Reimagining Insect Biology

Matt Petersen

How do you teach university students an appreciation for a group of animals that represent more than 50% of all described species on earth? Did I mention this group is typically seen as something to be dealt with, a pest, or just unwanted visitors in our homes. I’m talking about insects here, and they are fundamentally a part of our lives, whether we like it or not. I am amazed by insects, the countless forms and features of these animals are something to behold. For me, it was when I first started studying insect diversity that I truly began to understand the natural world.

Yet, I understand that not everyone shares my fascination with insects. In fact the majority of students in my introductory entomology courses are at times uneasy with insects, and often fairly disgusted by them. It is my job to move them away from this discomfort and to a place where they can understand the importance of insects.

It is easy to teach students why we need to know about insects. They threaten our way of life by impacting our health and destroying our crops. They are also important pollinators with parts of our food supply dependent on their actions. Because of these important, and close interactions, insect education is typically grounded in an anthropocentric viewpoint. That is documenting information based on how insects contribute to, or detract from, our way of life. These two ends of the spectrum represent two diametrically opposing viewpoints that present a common challenge, namely replacing pre-existing perceptions of insects with an understanding of insect biology.

But why the focus on changing pre-existing perceptions? It is because perceptions about insects can be misleading. They can often deflect from a holistic view of what insects are, and even the role insects have on our world. Harmful insect species spread disease, threaten our food supply, and can generally be a nuisance. However, our actions towards a few insect species that cause these issues threatens the existence of thousands of other insect species that present no threat. Perpetuating negative perspectives about insects without factual knowledge can lead to unnecessary environmental threat, such as unnecessary pesticide applications applied to “control” otherwise harmless insects. Positive perspectives about insects without factual knowledge can be equally damaging. Phrases such as “save the pollinators” can become broadly applied concepts, with little regard to the identity, biology, and ecological function of the insects involved. It is applied to managed livestock species such as Apis mellifera (Western honey bee) and species that provide minimal pollination services, such as Danaus plexippus (Monarch butterfly). This emphasis is not technically wrong, but it can divert effort, funding, and attention away from other insects that face serious threats. Such as the serious threats facing native pollinators that are critical to pollination networks. Ultimately, both positive and negative perceptions can cause misconceptions that may misrepresent the truth. This can help perpetuate true threats to insect populations.

My primary goal as an instructor of insect biology is to get students to understand and appreciate insects as animals, and leave previous perceptions about the group behind. Starting from this blank slate allows us to develop an idea of what insects are. My approach to insect education emphasizes understanding insect identity, physiology, and ecology. That means building an understanding of complex insect life-cycles, evolutionary history, morphology and physiology, and ecology. I do need to present a rich amount of information relating to these subjects. So as good and entertaining of an educator as I may be, this is a good amount of information and a lot for some students to take in. This task can be difficult, particularly for students with a limited background in biology.

A primary example of replacing perceptions with knowledge can be seen in my Insect Biology course I teach at the University of Minnesota. This is a large enrollment course delivered in an online lecture format. Engaging students in this format can be challenging. To do this, I use a semester-long active learning project called EveryDay Entomology. This project helps students form a foundational understanding of entomology by asking them to apply information learned in class and independent research to a project of their choice, in the medium of their choice. I challenge the students to use a medium that best suits their strengths, as matching learning activities with specific student interests can be key in engaging students in large enrollment courses (Aronson, 1987). Therefore the format of the projects are highly variable, including visual and auditory artistic pieces, detailed research papers, innovative business proposals, and educational displays. The common thread of all projects is that the biology of the insect should be at the forefront and students actively engage with content and apply facts and concepts is key. The use of active learning strategies connects students with the content in a personal way through a pedagogical approach that is documented to better engage students and increase their performance on course assessments (Freeman et al. 2014).

Three primary elements underlie the format of this exercise:

- Freedom of Format helps students actively synthesize course content through an individualized outlet. By reducing the emphasis on format, students can focus on gathering and integrating content. This freedom also builds student confidence in their ability to complete the project. By building confidence, students choose to work on the project (rather than being forced to do so).

- Literature Integration is emphasized by requiring students to use at least one scientific paper for each of three elements of insect biology. Insect morphology and physiology describe the physical elements of the insect body and describe how the organ systems function. Biodiversity and evolution describe the taxonomic identity of insects and the evolutionary processes underlying the diversity of this group of animals. Insect Ecology describes how insects interact with the surrounding environment. Written projects naturally incorporate these elements into the text. Visual and auditory projects include supplemental student submissions documenting the artistic process (how these elements were incorporated) and an artist’s statement (why these elements are important).

- Peer Mentoring allows students to critically evaluate the work of other students and to provide feedback on the clarity of insect biology integration. The students work in cohorts where members all work in the same project format. Throughout the semester students review, evaluate, and critique the work of others in their cohort. This peer-peer scaffolding helps clarify the learning objectives of the assignment and the associated networking helps to build a sense of belonging among students in the course.

While the underlying pedagogical research supports the utility of this project, my best evidence for the success of this project comes from the student outcomes themselves.

The “otherness” of insects can be captured in digital art:

“Typically, the average insect elicits a negative response from people, one of repulsion and/or disgust. Admittedly, I fall under that category. Now, I hope to challenge people to gaze upon insects frighteningly up-close and allow their disgust to morph into a twisted sense of awe. The vast diversity amongst insect morphology allows one to see the purpose behind their different alienesque forms. Maybe the reason why humans are so repulsed by insects is thanks to how uncomfortably alien they seem. This realization inspired my work’s concept of an astronaut floating in outer-space covered in unique insects like the atlas moth, orchid praying mantis, and the rainbow leaf beetle. These specific insects were chosen based on my personal opinion of how out-of-this-world they seemed. My work is intended to evoke an awe or sense of wonder towards insects and their interesting morphology. In other words, I hope someone can look at this piece and ponder upon why insects are shaped so horrifyingly alien.”

Insect development can be captured in song:

Vanessa cardui (in song) Adam Meyers

“The song starts out with the egg section (0:00 – 0:49). It simply consists of a held note on violin and string bass, with other instruments slowly chiming in with notes here and there, symbolizing the organism’s growth within the egg. The melody is an extremely simplified version of the larva theme that comes up later. Next I start the larva theme (0:49 – 2:00), which can be heard throughout the piece. This melody is very quick and relies more on the rhythm than the notes themselves. At first, the melody is simplified, and there are few instruments playing. However, after one run-through of the theme, we hit a chaotic couple of measures which represent the caterpillar molting. More musical layers are added after each molt, showing the growth of the caterpillar. This cabasa is used during the larva section in times where the caterpillar would be eating leaves, but after the larva section, it is not heard again. Partway through this section, a faint second melody can be heard, this is the adult theme. This is supposed to depict how some of the adult parts begin to form within the caterpillar during the larval stage. After the final molt, we transition into a much slower section, representing the pupal stage of the painted lady butterfly. While much of the insect is reconstructed during the pupal stage, certain aspects, such as the ganglia containing the memories, are maintained, keeping some of that larval identity intact. A simplified version of the larval theme throughout the whole section. The adult theme slowly takes over the piece, and eventually this simple larval theme becomes more of a background to a whole new melody. This theme has lots of rising notes, which really helps create an image of a butterfly in flight. However, the larval theme still never fully disappears from the song, as the butterfly is still the same organism as it was when it first came out of the egg, even maintaining its memories.”

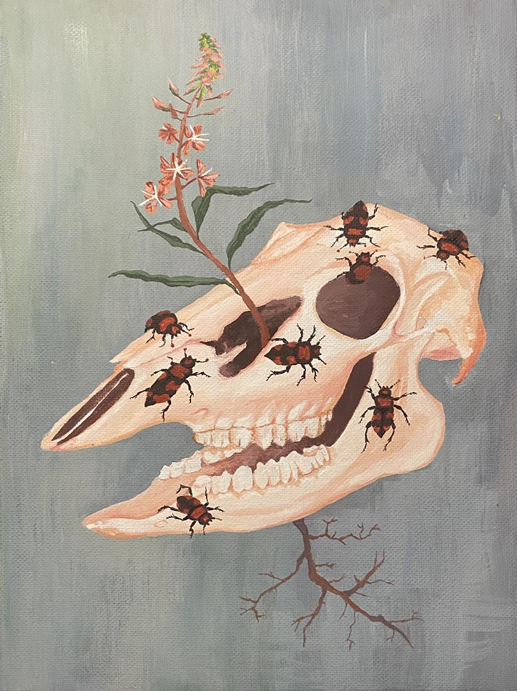

Insect ecology can be captured in a painting:

American Burying Beetle Haidyn Larson

“The main focus of the project was to convey the larger role insect detritivores have in an ecosystem. So, to do so, I used the ecology of Nicrophorus americanus, or the American Burying Beetle. The beetle is unfortunately considered endangered, so not only did I want to incorporate it for its striking looks, I also wanted to display it as a means of awareness. The burying beetle was last notably populous in Rhode Island, so the aspects of my painting aimed to reflect the ecology of that region. I included the skull of a white tail deer, the dead matter in the process of recycling energy, and fireweed, the living matter/product of recycled energy and native wildflower to Rhode Island. The anatomy of the beetle, the deer, and fireweed were individually examined and then arranged to resemble the process of energy/nutrient transference in a simultaneous display. The Burying beetle is one of many insect detritivores responsible for transferring energy within an ecosystem, and are a major contributor for diversity in organisms. Without them, many natural resources necessary for other organisms to thrive would not be nearly as available. Insect detritivores support the foundation of the food web, and both directly and indirectly support the different levels of organisms within it. The dead deer is recycled into plant material that can then feed an herbivore, which can in turn feed a predator, and then inevitably be recycled once more. In short, all levels of the web are affected and depend on detritivores such as the Burying beetle. For these reasons, they are an essential part of the natural world, and deserve a sense of appreciation.”

“The main focus of the project was to convey the larger role insect detritivores have in an ecosystem. So, to do so, I used the ecology of Nicrophorus americanus, or the American Burying Beetle. The beetle is unfortunately considered endangered, so not only did I want to incorporate it for its striking looks, I also wanted to display it as a means of awareness. The burying beetle was last notably populous in Rhode Island, so the aspects of my painting aimed to reflect the ecology of that region. I included the skull of a white tail deer, the dead matter in the process of recycling energy, and fireweed, the living matter/product of recycled energy and native wildflower to Rhode Island. The anatomy of the beetle, the deer, and fireweed were individually examined and then arranged to resemble the process of energy/nutrient transference in a simultaneous display. The Burying beetle is one of many insect detritivores responsible for transferring energy within an ecosystem, and are a major contributor for diversity in organisms. Without them, many natural resources necessary for other organisms to thrive would not be nearly as available. Insect detritivores support the foundation of the food web, and both directly and indirectly support the different levels of organisms within it. The dead deer is recycled into plant material that can then feed an herbivore, which can in turn feed a predator, and then inevitably be recycled once more. In short, all levels of the web are affected and depend on detritivores such as the Burying beetle. For these reasons, they are an essential part of the natural world, and deserve a sense of appreciation.”

References:

Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M.P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (23) 8410-8415.

Aronson, J. R. (1987). Six keys to effective instruction in large classes: Advice from a practitioner. In M. G. Weimer (Ed.), Teaching large classes well (pp. 31-37). San Francisco: JosseyBass.