how higher education can be transformed to advance the new discipline (Gosselin et al., 2016). In our view, there is a gap in the literature leading to minimal exploration of the reflexive processes whereby higher education and society are transformed by the actions of the public, students, faculty, universities, and networks and associations of scholars and universities.

Promising practice. In 2016, faculty and academic professionals from across ASU came together to critically question why diversity in the faculty was lacking; this gap was especially worrying given the university’s commitment to transdisciplinary research (which necessitates diverse ways of thinking) and the increasingly diverse undergraduate body. The university’s self-reflective process, which consisted of a series of workshops held by representatives from across ASU’s four campuses, led to an understanding that along the entire “pipeline,” from undergraduate students, graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows to junior and senior faculty members, the mentoring structures in place were not adequate for supporting intersectional diversity that recognized gender, race, ethnicity, foreign-born status, sexual orientation, disability, rank, and discipline. A result of this reflexive process was a National Science Foundation ADVANCE grant used to develop the resources needed to support underrepresented students and faculty through their entire academic life course. These resources include The 7 Minute Mentor professional development videos that provide individual leaders’ “stories of reflection, lessons learned, and what drives their passion for advocating for equity for all” (Arizona State University, 2018). The Arizona State University ADVANCE Program (n.d.) has led to the creation of external and internal structures and processes to continuously examine whether ASU is meeting its equity goals. https://advance.asu.edu/

Key Strategies

How do we develop these five critical change agent capacities? Throughout this volume, scholars have provided a rich set of individual, programmatic, university, and inter-university network approaches. Below we synthesize these into three key strategies that enable the development of change agents while also recognizing that there are numerous strategies for developing change agents.

Key Strategy I: Getting out of the Ivory Tower and into Communities Through Stakeholder-engaged Teams

Institutional change and decision-making is possible from within institutions, whether through senior leadership positions, a seat at the table, or passionate individuals at any level. But change agency should not be limited to internal change or patiently waiting for momentum toward transformation to build from the outside in, whether through government legislation, donor funding, or social pressures. The effort toward developing a capacity for effective, impactful change must transcend the academic milieu. Whether by establishing connections with and within communities through community brokers, leveraging community engagement initiatives, or other connections, as Holden et al. (2019) emphasize, universities should consider alternative models to graduate training beyond the single, scholarly dissertation. One way to achieve this would be by adjusting existing timelines and benchmarks, like time to degree, to support the often long length of time that is required to meaningfully engage communities in transdisciplinary science.

Furthermore, the complexity of sustainability problems requires extraordinary collaboration that transcends traditional disciplinary divisions. As authors Dale and Leighton (2019) illustrate, sustainable community development can be tackled not only in a theoretical way but also by literally taking the classroom to the city. In order to fully explore a robust amount of possible resolutions, being immersed in the context where problems emerge or subsist, in this case the city, creates space for sustainable community development through immersion in the city. This also involves working closely with city staff to identify problems that need to be solved, acknowledging that relationship-building is a key to sustainable community development. By creating such a space, collaboration can be cultivated beyond the theoretical, problems can be addressed, and knowledge becomes action.

Key Strategy II: Building Trust Through Cohorts, Networks, and Genuine Collaboration

Not all academic departments encourage collaborative work in the same way. This is why cohort-building and engagement in networks is key. For example, leadership and sustainability problem-solving can come together in a pivotal way that allows public policy to shape debates and tackle issues. Hence, capacity building that connects science and policy has the chance to support action in impactful ways and help develop leaders that are able to work across both science and policy while using skills that support sustainability. This is the sustainability leadership model of development that is addressed by John et al. (2019), where some key points of educational program design include creating an environment of trust, striving for diversity among program participants, and establishing an alumni network.

Establishing trust is not easy. Trust has to be earned which takes time. For programs to successfully champion this strategy for developing change agency, they should consider following the model addressed by Wilsey et al. (2019), the Master in Development Program (MDP). The MDP curriculum has been adopted and adapted by more than 40 universities. Hallmarks of the program have been adaptations to local needs, values, and university strengths such as in-depth training in indigenous worldviews at the University of Winnipeg, curriculum extension through a joint law and MDP program at the University of Florida, and a novel pedagogical innovation of a year-long Development Lab at Columbia University. All of these MDPs have a required field practicum that provides necessary training in a consultancy model because most developing practitioners engage in it throughout their career. Therefore, graduate programs that adapt to local conditions and connect to other universities’ experiences and innovations through a global network allow strategic evolution that addresses real world needs to occur.

Key Strategy III: Transforming Support & Reward Structures to Elevate Innovations in Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Approaches

A critical aspect to furthering sustainability science and education is dismantling or disrupting organizational hierarchies that limit or restrict innovations that are driven by faculty, students, or other sources. As Carlson (2019) describes, graduate students come to the classroom with a more nuanced understanding of complexity and sustainability than some academics. These students often challenge disciplinary boundaries that restrict their ability to conduct thoughtful sustainability science and apply it to real-world problems. Hence, Carlson (2019) argues that students are agents, not simply recipients of existing knowledge, and by harnessing their insights and recognizing their role in motivating individual faculty, students co-develop graduate education models, challenge existing structures, and influence faculty perspectives and attitudes overall.

Additionally, Weller, Wall, and Baron (2019) discuss how a cohort model provides, among a variety of skills development opportunities, essential training in areas, like communication, to help cultivate the capacity for scientists to share research findings beyond the establishment – a facet of sustainability leadership requiring an incentive beyond the traditional academic milieu. Although rewarded in the academic context, communicating exclusively with peer experts through publications or conference presentations fails to net the impacts that we argue are required to adequately address sustainability challenges. Similarly, written work remains more valued than oral presentation contributions. Luckily, the capacity to communicate across audiences is being increasingly recognized as essential to graduate student training and education through opportunities like the Three Minute Thesis, a global competition founded by the University of Queensland in 2008.

Transdisciplinary collaboration also means that different types of partnerships will need to be supported. This is why, in highlighting the center-focused approach taken by the Mitchell Center at the University of Maine, Bieluch, Hart, McGreavy, Silka, & Strong (2019) present a case for partnerships inside and outside academia that support graduate students with leadership development so they can act as change agents on complex problems in a multifaceted world. Altogether, these partnerships and collaborations leverage various factors to enhance professional success for both faculty and students but requires that the capacity to communicate across audiences becomes an integral part of the graduate education experience.

In summary, we recognize that there are numerous strategies for developing sustainability change agents. We concede that this volume is not exhaustive, so the question to our audience is: What are other strategies? We must not only look toward future possibilities of alignment with scholarship and practice but also work toward it, which is why we optimistically conclude with possible future directions.

Future Directions

This collective work identifies a path forward for developing change agents that includes a number of areas that could benefit from increased scholarship and experimentation. Specifically, there needs to be significant development in the literature on diversity and vulnerability. Diversity and inclusion are both challenges and opportunities that must be addressed at multiple levels and in multiple dimensions. Simply put, not all people, places, or universities are the same. Instead of attempting a cookie-cutter approach to graduate education for sustainability, we must instead reflect upon the diversity of strengths and weaknesses. Without embracing diversity on teams, across programs and universities, and through community-university collaborations, we are more vulnerable and less knowledgeable. Without using reflexivity to improve, adapt, and build diverse, transdisciplinary teams we will fail in our quest to tackle sustainability issues. In this section, we unpack the frontiers of diversity and vulnerability necessary to develop change agents for leadership in sustainability.

Partially an artifact of the original ANGLES Network, which originated with American and Canadian universities, and also reflective of western-dominated sustainability scholarship (Nagendra, Bai, Brondizio, & Lwasa, 2018), this volume lacks the necessary international diversity to tackle sustainability planet-wide. Because of this, we urge readers to view this volume as a starting point, a call for reflexivity, renewed energy, and commitment to transforming higher education. Even as we engage in more North-South transdisciplinary scholarship, we must be aware of the power differences and historic lack of diversity and colonialism associated with the scientific enterprise (Schmidt & Neuburger, 2017). More voices are needed to help advance this agenda and embolden change agents throughout the world.

In order to recruit, retain, mentor, and develop diverse students and scholars, we must look reflexively and closely at ourselves. Universities have always faced a diversity challenge (Patton, 2016). Typically, diversity is viewed as a long-term problem that needs, and will attain, an eventual solution. However, this “slow” approach does not match the seriousness and immediacy of the diversity crisis nor does it provide the means to attempt to deal with these challenges head-on. Women and minorities continue to face systematic, silent discrimination and harassment as well as direct and severe attacks both online and in-person. The diversity “issue” is often framed as a lack of access or inequality for particular students and populations, but this perceived failure also exacerbates inequalities (Nagendra et al., 2018) and engineers systems that distribute unequal risks and vulnerabilities across groups (Chatterjee & Turnovsky, 2012). Furthermore, recent scholarship has demonstrated that access to higher education without adequate support is insufficient when it comes to retaining and developing diverse undergraduate student bodies (Jack, 2019) and that the key to support is inclusion and embracing diverse identities (Puritty et al., 2017). As change agents, we must build the programmatic and community scaffolding within and across universities to support individuals and historically underrepresented groups, dismantle the impacts of structural racism and white privilege on our campuses, and aid in efforts to tear down these insidious structures across the globe.

How to Get Started

Every person reading this book (students, faculty, academic professionals, administrators, or otherwise) can become a change agent. Working collectively at multiple levels and scales with diverse perspectives and experiences we can transform institutions in order to solve global challenges. All too often, the process of conceptualizing problems and developing high-level strategies is disconnected from concrete steps, a path forward. We tasked our authors to focus their attention on specific elements of their training programs and experiences and then used those elements to identify the critical capacities and key strategies listed below. Depending on your role and interests, as well as programmatic and university contexts, you can pick and choose from the capacities and strategies listed below to begin to transform the academy.

Challenging the dominant pedagogical models is not easy, but there is agency with individual students (Carlson, 2019; Holden et al., 2019; Kremers & Hecht, 2019), faculty (Dale & Leighton, 2019; Demorest & Potter, 2019; John et al., 2019), programs (Bielich et al., 2019; Weller et al., 2019), and universities (Carlson, 2019). Our authors also often point out the strength that comes from cohorts (Weller et al., 2019), faculty teams (Dale & Leighton, 2019), program networks (Wilsey et al., 2019), and higher education networks (Carlson, 2019). What these various perspectives point out is that collectively we can make significant progress if we work together. Motivating groups to tackle major issues and affect change is not easy. Doing so requires sophisticated leadership skills that include the ability to understand incentives and constraints of decision-makers and targeted training to build capacity to affect change (Gordon et al., 2019). In addition to multifaceted training in communication, students, faculty, and publics need to learn how to increase efforts to help transform research projects, outreach, programs, and communities. Although rich literature on team collaboration (e.g., McGreavy et al., 2015) with diverse stakeholders (e.g., Finio, Lung-Amam, Knaap, Dawkins, & Knaap, 2019) and decision-makers (e.g., Schoon & Cox, 2018; York & Schoon, 2011) exists, much of the “art” of collaboration requires experiential learning in order to understand how to codevelop research questions with publics, work with diverse sets of stakeholders, and engage the public with science in a useful way (Brundiers & Wiek, 2017). Many sustainability challenges require society to scale solutions and governance without losing site of diversity and local context (Singh, Keitsch, & Shrestha, 2019; Sheridan, Satterwhite & McIntyre Miller, 2019). Likewise, changing higher education to meet these needs also requires establishing and building new networks. One of the first steps that change agents can take is transforming the curriculum to meet these immediate needs.

Looking Forward

As we look to the future, we must first understand where we are now. We encourage every program, department, and college to utilize a systems thinking perspective to examine the barriers to developing change agents. In what ways, during recruitment, selection, retention, and post-graduation, could you better support and challenge your students and alumni to be agents of change? How are you currently failing? We must take an honest, hard look at ourselves, our programs, and our institutions with great care. If our charge is, “How can we help challenge and support our students to flourish so that they can do seemingly impossible things?”, what do we need to do differently?

Throughout this book, we have explored various changes that can be made to the competencies and associated learning outcomes needed to address the wicked sustainability challenges we face. In addition, we explored how there is a tendency to externally look at the scale of these grand challenges we face rather than acting on the interior landscape challenges faced in our institutions, departments, labs, teams, and indeed, ourselves. To develop change agents we must radically reshape the academy to create cultures that cultivate and nurture risk taking and resiliency and that honor varied paths. Cultural change is not for the faint of heart, but radical change is necessary to create academic cultures which support, develop, retain and promote change agents. Our collective mindset needs to shift from, “How will we do this?”, which tends to provoke conversations that swirl in stagnation in academia to actively prototyping our way forward with a willingness to take risks and continually learn from our mistakes and successes along the way. This is our generation’s version of the moon landing. Together we can (and must) go far.

10 Key Questions to Examine the Health of Your Academic Unit and Develop Change Agents

- What opportunities exist for your students to engage in stakeholder-engaged research and scholarship?

- Do you highlight faculty and/or other role models (including successful alumni) who have made real-world impacts?

- How does your program encourage students, staff, and faculty to take part in risk-taking and prototyping?

- What are successful transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary initiatives that have been supported by your academic unit?

- How do you support the mental health and well-being of your graduate students and faculty? How do you create a culture of resilience?

- How do you nurture the next generation of diverse students and faculty? Are there support structures in place that help individuals deal with biases and navigate unequal access? What are the efforts being made to dismantle structures that perpetuate inequality both on campus and beyond?

- How are you supporting champions of change and developing your change agents? Do you support and empower professional staff and academic faculty in your programs to affect change?

- How reflexive and committed are your university, programs, faculty, and students to continuous transformation?

- What are the unique ways in which your unit can train graduate students to be sustainability leaders today and tomorrow? Are there supports in place to build capacity for both academic and non-academic non-traditional roles?

- If the traditional post-secondary academic context is undergoing a radical transformation, how can students, staff, and administrators remain ahead of the curve and proactive in solving wicked problems?

References

Anbar, A. D., Till, C. B., & Hannah, M. A. (2016). Bridge the planetary divide. Nature News, 539(7627), 25.

Anderies, J., Janssen, M., & Ostrom, E. (2004). A framework to analyze the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecology and Society, 9(1). Retrieved from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art18/

Arizona State University. (2018). 7 Minute Mentor. Retrieved from: https://advance.asu.edu/7-minute-mentor

Arizona State University. (n.d.). Arizona State University ADVANCE Program. Retrieved from: https://advance.asu.edu/

Arizona State University. (n.d.) New American University. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://newamericanuniversity.asu.edu

Armitage, D. R., Plummer, R., Berkes, F., Arthur, R. I., Charles, A. T., Davidson-Hunt, I. J., … McConney, P. (2009). Adaptive co‐management for social–ecological complexity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(2), 95-102.

Bates, S., & Saint-Pierre, P. (2018). Adaptive policy framework through the lens of the viability theory: A theoretical contribution to sustainability in the Anthropocene Era. Ecological Economics, 145, 244-262.

Berardy, A., & Chester, M. V. (2017). Climate change vulnerability in the food, energy, and water nexus: Concerns for agricultural production in Arizona and its urban export supply. Environmental Research Letters, 12(3), 035004.

Bieluch, K., Hart, D., McGreavy, B., Silka, L., & Strong, A. (2019). Empowering sustainability leaders: Variations on a learning-by-doing theme. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/empowering-sustainability-leaders/

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. New York, NY: Random House.

Brubacher, J. S., & Rudy, W. (1997). Higher education in transition: A history of American colleges and universities. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. (2017). Beyond interpersonal competence: Teaching and learning professional skills in sustainability. Education Sciences, 7(1), 39.

Carlson, C. (2019). Students as drivers of change: Advancing sustainability science, confronting society’s grand challenges. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/students-as-drivers-of-change/

Chatterjee, S., & Turnovsky, S. J. (2012). Infrastructure and inequality. European Economic Review, 56(8), 1730-1745.

Clayton, T., & Radcliffe, N. (2018). Sustainability: A systems approach. London: Routledge.

Cole, A. (2016). All of us are vulnerable, but some are more vulnerable than others: The political ambiguity of vulnerability studies, an ambivalent critique. Critical Horizons, 17(2), 260-277.

Cozzens, S., & Thakur, D. (Eds.). (2014). Innovation and inequality: Emerging technologies in an unequal world. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Dale, A. & Leighton, H. (2019). Where living and learning meet: Bringing the classroom into the city. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/where-living-and-learning-meet/

Dawson, T. P., Rounsevell, M. D., Kluvánková-Oravská, T., Chobotová, V., & Stirling, A. (2010). Dynamic properties of complex adaptive ecosystems: Implications for the sustainability of service provision. Biodiversity and Conservation, 19(10), 2843-2853.

Dearing, J. A., Wang, R., Zhang, K., Dyke, J. G., Haberl, H., Hossain, M. S., … & Carstensen, J. (2014). Safe and just operating spaces for regional social-ecological systems. Global Environmental Change, 28, 227-238.

Demorest, S. & Potter, T. (2019). Climate change and health: An interdisciplinary exemplar. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/climate-change-and-health/

Drummond, C., & Fischhoff, B. (2017). Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(36), 9587-9592.

Finio, N., Lung-Amam, W., Knaap, G. J., Dawkins, C., & Knaap, E. (2019). Metropolitan planning in a vacuum: Lessons on regional equity planning from Baltimore’s Sustainable Communities Initiative. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1-19. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1565822

Freeman, J. (1980). Gifted children: Their identification and development in a social context. Lancaster, UK: MTP Press Limited.

Gordon, I. J., Bawa, K., Bammer, G., Boone, C., Dunne, J., Hart, D., …Taylor, K. (2019). Forging future organizational leaders for sustainability science. Nature Sustainability, 2, 647–649.

Gosselin, D., Vincent, S., Boone, C., Danielson, A., Parnell, R., & Pennington, D. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: Negotiating boundaries: effective leadership of interdisciplinary environmental and sustainability programs. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 6(2), 268-274.

Hackl, A. (2018). Mobility equity in a globalized world: Reducing inequalities in the sustainable development agenda. World Development, 112, 150-162.

Hellmann, J. & Gerber, L. (2019). Challenges and opportunities for training agents of change in the Anthropocene. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/training-agents-of-change/

Holden, P., Cockburn, J., Shackleton, S., & Rosenberg, E. (2019). Supporting and developing competencies for transdisciplinary postgraduate research: A PhD scholar perspective. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/supporting-and-developing-competencies/

Holdschlag, A., & Ratter, B. M. (2016). Caribbean island states in a social-ecological panarchy? Complexity theory, adaptability and environmental knowledge systems. Anthropocene, 13, 80-93.

Jack, A. (2019). The privileged poor: How elite colleges are failing disadvantaged students. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

John, K., Harsh, M. R. & Kennedy, E. B. (2019). Science Outside the Lab (North): A science and public policy immersion program in Canada. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/science-outside-the-lab/

Kahan, D. (2012). Why we are poles apart on climate change. Nature News, 488(7411), 255.

Kremers, K. L. & Hecht, N. (2019). Transforming the emotional intelligence and mental health crisis in academia: Co-creating pathways for post-traumatic growth, resiliency, and leadership agency in graduate students and faculty. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/masters-of-development-practice/

Lozano, R., Barreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, F. J., & Sammalisto, K. (2019). Teaching sustainability in European higher education institutions: Assessing the connections between competences and pedagogical approaches. Sustainability, 11(6), 1602.

McGreavy, B., Lindenfeld, L., Bieluch, K. H., Silka, L., Leahy, J., & Zoellick, B. (2015). Communication and sustainability science teams as complex systems. Ecology and Society, 20(1). Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06644-200102

Michigan State University Innovations in Collaborative Modeling. (n.d.) Participatory Modeling Field School. Retrieved from: https://modeling.engage.msu.edu/

Miller, C. A. (2010). Policy challenges and university reform. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, 333, 334.

Miller, C. A., & Wyborn, C. (2018). Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environmental Science & Policy. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.016

Nagendra, H., Bai, X., Brondizio, E. S., & Lwasa, S. (2018). The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 341.

Ostrom, E., Janssen, M. A., & Anderies, J. M. (2007). Going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15176-15178.

Patton, L. D. (2016). Disrupting postsecondary prose: Toward a critical race theory of higher education. Urban Education, 51(3), 315-342.

Posner, S. (2019). Policy engagement for sustainability leaders. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/sustainability-leaders-policy/

Puritty, C., Strickland, L. R., Alia, E., Blonder, B., Klein, E., Kohl, M. T., … Gerber, L. R. (2017). Without inclusion, diversity initiatives may not be enough. Science, 357(6356), 1101-1102.

Schmidt, L., & Neuburger, M. (2017). Trapped between privileges and precariousness: Tracing transdisciplinary research in a postcolonial setting. Futures, 93, 54-67.

Scholes, R. J., Reyers, B., Biggs, R., Spierenburg, M. J., & Duriappah, A. (2013). Multi-scale and cross-scale assessments of social–ecological systems and their ecosystem services. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(1), 16-25.

Schoon, M., and Cox, M. (2018). Collaboration, adaptation, and scaling: Perspectives on environmental governance for sustainability. Sustainability, 679. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030679

Sheridan, K., Satterwhite, R., & McIntyre Miller, W. (2019). Embracing new leadership constructs: Graduate leadership education for a sustainable and peaceful future. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/embracing-new-leadership-constructs/

Stephens, J. C., Hernandez, M. E., Román, M., Graham, A. C., & Scholz, R. W. (2008). Higher education as a change agent for sustainability in different cultures and contexts. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(3), 317-338.

Singh, B., Keitsch, M. M., & Shrestha, M. (2019). Scaling up sustainability: Concepts and practices of the ecovillage approach. Sustainable Development, 27(2), 237-244.

Steffen, W., Rockström, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T. M., Folke, C., Liverman, D., … Donges, J. F. (2018). Trajectories of the Earth system in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(33), 8252-8259.

Temper, L., Walter, M., Rodriguez, I., Kothari, A., & Turhan, E. (2018). A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: Resistances, movements and alternatives. Sustainability Science, 13(3), 747-764.

University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment. (2016). Acara. Retrieved from: http://environment.umn.edu/leadership/acara/

University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment. (2016). Boreas Leadership program. Retrieved from: http://environment.umn.edu/leadership/boreas/

van der Leeuw, S. E. (2004). Why model? Cybernetics and Systems, 35(2-3), 117-128.

Viegas, C. V., Bond, A. J., Vaz, C. R., Borchardt, M., Pereira, G. M., Selig, P. M., & Varvakis, G. (2016). Critical attributes of sustainability in higher education: A categorisation from literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 126, 260-276.

Vincent, S., & Mulkey, S. (2015). Transforming US higher education to support sustainability science for a resilient future: The influence of institutional administrative organization. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 17(2), 341-363.

Waghid, Y. (2002). Knowledge production and higher education transformation in South Africa: Towards reflexivity in university teaching, research and community service. Higher Education, 43(4), 457-488.

Weller, A., Wall, D., & Barron, N. (2019). Building a successful leadership program. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/building-a-successful-leadership-program/

Wiek, A., Ness, B., Schweizer-Ries, P., Brand, F. S., & Farioli, F. (2012). From complex systems analysis to transformational change: A comparative appraisal of sustainability science projects. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 5-24.

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203-218.

Wilsey, D., Galloway, G., Scharffenberger, G., Reid, C., Brown, K., Miller, N., … Swatuk, L. (2019). The Master of Development Practice (MDP): Reflections on an adaptive and collaborative program strategy to develop integrative leaders in sustainable development. In K. L. Kremers, A. S. Liepins, & A. M. York (Eds.), Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved from: https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents/chapter/masters-of-development-practice/

York, A. M., & Schoon, M. L. (2011). Collective action on the western range: Coping with external and internal threats. International Journal of the Commons, 5(2), 388-409.