12.4 The Roles of Pay Structure and Pay for Performance

Learning Objectives

- Explain the factors to be considered when setting pay levels.

- Understand the value of pay for performance plans.

- Discuss the challenges of individual versus team-based pay.

Compensation Design Issues for Global Firms

Pay can be thought of in terms of the “total reward” that includes an individual’s base salary, variable pay, share ownership, and other benefits. A bonus, for example, is a form of variable pay. A bonus is a one-time cash payment, often awarded for exceptional performance. Providing employees with an annual statement of all the benefits they receive can help them understand the full value of what they are getting (Anderson, 2007).

There are five areas that global firms must manage when designing their compensation strategy. The first involves setting up a worldwide compensation system. What this means is that the firm is coordinating each country’s compensation in such a way that the overall collection of countries operates as a system. Management, for instance, will have decided which features of the system to standardize and which ones to adapt to local customs, cultures, and practices. The second part of the strategy involves decisions about how to compensate third-country nationals. A third-country national (TCN) is an individual who is a citizen of neither the United States nor the host country and who is hired by the US government or a government-sanctioned contractor to perform work in the host country. TCNs most often perform work on government contracts in the role of a private military contractor. The term can also be applied to foreign workers employed in private industry in the Arab Gulf region (e.g., Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia), in which it’s common to outsource work to noncitizens.

The last three areas of compensation strategy relate to questions about international benefits and related taxes, pension plans, and stock-ownership plans. With expatriates, for instance, pay is but a small percentage of total compensation. A typical expatriate package will include the following: (Chynoweth, 2010)

- A cost-of-living allowance to protect the employee’s purchasing power (the goal is equalization, not a bonus)

- A mobility premium of 5 percent to 15 percent of gross salary

- A hardship allowance of up to 30 percent for employees moving to difficult areas

- Reasonable costs for moving furniture

- Schooling costs for children between four and eighteen years of age

- Family support to cover language and cultural training and help for the spouse to find work

- A one-off payment, usually of one month’s salary, to cover miscellaneous expenses

Did You Know?

As firms enter emerging markets to take advantage of the tremendous growth opportunities there, they are finding that they need to develop in-country talent rather than just send expatriates. The knowledge that in-country managers have of the local culture and the sheer numbers of employees that will be needed to staff local operations drive managers to hire locally. Senior HR professionals need to ask themselves the following questions:

- How many of our current executives live in the countries where we do business?

- Is the number of native executives proportional to the revenue of those countries?

- How many of our senior executive team are from countries where we are experiencing growth?

It takes time to build talent in emerging markets, where the talent pool may be less experienced, so HR managers need to plan ahead.

Pay System Elements

As summarized in Table 12.1 “Elements of a Pay System”, pay can take the form of direct or indirect compensation. Nonmonetary pay can include any benefit an employee receives from an employer or job that doesn’t involve tangible value. This includes career and social rewards—job security, flexible hours, opportunities for growth, praise and recognition, task enjoyment, and friendships. Direct pay is an employee’s base wage. It can be an annual salary, hourly wage, or any performance-based pay that an employee receives, such as profit-sharing bonuses.

Table 12.1 Elements of a Pay System

| Nonmonetary pay | Benefits that don’t involve tangible value |

| Direct pay | Employee’s base wage |

| Indirect pay | Everything from legally required programs to health insurance, retirement, housing, etc. |

| Basic pay | Cash wages paid to the employee. Because paying a wage is a standard practice, the competitive advantage can only come by paying a higher amount. |

| Incentive pay | A bonus paid when specified performance objectives are met. May inspire employees to set and achieve a higher performance level and is an excellent motivator to accomplish firm goals. |

| Stock options | A right to buy a piece of the business that may be given to an employee to reward excellent service. An employee who owns a share of the business is far more likely to go the extra mile for the operation. |

| Bonuses | Gifts given occasionally to reward exceptional performance or for special occasions. Bonuses can show that an employer appreciates its employees and ensures that good performance or special events are rewarded. |

Source: Mason Carpenter, Talya Bauer, and Berrin Erdogan, Principles of Management, 2009), accessed January 5, 2011.

Indirect compensation is far more varied, including everything from social security and health insurance to retirement programs, paid leave, child care, and housing. US law requires some indirect-compensation elements (e.g., social security, unemployment, and disability payments). Other indirect elements are up to the employer and can serve as excellent ways to provide benefits to both the employees and the employer. For example, a working parent may take a lower-paying job with flexible hours that will allow him to be home when the children get home from school. A recent graduate may be looking for stable work and an affordable place to live. Both of these individuals have different needs and, therefore, would appreciate different compensation elements.

Setting Pay Levels

When setting pay levels for positions, managers should make sure that the pay level is fair relative to what other employees in the position are being paid. Part of the pay level is determined by similar pay levels at other companies. If your company pays substantially less than others, it’s going to be the last choice of employment—unless it offers something overwhelmingly positive to offset the low pay, such as flexible hours or a fun, congenial work atmosphere. Besides these external factors, companies conduct a job evaluation to determine the internal value of the job—the more vital the job to the company’s success, the higher the pay level. Jobs are often ranked alphabetically—“A” positions are those on which the company’s value depends; “B” positions are somewhat less important in that they don’t deliver as much upside to the company; and “C” positions are those of least importance—in some cases, these are outsourced.

The most vital jobs to one company’s success may not be the same in other companies. For example, information technology companies may put top priority on their software developers and programmers, whereas retailers such as Nordstrom would consider the frontline employees who provide personalized service as the “A” positions. For an airline, pilots would be a “B” job because, although they need to be well trained, investing further in their training is unlikely to increase the airline’s profits. “C” positions for a retailer might include back-office bill processing, while an information technology company might classify customer service as a “C” job.

When setting reward systems, it’s important to pay for what the company actually hopes to achieve. Steve Kerr, a senior advisor and former chief learning officer at Goldman Sachs, talks about the common mistakes that companies make with their reward systems, such as saying they value teamwork but only rewarding individual effort. Similarly, companies say they want innovative thinking or risk taking, but they reward people who “make the numbers” (Kerr, 1995). If companies truly want to achieve what they hope for, they need payment systems aligned with their goals. For example, if retention of star employees is important to your company, reward managers who retain top talent. At PepsiCo, for instance, a third of a manager’s bonus is tied directly to how well the manager did at developing and retaining employees. Tying compensation to retention makes managers accountable (Field & Gordon, 2008).

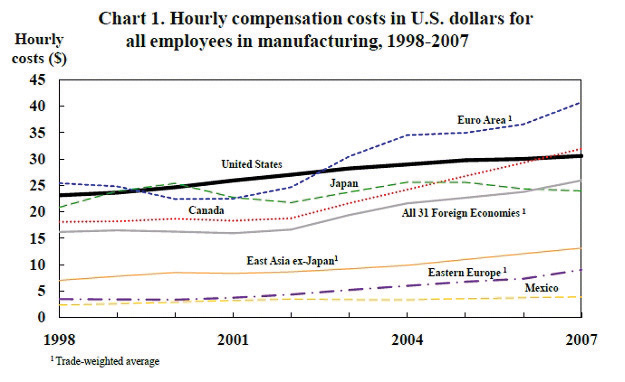

As you can imagine, one of the reasons that firms seek workers in other countries is to take advantage of the low relative cost of labor. As shown in the following figure, the most recent US Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that the United States is among the costliest countries for manufacturing employees, exceeded only by Canada and countries in the Euro Area (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, and Spain).

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “International Comparisons of Hourly Compensation Costs in Manufacturing, 2009,” news release, March 8, 2011, accessed June 3, 2011, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ichcc.pdf.

It’s important to point out, however, that simply because a company locates an operation in a lower-pay market doesn’t necessarily mean that the cost of the operation will be less. For instance, in a 2009 interview Emmanuel Hemmerle, a principal with executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles, noted,

There’s a wrong assumption with regard to China. Headquarters in Japan, in Europe, in the US tend to believe that China, because it’s low cost, should be cheaper in terms of executives’ packages. Nothing is more wrong. In fact, if you want to woo top talent, you’re going to have to pay the right amounts. Often you end up with packages for similar skill sets, similar responsibility, scope, size, everything…that is higher in China than what would be the case with similar counterparts in Europe and the US. And we spend a lot of time coaching companies, especially those that are headquartered overseas, that they need to invest in talent [in much the same way as they would] invest to create a new research center, to create new production facilities in China. They need to invest in the talent. If you want top talent, you’re going to have to pay for it. We’re starting to see some interesting trends. We can start seeing a number of top talents who meet the international best standards, who could compete with their peers in the US or in Europe—and I’m talking about in terms of performance, in terms of skill sets. And probably, we’re going to start seeing more and more of that…I believe that it makes less and less sense to have Westerners, or [expatriates], let’s say, who are compensated twice or three times as much as the local mainland Chinese, while performance is equivalent or sometimes even lower. That will create issues, very serious issues, in your organization. I’m always concerned and worried when a company tells me that they want to localize because they want to drive down costs. There’s a host of reasons that are better reasons than just cost (Chandler, 2009).

As the Heidrick & Struggles example suggests, it’s often a dilemma whether a multinational company should localize or globalize its compensation for the local managers. If they pay them on the basis of global standards, a higher cost will emerge. If not, it will be difficult to retain them. Pay inequity will often lead to a sense of unfairness. You can imagine a local manager asking herself, “Why should I get two or three times less pay even when I deliver a better performance than the expatriates?”

Pay for Performance

As its name implies, pay for performance ties pay directly to an individual’s performance in meeting specific business goals or objectives. Managers (often together with the employees themselves) design performance targets to which the employees will be held accountable. The targets have accompanying metrics that enable employees and managers to track performance. The metrics can be financial indicators, or they can be indirect indicators such as customer satisfaction or speed of development. Pay-for-performance schemes often combine a fixed base salary with a variable pay component (e.g., bonuses or stock options) that varies with the individual’s performance.

Innovative Employee-Recognition Programs

In addition to regular pay structures and systems, companies often create special programs that reward exceptional employee performance. For example, the financial software company Intuit instituted a program called Spotlight. The purpose of Spotlight is to “spotlight performance, innovation and service dedication” (Hoyt, 2009). Unlike regular salaries or year-end bonuses, Spotlight awards can be given on the spot for specific behavior that meets the reward criteria, such as filing a patent, inventing a new product, or meeting a milestone for years of service. Rewards can be cash awards of $500 to $3,000 and can be made by managers without high-level approval. In addition to cash and noncash awards, two Intuit awards feature a trip with $500 in spending money (Mosley, 2008).

Pay Structures for Groups and Teams

So far, we have discussed pay in terms of individual compensation, but many employers also use compensation systems that reward all the organization’s employees as a group or various groups and teams within the organization. Let’s examine some of these less-traditional pay structures.

Gainsharing

Sometimes called profit sharing, gainsharing is a form of pay for performance. In gainsharing, the organization shares the financial gains with employees. Employees receive a portion of the profit achieved from their efforts. How much they receive is determined by their performance against the plan. Here’s how gainsharing works: First, the organization must measure the historical (baseline) performance. Then, if employees help improve the organization’s performance on those measures, they share in the financial rewards achieved. This sharing is typically determined by a formula.

The effectiveness of a gainsharing plan depends on employees seeing a relationship between what they do and how well the organization performs. The larger the organization, the harder it is for employees to see the effects of their work. Therefore, gainsharing plans are more effective in companies with fewer than 1,000 people (Lawler III, 1992). Gainsharing success also requires the company to have good performance metrics in place so that employees can track their process. The gainsharing plan can only be successful if employees believe and see that if they perform better, they will be paid more. The pay should be given as soon as possible after the performance so that the tie between the two is established.

When designing systems to measure performance, realize that performance appraisals need to focus on quantifiable measures. Designing these measures with input from the employees helps make the measures clear and understandable to employees and increases their gainsharing buy-in.

Team-Based Pay

Many managers seek to build teams but face the question of how to motivate all the members to achieve the team’s goals. As a result, team-based pay is becoming increasingly accepted. In 1992, only 3 percent of companies had team-based pay (Flannery, 1996). By 1999, 80 percent of companies had team-based pay (Garvey, 2002). With increasing acceptance and adoption comes different choices and options of how to structure team-based pay. One way is to first identify the type of team you have—parallel, work, project, or partnership—and then choose the pay option that’s most appropriate.

Parallel teams are teams that exist alongside (parallel to) an individual’s daily team. For example, a person may be working in the accounting department but may also be asked to join a team on productivity. Parallel teams usually meet on a part-time rather than a full-time basis and are often interdepartmental and formed to deal with a specific issue. The reward for performance on this team would typically be a merit increase or a recognition award (cash or noncash) for performance on the team.

A project team is another temporary team, but it meets full-time for the life of the project. For example, a team may be formed to develop a new product and then disband when the new product is completed. The pay schemes appropriate for this team include profit sharing, recognition rewards, and stock options. Team members may be asked to evaluate each other’s performance.

A partnership team is formed around a joint venture or strategic alliance. Profit sharing in the venture is the most common pay structure.

Finally, with the work team, all individuals work together daily to accomplish their jobs. Skill-based pay and gainsharing are the payment schemes of choice, with team members evaluating one another’s performance.

Pay Systems that Reward Both Team and Individual Performance

There are two main theories of how to reward employees. Nancy Katz characterized the theories as two opposing camps. The first camp advocates rewarding individual performance, through plans such as commissions-sales schemes and merit-based pay. The claim is that this will increase employees’ energy, drive, willingness to take risks, and task identification. The disadvantages of rewarding individual performance are that employees will cooperate less, that high performers may be resented by others in the corporation, and that low performers may try to undermine top performers (Katz, 1998).

The second camp believes that organizations should reward team performance, without regard for individual accomplishment. This reward system is thought to bring the advantages of increased helping and cooperation, sharing of information and resources, and mutual respect among employees. The disadvantages of team-based reward schemes are that they create a lack of drive, that low performers become free riders, and that high performers may withdraw or become “tough cops.” Free riders are individuals who benefit from a the actions of others without contributing or paying their fair share of the costs. The term can apply to individuals who do not do their fair share of work on teams, and it can also apply to firms that benefit from a shared resource but do not pay or contribute to its creation or maintenance.

Katz sought to identify reward schemes that achieve the best of both worlds. These hybrid pay systems would reward individual and team performance and promote excellence at both levels. Katz suggested two possible hybrid reward systems. The first system features a base rate of pay for individual performance that increases when the group reaches a target level of performance. In this reward system, individuals have a clear pay-for-performance incentive, and their rate of pay increases when the group as a whole does well. In the second hybrid, the pay-for-performance rate also increases when a target is reached. Under this reward system, however, every team member must reach a target level of performance before the higher pay rate kicks in. In contrast with the first hybrid, this reward system clearly incentivizes the better performers to aid poorer performers. Only when the poorest performer reaches the target does the higher pay rate kick in.

Key Takeaways

- Compensation plans reward employees for contributing to company goals. Pay levels should reflect the value of each type of job to the company’s overall success. For some companies, technical jobs are the most vital, whereas for others frontline customer-service positions determine the success of the company against its competitors.

- Companies should identify the types of teams they have—parallel, work, project, or partnership—and then choose the pay options that are most appropriate.

- Pay-for-performance plans tie an individual’s pay directly to their ability to meet performance targets. These plans can reward individual performance or team performance—or a combination of the two.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What factors would you consider when setting a pay level for a particular job?

- What might be the “A” level positions in a bank?

- If you were running a business, would you implement a pay-for-performance scheme? Why or why not?

- Describe the difference between a base salary, a bonus, and a gainsharing plan.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of rewarding individual versus team performance.

References

Anderson, I., “Human Resources: War or Revolution?,” Mondaq Business Briefing, August 1, 2007.

Chandler, C., “Winning the Talent War in China,” McKinsey Quarterly, November 2009, accessed July 26, 2010, https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Organization/Talent/Winning_the_talent_war_in_China_2472.

Chynoweth, C., “King of the Expat Package,” Times (London), March 14, 2010, accessed July 26, 2010, http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/career_and_jobs/senior_executive/article7060648.ece.

Field, A. and Ken Gordon, “Do Your Stars See a Reason to Stay?,” Harvard Management Update 13, no. 6 (2008): 5–6.

Flannery, T., People, Performance, and Pay (New York: Free Press, 1996), 117.

Garvey, C., “Steer Teams with the Right Pay,” HR Magazine, May 2002, accessed January 30, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3495/is_5_47/ai_86053654/?tag=untagged.

Hoyt, D., “‘Spotlight’ Global Strategic Recognition Program,” Stanford Graduate School of Business Case Study, accessed January 30, 2009, http://globoblog.globoforce.com/our-customers/case-studies/intuit.html?KeepThis=true.

Katz, N. R., “Promoting a Healthy Balance Between Individual Achievement and Team Success: The Impact of Hybrid Reward Systems” (presentation, “Do Rewards Make a Difference?,” session, Academy of Management Conference, San Diego, CA, August 9–12, 1998).

Kerr, S., “On the Folly of Rewarding for A, While Hoping for B,” Academy of Management Executive 9, no. 1 (1995): 25–37.

Lawler III, E. E., The Ultimate Advantage (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992).

Mosley, E., “Intuit Spotlights Strategic Importance of Global Employee Recognition,” Global Trends in Human Resource Management (blog), August 15, 2008, accessed January 30, 2009, http://howtomanagehumanresources.blogspot.com/2008/08/intuit-spotlights-strategic-importance.html.