13.3 How to Organize and Where to Locate Research and Development Activities

Learning Objectives

- Understand two main ways in which to organize research and development (R&D) activities in a global organization.

- Be able to describe two factors to consider when deciding where in the world to locate R&D activities.

- Know what an innovation hub is and how governments can influence innovation.

How to Organize R&D Activities

The flattening world is putting more pressure on corporate research and development (R&D) to come up with new products and services in less time and at lower cost. As a result, new models for how a company should organize its R&D activities have emerged. The traditional model of having one central R&D center located in the United States is being replaced by having a network of smaller R&D centers located in various parts of the world. The reasons for this dispersion of R&D activities are to tap talent around the world, to lower costs, and to be better able to develop new products and services tailored to new country markets.

When designing the R&D network, companies need to make sure that all centers use the same communication and information systems platform so that team members can communicate regardless of where they are. Some companies also offer financial and promotion incentives to encourage employees to work in different locations (Goldbrunner, Doz, & Wilson, 2006).

The director of HP Labs, Prith Banerjee, explains the benefit and rationale for locating R&D activities in new-market countries in order to innovate more effectively for those markets. Today, HP Labs is located in seven different regions around the world, including India, China, Russia, and Israel. One reason for being in India, besides lower labor costs, is to tap the talent in India and their knowledge of local needs.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

The mission of HP Labs India, Banerjee says, is innovation for the next billion customers: “I strongly believe that it is not very easy for researchers sitting in Palo Alto to imagine the problems for the billion people in India, the vegetable vendors in India. What kind of cell phones, what kind of PDA devices would they need to solve their day-to-day problems? Sitting here in Palo Alto, you imagine that the whole world is developed, and it’s not. So the researchers in India are actually working on precisely those problems.”[1]

One of the challenges of a distributed global network of R&D centers is managing employees located in different countries. Booz & Company surveyed R&D leaders in 186 companies in nineteen nations to ask them their most pressing R&D challenges. The three top challenges executives listed were (1) how to assess the value of a new idea, (2) how to encourage collaboration across geographical locations and functions, and (3) managing the complexity of global R&D projects (Goldbrunner, Doz, & Wilson, 2006). One way that large multinationals manage the challenge of globally distributed innovation activities is through specially trained innovation teams. For example, Whirlpool has devised a way to help encourage and share innovation across a globally distributed enterprise. Specifically, Whirlpool designates “i-mentors” and trains them in innovation and deploys them throughout the organization to identify promising new product ideas (Scanlon, 2009). Similarly, General Mills has two “innovation squads” to harvest ideas from outside and inside the company, respectively. The cross-functional squads consist of six to eight company veterans with between fifteen and twenty-five years of experience. These people hunt for good business ideas and present them to division heads. The squads also give their top-ten ideas to the company chairman once a quarter. For example, one squad found a patent that had been donated to a university. The patent pertained to a new method for encapsulating calcium. The squad converted it into a very successful new product line of orange juice with added calcium that doesn’t taste chalky (Erickson, 2009; MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, 2007).

Did You Know?

Between 1975 and 2005, the percentage of R&D sites located outside the markets of their corporate headquarters has risen from 45 percent to 66 percent (Goldbrunner, Doz, & Wilson, 2006).

Deciding Where to Locate R&D Activities

As we saw in the above example, HP is locating R&D labs in the countries for which it wants to develop new products. Another strategy is to locate the R&D center in a location known to be an innovation hub.

The concept of an innovation hub is based on Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter’s concept of clusters, which he defined in his book The Competitive Advantage of Nations. A cluster is defined as “a geographic concentration of business initiatives, suppliers and associated institutions in a particular field” (Bertolin, 2010). This particular model of location advantage is summarized in Figure 13.1 “Determinants of Location Advantages”. For example, Silicon Valley in California is a cluster for technology companies that have located (or were founded) there. The partnerships and cross-pollination of ideas among the companies created new high-tech businesses whose success in turn brought venture capitalists (VCs) there. VCs looked for new ideas to fund, which led to more high-tech start-ups, thus stimulating even further innovation and new business creation.

Strategy consulting firm McKinsey & Company partnered with the World Economic Forum to evaluate what makes a given region an innovation hub. McKinsey analyzed 700 variables, including business environment, government and regulation, human capital, infrastructure, and local demand (Andonian, Loos, & Pires, 2009). An innovation hub includes universities, government research institutes or labs, and corporate R&D centers. The purpose of the collocation is to create a dense social network. Geographic proximity promotes repeated interactions among people and thus builds trust among the people; companies compete intensely with each other but at the same time they learn from each other about changing markets and technologies (Saxenian ,1994).

Innovation hubs usually have a specific industry focus, which can be anything from footwear to technology to life sciences. Let’s take a look at examples that make this concept clearer. Zhongguancun is a technology district in northwestern Beijing known as “the Silicon Valley of China” (Todd, 2010). Within a one-mile area are China’s top two universities, Tsinghua University and Peking University. Also in the area is Tsinghua Science Park and Shanghai Science and Technology Center. American high-tech company EMC located an R&D facility in this area to be in close proximity to the university talent and encourage some of them to work for EMC. EMC located another R&D center in Bangalore, India, in the Marathahalli-area innovation hub that’s home to the R&D centers of IBM, Oracle, HP, Cisco, and Google; it is also home to the India Institute of Management, a university ranked among the top business schools in the world. Cisco’s R&D center in Bangalore has 1,400 employees, and Cisco invested $750 million in R&D in India.[2] Illustrating Banerjee’s point, however, is that despite all the high-tech companies in the Bangalore area, employees still have to stop their cars for cattle crossing the highway (Todd, 2010).

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 2.0.

The single common factor that drives innovation across all sectors is the availability of a well-qualified talent pool. Talent attracts talent, creating a reinforcing success cycle. People go to work where the work is exciting. If one location has a concentration of R&D labs, universities, and government research facilities, high-caliber people will be attracted to that location.

Hubs are known for the cross-pollination of ideas that takes place when employees of one firm talk with employees of another simply because of their proximity and frequenting the same local restaurants, events, or transportation stops. A specific phenomenon that occurs with this proximity is knowledge spillover. That is, knowledge can “spill over” as locals talk with one another; through those conversations, employees are more likely to understand each other’s innovations and build on them. For example, Adam Jaffe and his colleagues analyzed the prior patents that a firm cited when applying for a new patent (Jaffe, Trajtenberg, & Henderson). Jaffe and his colleagues found that, after controlling for other factors, the cited patents were five to ten times more likely to come from other firms in the same metropolitan area. People were casually sharing and building on each other’s ideas. Jaffe’s finding also explains why it’s harder to take advantage of foreign countries’ knowledge if one is not located there: “culture geography and secrecy make knowledge harder to diffuse across international borders” (Brynjolfsson & Saunders, 2010).

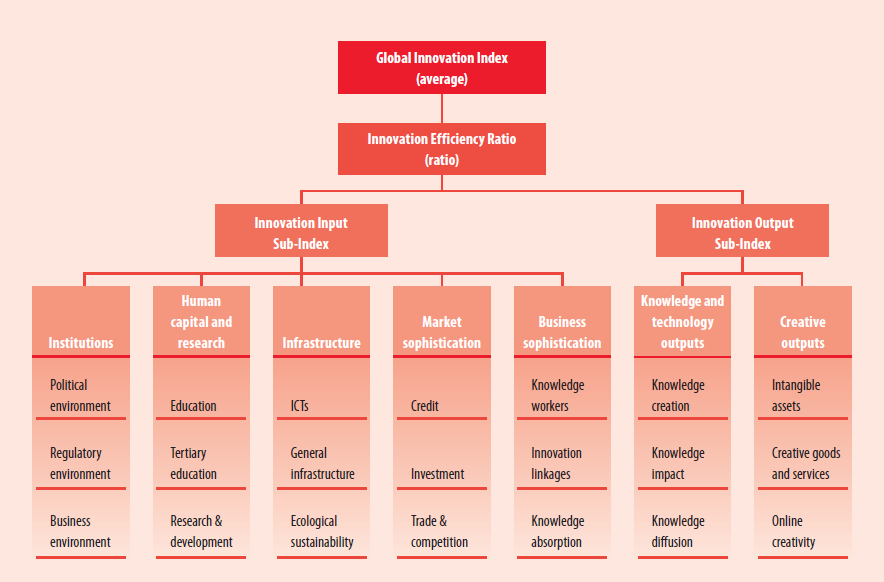

Below is a graphic from the Global Innovation Index. The graphic shows the main enablers that encourage innovation to take place in a given country. These enablers are Human Capacity, General and ICT (information and communication technology) Infrastructure, Market Sophistication, and Business Sophistication. On the right-hand side are the outputs of innovation—namely, scientific papers, patents, and new products and creative works. Companies evaluate the following things when choosing among countries in which to locate R&D facilities:

- A nation’s institutions (the political and regulatory environment)

- A nation’s investment in education

- A nation’s ICT infrastructure

- The sophistication of the market (access to investors and credit)

- Business sophistication (the innovation ecosystem and openness to competition)

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 4.0.

Key Takeaways

- In the past, companies centralized R&D activities into one R&D center located in the same country as the company’s headquarters. Now, that model is being replaced by a network of R&D clusters located in innovation hubs in the countries where a company hopes to grow its business.

- Innovation hubs are geographic locations that have universities, research labs, and corporate R&D centers clustered together. Proximity attracts the best workers and stimulates innovation through the cross-pollination of ideas. Employees are exposed to new ideas, and knowledge “spills over” during the everyday interactions of employees, university professors, and students.

- Countries and regions vary systematically in their levels of innovation, but governments can encourage innovation by supporting the pillars that enable innovation—namely, Institutions, Human Capacity, General and ICT (information and communication technology) Infrastructure, Market Sophistication, and Business Sophistication. The Global Innovation Index shows the level of innovation of any country.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Why might the level of innovation vary across countries and regions?

- What factors would you examine when deciding where to locate an R&D center?

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of organizing corporate R&D into a network of globally distributed R&D centers.

- How might governments or companies go about encouraging the creation of innovation hubs in a specific region?

- Do you think that communication technologies enabled by the Internet will influence knowledge spillover? Why or why not?

References

Andonian, A., Christoph Loos, and Luiz Pires, “Building an Innovation Nation,” McKinsey & Company: What Matters, March 4, 2009, accessed February 24, 2011, http://whatmatters.mckinseydigital.com/innovation/building-an-innovation-nation.

Bertolin, J. A., “Convoy Model: The Dynamic Perspective of Porter’s Cluster Model,” Innovation Management, December 8, 2010, accessed March 10, 2011, http://www.innovationmanagement.se/2010/12/08/convoy-model-the-dynamic-perspective-of-porters-cluster-model.

Brynjolfsson, E. and Adam Saunders, Wired for Innovation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 99.

Erickson, P., “Innovating on Innovation” (keynote presentation at the Front End of Innovation Conference, Boston, MA, May 2009).

Goldbrunner, T., Yves Doz, and Keeley Wilson, “The Well-Designed Global R&D Network,” Strategy and Business, May 30, 2006, accessed January 10, 2011, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/06217?gko=0a6cc.

Jaffe, A., Manuel Trajtenberg, and Rebecca Henderson, “Geographic Localization of Knowledge Spillovers as Evidenced by Patent Citations,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, no. 3: 577–98.

MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, “Future Capabilities in the Supply Chain” (presentation in Cambridge, MA, May 8, 2007).

Saxenian, A., Regional Advantage (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 2–3, 161.

Scanlon, J., “How Whirlpool Puts New Ideas through the Wringer,” BusinessWeek, August 3, 2009, accessed January 17, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/aug2009/id2009083_452757.htm.

Todd, S., Innovate with Global Influence (Bangor, ME: Booklocker.com, 2010), 9.

- “Wedding Innovation with Business Value: An Interview with the Director of HP Labs Prith Banerjee,” McKinsey Quarterly, February 1, 2010, accessed January 2, 2011, https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Strategy/Innovation/Wedding_innovation_with_business_value_An_interview_with_the_director _of_HP_Labs_2522. ↵

- “The New Geography of Global Innovation,” Innovation Management, September 20, 2010, accessed February 26, 2011, http://www.innovationmanagement.se/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/The-new-geography-of-global-innovation.pdf. ↵