Intergenerational Nature Journaling

Reba Luiken

In 2020 and 2021, intergenerational and homeschool learning at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum went online. As always, the goal was to give participants the opportunity to have a hands-on experience with nature as they learned together. I chose nature journaling as the main activity because it is something that both children and adults can practice together. Sometimes adults are the leaders, and other times children’s natural curiosity and other skills really shine. Plus, it integrates science and art in a compelling way. In order to bring hands-on activities into the virtual space, participants were asked to complete a scavenger hunt and sketching activity outside before class. We used these materials and expanded on them during class, and then participants were offered extension activities they could choose to complete on their own.

The Nature Journaling Academy was offered once a month to families with children ages 5-12 from September 2020 until April 2021 with a break in January. Each family received a Zoom link to participate in a live, un-recorded session, and children and caregivers were expected to attend together. Participants paid as a family (with 1 or more children) and registered for each session individually with a discount offered for multiple sessions.

Before class:

I emailed participants an information sheet with a to-do list including:

- Adopt a tree! (Keep the same tree from before if you already have one.)

- Observe your tree for 30 minutes – Pay special attention to birds and other animals that have been near your tree

- Complete your scavenger hunt

In September, for example, our theme was fruits and flowers, so participants were asked to collect a variety of fruits and flowers we could observe during class.

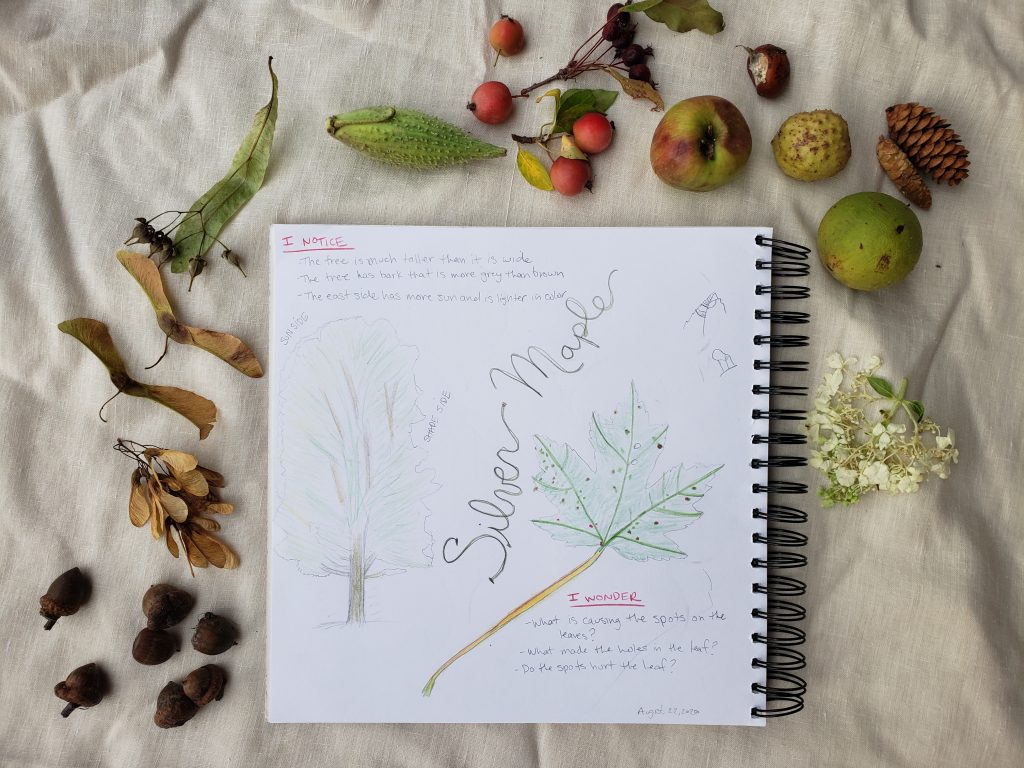

I adopted a silver maple tree that I could see from my window at home, which I drew for this class. I also suggested students might want to take pictures of their tree to see how it changed over the seasons, and I did that with my tree too!

In November, we focused on tree bark, and students were given the option to collect some birch bark. I gave them very specific instructions:

“Each person will use a strip of Birch bark about 1” wide and 3 to 12” long. Ideally, your strip would be 12” long however, it is MUCH more important to be respectful of our neighbor trees. Do not tear Birch bark from a tree. Instead, use a pair of scissors to cut bark that has already started to pull away from the trunk. Better yet, collect bark from the ground. If no bark is available, don’t despair! I’ll be modeling the process with a page of magazine paper too. You’ll likely have better luck finding bark in April, when Birch trees naturally shed their bark.”

In fact, none of the students brought bark with them to class, so we used paper for the activity.

Students were also asked to bring some basic supplies to use during class that could easily be found at home like paper and colored pencils or crayons. Over the course of the class series, the most difficult thing to find proved to be a true pine cone (rather than a spruce or fir).

During class:

We met for one hour together via Zoom which was shorter than our usual two hour in-person classes. Adults and children were expected to attend together. Each time we:

- did a nature journaling activity together,

- had a mini-lecture on one or more science topic,

- had small group sharing time, and

- did another hands-on activity like a short art project, science experiment, or game

During class in September, students learned about how flowers and fruits are related in a plant’s life cycle. We also talked about the parts of a flower and learned about compound flowers that have multiple small flowers called disk flowers and ray flowers clustered together to form a daisy or sunflower. Then we had fun taking our flowers apart as we created mandalas.

Our nature journaling activity for September was a shortened version of “I Notice, I Wonder, It Reminds Me Of.”[1] Students were challenged to spend five minutes writing down things they noticed (observations) with all of their senses. The difficult part is not writing down assumptions too. For example, if you take a look at a leaf that has brown around the edges, it is tempting to write or say that it is dying. However, noticing the brown edges is the real observation, whereas your brain has made some quick inferences when jumping to the conclusion that aren’t part of this step in the process.

The next five minutes were devoted to asking questions as we wondered about things. Here, students might ask why a leaf has brown edges or why different fruits were sweeter than others. We did not do any continuing investigations after asking these questions, but these could have been the start to us developing our own experiments. Instead, we had small group discussions with classmates about what we had written in our journals. I found that even though we usually only had about ten families joining, having discussions amongst smaller groups really allowed children to share more.

During November, our science topic was winter tree identification, and we talked about MAD trees (Maple-Ash-Dogwood) which are some of the few trees in Minnesota that have opposite branches. Our main activity, however, was sharing stories about how nature came to be the way it is today. I shared the Anishinaabe story of Manabozho and the Maple Trees which explains why we need to boil maple sap to make delicious maple syrup today. Students had lots of fun creating their own stories and drawing pictures to illustrate them. This was the most fun we had in any of our nature journaling sessions, and I highly recommend it! We ended the class by making birch bark beads using strips of paper since we did not have any birch bark.

After class:

I shared online resources and extension opportunities like at-home experiments, more nature journaling activities, and citizen science projects that participants could get involved with.

Some of the extension activities were things that I created and others were things that are already available online. For November, I created a StoryMap that included extension activities that centered Indigenous knowledge. It included a land acknowledgement statement in language that could be understood by children and incorporated the plants we had talked about in class alongside more nature journaling and storytelling activities.

For our March class, we focused on Maples, and I shared a Pressbook I had created for use by visitors who would have normally come to our Maple Fest or Maple Field Trips at the Arboretum. Again, this project centered indigenous knowledge and resources alongside hands-on inquiry in an interactive text. Unfortunately, not all of the links are still active.

Here are some of my most-recommended resources from other sources:

John Muir Laws Nature Journaling Resources: https://johnmuirlaws.com/

John Muir Laws is a professional nature journaling educator, and he’s written an excellent and free guide with ideas on using nature journals for learning. We used many of them in class (like I Notice, I Wonder, It Reminds Me Of), but you can find more on John’s website. He also has a list of suggested nature journal materials here: https://johnmuirlaws.com/field-sketching-equipment/

iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/

This site (and app on your phone) is great for helping to identify plants and animals you find during your outdoor explorations. Just take a picture on your phone or iPad and check out identification suggestions. (You don’t even need to make an account.)

Nature’s Notebook: https://www.usanpn.org/natures_notebook

If you’d like to turn your nature journaling and weekly tree visits into citizen science, Nature’s Notebook is a great place to start. Once you create an account and identify your tree, you can make weekly observations on seasonal changes.

Since completing these projects, I have moved on to a new position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I have had the opportunity to extend my knowledge of nature journaling for use in the college classroom with students in landscape architecture and horticulture. Modifying activities from John Muir Laws, I have challenged students to compare two similar plants, to draw and label a plant well enough for someone else to identify it, and to notice and wonder about the world around them. One of the special things about nature journaling is its ability to engage people of all ages and with a variety of backgrounds. Some learners bring more art experience or more technical scientific language, but curiosity and engagement are just as important!

I have also used nature journaling as reflective exercises for staff trainings and as a way to center myself. Drawing objects in the natural world is challenging because it takes both mental and physical concentration. By pulling all of one’s attention to the challenge at hand, it serves as an excellent way to calm down and release stress.

Here’s an activity you might try yourself:

- Find a natural object, a pen or pencil, and a timer (your phone works fine).

- Sit down somewhere you have a hard surface to draw on and set your timer for five minutes.

- Use this time to look carefully at your object and to draw, but don’t look down at your drawing. Keep your pencil always on the page and trust that your arm and your eyes are connected. They key is to actually look at the object rather than assuming it looks as it should. A real apple probably does not look like the apple you imagine in your mind.

- When the time is up, take a look at your drawing (or drawings) with curiosity rather than judgement. What did you learn? How do you feel now?

If you can set aside self-judgement about the quality of your work, you may well feel relaxed and refreshed. If you practice over time, you can improve your arm’s ability to follow your eye, but the key for this activity is to appreciate the process rather than the product.

- Laws, J. M. (n.d.). John Muir Laws: Nature Stewardship through Science, Education, and Art. John Muir Laws. Retrieved February 25, 2022, from https://johnmuirlaws.com/ ↵