Reframing Assessment

10 Self-Assessment in Language Courses: Does In-Class Support Make a Difference?

Gabriela Sweet, Sara Mack and Anna Olivero-Agney

Keywords

self-assessment, language learning, learner agency, Fink’s taxonomy of learning, tools for practice and training in evaluating skills, guided sequence of in-class activities and collaborative learning, student-reported benefit, accuracy in self-assessing, self-regulatory learning

Background

The fact that language learners benefit from a critical examination of their own strengths and weaknesses is well established. Oskarsson (1984) conducted a literature review of this “relatively new field” (p. 1) over 30 years ago. By that time it was already documented that learners who are trained and supported in self-assessment become reliable evaluators, with judgments correlating closely to external measures such as standardized tests and instructor estimates. Additionally, Oscarson (1989) suggested a list of key rationale for using self-assessment procedures in language learning. In the intervening years, most of these once “speculative” (p. 3) rationale have been confirmed empirically, showing that self-assessment increases the level of awareness and improves goal orientation (Moeller, Theiler & Wu 2012). The most recent studies continue the trend of documenting self-assessment as a powerful tool to enhance language learning (Ziegler 2014; Dolosic et al 2016).

While the efficacy of self-assessment is now widely accepted in general terms, few studies have examined large-scale efforts to provide training and support in self-assessment for learners at the postsecondary level. With approximately 1.5 million students in college-level language courses other than English annually (MLA 2015), there is a clear need to more closely examine self-assessment in this context, not only documenting its benefits, but critically analyzing how self-assessment is conducted and what procedures are most beneficial to this population of learners. To address this question, this paper reports on an experiment using two versions of a large-scale self-assessment protocol developed at the University of Minnesota, Basic Outcomes Student Self-Assessment (BOSSA).

BOSSA is a proficiency-based standardized protocol for language learning that makes self-assessment meaningful to students through concrete grounding in performance. It consists of tools for speaking and writing, appropriate for language learners at different proficiency levels. The core BOSSA experience is generally delivered in a computer lab and lasts approximately 50 minutes. Its innovative design consists of an articulated, guided sequence of activities plus a self-assessment questionnaire. Students benefit from trying out language tasks related to course outcomes and practice evaluating their skills as they identify their language strengths and areas that need work, and set specific goals (personal or course-related) to address the gaps they perceive.

Further, the evidence-generating protocol provides actionable feedback to students, instructors, and programs. Learners are provided with an individual data report, and can monitor their progress over time as they work towards achieving goals. Instructors and programs can use aggregate data from a class-level learner profile to reflect on course and program proficiency goals. Measurable outcomes include increased awareness, learner agency, and engagement in learning.

The evidence-generating protocol provides actionable feedback to students, instructors, and programs. Learners are provided with an individual data report, and can monitor their progress over time as they work towards achieving goals. Instructors and programs can use aggregate data from a class-level learner profile to reflect on course and program proficiency goals. Measurable outcomes include increased awareness, learner agency, and engagement in learning.

This article focuses on the BOSSA protocol for examining speaking skills. There is also a full BOSSA protocol for writing that similarly pairs language performance tasks, opportunities for reflection, and a self-assessment questionnaire. In addition, there are self-assessment questionnaires for listening and reading, with plans to develop the full protocol for these skills.

The speaking protocol includes the elements of BOSSA noted above, including communicative language performance tasks, reflection first alone and then with peers, practice in developing the skill of self-assessment, and culminates with students completing the self-assessment questionnaire, rating their language skills. As with the BOSSA writing protocol, the questionnaire results are electronically tabulated and learners receive a customized report of how their (self-assessed) skills compare with course goals, along with suggestions on how to improve.

The BOSSA experience has resulted in a paradigm shift, promoting shared responsibility for learning between students and instructors. This aligns with Fink’s (2013) call for a shift from a content-centered paradigm to one that puts the learner at the center. He suggests that course design be grounded in the premise that learning effect real and lasting change in one’s life. In the content-centered approach, instructors “respond to the question of what students should learn by describing the topics or content that will be included in the course” (p. 60). In contrast, Fink’s learner-centered focus creates a more favorable environment for learners to retain what they learn in the class and increasing the likelihood that they will have the tools and motivation needed to keep learning after the course ends (p. 63).

The shift initiated by BOSSA corresponds to several categories of Fink’s learner-centered paradigm. These categories (Integration, The Human Dimension, and Learning How to Learn) emphasize higher-order metacognitive skills. BOSSA’s guided discussions and self-assessment questionnaires align with Fink’s concept of Integration, providing an opportunity for students to transfer what they are learning in class to other contexts. Learning becomes more meaningful when students can align course objectives with personal goals.

Those same BOSSA elements also highlight the Human Dimension, raising student awareness that learning another language can, in Fink’s words, “…affect their own lives and their interactions with others” (p. 90). In providing a frame for students to reflect on their learning and fill the gaps– and provide each other with support and feedback in that process– BOSSA promotes the value of collaborative learning and problem-solving.

The most significant connection between BOSSA and the learner-centered paradigm is in the Learning How to Learn category. Fink (2013) outlines three distinct forms in this category: “becoming a better student, learning how to inquire about […] particular subject matter, and becoming a self-directed learner” (p. 91). BOSSA supports all three of these aspects, focusing on the process of learning, via its integrated set of activities. In other words, through BOSSA, students are at the center, learning to articulate not only what but how they learn language, thus taking charge of the trajectory. In the words of one student, “It was a huge wake-up call for where I was in my language learning. This has definitely helped with my proficiency and confidence.” And from an instructor, “I see that my students are much more self-aware of their own skills, struggles, and goals in relation to the target language. I think this self-awareness is empowering.”

The BOSSA protocol was originally developed for students in Intermediate Spanish courses, then extended to serve students in French, German and Italian, and today also supports students of Arabic, Chinese, English, Hmong, Korean, Portuguese, and Russian. After its first year of development and use, Language Flagship funding for the Proficiency Assessment for Curricular Enhancement (PACE) project supported further development of BOSSA. BOSSA currently serves an average of 3,000 students each academic year. This large-scale use within and across languages has operationalized self-assessment in second language classes at the University of Minnesota, and standardized the process so the benefits of self-assessment are available to students regardless of the language they study.

Original Version of the BOSSA Protocol

The original version of the BOSSA procedure requires learners to complete the majority of the protocol tasks in a computer lab. Many courses integrate two 50-minute class periods into the course calendar for the protocol, one at the beginning of the semester and one at the end, when students can see the progress that they have made.

The lab session has six components. First, students watch a two-minute video that introduces them to self-assessment and familiarizes them with criteria they will use later to evaluate their skills. The video standardizes delivery of the message across languages and levels. Instructors facilitate the session, rather than being at the center as “teacher”. Students warm up with a short conversation activity, activating their second language prior knowledge. The instructor provides the topic, usually based on what students have been working on in class at that point of the semester.

The second component is the Speaking Practice Task (SPT). Students complete the SPT via computer, using headphones and microphones. The in-house created content supporting this component is delivered through an easily navigable web interface that guides learners through the language performance task. Each SPT is contextualized, giving students a reason to use the language, and consists of three steps. Each step has a slightly different communicative context. Students have the opportunity to show what they can do by responding to prompts, within the frame of a general topic and task. For example, beginning students introduce themselves and talk about their likes and dislikes, while students at the advanced level make explanations and provide solutions for situations that include an unexpected complication. Backward design aligns tasks (topics and functions) with what students are expected to be able to do by the end of the instructional level. So the SPTs are tied to specific, tangible outcomes or objectives on the course, program, and national standards levels. Responses are recorded. There are four SPTs, each calibrated to a different proficiency level; they last between nine and fourteen minutes (depending on level).

Listening and using criteria to reflect is where practice and training with self-assessment begins. After completing this third component, the SPT, students listen to their own recordings and use criteria to reflect on how well they spoke in completing the language tasks. The criteria address the following areas: vocabulary and fluency, complexity, accuracy and comprehensibility, and communication strategies. They are aligned with course objectives and criteria used for summative assessments. A short description explains to students what each criterion entails. The recordings provide students with something concrete for them to refer to, making it easier to reflect on their abilities. The criteria introduce students to thinking about, evaluating, how they use language; for example, whether they actually do use complete sentences when they speak. Again, this is what makes BOSSA unique: it integrates a real time performance opportunity with self-assessment. Students report that being able to hear themselves speak is very valuable; for some, it’s the first time they’ve done this. For most, this quick check-up serves as a wake-up call that comes from themselves, not from their instructor. And thus, self-awareness begins.

This is what makes BOSSA unique: it integrates a proximal performance opportunity with self-assessment. Students report that being able to hear themselves speak is very valuable; for some, it’s the first time they’ve done this. It’s like giving themselves a quick check-up; a wake-up call that comes from themselves, not from their instructor. And thus, self-awareness begins.

At this point in the experience, students have started to think about what they can do, grounding their awareness via reflection on their performance on a set of concrete tasks. Now they are ready to work in pairs in the fourth component, deepening that metacognitive self-awareness by processing ideas with a classmate. This is where the paradigm starts to shift: as students reflect, they begin to think about their studies as a place where they can be in charge and where they can take control. The collaborative pair work is an additional opportunity for students to think about how language learning works, and share notes about their strengths and challenges and set specific, realistic goals for improvement. They begin to see that it’s up to them to do the work, taking charge to make changes, translating reflection into action. This is all done in English, the native language of the majority of our students, so that students can reflect more deeply.

The fifth component is class discussion. Students lead the discussion about strengths and challenges within the larger framework of proficiency in their own words. As they talk, instructors record the discussion on the whiteboard and reformulate what students say in terms of the criteria, thus providing language that allows them to articulate and reflect on how they learn with concrete examples. The board is photographed so that students have a record later. The instructor also facilitates the class discussion, as needed, to help students understand what is realistic in terms of proficiency goals per course expectations. Students report that this is a very valuable component of the protocol: “In your head you think that everyone is better than you, and then in class discussion… you don’t feel as bad, now I am not alone and I can work on that.” By finding common ground and exchanging suggestions, students take ownership and gain autonomy. Doing something individually, then in pairs, and then, in the large group, builds confidence.

In the sixth, and final component, students use an online, self-assessment questionnaire to rate their speaking ability. This step brings together all of the knowledge gained in the lab session: students have a specific idea of their skills in light of their actual speaking performance in the SPT, and they have new knowledge (from the discussion) that helps them assess those skills in terms of general language learning goals, goals specific to the course, and their own individual goals.

After the students complete the online self-assessment questionnaire, a summary of their results appears on-screen. Results consist of two main parts: a score and a proficiency level based on their self-reported performance rating, and a description of what language learners like themselves can do at their self-rated level of proficiency (additional support toward realistic expectations). Students also get results via email, which includes their responses to individual items, specific learning strategies for their individual learning preferences and goals, and information on other proficiency levels (not just the one at which self-assessed).

The Modified BOSSA Protocol

In Spring 2016, a pilot funded by an Experiments in Learning Innovation (ELI) grant explored whether learners can use the self-assessment protocol, forging their own path to self-awareness and self-regulated learning – on their own turf and on their own terms – as effectively as in the classroom. This effort to adapt the BOSSA protocol for use outside of the computer lab was in response to feedback on the original BOSSA protocol gathered in focus groups with students and instructors. The focus group data indicated that instructors were concerned that making time for the computerized self-assessment protocol in the lab would decrease time available for other course content. In addition, they wanted students actively using and reflecting on language use outside the classroom. Students wanted to have their own recordings, something difficult to arrange given the current delivery model in the lab. Furthermore, lab time in the computer labs can be difficult to book as nearly all language programs at the University of Minnesota frequently make use of the technology labs have to offer throughout the semester.

The modified at-home delivery could not guarantee the built-in speaking practice and training in self-assessment before students evaluate their skills, precisely the element which sets BOSSA apart from other self-assessment protocols.

In this modified BOSSA approach, the second round (near the end of the semester) takes place both at home and in the classroom, rather than completing all steps in the language lab. Students complete the SPTs at home, listening to their recordings and evaluating their skills using a worksheet. They also reflect on how they have improved since the first time they completed the SPT and what they did to improve. The following day, in class, students continue the reflective activity in pairs, sharing their notes. Class discussion follows and at the end of the class session students use computers, phones, or other electronic devices to access and complete the online self-assessment questionnaire, as in the original format of the protocol. Instructors were free to use a variety of approaches to realize the reflection. For example, some instructors assigned students to do the entire process (including completing the online self-assessment questionnaire) at home, and followed up with a brief discussion during the next class session. Others made the SPT optional, requiring only that students complete the online self-assessment questionnaire as a homework assignment. Instructors later reported partial completion of the assigned tasks, as it turned out that many students had opted not to do the SPT at home, or had not listened to their recordings and evaluated their skills. Therefore, they were not prepared to reflect on the proximal performance experience of the SPT, making it difficult to realize the benefit of collaborative learning during class discussion. In effect, the modified at-home delivery could not guarantee the built-in speaking practice and training in self-assessment before students evaluate their skills, precisely the element which sets BOSSA apart from other self-assessment protocols.

Procedures, Results, and Analysis

Quantitative data analyses compared the efficacy of the modified BOSSA delivery with that of the original format. Approximately 340 students of a variety of languages and levels participated, with half completing the original, completely in the lab format (henceforth referred to as “R2”, for “Round 2 in lab”) and half completing the modified, mixed at-home and in-class format (“R2M”, for “Round 2 modified”). Data were gathered via a survey measuring how self-assessment impacts student self-awareness, self-regulatory learning, and performance. Survey responses were also analyzed to determine to what extent the awareness students gain through doing BOSSA practice activities is associated with increased accuracy in self-assessment. To measure this, students’ self-assessment was compared with their skills as measured by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) test battery.

Preliminary analyses show that in both versions of the BOSSA protocol, self-assessment in language learning leads to a higher level of learner agency and awareness of the language learning process (greater than 70% in each). However, the effect is especially strong when learners are provided with training in rating their skills through the original format in which all six components are done in the lab during class time.

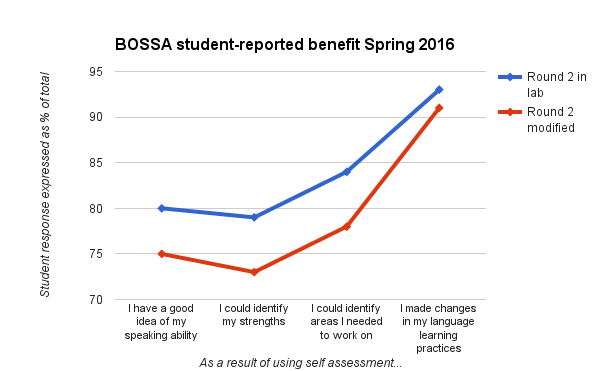

On a survey collecting student-reported benefit to using the protocol after the end-of-semester BOSSA session, students using the two formats responded very differently to an item focused on the practice and training aspects of BOSSA (see Figure 1, next page). Three-quarters of those using the R2 format said that the opportunities to practice (including the SPT, pair work, and class discussion) helped them feel prepared to complete the online self-assessment questionnaire, while only two-thirds of those using the R2M format reported that practice helped. Students qualified the overall experience similarly, with 74% of those using the R2 format reporting that self-assessment helped their language learning, as compared to 67% of those using the R2M format. Further, 82% who did the BOSSA protocol in the lab said that they could identify both strengths and things they needed to work on, while 76% of the mixed at-home and in-class users reported self-awareness around these areas. In addition, both groups reported that they had made changes in their language learning practices in response to using self-assessment, with slightly higher reported benefit from those using the R2 format.

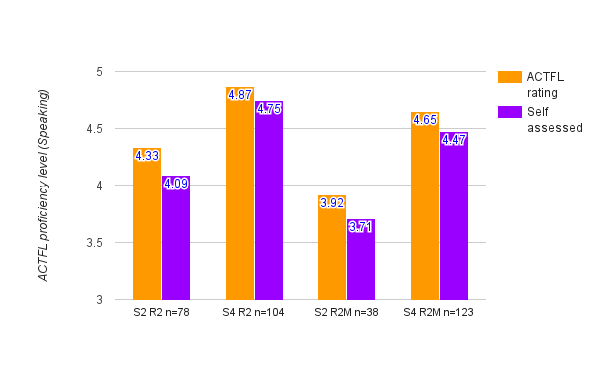

In terms of accuracy, learners provided with training and regular opportunities to rate their skills in the lab setting self-assess more accurately than those who engage in the process in a mixed at-home and lab setting. ACTFL proficiency ratings using the Oral Proficiency Interview – Computer (OPIc) test were examined together with students’ self-assessed proficiency ratings to determine to what extent students’ self-evaluations of their skills matched up with their performance. Data were analyzed first by aggregating per semester of instruction, and then comparing both overall mean (second-semester and fourth-semester levels) and by-person ratings from the two groups. The R2 group for whom there were both ACTFL data and self-assessment data consisted of 182 learners of Arabic, German, and Portuguese (78 second-semester and 104 fourth-semester students); the R2M group was made up of 161 learners of French, Korean, and Russian (38 second-semester and 123 fourth-semester students) for whom there were both ACTFL data and self-assessment data.

Figure 1: Student-reported benefit: Using self-assessment to support language learning

Students in both the R2 and R2M groups tend to assess their speaking skills lower than how they are rated by ACTFL (as illustrated in Figure 2) with fourth-semester learners (S4) in general self-assessing a bit more accurately than second-semester learners (S2). Representing ACTFL proficiency levels using integers (e.g., 3=Novice High, 4=Intermediate Low, 5=Intermediate Mid), and based on semester of instruction mean ratings, learners who had the full support of an integrated BOSSA session (R2) in the lab evaluated their speaking skills within .36 of how they were rated, while those using the mixed format (R2M) evaluated their skills with less accuracy, or within .39 of their ACTFL rating (aggregating second- and fourth-semester data).

Looking more closely at how individual students self-assess their speaking skills as compared to how they are rated by ACTFL, the data show a high degree of accuracy at or within one sub-level on the proficiency scale (for example, self-assessing at the Intermediate Low level and being ACTFL rated Intermediate Low or Intermediate Mid) for all learners, using both formats (see table below). Those completing all activities in the lab self-assess slightly more accurately than those who did some activities at home and some in class. The margin for second-semester learners (N=78) was very slight, with only a tenth of a percentage point of difference: R2 users (students of Arabic) self-assess with 94.9% accuracy at or within one sub-level as compared to R2M users, (students of Russian) at 94.8% accuracy. There is more divergence in the data for fourth-semester learners (N=227): R2 users (students of German and Portuguese) self-assess with 99% accuracy at or within one sub-level as compared to R2M users, (students of French, Korean, and Russian) at 96.6% accuracy (see Table 1).

Figure 2: Comparison of ACTFL OPIc and self-assessed mean ratings: Semester-level accuracy (R2 & R2M)

Table 1: Person-level accuracy in self-assessment (R2 & R2M)

| Too Low (2 or + sub-levels) | Too Low (1 sub-level) | ACCURATE | Too High (1 sub-level) | Too High (2 or + sub-levels) | |

| Semester 2 R2 n = 78 | 1.3 | 33.3 | 44.9 | 16.7 | 3.8 |

| Semester 4 R2 n = 104 | 0 | 21.1 | 44.2 | 33.7 | 1 |

| Semester 2 R2M n = 38 | 2.6 | 31.6 | 42.1 | 21.1 | 2.6 |

| Semester 4 R2M n = 123 | 1 | 21.9 | 59.3 | 15.4 | 2.4 |

Discussion and Conclusions

3.1 Limitations of the study

Data from the student feedback survey and performance data, comparing ACTFL proficiency ratings to how students self-assess, show that the fully supported session in the lab yields higher student-reported benefit, learner agency, and accuracy. However, the high degree of variation present in the mixed at-home and in-class R2M format limit the generalizability of these data. There were differences in terms of administrative oversight, specific methods of delivery, student compliance, and, to some degree, deviation from original purpose in terms of BOSSA goals (all elements that were not possible to control in this study situation). At the same time, this kind of variation is to be expected in real-life circumstances; administrators of any large-scale delivery will encounter similar variation.

3.2 Future directions

Through the Experiments in Learning Innovation grant, the researchers were able to look more closely at how BOSSA works for students and programs. It is clear that while the BOSSA protocol is adaptable for use outside of the language lab setting, more investigation is indicated in order to increase the efficacy of the modified delivery mode. BOSSA was created with the understanding that it would be an ongoing iterative dialogue between end-users and developers. As the protocol’s reach continues to expand as a support for language learning at the University of Minnesota, it has potential to serve as a model that is easily adaptable for use by other programs of study.

At the same time, we – the instructors and researchers who created BOSSA – need to continue to grow through exploration and research, refining theory and design through our findings, and implementing improvements. BOSSA is a workable solution for a wide range of language programs that are charged with supporting students of all levels, using a standardized approach that is highly structured but still able to be customized to address specific needs. We recognize that this balance between standardization and customization is vital. For example, we have learned that some students don’t feel qualified to rate themselves; they don’t see yet that self-assessment is a skill like any other, which improves with practice. It would serve those students well to focus more on building confidence through regular use of the self-assessment process. And instructors, while acknowledging the clear benefit of the protocol to students, say they would like support in terms of how and when to use additional self-assessment opportunities throughout the semester. BOSSA helps students to become agents of their learning through the cycle of using the tool for themselves and reflecting analytically. In the future, increased practice, training, and regular use of self-assessment, especially those integrated as class activities, seem key to continuing to foster learner agency.

Conclusion

We’ve seen clear benefits of using self-assessment to support second language learning at the University of Minnesota. However, a close analysis of how students experience self-assessment –whether in a supported, guided, lab class session atmosphere using standardized delivery, or through completing some activities on their own and others with peers in the classroom setting – shows that a climate that supports reflective learning in the lab class session setting results in higher learner agency and awareness, as well as accuracy in learners evaluating what they are able to do. We’ve learned that self-assessment must strike a balance between students realizing that they can take control of their learning, while still benefiting from external guidance. This guidance can be from instructors directly or through the messaging that BOSSA’s lab delivery provides, especially in the careful scaffolding of activities where reflection leads to self-awareness, and training prepares students to complete the self-assessment questionnaire at the end of the session.

In contrast, data show that a lack of standardized delivery in terms of how self-assessment is introduced and conducted results in students experiencing less benefit insofar as how they see their own ability to be in charge of their learning and in their ability to accurately evaluate their skills.

An examination of what procedures are most beneficial to our learner population indicates that students benefit from the guided critical examination of their own strengths and weaknesses in the lab setting. Here is feedback from a student after her first time participating in a BOSSA lab session:

With that type of power [from a BOSSA session] and the change in your consciousness, it’ll make you pursue your learning in a different way, in a more intentional way, because not only do you have the tools to track what you’re doing, but you want to do better. And you are also able to identify your personal goals. At the same time it makes your learning more practical, because you think, “How is going to apply in my life, outside of the classroom?” Not just “How well am I going to do on the next test?” It’s just really extremely effective as a learning technique […] because it makes us intentional learners.

In conclusion, the guided training and support that students receive in self-assessment in a lab setting, integrating a proximal performance experience as basis for reflection on ability and coupled with collaborative metacognitive discussions of learning, work in tandem to promote increased learner agency, empowerment, and awareness about what learners themselves can do. While there are multiple ways to deliver and manage this process, this study suggests that the most beneficial method is one in which learners learning about self-assessment, and have opportunities to build their self-assessment skills via interaction with their peers in the lab class session setting.

References

Dolosic, H. N., Brantmeier, C., Strube, M., & Hogrebe, M. C. (2016). Living Language: Self‐Assessment, Oral Production, and Domestic Immersion. Foreign Language Annals, 49, 302–316.

Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Fall 2013. David Goldberg, Dennis Looney, and Natalia Lusin.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. John Wiley & Sons.

Moeller, A. J., Theiler, J. M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal Setting and Student Achievement: A Longitudinal Study. The Modern Language Journal, 96(2), 153-169.

Oskarsson, M. (1984). Self-Assessment of Foreign Language Skills: A Survey of Research and Development Work. Council for Cultural Cooperation.

Oscarson, M. (1989). Self-assessment of Language Proficiency: Rationale and Applications. Language Testing, 6(1), 1-13.

Ziegler, N. A. (2014). Fostering Self‐Regulated Learning Through the European Language Portfolio: An Embedded Mixed Methods Study. The Modern Language Journal, 98(4), 921-936.

This research was supported in part by grants from the Center for Educational Innovation, University of Minnesota, and the Language Flagship Program Initiative of the National Security Education Program, U.S. Department of Defense.