8.1 Global Strategic Choices

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the rationale and motivations for international expansion.

- Understand the importance of international due diligence.

- Recognize the role of regional differences, consumer preferences, and industry dynamics.

The Why, Where, and How of International Expansion

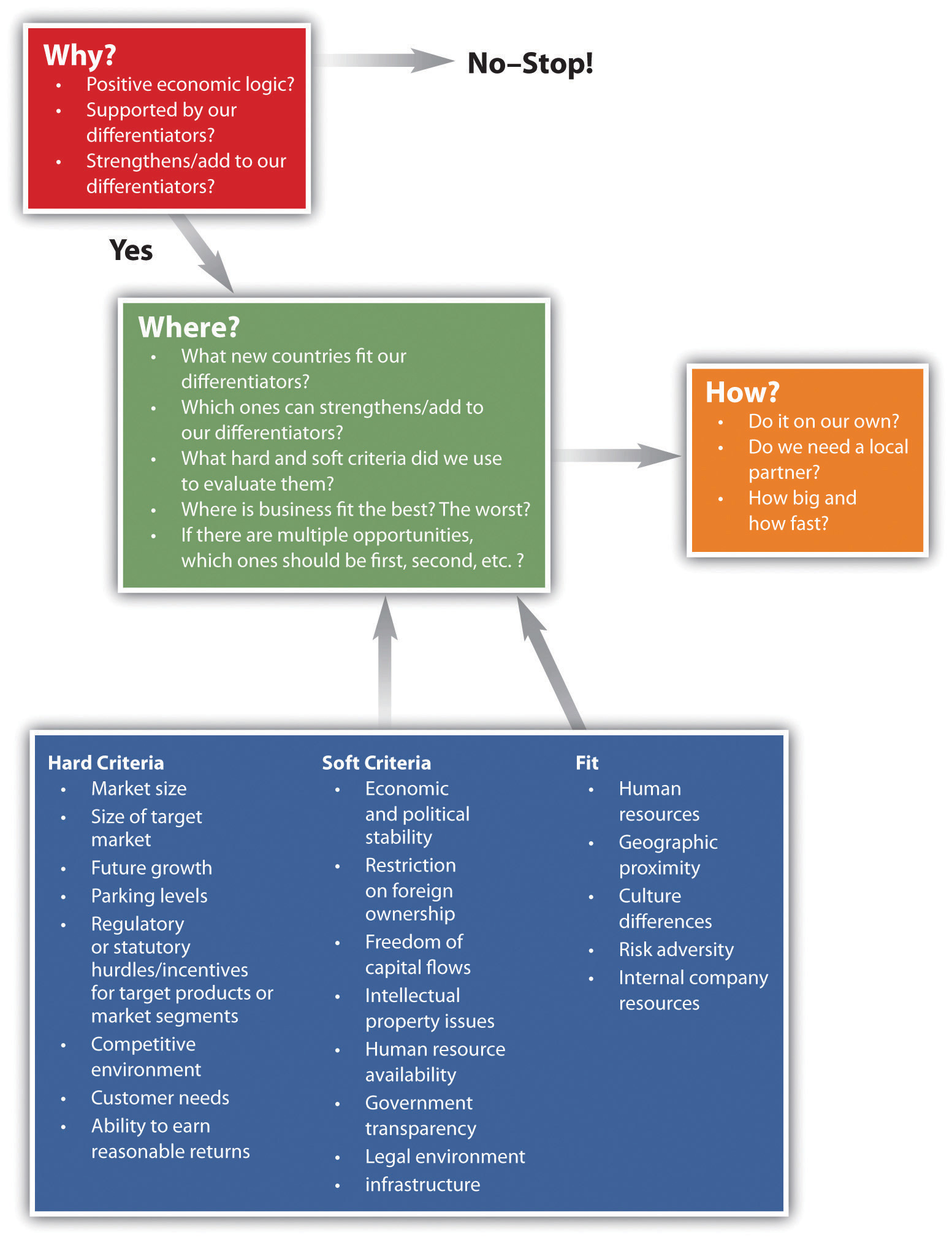

The allure of global markets can be mesmerizing. Companies that operate in highly competitive or nearly saturated markets at home, for instance, are drawn to look overseas for expansion. But overseas expansion is not a decision to be made lightly, and managers must ask themselves whether the expansion will create real value for shareholders. Companies can easily underestimate the costs of entering new markets if they are not familiar with the new regions and the business practices common within the new regions. For some companies, a misstep in a foreign market can put their entire operations in jeopardy, as happened to French retailer Carrefour after their failed entry into Chile, which you’ll see later in this section. In this section, as summarized in the following figure, you will learn about the rationale for international expansion and then how to analyze and evaluate markets for international expansion.

Rationale for International Expansion

Companies embark on an expansion strategy for one or more of the following reasons:

- To improve the cost-effectiveness of their operations

- To expand into new markets for new customers

- To follow global customers

For example, US chemical firm DuPont, Brazilian aerospace conglomerate Embraer, and Finnish mobile-phone maker Nokia are all investing in China to gain new customers. Schneider Logistics, in contrast, initially entered a new market, Germany, not to get new customers but to retain existing customers who needed a third-party logistics firm in Germany. Thus, Schneider followed its customers to Germany. Other companies, like microprocessor maker Intel, are building manufacturing facilities in China to take advantage of the less costly and increasingly sophisticated production capabilities. For example, Intel built a semiconductor manufacturing plant in Dalian, China, for $2.5 billion, whereas a similar state-of-the-art microprocessor plant in the United States can cost $5 billion.[1] Intel has also built plants in Chengdu and Shanghai, China, and in other Asian countries (Vietnam and Malaysia) to take advantage of lower costs.

Planning for International Expansion

As companies look for growth in new areas of the world, they typically prioritize which countries to enter. Because many markets look appealing due to their market size or low-cost production, it is important for firms to prioritize which countries to enter first and to evaluate each country’s relative merits. For example, some markets may be smaller in size, but their strategic complexity is lower, which may make them easier to enter and easier from an operations point of view. Sometimes there are even substantial regional differences within a given country, so careful investigation, research, and planning are important to do before entry.

International Market Due Diligence

International market due diligence involves analyzing foreign markets for their potential size, accessibility, cost of operations, and buyer needs and practices to aid the company in deciding whether to invest in entering that market. Market due diligence relies on using not just published research on the markets but also interviews with potential customers and industry experts. A systematic analysis needs to be done, using tools like PESTEL and CAGE, which will be described in Section 8.2 “PESTEL, Globalization, and Importing” and Section 8.4 “CAGE Analysis”, respectively. In this section, we begin with an overview.

Evaluating whether to enter a new market is like peeling an onion—there are many layers. For example, when evaluating whether to enter China, the advantage most people see immediately is its large market size. Further analysis shows that the majority of people in that market can’t afford US products, however. But even deeper analysis shows that while many Chinese are poor, the number of people who can afford consumer products is increasing (Kleiner, 2010).

Regional Differences

The next part of due diligence is to understand the regional differences within the country and to not view the country as a monolith. For example, although companies are dazzled by China’s large market size, deeper analysis shows that 70 percent of the population lives in rural areas. This presents distribution challenges given China’s vast distances. In addition, consumers in different regions speak different dialects and have different tastes in food. Finally, the purchasing power of consumers varies in the different cities. City dwellers in Shanghai and Tianjin can afford higher prices than villagers in a western province.

Let’s look at a specific example. To achieve the dual goals of reducing operations costs and being closer to a new market of customers, for instance, numerous high-tech companies identify Malaysia as an attractive country to enter. Malaysia is a relatively inexpensive country and the population’s English skills are good, which makes it attractive both for finding local labor and for selling products. But even in a small country like Malaysia, there are regional differences. Companies may be tempted to set up operations in the capital city, Kuala Lumpur, but doing a thorough due diligence reveals that the costs in Kuala Lumpur are rising rapidly. If current trends continue, Kuala Lumpur will be as expensive as London in five years. Therefore, firms seeking primarily a lower-cost advantage would do better to locate to another city in Malaysia, such as Penang, which has many of the same advantages as Kuala Lumpur but does not have its rising costs (Chamania, Mehta, & Sehgal, 2010).

Understanding Local Consumers

Entering a market means understanding the local consumers and what they look for when making a purchase decision. In some markets, price is an important issue. In other markets, such as Japan, consumers pay more attention to details—such as the quality of products and the design and presentation of the product or retail surroundings—than they do to price. The Japanese demand for perfect products means that firms entering Japan might have to spend a lot on quality management. Moreover, real-estate costs are high in Japan, as are freight costs such as fuel and highway charges. In addition, space is limited at retail stores and stockyards, which means that stores can’t hold much inventory, making replenishment of products a challenge. Therefore, when entering a new market, it’s vital for firms to perform full, detailed market research in order to understand the market conditions and take measures to account for them.

How to Learn the Needs of a New Foreign Market

The best way for a company to learn the needs of a new foreign market is to deploy people to immerse themselves in that market. Larger companies, like Intel, employ ethnographers and sociologists to spend months in emerging markets, living in local communities and seeking to understand the latent, unarticulated needs of local consumers. For example, Dr. Genevieve Bell, one of Intel’s anthropologists, traveled extensively across China, observing people in their homes to find out how they use technology and what they want from it. Intel then used her insights to shape its pricing strategies and its partnership plans for the Chinese consumer market (Radjou, 2009).

Differentiation and Capability

When entering a new market, companies also need to think critically about how their products and services will be different from what competitors are already offering in the market so that the new offering provides customers value. Companies trying to penetrate a new market must be sure to have some proof that they can deliver to the new market; this proof could be evidence that they have spoken with potential customers and are connected to the market.[2] Related to firm capability, another factor for firms to consider when evaluting which country to enter is that of “corporate fit.” Corporate fit is the degree to which the company’s existing practices, resources and capabilties fit the new market. For example, a company accustomed to operating within a detailed, unbiased legal environment would not find a good corporate fit in China because of the current vagaries of Chinese contract law (Wingard, 2011). Whereas a low corporate fit doesn’t preclude expanding into that country, it does signal that additional resources or caution may be necessary. Two typical dimensions of corporate fit are human resources practices and the firm’s risk tolerance.

Did You Know?

Over the years 2005–09, the number of Global 500 companies headquartered in BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) increased significantly. China grew from 8 headquarters to 43, India doubled from 5 to 10, Brazil rose from 5 to 9, and Russia went from 4 to 6. The United States still leads with 181 company headquarters, but it’s down from 219 in 2005 (Meister & Willyerd, 2009).

Industry Dynamics

In some cases, the decision to enter a new market will depend on the specific circumstances of the industry in which the company operates. For example, companies that help build infrastructure need to enter countries where the government or large companies have a lot of capital, because infrastructure projects are so expensive. The president of Spanish infrastructure company Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas said, “We focus on those countries where there is more money and there is a gap in the infrastructure,” such as China, Singapore, the United States, and Algeria.[3]

Political stability, legal security, and the “rule of law”—the presence of and adherence to laws related to business contracts, for example—are important considerations prior to market entry regardless of which industry a company is in. Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas learned this the hard way and ended up leaving some countries it had entered. The company’s president, Baldomero Falcones, explained, “When you decide whether or not to invest, one factor to take into account is the rule of law. Our ethical code was considered hard to understand in some countries, so we decided to leave during the early stages of the investment.”[4]

Ethics in Action

Companies based in China are entering Australia and Africa, primarily to gain access to raw materials. Trade between China and Africa grew an average of 30 percent in the decade up to 2010, reaching $115 billion that year (Redfern, 2011). Chinese companies operate in Zambia (mining coal), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (mining cobalt), and Angola (drilling for oil). To get countries to agree to the deals, China had to agree to build new infrastructure, such as roads, railways, hospitals, and schools. Some economists, such as Dambisa Moyo, who wrote Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa, believe that the way to help developing countries like those in Africa is not through aid but through trade. Moyo argues that long-term charity is degrading. She advocates business investments and setting up enterprises that employ local workers. Ecobank CEO Arnold Ekpe (whose bank employs 11,000 people in twenty-six African states) says the Chinese look at Africa differently than the West does: “[The Chinese] are not setting out to do good,” he says. “They are setting out to do business. It’s actually much less demeaning” (Perry, 2009). Deborah Brautigam, associate professor at the American University’s International Development Program, agrees. In her book, The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, she says, “The Chinese understand something very fundamental about state building: new states need to build buildings and dignity, not simply strive to end poverty” (Bloomfield, 2010).

Steps and Missteps in International Expansion

Let’s look at an example of the steps—as well as the missteps—in international expansion. American retailers entered the Chilean market in the mid- to late 1990s. They chose Chile as the market to enter because of the country’s strong economy, the advanced level of the Chilean retail sector, and the free trade agreements signed by Chile. From that standpoint, their due diligence was accurate, but it didn’t go far enough, as we’ll see.

Retailer JCPenney entered Chile in 1995, opening two stores. French retailer Carrefour also entered Chile, in 1998. Neither company entered through an alliance with a local retailer. Both companies were forced to close their Chilean operations due to the losses they were incurring. Analysis by the Aldolfo Ibáñez University in Chile explained the reasons behind the failures: the managers of these companies were not able to connect with the local market, nor did they understand the variables that affected their businesses in Chile.[5] Specifically, the Chilean retailing market was advanced, but it was also very competitive. The new entrants (JCPenney and Carrefour) didn’t realize that the existing major local retailers had their own banks and offered banking services at their retail stores, which was a major reason for their profitability. The outsiders assumed that profitability in this sector was based solely on retail sales. They missed the importance of the bank ties. Another typical mistake that companies make is to assume that a new market has no competition just because the company’s traditional competitors aren’t in that market.

Now let’s continue with the example and watch native Chilean retailers enter a market new to them: Peru.

The Chilean retailers were successful in their own markets but wanted to expand beyond their borders in order to get new customers in new markets. The Chilean retailers chose to enter Peru, which had the same language.

The Peruvian retailing market was not advanced, and it did not offer credit to customers. The Chileans entered the market through partnership with local Peruvian firms, and they introduced the concept of credit cards, which was an innovation in the poorly developed Peruvian market. Entering through a domestic partner helped the Chileans because it eliminated hostility and made the investment process easier. Offering the innovation of credit cards made the Chilean retailers distinctive and offered an advantage over the local offerings.[6]

Key Takeaways

- Companies embark on an expansion strategy for one or more of the following reasons: (1) to improve the cost-effectiveness of their operations, (2) to expand into new markets for new customers, and (3) to follow global customers.

- Planning for international expansion involves doing a thorough due diligence on the potential markets into which the country is considering expanding. This includes understanding the regional differences within markets, the needs of local customers, and the firm’s own capabilities in relation to the dynamics of the industry.

- Common mistakes that firms make when entering a new market include not doing thorough research prior to entry, not understanding the competition, and not offering a truly targeted value proposition for buyers in the new market.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What are some of the common motivators for companies embarking on international expansion?

- Why is international market due diligence important?

- What are some ways in which a company can learn about the needs of local buyers in a new international market?

- Discuss the meaning of “corporate fit” in relation to international market expansion.

- Name two common mistakes firms make when expanding internationally

References

Bloomfield, S., “China in Africa: Give and Take,” Emerging Markets, May 27, 2010, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.emergingmarkets.org/Article/2580082/CHINA-IN-AFRICA-Give-and-take.html.

Chamania, A., Heral Mehta, and Vikas Sehgal, “Five Factors for Finding the Right Site,” Strategy and Business, November 23, 2010, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/10403?gko=e029a.

Kleiner, A., “Getting China Right,” Strategy and Business, March 22, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/00026?pg=al.

Meister, J. and Karie Willyerd, The 2020 Workplace (New York: HarperBusiness, 2010), 22, citing “FT500 2009,” Financial Times, accessed November 27, 2009, http://www.ft.com/reports/ft500-2009.

Perry, A., “Africa, Business Destination,” Time, March 12, 2009, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1884779_1884782_1884769,00.html#ixzz1DwbdOXvs.

Radjou, N., “R&D 2.0: Fewer Engineers, More Anthropologists,” Harvard Business Review (blog), June 10, 2009, accessed January 2, 2011, http://blogs.hbr.org/radjou/2009/06/rd-20-fewer-engineers-more-ant.html.

Redfern, P., “Africa: Trade between China and Continent at U.S.$115 Billion a Year,” Daily Nation, February 11, 2011, accessed February 14, 2011, http://allafrica.com/stories/201102140779.html.

Wingard, C., “Ensuring Value Creation through International Expansion,” L.E.K. Consulting Executive Insights 5, no. 3, accessed January 15, 2011, http://www.lek.com/sites/default/files/Volume_V_Issue_3.pdf.

- “2011 Global R&D Funding Forecast,” R&D Magazine, December 2010, accessed January 2, 2011, http://www.rdmag.com/tags/publications/global-r-and-d-funding-forecast. ↵

- “How We Do It: Strategic Tests from Four Senior Executives,” McKinsey Quarterly, January 2011, accessed January 22, 2011, https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/PDFDownload.aspx?ar=2712&srid=27. ↵

- “Practical Advice for Companies Betting on a Strategy of Globalization,” Knowledge@Wharton, January 12, 2011, accessed February 5, 2011, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2541. ↵

- “Practical Advice for Companies Betting on a Strategy of Globalization,” Knowledge@Wharton, January 12, 2011, accessed February 5, 2011, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2541. ↵

- “The Globalization of Chilean Retailing,” Knowledge@Wharton, December 12, 2007, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.wharton.universia.net/index.cfm?fa=viewfeature&id=1450&language=english. ↵

- "The Globalization of Chilean Retailing,” Knowledge@Wharton, December 12, 2007, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.wharton.universia.net/index.cfm?fa=viewfeature&id=1450&language=english. ↵