11.3 Business Entrepreneurship across Borders

Learning Objectives

- Understand why entrepreneurship can vary across borders.

- Recognize how entrepreneurship differs from country to country.

- Access and utilize the Doing Business and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor resources.

How the Ease of Doing Business Affects Entrepreneurship across Countries

There are a number of factors that explain why the level of business entrepreneurship varies so much across countries. In 1776, Adam Smith argued in The Wealth of Nations that the free-enterprise economic system, regardless of whether it’s in the United States, Russia, or anywhere else in the world, encourages entrepreneurship because it permits individuals freedom to create and produce (Smith, 1776). Such a system makes it easier for entrepreneurs to acquire opportunity. Smith was focused mostly on for-profit businesses. However, constraints on the ownership of property might not necessarily constrain other types of entrepreneurship, such as social entrepreneurship.

Business entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship are clearly related. Researchers have observed that in countries where it’s relatively easy to start a business—that is, to engage in business entrepreneurship—then it’s also comparatively easier to be a social entrepreneur as well. One useful information resource in this regard is the World Bank’s annual rankings of “doing business”—that is, the Doing Business report provides a quantitative measure of all the regulations associated with starting a business, such as hiring employees, paying taxes, enforcing contracts, getting construction permits, obtaining credit, registering property and trading across borders (Doing Business website, 2010).

Doing Business is based on the concept that economic activity requires good rules. For businesses to operate effectively, they need to know that contracts are binding, that their property and intellectual property rights are protected, and that there is a fair system for handling disputes. The rules need to be clear yet simple to follow so that things like permits can be obtained efficiently.

The World Bank’s Doing Business Project looks at laws and regulations, but it also examines time and motion indicators. Time and motion indicators measure how long it takes to complete a regulatory goal (e.g., getting a permit to operate a business).

Thanks to ten years of Doing Business data, scholars have found that lower costs of entry encourage entrepreneurship, enhance firm productivity, and reduce corruption (Barseghyan, 2008; Klapper, Lwein, & Delgado, 2009). Simpler start-up regulations also translate into greater employment opportunities (Chang, Kaltani, & Loayza, 2009; Helpman, Melitz, & Rubinstein, 2008).

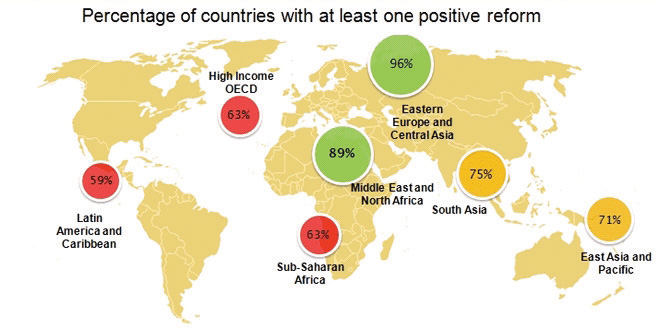

Beyond describing local business practices, one of the key objectives of the Doing Business Project is to make it easier for entrepreneurship to flourish around the world. Considerable progress has been made each year in this regard, with 2010 being noted as a record year in regard to business-regulation reform. The countries with at least one positive reform are shown in the following figure.

Source: “Percentage of Countries with at Least One Positive Reform,” Doing Business, accessed June 3, 2011, http://www.doingbusiness.org/reforms/events/~/media/FPDKM/Doing%20Business/Documents/Reforms/Events/DB10-Presentation-Arab-World.pdf.

Among the most populated countries, the World Bank suggests it’s easiest to do business in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Thailand; the most difficult large countries are Côte d’Ivoire, Angola, Cameroon, Venezuela, and the Republic of the Congo. Among the less populated countries, the easiest-to-do-business rankings go to Iceland, Mauritius, Bahrain, Estonia, and Lithuania; the most difficult are Mauritania, Equatorial Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Guinea-Bissau. You can experiment with sorting the rankings yourself by region, income, and population at http://www.doingbusiness.org/economyrankings.

Differing Attitudes about Entrepreneurship around the World

Entrepreneurship takes place depending on the economic and political climate, as summarized in the World Bank’s Doing Business surveys. However, culture also plays an important role—as well as the apparent interest among a nation’s people in becoming entrepreneurs. This interest is, of course, partly related to the ease of doing business, but the cultural facet is somewhat deeper.

Turkey, for instance, seems a ripe location for entrepreneurship because the country has relatively stable political and economic conditions. Turkey also has a variety of industries that are performing well in the strong domestic market. Third, Turkey has enough consumers who are early adopters, meaning that they will buy technologies ahead of the curve. Again, this attitude would seem to support entrepreneurism. Yet, as Jonathan Ortmans reports in his Policy Forum Blog, currently only 6 percent workers are entrepreneurs—a surprisingly low rate given the country’s favorable conditions and high level of development (Ortmans, 2010). The answer to the mystery can be found in the World Bank’s most recent report, which shows Turkey to be among the most difficult countries in which to do business. The Kauffman Foundation, on the basis of its own assessment, likewise identified many hurdles to entrepreneurship in Turkey, such as limited access to capital and a large, ponderous bureaucracy that has a tangle of regulations that are often inconsistently applied and interpreted. Despite all the regulations, intellectual property rights are poorly enforced and big established businesses strong-arm smaller suppliers (Ortmans, 2010).

However, the Kauffman study also suggests that perhaps the most difficult problem is Turkey’s culture regarding entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs. Although entrepreneurs “by necessity” are generally respected for their work ethic, entrepreneurs “by choice” (i.e., entrepreneurs who could be pursuing other employment) are often discouraged by their families and urged not to become entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurs who succeed are considered “lucky” rather than having earned their position through hard work and skill. In addition, the business and social culture does not have a concept of “win-win,” which results in larger businesses simply muscling in on smaller ones rather than encouraging their growth or rewarding them through acquisition that would provide entrepreneurs with a profitable exit. The Kauffman report concludes that Turkey is in as much need of cultural capital as financial capital.

Did You Know?

The late entrepreneur and philanthropist Ewing Marion Kauffman established the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation in the mid-1960s. Based in Kansas City, Missouri, the Kauffman Foundation is among the thirty largest foundations in the United States, with an asset base of approximately $2 billion.[1] Here’s how Kauffman Foundation CEO Carl Schram describes the vision of the foundation and its activities:

Though all major foundation donors were entrepreneurs, Ewing Kauffman was the first such donor to direct his foundation to support entrepreneurship, recognizing that his path to success could and should be achieved by many more people. Today, the Kauffman Foundation is the largest American foundation to focus on entrepreneurship and has more than fifteen years of in-depth experience in the field. Leaders from around the world look to us for entrepreneurship expertise and guidance to help grow their economies and expand human welfare. Our Entrepreneurship team works to catalyze an entrepreneurial society in which job creation, innovation, and the economy flourish. We work with leading educators, researchers, and other partners to further understanding of the powerful economic impact of entrepreneurship, to train the nation’s next generation of entrepreneurial leaders, to develop and disseminate proven programs that enhance entrepreneurial skills and abilities, and to improve the environment in which entrepreneurs start and grow businesses. In late 2008, the Foundation embarked on a long-term, multimillion-dollar initiative known as Kauffman Laboratories for Enterprise Creation, which, through a set of innovative programs, is seeking to accelerate the number and success of high-growth, scale firms.

In the area of Advancing Innovation, our research suggests that many innovations residing in universities are slow getting to market, and that many will never reach the market. As we look to improve this complex task, we work to research the reasons why the system is not more productive, explore ways to partner with universities, philanthropists, and industry to ensure greater output, and ultimately foster higher levels of innovative entrepreneurship through the commercialization of university-based technologies.

We believe, as did Mr. Kauffman, that investments in education should lead students on a path to self-sufficiency, preparing them to hold good-paying jobs, raise their families, and become productive citizens. Toward that end, the Foundation’s Education team focuses on providing high-quality educational opportunities that prepare urban students for success in college and life beyond; and, advancing student achievement in science, technology, engineering and math.

The Kauffman Foundation has an extensive Research and Policy program that is ultimately aimed at helping us develop effective programs and inform policy that will best advance entrepreneurship and education. To do so, our researchers must determine what we know, commit to finding the answers to what we don’t, and then apply that knowledge to how we operate as a Foundation. Kauffman partners with top-tier scholars and is the nation’s largest private funder of economic research focused on growth. Our research is contributing to a broader and more in-depth understanding of what drives innovation and economic growth in an entrepreneurial world.[2]

(Click the following link to view Schram’s discussion with Charlie Rose about entrepreneurship and education: http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/11026.)

Is there a way for you to gain insights into a country’s entrepreneurial culture and therefore better explain why entrepreneurship varies so much? While there’s no perfect answer to this—just as it’s impossible to provide you with a survey telling you whether you will be a success or a failure as an entrepreneur—you may find it of interest to compare the motivations for engaging in entrepreneurship across countries. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) is a research program begun in 1999 by London Business School and Babson College. GEM does an annual standardized assessment of the national level of entrepreneurial activity in fifty-six countries. The GEM reports are available at http://www.gemconsortium.org.

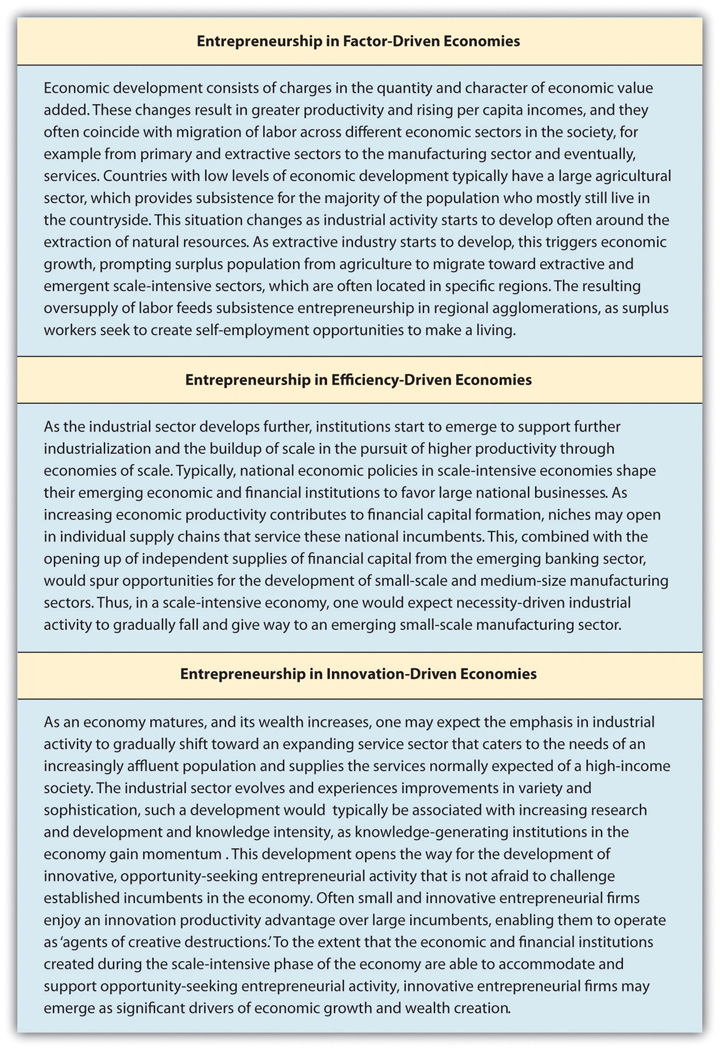

GEM shows that there are systematic differences between countries in regard to national characteristics that influence entrepreneurial activity. GEM also shows that entrepreneurial countries experience higher economic growth. On the basis of another set of surveys and the corresponding index prepared annually by the World Economic Forum (WEF, 2010), countries are broken out in groups, including factor-driven economies (e.g., Angola, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, India, and Iran), efficiency-driven economies (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Hungary, Jamaica, Latvia, Macedonia, Mexico, Peru, Romania, Russia, Serbia, South Africa, Turkey, and Uruguay), and innovation-driven economies (e.g., Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Somewhat like the Doing Business survey, the WEF ranks national competitiveness in the form of a Global Competitiveness Index (GCI). The GCI defines competitiveness as “the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country.” The GCI ranks nations on a weighted index of twelve assessed pillars: (1) institutions, (2) infrastructure, (3) macroeconomic stability, (4) health and primary education, (5) higher education and training, (6) goods-market efficiency, (7) labor-market efficiency, (8) financial-market sophistication, (9) technological readiness, (10) market size, (11) business sophistication, and (12) innovation.[3] Current and past reports are available at http://www.weforum.org/reports.

Factor-driven economies are economies that are dependent on natural resources and unskilled labor. For example, Chad is the lowest-ranked country in the GCI, and its economy is dependent on oil reserves. Because its economy is so tied to a commodity, Chad is very sensitive to world economic cycles, commodity prices, and fluctuations in exchange rates. The pillars associated with factor-driven economies are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, and health and primary education.

Efficiency-driven economies, in contrast, are found in countries that have well-established higher education and training, efficient goods and labor markets, sophisticated financial markets, a large domestic or foreign market, and the capacity to harness existing technologies, which is also known as technological readiness. The economies compete on production and product quality, as Brazil does. Brazil has a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of about $7,000.

Innovation-driven economies, finally, are economies that compete on business sophistication and innovation (Coleman, 2009). The United States, with a per capita GDP of about $46,000, ranks first overall in the GCI due to its mature financial markets, business laws, large domestic size, and flourishing innovation.

Using the criteria for factor-driven, efficiency-driven, and innovation-driven economies and the most recent surveys results, the following figure summarizes the range of activity across a select group of countries.

Key Takeaways

- Entrepreneurship differs in various countries; for instance, it is easier to do business in some countries than others, and this would likely have an impact on the level of entrepreneurship in each country. The Doing Business and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor resources offer insights into everything from a quantitative measure of regulations for starting a business to an assessment of the national level of entrepreneurial activity.

- Citizens of different countries vary in terms of their attitudes toward entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. For example, a country where people viewed entrepreneurs as positive role models and entrepreneurship as a viable career alternative might also encourage others to become entrepreneurs.

- A country’s stage of development also influences its nature of entrepreneurial activity.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Why might the level of entrepreneurship vary across countries?

- Would all the factors that promote or constrain business entrepreneurship also affect the level of social entrepreneurship?

- Do you think some industries would be more affected or less affected by the criteria in the Doing Business rankings?

- Among those factors affecting the level of entrepreneurial activity, which might be the easiest to change and which might be the most difficult? Which might take the most time to change?

- How might a country’s level of economic development affect the nature of entrepreneurial activity?

References

Barseghyan, “Entry Costs and Cross-Country Productivity and Output,” Journal of Economic Growth 12, no. 2 (2008): 145–67.

Chang, R., Linda Kaltani, and Norman V. Loayza, “Openness Can Be Good for Growth: The Role of Policy Complementarities,” Journal of Development Economics 90, no. 1 (September 2009): 33–49.

Coleman, C., “Assessing National Innovation and Competitiveness Benchmarks,” U.S. General Services Administration, March 7, 2009, accessed June 10, 2010, http://innovation.gsa.gov/blogs/OCIO.nsf/dx/Assessing-National-Innovation-and-Competitiveness-Benchmarks.

Doing Business website, accessed July 2, 2010, http://www.doingbusiness.org.

Helpman, E., Marc Melitz, and Yona Rubinstein, “Estimating Trade Flows: Trading Partners and Trading Volumes,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, no. 2 (May 2008): 441–87.

Klapper, L. F., Anat Lewin, and Juan Manuel Quesada Delgado, “The Impact of the Business Environment on the Business Creation Process,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4937, May 1, 2009.

Ortmans, J., “Entrepreneurship in Turkey,” Policy Forum Blog, April 5, 2010, accessed July 2, 2010, http://www.entrepreneurship.org/en/Blogs/Policy-Forum-Blog/2010/April/Entrepreneurship-in-Turkey.aspx.

Smith, A., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776). Recent versions have been edited by scholars and economists.

World Economic Forum website, accessed July 2, 2010, http://www.weforum.org/en/index.htm.

- “Foundation Overview,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, accessed July 2, 2010, http://www.kauffman.org/about-foundation/foundation-overview.aspx. ↵

- “Foundation Overview,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, accessed July 2, 2010, http://www.kauffman.org/about-foundation/foundation-overview.aspx. ↵

- “The Global Competitiveness Report 2008-2009: US, 2008,” World Economic Forum, accessed January 18, 2011, https://members.weforum.org/pdf/gcr08/United%20States.pdf. ↵