6 Supporting and Developing Competencies for Transdisciplinary Postgraduate Research: A PhD Scholar Perspective

Petra Holden; Jessica Cockburn; Sheona Shackleton; and Eureta Rosenberg

Jessica Cockburn, PhD, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa

Sheona Shackleton is Deputy Director of the African Climate and Development Initiative at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and an Honorary Professor with the Department of Environmental Science, Rhodes University, South Africa

Eureta Rosenberg is the Chair of Environment and Sustainability Education, and Director of the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University, South Africa

“S/he who wants to walk fast, walks alone; s/he who wants to walk far, walks with others” ~ African proverb

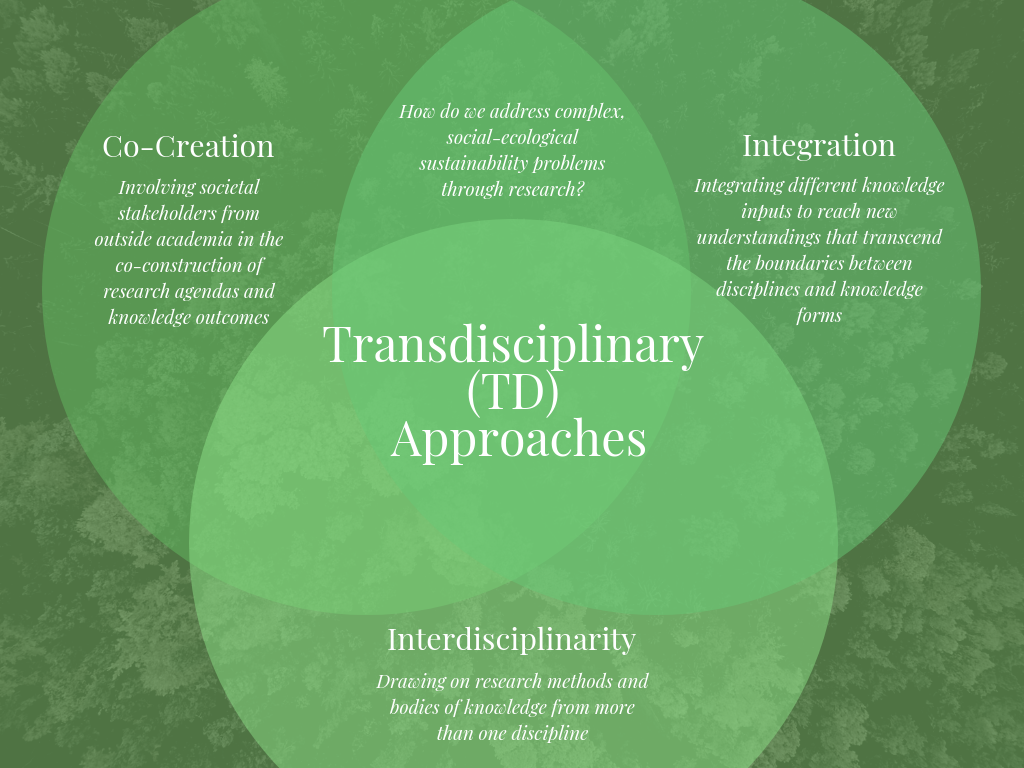

There is a growing interest in transdisciplinary (TD) approaches to sustainability research (Stock & Burton, 2011). While TD research has merit, it is also challenging, particularly in the context of postgraduate research for degree purposes at universities (van Breda, Musango, & Brent, 2016). In this chapter, two scholars (Cockburn and Holden), who took a TD approach in their Ph.D. studies at two universities in South Africa, stories are shared. Their co-authors are two faculty members who have taught and researched TD contexts. For this work, the ability to address complex, social-ecological sustainability problems through research was an important consideration when choosing TD approaches. But what is TD research? Different fields have different understandings and definitions (Stock & Burton, 2011). When engaging the literature with scholarly intentions, it was determined that three key features of TD research are related and equally important in TD research (Figure 1):

- Interdisciplinarity – drawing on research methods and bodies of knowledge from more than one discipline;

- Co-creation – involving societal stakeholders from outside academia in the co-construction of research agendas and knowledge outcomes; and

- Integration –integrating different knowledge inputs to reach new understandings that transcend the boundaries between disciplines and knowledge forms.

This three-part framing is used to reflect on the research experiences shared in this chapter and investigate how conducting TD research within doctoral studies has the potential to develop scholars as change agents and leaders for sustainability.

This chapter also reflects on the competencies that the two Ph.D. scholars found they needed to undertake TD research and that others in the literature believe could support work in TD contexts, inside and outside of academia.Furthermore, the chapter shares the institutional challenges the Ph.D. scholars experienced and reflects on what universities could do to better enable TD research as a scholarly undertaking that produces degree-earning change agents and as a transformative science that addresses complex sustainability challenges.

Transdisciplinary Research and Sustainability Competencies in Higher Education

Why are TD approaches to sustainability research increasingly popular? Much has been written about the need for the scientific community to produce knowledge that is of foundational value and can be immediately applied in addressing societal problems. In recent years, limitations that single, traditional disciplines have for addressing wicked problems like climate change, natural resource depletion, and managing landscapes sustainably for inclusive benefits have been recognized. This is a key reason for TD approaches, which are regarded as means of producing solution- and change-oriented knowledge (Hadorn et al., 2008; Lang et al., 2012).

While TD research creates a framework that enables the ability to conduct engaged sustainability research (Polk, 2014; van Breda & Swilling, 2018), it also poses challenges, particularly in doctoral research (Enengel et al., 2012; Mitchell, Cordell, & Fam, 2015; van Breda et al., 2016). Transdisciplinary research challenges described in the literature include the demands of disciplinary-based departments and examination requirements (Palmer, Fam, Smith, & Kent, 2018), inappropriate institutional research ethics requirements (Cockburn & Cundill, 2018), and failures to clearly define what knowledge types and outputs are recognized and incentivized (Park, 2006; Parker & Crona, 2012), leaving Yarime et al. (2012) and Dedeurwaerdere (2013) to conclude that existing academia institutional structures are not well-suited for TD research.

Despite the various TD research challenges, many scholars desire to conduct TD research. Actively and intentionally “doing TD” may be one of the best ways for scholars to develop the competencies needed to address complex sustainability challenges and become change agents. By competencies, we mean “a functionally linked complex of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable successful task performance and problem solving” (Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, 2011, p. 204). Wiek et al. (2011) reviewed a considerable body of emerging work on competencies needed in the sustainability sciences and Scharmer and Kaufer (2013) documented leadership competencies that change agents addressing complex problems need. Drawing on these authors’ work, Rosenberg, Lotz-Sisitka and Ramsarup (2018) and Rosenberg, Ramsarup, Gumede and Lotz-Sisitka (2016), highlighted three kinds of competencies that change agents tasked with driving sustainability transitions need: technical, relational, and transformative.

While there is a large body of literature that broadly looks at implications of sustainability for training in higher education (Barth, Godemann, Rieckmann, & Stoltenberg, 2007; Wals & Blewitt, 2010), including a specific focus on competencies for sustainability (Barth et al., 2007; Brundiers & Wiek, 2011; Wiek et al., 2011), there is less literature discussing the implications of TD research for postgraduate training (but see Enengel et al. (2012), Kemp & Nurius (2015), Muhar, Visser, & van Breda (2013), Nash (2008), and Pearce et al. (2018)).

While some universities have seen a growth in team- and applied-based approaches to postgraduate training and education for sustainability (Callaghan & Herselman, 2015; Larsson & Holmberg, 2018; Westley, Goebey, & Robinson, 2017), there has been limited training in approaches and competencies for conducting TD research at higher education institutions. Furthermore, there is a lack of recognition and trust in TD modes of research. For example, in South Africa, and in many institutions across the globe, Ph.D. program requirements still consist entirely of a research project, with limited coursework and time for orientation (Schmidt et al, 2012; Wolhuter, 2011). Therefore, many doctoral scholars attempt TD research outside of dedicated TD research programs or TD teams and without exposure to TD research-type competency development during undergraduate or postgraduate studies. The experiences of these scholars have not been subjected to much research.

Two Ph.D. Journeys in Transdisciplinary Research

Since TD research is an ambitious undertaking, should scholars consider using it for degree purposes? This chapter looks at the personal experiences of the two authors applying a TD approach in their Ph.D. studies. Both authors wanted to use a TD approach for Ph.D. studies because of its applied, problem-oriented, and transformative value, and because of a desire to strengthen their ability to act as change agents. By examining the individual experiences, insights about the competencies required for conducting TD research and the institutional enabling conditions for supporting these competencies at the postgraduate level were developed. These insights may aid in developing stronger TD training programs.

Petra Holden: Navigating Trade-offs between Disciplinary Rigor and the Ideal Transdisciplinary Process

My Ph.D. involved using a transdisciplinary (TD) approach to investigate the impact of mountain protection on ecosystem services in relation to broader socio-economic and ecological drivers of landscape change (Holden, 2018). Prior to my Ph.D., my postgraduate studies limited me to hypothetico-deductive research. In contrast, my undergraduate studies were referred to as a management degree, including three years of “theory” (what I would call pragmatic theory) and one year of full-time experiential work. I did not pursue a professional career in conservation management after my undergraduate program because I felt that, to fully engage science in management, I had to be exposed to and gain experience in “the research process.” However, during my postgraduate years at a formal university, I experienced challenges linked to disciplinary differences and perceptions on facts, rigor, causal explanation, and research goals, which I struggled to align with the necessity of doing applied research.

It was largely in response to these limitations that my desire for building a place for socially relevant research at research institutions grew. I was interested in understanding interconnections and feedbacks between systems. I valued a range of methods and knowledge sources, but I wanted to tackle problems that were meaningful outside of academia. I was frustrated with academia, therefore I left for a while to work in the field of climate change adaptation.

In this work, I noted the need for research information at multiple scales. For example, I needed information at both a water basin (larger catchment) and community or landscape (sub-catchment) levels to guide policy and implementation. I once again was frustrated because I felt that the projects within which I was working were not fully engaging with the complexity of the problems they were attempting to address. Therefore, when I started Ph.D. studies, I looked for funding that would support TD research and supervisors from various disciplinary backgrounds. I found a project with an ecologist, climate scientist/hydrologist, geographer, geomorphologist, economist, and a remote sensing expert (from five departments and three faculties at the University of Cape Town). My supervisors allowed me room to steer the project. At the outset, I engaged with landowners and managers to understand the situation and define the research focus.

Operationalizing TD research. Before writing my research proposal, I had interviews and informal discussions with conservation and fire managers, as well as local landowners. I matched their areas of concern, which were around land use, fire, and water, with appropriate literature, methods, and tools. I reviewed existing frameworks and concepts for understanding social-ecological change (Rissman & Gillon, 2017) including systems thinking (Kim, 1995; Meadows, 2008; Richmond, 1993), resilience thinking and theory (Folke, 2016; Folke et al., 2010), the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (Ostrom, 2009), and others (see reviews in Binder, Hinkel, Bots, & Pahl-Wostl (2013), Scholz (2013), and Cox et al., 2016).

I looked for a framework from sustainability science to integrate the different disciplinary results, however, none proved suitable (Shahadu, 2016). I, therefore, used the concept of pluralism (Isgren, Jerneck, & O’Byrne, 2017; Miller et al., 2008) to justify the use of various disciplinary aspects and to integrate the concepts of social-ecological systems, land use transitions, and ecosystem services into an overarching framework for protected area impact evaluation. Throughout the process, I engaged supervisors on a one-on-one basis regarding their specific areas of expertise. I also hosted three “workshops” that all the supervisors attended. Here, they focused on providing advice on how to reduce the workload to complete the Ph.D. within the expected time frame; there was almost no engagement of a TD nature. There was a concern that the Ph.D. program included too many approaches and aspects to fit into the expected Ph.D. time frame (three years). In these supervisor “workshops,” I presented detailed disciplinary methodologies and findings for all disciplines in the Ph.D. program and received detailed disciplinary insights from the supervisor who was a disciplinary expert in the respective field. In hindsight, I should have only focused on the TD aspects of the Ph.D. during these workshops and on how to integrate disciplinary aspects towards the central concerns in the landscape. It is likely that doing this would have required a focused methodology and efficient facilitation skills to bridge disciplinary epistemological differences.

Challenges to TD research. It was challenging to do all aspects of TD research (i.e., interdisciplinarity, co-creation, and knowledge integration) justice. I found it difficult to address all disciplinary requirements within the time and funding constraints, while also focusing on overarching applied research questions of a TD nature. I had to make trade-offs between achieving disciplinary rigor and achieving the “ideal” TD process.

In general, there was more pressure from my supervisors to obtain results separated out into their respective disciplinary domains than to obtain overarching, integrated results. A lack of all the supervisors having a mutual understanding of TD theory and methods limited the feedback that I could receive at a broader, integrated level. I struggled to consolidate the vast literature on transdisciplinarity and sustainability science into a succinct rationale for mixing methods. There were also differences between what landowners and managers viewed as interesting and relevant questions and results and what my supervisors and other academics viewed as necessary for doctoral research. Due to the emerging nature of the field, I also pre-empted that it was likely that my Ph.D. would be evaluated by disciplinary specialists rather than multi-method or TD researchers. This is because the notion of a “TD expert” is something that has not fully materialized in academia therefore individuals with these skills are often mixed in with disciplinary scientists.

In reflection, my efforts to achieve disciplinary rigor and to justify the various angles and approaches used for data, methods, and analyses side-lined other elements of the TD process. For example, although meaningful engagements with actors were achieved during the Ph.D. (e.g., co-design) and societal knowledge was integrated into the findings, there was a limited appraisal of the research findings in terms of relevance for actors in the landscape and a research management interface for driving change was absent.

Transdisciplinary research competencies. My modest positionality towards disciplines (i.e., believing that no discipline is in a better position than another to solve a problem or understand a situation (Augsburg, 2014)) enabled me to use and respect diverse disciplinary methodologies. However, I lacked insight and experience on how to trade-off disciplinary depth with integration and high-level systems thinking. I got lost in the details and struggled to integrate my empirical findings into novel and potentially transformative TD insights. I was also tied up with process-based stakeholder engagements and found it difficult to incorporate these informal processes into an examinable product (i.e., the dissertation). Although I had a supervisor with qualitative expertise, and I drew on these strengths for analyzing in-depth interview data, I was running out of time due to the magnitude of the work, as well as funding constraints.

I would have benefited from structured training opportunities in multi-method quantitative and qualitative case study research including a range of methodologies from “soft” to “hard” approaches for multiple fields. Guides to the basics of research methodology (such as epistemology, ontology, and associated methods) would have also been useful, along with guides for optimizing the use of disciplinary-specific methods for achieving transdisciplinarity and how to overcome the limits of compartmentalized research. Stronger systems thinking and exposure to the diagrammatic tools that systems thinkers use to communicate their research approaches, methods, and results would have been beneficial for me.

Box 1: Petra Holden’s Ph.D. research: A pluralistic-socio-ecological approach to understand the long-term impact of mountain conservation.

In this research, I used a TD approach to understand long term (> 60 years) change in the fire, water flow, land use, and vegetation cover in relation to mountain protection. The study area was a mountain catchment important for regional water supplies and of significant biodiversity importance in the Western Cape of South Africa. I built upon progress made in protected area impact evaluation (Ferraro & Hanauer, 2015), especially the use of counterfactuals (Epstude & Roese, 2008), with concepts from sustainability science, conservation biology, and land change science.

I used multiple disciplines including ecology, hydrology, geomatics, and environmental geography and tools such as vegetation surveys, repeat photographs, GIS (Geographic Information System mapping), mixed methods for social research, hydrological modeling, remote sensing, and scenario planning. I engaged with local actors to understand the situation (Mitchell et al., 2015) and to inform research design, and I used in-depth interviews to include landowner knowledge in research findings (Walter, Helgenberger, Wiek, & Scholz, 2007). I used pluralism (Isgren et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2008) to incorporate multiple epistemologies, philosophical viewpoints, and methodologies.

My findings showed that streamflow reductions and increased land fragmentation would have occurred without the protected area in the landscape. However, with increased water storage and fragmentation outside the protected area came socio-economic opportunities such as employment and local opportunities for ecotourism and sustainable agriculture. Interactions between global and local drivers were prominent causal mechanisms of socio-ecological change and defined protected area impact. Based on these findings, I highlighted the importance of maintaining various forms of land management in mountain ecosystems.

Photos: Left: Vegetation identification along surveys within the protected area Right: Informal meetings with landowners from the farming settlement outside the protected area.

Jessica Cockburn: Learning-by-Relating: Discovering New Competencies for Transdisciplinary Ph.D. Research

My Ph.D. research was a transdisciplinary (TD) inquiry on environmental stewardship and collaboration in multifunctional landscapes (Cockburn, 2018). Having worked as an environmental stewardship practitioner before starting the Ph.D., I wanted to conduct research that was relevant and useful to stewardship practitioners and that addressed important sustainability challenges. Transdisciplinary research enabled me to do science with society. Also, since sustainability science is a normative field of research (Wiek et al., 2011), it enabled me to be open about my values and my positionality.

To get started, I found a team of open-minded supervisors willing to support me and a nurturing ‘TD-friendly’ environment in the Department of Environmental Science at Rhodes University. Since I was not enrolled in a TD research postgraduate program, my supervisors and I were experimenting and acting as ‘bricoleurs’ to design and implement a TD study within the time and funding allowances of an individual Ph.D. project. We drew on the TD literature, on colleagues with expertise in supporting TD research (see Palmer, Biggs, & Cumming (2015), and on a TD community of practice at our university (see Wolff et al. (n.d.), and Cockburn & Cundill (2018)).

Operationalizing TD research. To guide the implementation of TD research, I drew on principles proposed by Lang et al. (2012) and on methodologies and theories across a wide range of disciplines and fields including natural resource management, biodiversity conservation, social-ecological systems and resilience, environmental governance, rural development, critical social theory, and environmental history. Guided by Price (2014), I used critical realism as a philosophical underlaborer and an analytical lens to strengthen and deepen knowledge integration across disciplines and contexts.

Transdisciplinary research requires building relationships with “societal actors” (van Breda et al., 2016, p. 156). I partnered with nongovernmental organizations that are facilitating multi-stakeholder collaboration for stewardship in rural landscapes. Through an opportunistic and iterative process (over ±1 year), I developed three distinct TD teams (i.e., communities of practitioners working at different levels and in different areas on stewardship and integrated landscape management).

Challenges to TD research. Along the way, I experienced four key challenges. First, I was frequently challenged by the multiple roles I had to play: researcher, facilitator, knowledge broker, mediator, and friend. I was somewhat unprepared for this and had to quickly take responsibility for my actions and everyday research ethics challenges and appreciate my shifting identity within each of these roles. Second, reconciling the, sometimes, mismatched purposes and demands of an academic research process with the expectations of practitioner partners was difficult and was compounded by time and budget constraints. Third, managing interpersonal relationships was personally and professionally challenging. I often wondered whether I had been communicating effectively with all the different partners, whether I had included all the right people in my emails, and whether I could find time and money to visit practitioners on-site and participate in their work. I often felt pulled in different directions and, at times, exhausted by the need to be everything to everyone. Fourth, I felt that I had to sacrifice depth for breadth. I worked ‘at breadth,’ across the knowledge divide between academia and practice, possibly trading off time to engage deeper in academic knowledge. I also worked across the knowledge divides between disciplines, covering a breadth of disciplinary knowledge, but not going into depth in any one discipline.

Transdisciplinary research competencies. In the process of building new relationships with practitioners, it became apparent that I needed to develop competencies and practices that conventional postgraduate research may not require. For my research to be societally relevant, I had to not only develop technical (academic) competencies related to critical thinking and systems thinking but also relational and translational competencies. This meant taking the time to build trust and manage interpersonal relationships with practitioner partners and mediate between different knowledge systems. I had to learn translational competencies by being a broker between academic and practice-based knowledge systems and by co-creating research questions with practitioner partners that were relevant in both practice and academic research. I spent time on non-research activities such as social events and practitioner meetings and workshops. I also had to manage expectations and communicate regularly with all three of my TD teams to ensure that we understood each other’s interests.

Along with developing relational and translational competencies, I also realized the importance of developing reflexive competence. I found that embedding reflexivity into my research practice helped me manage the balance between the demands of the academic system versus the often very different demands of working with practitioners. I learned reflexive habits of mind by not only reflecting (i.e., ‘looking into the mirror’ and thinking about what happened) but also considering the assumptions and conditions that underpin events and experiences (i.e., looking ‘through the mirror’ and reflecting on the nature of society and on my own value system and beliefs and responding accordingly (Bolton, 2010)). The practices that helped me embed these reflexive habits included disciplined personal journaling and connecting with others doing similar work through communities of practice (Cockburn & Cundill, 2018).

Developing new competencies to effectively practice TD research has helped me to think more carefully about what it means to be a change agent within academia that supports visions for sustainability. I have realized that we need to have a reflexive learning orientation. The world is changing quickly, and our roles, positions, and responsibilities are shifting. We need to navigate this rapidly changing world with an open mind, an open heart, and an open will (Scharmer & Kaufer, 2013).

Box 2: Stewardship and collaboration in multifunctional landscapes – Jessica Cockburn’s PhD research

The aim of my research was to conduct a TD investigation of the practice of stewardship and collaboration in multifunctional landscapes in South Africa. The research spanned social and ecological disciplines and integrated local practitioner knowledge to gain a grounded understanding of stewardship and collaboration. The methodology drew on transdisciplinarity, critical complexity, and critical realism which I integrated to develop a framework and a set of guiding principles. I first conducted a country-wide survey to investigate how practitioners put stewardship into practice. Based on this, I selected six cases of landscape-level stewardship initiatives where practitioners were working with local stakeholders to facilitate collaboration. In these case studies, I facilitated knowledge co-production processes, working closely with practitioners to develop a qualitative, place-based understanding of stewardship and collaboration. I then applied a critical realist methodology, developing a deeper TD understanding to explain my place-based research findings and reveal general trends applicable across contexts. I distilled the following key research findings:

- Practitioners should refocus stewardship on stewards to enable human agency;

- In multifunctional landscapes, a patchwork approach which recognizes diversity and values pluralism is necessary to support collaboration; and

- Practitioners should focus on building new interpersonal relationships among diverse stakeholders to support collaborative stewardship.

Photos: Left: An on-site conversation with a stewardship practitioner. Right: The Langkloof case study is an example of a multifunctional landscape which is valued by different stakeholders for different functions such as water, agriculture, tourism, and biodiversity conservation.

Discussion and Recommendations

This section discusses an analysis of the two TD research journeys shared above, integrating the reflections of Cockburn and Holden with insights from the literature. First, the focus is on competencies needed for TD research using the three-part framing described in the introduction (interdisciplinarity, co-creation, and knowledge integration). Second, provisions that should be made in institutions of higher education to support Ph.D. TD scholars in enabling the development of sustainability change agents was considered.

Developing TD Competencies

Currently, doing TD research might be one of the best ways for scholars to develop TD competencies. The field of TD research is progressing as more scholars attempt individual TD Ph.D. studies, building an increasing understanding of the type of competencies required for doing TD research. This section reflects on the competencies that Cockburn and Holden found they needed to undertake TD research, building on similar experiences reported in the literature.

Interdisciplinarity. The first insight that scholars of TD research will need is that there is more than one way to do TD research (Mitchell et al., 2015). The approach chosen depends on the nature of the research question, interest, and scope as co-defined by the relevant stakeholders. Other features of the context include funding and time frames and the background, experience, and interests of the lead researcher (Maxwell, 2012). While there are many approaches to TD, this does not mean that ‘anything goes.’ Transdisciplinary researchers clearly need to know how to navigate and apply research methods suitable to TD studies with rigor and to an acceptable quality, a finding described elsewhere by early-career researchers following an ‘undisciplinary’ postgraduate research journey (Haider et al., 2018). For example, Holden needed to know what would be regarded as an appropriate, credible, and defensible approach to TD in her study and both scholars had to develop a coherent overarching framework within which to situate diverse theories and methodologies.

Intellectual and methodological creativity are arguably hallmarks of Ph.D. studies because of the need to make an original contribution to the field (Mullins & Kiley, 2002). However, TD presents scholars with additional demands for being intellectually and methodologically creative while still producing defensible research. The research stories reflect the vast swathe of literature that TD scholars need to engage with and the choice of what to include and what to leave out seems just as important as the ability to master the chosen content. Both scholars needed to be creative in juggling often conflicting demands and mediating how far to go into one area, whether literature or data collection or stakeholder engagement, before moving on to address another. Both Ph.D. scholars noted the challenge of mediating depth versus breadth, illustrating the importance of technical competencies, such as systems thinking (Wiek et al., 2011), to support the rigorous and coherent application of multiple and diverse methodological and theoretical approaches.

Cockburn mentioned the value of engaging with supervisors and/or other scholars who have experience with TD research. Some research decisions still need to be made by the individual, so it is significant that Cockburn mentions reflexivity, the ability to start thinking of herself as a researcher and knowledge-producer and understand how her research decisions are being shaped by wider contexts and cultures by not only looking in the mirror and noting her own decisions but also looking ‘through the mirror’ into the long history that has shaped scientists’ decisions. This reflexivity is a high level of relational and, arguably, transformational competence because it allows people to see themselves in relation to a scholarly community and recognize historical, cultural, and ideological factors that shape decisions about how research should be done and valued. This enables researchers to transcend the boundaries of disciplinary decision-making, while still making logical and defensible decisions in the interest of credible knowledge creation.

Co-creation. Since TD research is an engaged process of knowledge co-production between academic and societal actors (Lang et al., 2012), building and maintaining relationships with a team of societal actors becomes a primary task in the doctoral research process (van Breda et al., 2016). This relational competency is needed to successfully conduct a TD study and, after graduation, to successfully function as a sustainability leader and change agent, particularly since sustainability transitions almost always involve collectives rather than individuals (Wiek et al., 2011). However, both scholars found stakeholder engagement difficult for different reasons.

Cockburn engaged extensively with stakeholders in various areas outside academia. She experienced several challenges in the process: managing stakeholders’ expectations, managing the contrasting interests of stakeholders and academia (also noted by Holden), and feeling poorly prepared for the interpersonal nature of the required engagements. She learned to play multiple roles in her work, operating as a broker, translator, and mediator. If well supported and well executed, navigating such challenges can build relational competencies that will help a scholar achieve good standing both inside and outside of academia (Scharmer & Kaufer, 2013).

Holden’s research journey illustrated that when a scholar is focused on juggling the disciplines in-depth, there can be little time and funding left for engaging stakeholders, especially at the end of the Ph.D. journey. While most research projects will have funding and time constraints, here the researcher had to make a call on whether to spend the time and funding on stakeholder engagement or on gathering further technical data. Cockburn’s example of worrying whether her email communications included all relevant parties suggests that details can be significant in stakeholder engagement and illustrates the kind of skill needed by change agents who intend to “walk with others” in addressing sustainability challenges. As an African proverb notes: “S/he who wants to walk fast, walks alone; s/he who wants to walk far, walks with others.”

Is it the role of supervisors to help develop relational competencies (Wiek et al., 2011) while also supporting scholars in gaining a deeper understanding of the literature and research methodology suitable to their studies (technical competencies)? What happens if they have not had such experiences themselves? Is there time for this? What suffers if attention is given to this – generally ‘new’ – dimension of scientific studies? Fortunately, some subfields in community development studies, adult education, and other social sciences have produced guidelines for stakeholder engagement and various forms of participatory research processes (Block, 2018; Bradbury, 2015). Even with guidelines, these processes are still challenging, but scholars do not have to design them entirely from scratch. This is, however, yet another field scholars need to come to grips with, made even more difficult if none of their supervisors have related experience.

Knowledge integration. The case stories demonstrate how, in the quest to integrate and transcend disciplinary academic knowledge, scholars have to move outside their comfort zones (i.e., beyond what is familiar based on their prior studies). Doctoral scholars, as individuals, thus need to “be transdisciplinary in their own heads” (van Kerkhoff, 2014; Max-Neef, 2005).

The challenge of integration is clear from Holden’s research story. This pertains both to using multiple methods from different disciplines in an integrative manner and integrating knowledge with diverse origins. Supervised only by disciplinary specialists, and lacking a TD specialist in her supervisor team, Holden was concerned that her thesis would be examined exclusively by disciplinary experts. Because of this, she gave less attention to integrating knowledge that would span across the disciplines. A reduced focus on knowledge integration was also likely influenced by her not finding a suitable integrating framework.

In Cockburn’s case, a realist framing provided a common ontological and epistemological base where knowledge from different scientific disciplines, as well as non-scientific knowledge, could find its place in reflecting the layered nature of complex reality (Bhaskar, 2016; Sayer, 2010). Conceptual and philosophical frameworks that allow for a robust, defensible integration across different knowledge sources and knowledge forms seem essential.

Earlier it was noted that both Ph.D. scholars were challenged by trying to mediate between depth and breadth. This amounts to technical competence in one knowledge area (depth) vs. technical and relational competencies to integrate across more than one knowledge area (van Kerkhoff, 2014; Wiek et al., 2011). Rosenberg et al. (2018) and Rosenberg et al. (2016) showed that employers of scientists require both depth specialists and breadth specialists and that change agents value having in-depth knowledge about certain aspects, the ability to recognize and work with other depth specialists, and the ability to apply such specialist knowledge in contexts requiring a broad perspective. But, how should such agile, integrative, systems-thinking competencies be taught and examined at a university?

Institutional Provisions for TD Research

There are many institutional challenges that individual Ph.D. scholars striving for a TD approach to their research experience face. In response to the institutional challenges that Cockburn and Holden experienced during their TD Ph.D. studies, this section reflects on what universities could focus on to support the development of change agents through TD research. The focus is on communities of practice, training, supervision, and assessment.

- Company and structured training on the research journey. The TD literature calls for team-based approaches to conducting research to cover the necessary breadth and depth and range of competencies required to address wicked sustainability challenges. This range of competencies is seldom, if ever, present in one change agent (Rosenberg et al., 2016). This suggests that it would be wise to undertake TD research as a team activity (Kemp & Nurius, 2015). While the Ph.D. journey is, in South Africa at least, primarily an individual undertaking, this research recommends that universities explore other models that include cohorts of scholars working together in Living Labs (Callaghan & Herselman, 2015), Challenge Labs (Larsson & Holmberg, 2018), or Change Labs (Westley et al., 2017).

Holden recommends providing TD researchers with structured training relevant to TD research. Short courses (e.g., summer/winter schools) can address at least two identified needs. First, they can provide technical information about TD approaches, research methodology, analytic tools, and stakeholder engagement, thus complementing and extending the expertise of supervision panels so that they are able to provide the breadth of technical and relational input that a TD scholar requires.

Second, such courses – particularly if their delivery mode is face-to-face – could act as the start of professional networks of scholars who could continue to engage with each other long after courses have been completed (Rosenberg et al., 2018, 2016). Communities of practice noted by Cockburn and other researchers (van Breda et al., 2016; Rosenberg et al., 2018, 2016) provide TD researchers with a collegial community in which to share challenges, difficult decisions, reflections, new ideas, and resources.

Based on Cockburn and Holden’s experiences, they agree with Kemp & Nurius’ (2015) suggestion for a scaffolded, developmental approach to supporting and training TD scholars in higher education. Such an approach recognizes that doctoral scholars are on an incremental, personal growth trajectory and that TD learning should align with this developmental trajectory. This trajectory requires careful institutional, pedagogical, and interpersonal scaffolding (support), not only through formal training courses but also through carefully designed research experiences, mentorship, advice, and interaction with peers (Kemp & Nurius, 2015).

- Quality criteria for appropriate supervision and assessment of TD research. Doctoral research is often fundamentally an individual endeavor and scholars are assessed according to their performance in the process of producing academic knowledge as independent researchers (Mullins & Kiley, 2002; Petre & Rugg, 2010). Yet, TD research is a collective endeavor. Therefore, is TD more demanding than mainstream scientific research? How should universities examine and value it? Scholars’ uncertainty as to how their TD work will be examined should be reduced.

The newness of TD research in some institutions should not be a reason for scholars to assume that they are the first to undertake TD research. Supervisors have a responsibility to introduce them to the growing body of literature and to courses that help scholars gain in-depth insights into specific knowledge or methodological areas relevant to a study. Where supervisors lack the necessary breadth of knowledge, as they are likely to do, the supervision panel needs to be expanded. It is important to have at least one experienced TD researcher on a panel. Furthermore, ideally, TD research should be examined by experts in TD research. This makes it doubly important to produce TD research academic quality criteria (Mitchell & Willetts, 2009), research ethics (Cockburn & Cundill, 2018), and stakeholder engagement (Reed et al., 2009) standards and guidelines that can be applied by examiners and supervisors, even if they are not experts in TD research.

It becomes apparent from the reflections and recommendations that the institutional changes required to support doctoral scholar TD research span the length and breadth of the academic system, from pedagogy in postgraduate teaching to assessment and examination to the professional development of supervisors and examiners to incentive structures and recognition of the value of diverse knowledge types and societal competencies. Another African proverb states that, “It takes a village to raise a child.” This research acknowledges that ‘it would take a whole system to enable TD research.’

Conclusion

In this chapter, two Ph.D. scholars shared their stories of pioneering TD research journeys for degree purposes. In reflecting on these journeys, insights into the kinds of competencies that scholars need to conduct TD research were gained. It became clear what competencies were relevant to their future work as TD researchers, practitioners, and/or research supervisors. The types of institutional arrangements that would make future TD research easier for other scholars, prospective change agents, and future sustainability leaders were also discovered.

The experience suggested that, in order to conduct TD research, one needs technical knowledge of and methodological competence in a number of disciplinary fields; knowledge of and the skill to apply one or more integrative frameworks; knowledge of and ability to use and defend methods, tools, and techniques that deal with a variety of data forms; high levels of relational skills to engage a variety of stakeholders and manage their expectations; project management skills including decision-making and prioritization with budgetary and time constraints; reflexive competence to understand the historical, cultural, and intellectual bases for decision-making; and communication skills to successfully convey and justify the research approach and findings.

While some of the knowledge necessary for sustainability science change agents and leaders is already in the system and can be accessed by new scholars, many of the skills and framings required cannot simply be learned from others. Many skills need to be developed and require scholars to be intellectually creative as well as be able to cope with high levels of uncertainty and complexity and be productive within those levels. Furthermore, they need to be able to ply their craft in the company of others since sustainability challenges are unlikely to be solved single-handedly.

Universities need to provide supervisors and examiners with TD experience, a range of courses that support TD and alternative models for the singular scholarly journey. An entire scholarly community is needed to work on frameworks and tools for conceptual and data integration; to provide collegial and intellectual homes for new TD scholars; and to determine credible quality criteria, research ethics, and stakeholder engagement guidelines for TD research.

The challenge of TD research is heightened by the constraints of existing Ph.D. timelines and current academic incentive structures that focus on quick turnaround periods and academic outputs rather than process-based outputs which are important for collaborative TD research. Conducting TD postgraduate research requires more time to ensure inclusivity across all three aspects of the TD process: co-creation, interdisciplinarity, and integration. As noted above, this African proverb captures the spirit of TD as a collaborative, and therefore slower, process: “S/he who wants to walk fast, walks alone; s/he who wants to walk far, walks with others”.

At this time, TD research involves creating a newly made path. The experience of those who are operationalizing TD in an academic context is therefore invaluable. Transdisciplinary scholars who wish to work towards transformation in society through an innovative approach to research may – at least for the foreseeable future – also need to be change agents within the institutions where they undertake their studies.

References

Augsburg, T. (2014). Becoming transdisciplinary: The emergence of the transdisciplinary individual. World Futures, 70(3-4), 233-247.

Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M., & Stoltenberg, U. (2007). Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(4), 416-430.

Bhaskar, R. (2016). Enlightened common sense: The philosophy of critical realism. Oxon: Routledge.

Binder, C., Hinkel, J., Bots, P., & Pahl-Wostl, C. (2013). Comparison of frameworks for analyzing social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 18(4), 26.

Block, P. (2018). Community: The structure of belonging. Oakland, California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Bolton, G. (2010). Reflective practice: Writing and professional development. London: Sage publications.

Bradbury, H. (2015). The SAGE handbook of action research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

Brundiers, K. & Wiek, A. (2011). Educating students in real-world sustainability research: Vision and implementation. Innovative Higher Education, 36(2), 107-124.

Callaghan, R. & Herselman, M. (2015). Applying a Living Lab methodology to support innovation in education at a university in South Africa. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(1), 21-38.

Cockburn, J. (2018). Stewardship and collaboration in multifunctional landscapes: A transdisciplinary enquiry. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Grahamstown:Rhodes University.

Cockburn, J. & Cundill, G. (2018). Ethics in transdisciplinary research: Reflections on the implications of “Science with Society.” In Macleod, C and Marx, J and Mnyaka, P and Treharne, G (Ed.), Handbook of Ethics in Critical Research: Stories from the field (pp. 81–97). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cox, M., Villamayor-Tomas, S., Epstein, G., Evans, L., Ban, N. C., Fleischman, F., … Garcia-Lopez, G. (2016). Synthesizing theories of natural resource management and governance. Global Environmental Change, 39, 45-56.

Dedeurwaerdere, T. (2013). Transdisciplinary sustainability science at higher education institutions: Science policy tools for incremental institutional change. Sustainability, 5(9), 3783-3801.

Enengel, B., Muhar, A., Penker, M., Freyer, B., Drlik, S., & Ritter, F. (2012). Co-production of knowledge in transdisciplinary doctoral theses on landscape development—An analysis of actor roles and knowledge types in different research phases. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(1), 106-117.

Epstude, K. & Roese, N. J. (2008). The functional theory of counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(2), 168-92.

Ferraro, P. J. & Hanauer, M. M. (2015). Through what mechanisms do protected areas affect environmental and social outcomes? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B, 370(1681), 20140267.

Folke, C. (2016). Resilience (Republished). Ecology and Society, 21(4), 44.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockstrom, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15, 20.

Hadorn, G. H., Biber-Klemm, S., Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W., Hoffmann-Riem, H., Joye, D., Pohl, C., … Zemp, E. (2008). Handbook of transdisciplinary research (Vol. 10). Dordrecht: Springer.

Haider, L. J., Hentati-Sundberg, J., Giusti, M., Goodness, J., Hamann, M., Masterson, V. A., Meacham, M., et al. (2018). The undisciplinary journey: Early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 13(1), 191-204.

Holden, P. B. (2018). A pluralistic, socio-ecological approach to understand the long-term impact of mountain conservation: a counterfactual and place-based assessment of social, ecological and hydrological change in the Groot Winterhoek Mountains of the Cape Floristic Region. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Isgren, E., Jerneck, A., & O’Byrne, D. (2017). Pluralism in search of sustainability: Ethics, knowledge and methodology in sustainability science. Challenges in Sustainability, 5(1), 2-6.

Kemp, S. P. & Nurius, P. S. (2015). Preparing emerging doctoral scholars for transdisciplinary research: A developmental approach. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35(1-2), 131-150.

Kim, D. H. (1995). Systems thinking tools: A user’s reference guide. Waltham, Massachusetts: Pegasus Communications.

Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., … Thomas, C. J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 25-43.

Larsson, J. & Holmberg, J. (2018). Learning while creating value for sustainability transitions: The case of Challenge Lab at Chalmers University of Technology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4411-4420.

Max-Neef, M. A. (2005). Foundations of transdisciplinarity. Ecological Economics, 53(1), 5-16.

Maxwell, J. A. (2012). A realist approach for qualitative research. United States: SAGE.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems – a primer –. London: Earthscan.

Miller, T. R., Baird, T. D., Littlefield, C. M., Kofinas, G., Chapin III, F. S., & Redman, C. L. (2008). Epistemological pluralism: Reorganizing interdisciplinary research. Ecology and Society, 13(2), 46.

Mitchell, C., Cordell, D., & Fam, D. (2015). Beginning at the end: The outcome spaces framework to guide purposive transdisciplinary research. Futures, 65, 86-96.

Mitchell, C. & Willetts, J. (2009). Quality criteria for inter- and trans-disciplinary doctoral research outcomes. Prepared for ALTC fellowship: Zen and the art of transdisciplinary postgraduate studies. Sydney, Australia: Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology.

Muhar, A., Visser, J., & van Breda, J. (2013). Experiences from establishing structured inter- and transdisciplinary doctoral programs in sustainability: A comparison of two cases in South Africa and Austria. Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 122-129.

Mullins, G. & Kiley, M. (2002). “It’s a PhD, not a Nobel Prize”: How experienced examiners assess research theses. Studies in Higher Education, 27(4), 369-386.

Nash, J. M. (2008). Transdisciplinary training: Key components and prerequisites for success. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), S133-S140.

Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325(419).

Palmer, C. G., Biggs, R., & Cumming, G. S. (2015). Applied research for enhancing human well-being and environmental stewardship: Using complexity thinking in Southern Africa. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 53.

Palmer, J., Fam, D., Smith, T., & Kent, J. (2018). Where’s the data? Using data convincingly in transdisciplinary doctoral research. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 9-29.

Park, P. (2006). Knowledge and participatory research. In P. Reason and H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research (pp. 83–93). London: Sage.

Parker, J. & Crona, B. (2012). On being all things to all people: Boundary organizations and the contemporary research university. Social Studies of Science, 42(2), 262-289.

Pearce, B., Adler, C., Senn, L., Krütli, P., Stauffacher, M., & Pohl, C. (2018). Making the link between transdisciplinary learning and research. Transdisciplinary Theory, Practice and Education, 167-183.

Petre, M. & Rugg, G. (2010). The unwritten rules of PhD research. Berkshire, United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill International/Open University Press.

Polk, M. (2014). Achieving the promise of transdisciplinarity: A critical exploration of the relationship between transdisciplinary research and societal problem solving. Sustainability Science, 9(4), 439-451.

Price, L. (2014). Critical realist versus mainstream interdisciplinarity. Journal of Critical Realism, 13(1), 52-76.

Reed, M. S., Graves, A., Dandy, N., Posthumus, H., Hubacek, K., Morris, J., … Stringer, L. C. (2009). Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1933-1949.

Richmond, B. (1993). Systems thinking: Critical thinking skills for the 1990s and beyond. System Dynamics Review, 9(2), 113-133.

Rissman, A. R. & Gillon, S. (2017). Where are ecology and biodiversity in social-ecological systems research? A review of research methods and applied recommendations. Conservation Letters, 10(1), 86-93.

Rosenberg, E., Lotz-Sisitka, H. B., & Ramsarup, P. (2018). The green economy learning assessment South Africa: Lessons for higher education, skills and work-based learning. Higher Education, Skills and Work-based Learning, 8(3), 243-258.

Rosenberg, E., Ramsarup, P., Gumede, S., & Lotz-Sisitka, H. (2016). Building capacity for green, just and sustainable futures-A new knowledge field requiring transformative research methodology. South African Journal of Education, 65, 95-122.

Sayer, A. (2010). Reductionism in social science. Questioning Nineteenth Century Assumptions about Knowledge, 5-39. New York, NY: SUNY Press

Scharmer, C. O. & Kaufer, K. (2013). Leading from the emerging future: From ego-system to eco-system economies. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Scholz, R. W. (2013). Environmental literacy in science and society. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Shahadu, H. (2016). Towards an umbrella science of sustainability. Sustainability Science, 1-12.

Stock, P. & Burton, R. J. (2011). Defining terms for integrated (multi-inter-trans-disciplinary) sustainability research. Sustainability, 3(8), 1090-1113.

Schmidt, A. H., Robbins, A. S., Combs, J. K., Freeburg, A., Jesperson, R. G., Rogers, H. S., … Wheat, E. (2012). A new model for training graduate students to conduct interdisciplinary, interorganizational, and international research. BioScience, 62(3), 296-304.

van Breda, J., Musango, J., & Brent, A. (2016). Undertaking individual transdisciplinary PhD research for sustainable development: Case studies from South Africa. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 17(2), 150-166.

van Breda, J. & Swilling, M. (2018). The guiding logics and principles for designing emergent transdisciplinary research processes: Learning experiences and reflections from a transdisciplinary urban case study in Enkanini informal settlement, South Africa. Sustainability Science, 1-19.

van Kerkhoff, L. (2014). Developing integrative research for sustainability science through a complexity principles-based approach. Sustainability Science, 9(2), 143-155.

Wals, A. E. & Blewitt, J. (2010). Third-wave sustainability in higher education: Some (inter) national trends and developments. In Jones, P., Selby, D. & Sterling, S (Eds.), Sustainability education, perspectives and practice across higher education (pp.70-89). Abingdon, Oxon: Earthscan.

Walter, A. I., Helgenberger, S., Wiek, A., & Scholz, R. W. (2007). Measuring societal effects of transdisciplinary research projects: design and application of an evaluation method. Evaluation and Program Planning, 30(4), 325-338.

Westley, F., Goebey, S., & Robinson, K. (2017). Change lab/design lab for social innovation. Annual Review of Policy Design, 5(1), 1-20.

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 1-16.

Wolff, M., Cockburn, J., de Wet, C., Carlos Bezerra, J., Weaver, M., Finca, A., … Palmer, C. (n.d.). The contributions of transdisciplinary research to sustainable and just natural resource management: Insights from the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Wolhuter, C. (2011). Research on doctoral education in South Africa against the silhouette of its meteoric rise in international higher education research. Perspectives in Education, 29(1), 126-138.

Yarime, M., Trencher, G., Mino, T., Scholz, R. W., Olsson, L., Ness, B., … Rotmans, J. (2012). Establishing sustainability science in higher education institutions: Towards an integration of academic development, institutionalization, and stakeholder collaborations. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 101-113.