Chapter 1: Introduction

What’s in It for Me?

- What is international business?

- Who has an interest in international business?

- What forms do international businesses take?

- What is the globalization debate?

- What is the relationship between international business and ethics?

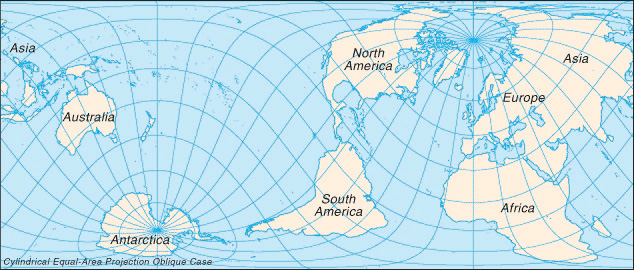

This chapter introduces you to the study of international business. After reading a short case study on Google Inc., the Internet search-engine company, you’ll begin to learn what makes international business such an essential subject for students around the world. Because international business is a vital ingredient in strategic management and entrepreneurship, this book uses these complementary perspectives to help you understand international business. Managers, entrepreneurs, workers, for-profit and nonprofit organizations, and governments all have a vested interest in understanding and shaping global business practices and trends. Section 1.1 “What Is International Business?” gives you a working definition of international business; Section 1.2 “Who Is Interested in International Business?” helps you see which actors are likely to have a direct and indirect interest in it. You’ll then learn about some of the different forms international businesses take; you’ll also gain a general understanding of the globalization debate. This debate centers on (1) whether the world is flat, in the sense that all markets are interconnected and competing unfettered with each other, or (2) whether differences across countries and markets are more significant than the commonalities. In fact, some critics negatively describe the “world is flat” perspective as globaloney! What you’ll discover from the discussion of this debate is that the world may not be flat in the purest sense, but there are powerful forces, also called flatteners, at work in the world’s economies. Section 1.5 “Ethics and International Business” concludes with an introductory discussion of the relationship between international business and ethics.

Opening Case: Google’s Steep Learning Curve in China

SEO – google – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Of all the changes going on in the world, the Internet is the one development that many people believe makes our world a smaller place—a flat or flattening world, according to Thomas Friedman, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century and The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization. Because of this flattening effect, Internet businesses should be able to cross borders easily and profitably with little constraint. However, with few exceptions, cross-border business ventures always seem to challenge even the most able of competitors, Internet-based or not. Some new international ventures succeed, while many others fail. But in every venture the managers involved can and do learn something new. Google Inc.’s learning curve in China is a case in point.

In 2006, Google announced the opening of its Chinese-language website amid great fanfare. While Google had access to the Chinese market through Google.com at the time, the new site, Google.cn, gave the company a more powerful, direct vehicle to further penetrate the approximately 94 million households with Internet access in China. As company founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin said at the time, “Unfortunately, access for Chinese users to the Google service outside of China was slow and unreliable, and some content was restricted by complex filtering within each Chinese ISP. Ironically, we were unable to get much public or governmental attention paid to the issue. Although we dislike altering our search results in any way, we ultimately decided that staying out of China simply meant diminishing service and influence there. Building a real operation in China should increase our influence on market practices and certainly will enhance our service to the Chinese people” (Page & Brin, 2005).

A Big Market, Bigger Concerns

Google’s move into China gave it access to a very large market, but it also raised some ethical issues. Chinese authorities are notorious for their hardline censorship rules regarding the Internet. They take a firm stance against risqué content and have objected to The Sims computer game, fearing it would corrupt their nation’s youth. Any content that was judged as possibly threatening “state security, damaging the nation’s glory, disturbing social order, and infringing on other’s legitimate rights” was also banned (Oates, 2004). When asked how working in this kind of environment fit with Google’s informal motto of “Don’t be evil” and its code-of-conduct aspiration of striving toward the “highest possible standard of ethical business,” Google’s executives stressed that the license was just to set up a representative office in Beijing and no more than that—although they did concede that Google was keenly interested in the market. As reported to the business press, “For the time being, [we] will be using the [China] office as a base from which to conduct market research and learn more about the market” (Sherriff, 2005). Google likewise sidestepped the ethical questions by stating it couldn’t address the issues until it was fully operational in China and knew exactly what the situation was.

One Year Later

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

Google appointed Dr. Kai-Fu Lee to lead the company’s new China effort. He had grown up in Taiwan, earned BS and PhD degrees from Columbia and Carnegie Mellon, respectively, and was fluent in both English and Mandarin. Before joining Google in 2005, he worked for Apple in California and then for Microsoft in China; he set up Microsoft Research Asia, the company’s research-and-development lab in Beijing. When asked by a New York Times reporter about the cultural challenges of doing business in China, Lee responded, “The ideals that we uphold here are really just so important and noble. How to build stuff that users like, and figure out how to make money later. And ‘Don’t Do Evil’ [referring to the motto ‘Don’t be evil’]. All of those things. I think I’ve always been an idealist in my heart” (Thompson, 2006).

Despite Lee’s support of Google’s utopian motto, the company’s conduct in China during its first year seemed less than idealistic. In January, a few months after Lee opened the Beijing office, the company announced it would be introducing a new version of its search engine for the Chinese market. Google’s representatives explained that in order to obey China’s censorship laws, the company had agreed to remove any websites disapproved of by the Chinese government from the search results it would display. For example, any site that promoted the Falun Gong, a government-banned spiritual movement, would not be displayed. Similarly (and ironically) sites promoting free speech in China would not be displayed, and there would be no mention of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. As one Western reporter noted, “If you search for ‘Tibet’ or ‘Falun Gong’ most anywhere in the world on google.com, you’ll find thousands of blog entries, news items, and chat rooms on Chinese repression. Do the same search inside China on google.cn, and most, if not all, of these links will be gone. Google will have erased them completely” (Thompson, 2006).

Google’s decision didn’t go over well in the United States. In February 2006, company executives were called into congressional hearings and compared to Nazi collaborators. The company’s stock fell, and protesters waved placards outside the company’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. Google wasn’t the only American technology company to run aground in China during those months, nor was it the worst offender. However, Google’s executives were supposed to be different; given their lofty motto, they were supposed to be a cut above the rest. When the company went public in 2004, its founders wrote in the company’s official filing for the US Securities and Exchange Commission that Google is “a company that is trustworthy and interested in the public good.” Now, politicians and the public were asking how Google could balance that with making nice with a repressive Chinese regime and the Communist Party behind it (Page & Brin, 2004). One exchange between Rep. Tom Lantos (D-CA) and Google Vice President Elliot Schrage went like this:

Lantos:

You have nothing to be ashamed of?

Schrage:

I am not ashamed of it, and I am not proud of it…We have taken a path, we have begun on a path, we have done a path that…will ultimately benefit all the users in China. If we determined, congressman, as a result of changing circumstances or as a result of the implementation of the Google.cn program that we are not achieving those results then we will assess our performance, our ability to achieve those goals, and whether to remain in the market (McCullagh, 2006).

See the video “Google on Operating inside China” at http://news.cnet.com/1606-2-6040114.html. In the video, Schrage, the vice president for corporate communications and public affairs, discusses Google’s competitive situation in China. Rep. James Leach (R-IA) subsequently accuses Google of becoming a servant of the Chinese government.

Google Ends Censorship in China

In 2010, Google announced that it was no longer willing to censor search results on its Chinese service. The world’s leading search engine said the decision followed a cyberattack that it believes was aimed at gathering information on Chinese human rights activists (Vascellaro, Dean, & Gorman, 2010). Google also cited the Chinese government’s restrictions on the Internet in China during 2009 (Branigan, 2010). Google’s announcement led to speculation whether Google would close its offices in China or would close Google.cn. Human rights activists cheered Google’s move, while business pundits speculated on the possibly huge financial costs that would result from losing access to one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing consumer markets.

In an announcement provided to the US Securities and Exchange Commission, Google’s founders summarized their stance and the motivation for it. Below are excerpts from Google Chief Legal Officer David Drummond’s announcement on January 12, 2010 (Drummond, 2010).

Like many other well-known organizations, we face cyberattacks of varying degrees on a regular basis. In mid-December, we detected a highly sophisticated and targeted attack on our corporate infrastructure originating from China, resulting in the theft of intellectual property from Google. However, it soon became clear that what at first appeared to be solely a security incident—albeit a significant one—was something quite different.

First, this attack was not just on Google. As part of our investigation, we have discovered that at least twenty other large companies from a wide range of businesses—including the Internet, finance, technology, media, and chemical sectors—have been similarly targeted. We are currently in the process of notifying those companies, and we are also working with the relevant US authorities.

Second, we have evidence to suggest that a primary goal of the attackers was accessing the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists. Based on our investigation to date, we believe their attack did not achieve that objective. Only two Gmail accounts appear to have been accessed, and that activity was limited to account information (such as the date the account was created) and subject line, rather than the content of emails themselves.

Third, as part of this investigation but independent of the attack on Google, we have discovered that the accounts of dozens of US-, China- and Europe-based Gmail users who are advocates of human rights in China appear to have been routinely accessed by third parties. These accounts have not been accessed through any security breach at Google, but most likely via phishing scams or malware placed on the users’ computers.

We have taken the unusual step of sharing information about these attacks with a broad audience, not just because of the security and human rights implications of what we have unearthed, but also because this information goes to the heart of a much bigger global debate about freedom of speech. In the last two decades, China’s economic reform programs and its citizens’ entrepreneurial flair have lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese people out of poverty. Indeed, this great nation is at the heart of much economic progress and development in the world today.

The decision to review our business operations in China has been incredibly hard, and we know that it will have potentially far-reaching consequences. We want to make clear that this move was driven by our executives in the United States, without the knowledge or involvement of our employees in China who have worked incredibly hard to make Google.cn the success it is today. We are committed to working responsibly to resolve the very difficult issues raised.

The Chinese government’s first response to Google’s announcement was simply that it was “seeking more information” (Branigan, 2010). In the interim, Google “shut down its censored Chinese version and gave mainlanders an uncensored search engine in simplified Chinese, delivered from its servers in Hong Kong” (McCracken, 2010). Like most firms that venture out of their home markets, Google’s experiences in China and other foreign markets have driven the company to reassess how it does business in countries with distinctly different laws.

Opening Case Exercises

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Can Google afford not to do business in China?

- Which stakeholders would be affected by Google’s managers’ possible decision to shut down its China operations? How would they be affected? What trade-offs would Google be making?

- Should Google’s managers be surprised by the China predicament?

References

Branigan, T., “Google Challenge to China over Censorship,” Guardian, January 13, 2010, accessed January 25, 2010, http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/jan/13/google-china-censorship-battle.

Branigan, T., “Google to End Censorship in China over Cyber Attacks,” Guardian, January 13, 2010, accessed November 12, 2010, http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/jan/12/google-china-ends-censorship.

Drummond, D>, “A New Approach to China,” Official Google Blog, January 12, 2010, accessed January 25, 2010, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2010/01/new-approach-to-china.html.

McCracken, H., “Google’s Bold China Move,” PCWorld, March 23, 2010, accessed November 12, 2010, http://www.pcworld.com/article/192130/googles_bold_china_move.html.

McCullagh, D., “Congressman Quizzes Net Companies on Shame,” CNET, February 15, 2006, accessed January 25, 2010, http://news.cnet.com/Congressman-quizzes-Net-companies-on-shame/2100-1028_3-6040250.html.

Oates, J., “Chinese Government Censors Online Games,” Register, June 1, 2004, accessed November 12, 2010, http://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/06/01/china_bans_games.

Page, L. and Sergey Brin, “2005 Founders’ Letter,” Google Investor Relations, December 31, 2005, accessed October 25, 2010, http://investor.google.com/corporate/2005/founders-letter.html.

Sherriff, L., “Google Goes to China,” Register, May 11, 2005, accessed January 25, 2010, http://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/05/11/google_china.

Thompson, C., “Google’s China Problem (and China’s Google Problem),” New York Times, April 23, 2006, accessed January 25, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/magazine/23google.html.

Vascellaro, J. E., Jason Dean, and Siobhan Gorman, “Google Warns of China Exit over Hacking,” January 13, 2010, accessed November 12, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB126333757451026659.html#ixzz157TXi4FV.