Building New Course Structures

9 Translating Knowledge to Engage Global Grand Challenges: A Case Study

Daniel Philippon, Barrett Colombo, Fred Rose and Julian Marshall

Keywords

interdisciplinary, trans-disciplinary, active learning. competencies, grand challenges, co-curriculum

Introduction

In fall 2014, the University of Minnesota adopted a new strategic plan to transform both research and teaching to address society’s grand challenges. This plan outlined a series of adaptive changes to infuse grand challenges across the curriculum. Recommendations included a new vision for liberal education requirements, including the development of introductory to advanced course categories that, through the arc of a student’s career, would allow varied and sophisticated engagement in a challenge. To accomplish these goals, the University created a Grand Challenge Curriculum (GCC) designator, placed at the Provost level, and started a phased implementation of new cross-collegiate curricular and co-curricular arrangements for revenue and cost-sharing.

In fall 2015, the University focused its efforts on testing and developing promising models that could bring the plan’s ambitious goals to scale across one of the largest land-grant research universities in the U.S. In particular, an initial priority was to develop new introductory seminars focused on a variety of grand challenges. Each of these introductory seminars was meant to integrate multiple disciplines into course design and pedagogy and promote “active learning” approaches in the classroom.

At the same time, no matter the particular grand challenge, the University emphasized that each introductory GCC seminar should focus on “competencies that prepare students to recognize grand challenges, assess possible points of intervention, and take action” (Cheng, Schively Slotterback, et al). As a result, while the content of each course varied greatly, each course was to have a common interest in building students’ ability to take practical, real-world action in response to the challenge and to communicate their ideas effectively.

This article outlines the efforts of a group of faculty and instructional staff teaching across a number of GCC courses to develop appropriate curricular and co-curricular structures to support these foundational competencies.

This instructional team eventually coordinated the instruction of four courses during Fall 2015:

- GCC 3001 – Can We Feed the World Without Destroying It?

Profs. Jason Hill (College of Food, Agricultural, and Natural Resource Sciences) & G. David Tilman (College of Biological Sciences) - GCC 5003 – Seeking Solutions to Global Health Issues

Prof. Cheryl Robertson (College of Nursing) - GCC 5005 – Global Venture Design—What Impact Will You Make?

Prof. Julian Marshall (College of Science & Engineering) and Fred Rose (University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment) - LA 3003/5003 – Climate Adaptation for Minneapolis

Vincent deBritto (College of Design)

Three of the courses were part of the University’s GCC. The GCC has a number of requirements for course design that promote an interdisciplinary approach to problem-solving, including a requirement of co-instruction from faculty across at least two colleges and the expectation that faculty actively collaborate (and not simply switch off) on instruction during class. Further, as introductions to a particular challenge, all three GCC courses had no content prerequisites—advanced undergraduates or graduate students were welcome to apply, no matter their major program of study. The fourth course, though taught from the Dept. of Landscape Architecture, shared many of the same educational objectives of the other courses.

Project Background

Distinct content needs

As a specialized introduction to a global grand challenge, each course necessarily devoted 30-70 percent of course hours to developing students’ literacy in the challenge itself. While some content did overlap from course to course, the specific challenge addressed by each course generally required that students be immersed in distinct disciplinary and professional knowledge. For example, in “Can we feed the world without destroying it?,” students were introduced to literature from ecology, population studies, the history of science, agricultural policy, genetic engineering, agroecology, biosystems engineering, and political economy. In contrast, “Seeking Solutions to Global Health Issues” introduced students to cutting-edge understandings of emerging pandemic threats, disease ecology, refugee policy, women’s and gender studies, the history of immigration, health systems policy and institutions, public health policy, international political economy, and veterinary population health.

Despite these differences, instructors felt that some overlap in content was necessary for students to engage in each of their grand challenges. Most notably, nearly all courses required that students study one particular overarching grand challenge—the impacts and feedbacks affecting their issue due to global climate change.

Common emphasis on real-world, practical impact

Despite widely different kinds of content, all of the courses emphasized the need to move from a survey of the challenge—in effect, an understanding of the problem—to taking some kind of action to respond to the challenge.

The co-curricular pilot project originated from the shared belief that, despite the differences between particular grand challenges, students would require a common set of trans-disciplinary skills to develop solutions to these challenges. In other words, the assumption was that common approaches might exist in helping students translate their knowledge about grand challenges into creating some tangible impact on those challenges

Instructors also assumed that practical impact could take many forms, depending on the challenge and also on the students’ theory of change. Social change can occur from a broad range of actions. However, whether developing a public art installation, a public health implementation plan, a social venture business plan, or a narrative essay, the team assumed that there might be some common approaches in moving from problem to action.

Curricular Structure

While taught by separate instructional teams, and designed according to the goals of those instructors, all courses were to feature the following common four core elements:

- Creating a Knowledge to Impact Skills Lab: A new “skills lab” featuring modules focused on different trans-disciplinary skills, to be integrated within each course, or taught separately as a 1-credit option.

- Proposing solutions that respond to some aspect of the wider challenge:Within each course, interdisciplinary teams of students would work in a studio environment, coached by instructors and mentors, to create solutions that could potentially be implemented.

- Holding a common workshop event across multiple GCC courses:All courses would emphasize early feedback for student teams through studios and presentations. In addition, all students would present at a final workshop event, including students from other challenge courses, and proposals would be reviewed by experts drawn from UMN faculty and the MSP professional community.

- Supporting students in developing solutions beyond the class: Students would be guided toward funding to implement their ideas, enroll in other courses at the University, etc.

These goals and this curricular structure remained largely intact, with some modifications:

Creating a Knowledge to Impact Skills Lab

We developed and piloted the “Knowledge To Impact” (KTI) curriculum to prepare students with skills and frameworks that would enable them to use the knowledge gained in their GCC course to create plausible solutions. Solutions could take varied forms according to the needs of the challenge, including sustainable business or non-profit models, public policy, public health interventions, media, or technical solutions. To more easily meet the needs of varied GCC course structure and timelines, KTI was developed in a modular fashion, with each module focused on a different trans-disciplinary skill. The only prerequisite for KTI was that students were currently enrolled in another GCC course.

The lab introduced students to skills for engaging with other people effectively to address a challenge. These included both oral and written communication training, developing effective presentations, elements of storytelling, and integrative leadership. The lab also provided introductions to skills that allow students to better approach complex problems. These included systems dynamics, quantitative reasoning, and design thinking and its array of skills (i.e., problem scoping, stakeholder mapping, prototype and iteration).

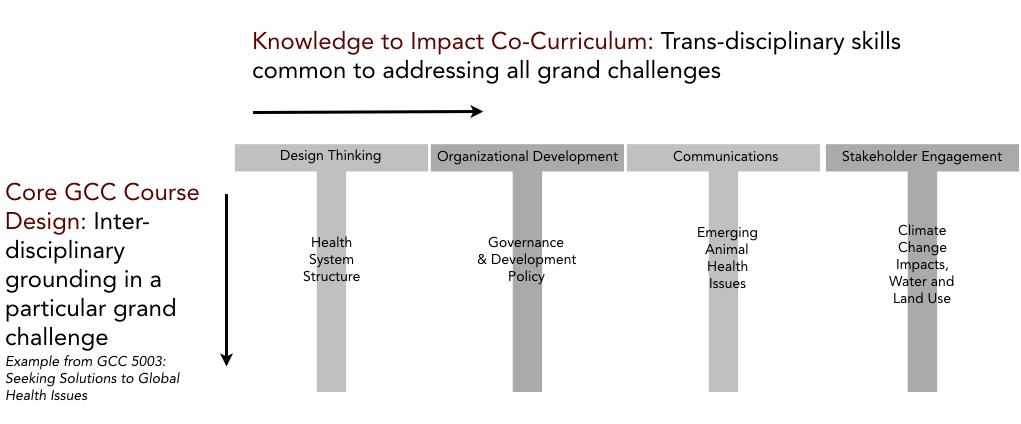

Figure 1: Curricular Structure Overview for Core GCC Course Design1

Proposing solutions that respond to some aspect of the wider challenge

Our project team shared the following learning outcomes. Students will:

- understand the path from idea to impact and apply this knowledge through a project in their GCC course

- apply design thinking to identify a suitable problem relevant to their Grand Challenge

- identify a problem they wish to focus on, and create an actionable problem statement relevant to their Grand Challenge

- propose a solution that addresses the problem in some way

- share their proposal with practitioners in their challenge area who could advise on how to improve it

Across all four courses, students worked in teams of 3-5 to develop projects designed around these outcomes. Examples of proposals include:

- A food delivery social venture plan to deliver produce to university students

- A pilot social network focused on farmers in the Upper Midwest around the issue of aquifer sustainability

- A food waste reduction curriculum pilot for Minneapolis Public Schools

- A public health intervention plan to improve patient satisfaction in Uganda

- A microfinance business plan designed to reduce incidence of diarrhea in Uganda

Holding a common workshop event across multiple GCC courses

Our end-of-semester KTI workshop event featured approximately 125 students from across three GCC courses, plus the participating LA 3003 course. The goals of the workshop included:

- Students’ awareness of their participation in the University’s broad effort to address society’s grand challenges through teaching and research

- An emphasis on providing feedback for refining each team’s projects

- A video, produced by the University of Minnesota, featured GCC students preparing for and participating in the event.

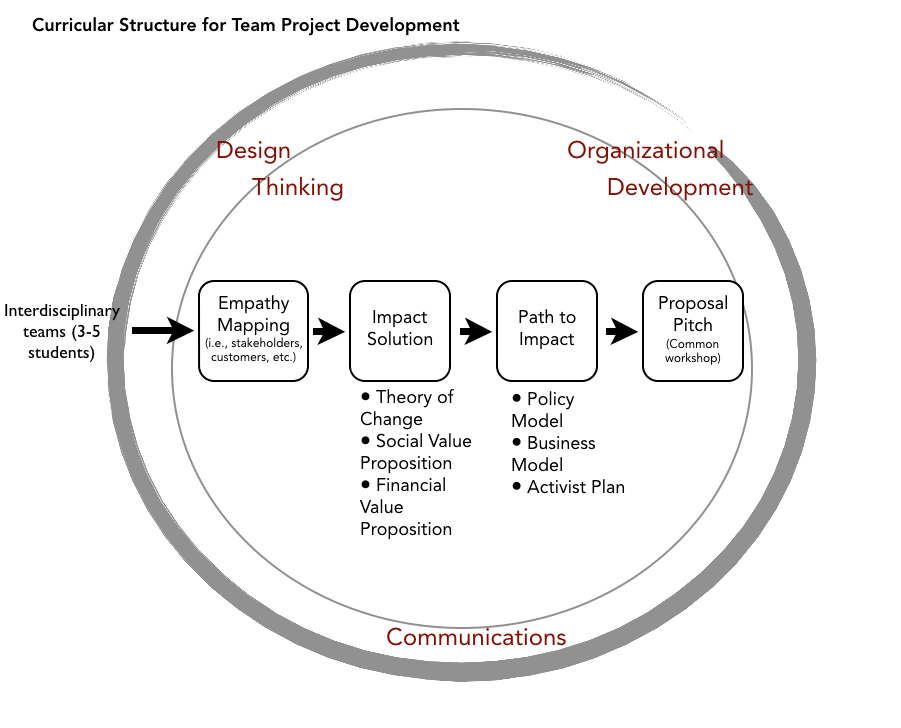

Figure 2: Curricular Structure for Team Project Development2

Supporting students in developing solutions beyond the class

The UMN Strategic Report on Grand Challenge Curriculum notes that students ultimately require an arc of opportunities for developing their capacity and knowledge. To move toward this integration, our suite of courses adopted the following strategies:

- A Grand Challenge Studio Session: Scheduled office hours with instructors/mentors to review developing proposals. Mentors were drawn from the MSP professional community and available to interested students beyond their particular course.

- Deliberate efforts to make students aware of other course and non-course opportunities (i.e. funding competitions, co-curricular opportunities, etc.) at the University.

Evaluation

We conducted a post-class evaluation in the three GCC classes, in part by asking students to describe their experiences on post-it notes. Six themes emerged:

- “Challenging.” The most common word students used to describe the Grand Challenge Courses was “challenging.” Twenty students across the three classes wrote “challenging” and others added a host of similar words such as “stressful,” “overwhelming,” “intense,” and even “nerve wracking.” Although the term “Grand Challenge” may have originally been meant to describe large, complex global problems, it simultaneously came to represent the steep learning curve that many students faced in these courses.

- “Eye-opening.”The Grand Challenge Courses opened some students’ eyes to new perspectives on themselves, the world, and how change really happens. A number of students found the classes to be innovative (8), eye-opening (7), thought-provoking (5), provocative (3), and similar words, including “mind-blowing” and “game-changing.” When these students placed their post-it notes describing their GGC, we asked if similar words would describe most of their other UM experiences. In each case, they quickly responded (sometimes with laughter) that they would not. Verbally, many shared that it changed how they saw themselves and what it takes to change the world.

- “Inspiring.” The Grand Challenge Courses motivated some students to be global change makers. Some students’ words reflected that they were personally inspired by the GCC. They found the experience “inspiring” (9) and used other related words such as “beyond important,” “meaningful,” “character-building,” and “empowering.” As one student shared: “I came to the class having an idea of how complicated the problems are, and was curious how the class would break down those problems. What changed for me personally was the idea that complicated problems can be addressed if we work on them relentlessly.”

- “Enjoyable.” Some students expressed that they enjoyed the experience. Multiple students found the Grand Challenge Course format enjoyable. Despite the experience being sometimes “stressful,” students expressed that it was “fun” (6) and used similar words such as “engaging,” “refreshing,” “amazing,” and “rewarding.”

- Unconventional Class Structure. Twenty students, especially in the “Feed the World” class, chose to comment that they found the class format to be “unconventional.” Students also selected words indicating that the structure of a GCC was different from the norm. They called the GCCs “unorthodox,” “unconventional,” and even “crazy.” There were also a number of words commenting on the “collaborative” (5) and “hands-on” class structure.

- Metacognitive Class Content. Some students focused their word choices on the type of thinking that the Grand Challenge Courses required. Student words also focused on the metacognitive skills needed to be global change-makers. In the “Feeding the World” class, seven students wrote the class was “scientific.” Other words reflected the need for “empathy,” “creativity,” “ideation,” and “deep thinking.”

Limitations of Evaluation

It should be noted that this report represents a snapshot of student reflections and is not meant to substitute for a formal class evaluation. Also, the students presented their feedback with the instructors present, which may have constrained critical commentary. What students did share, however, reveals important thoughts about the Grand Challenge Course potential that should be combined with the standard Student Rating of Teaching (SRT) survey to gain a fuller view of the GCC progress and challenges. As one student commented: “We really are the guinea pigs of the university Grand Challenge Courses. It’s neat to be part of the beginning!”

Future Directions

Curricular ideas

- Adapt the curriculum to other kinds of challenges, especially non-environmental grand challenges.

- Encourage teams to develop other types of “products” where a social venture plan, policy intervention, etc. may not be not appropriate. Other “products” that are equally likely to create change include narrative pieces (i.e., videos, articles, photo-essays, etc.) and epistemologies for approaching these challenges. This would mirror the approach of a pilot GCC course, HCOL 3805H – Our Common Waters: Making Sense of the Great Lakes, taught by Prof. Dan Philippon (CLA) and Prof. Deborah Swackhamer (School of Public Health and Humphrey School).

Implementation ideas

- Refine the core aspect of the project with the existing set of courses, and integrate in other courses. We integrated this curriculum into one GCC course in Spring 2016 and, to varying degrees, is part of all four GCC courses during the current Fall 2016 semester.

- Expand the Studio concept for Fall 2016 to include sessions for four GCC courses, as well as students in other curricular and co-curricular programs.

- Continue the GCC end-of-semester workshop.

- Adjust the quantity of KTI content to fit instructors’ needs: where possible, integrate further, and where KTI is competing with other priorities, reduce the number of hours devoted to KTI.

- Increase internship opportunities for students to continue work past the course.

References

Cheng, R., Schively Slotterback, C., et al. “Grand Challenges—Curriculum. Report of the Strategic Planning Workgroup University of Minnesota Twin Cities.”

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participation of a broad group of instructors essential for implementing this project. The instructors in the three courses that participated in this pilot included Prof. Vincent deBritto, Prof. Jason Hill, Prof. Cheryl Robertson, and Prof. G. David Tilman. Prof. Jim Toole developed the evaluation framework, facilitated feedback, and summarized the results. Institute on the Environment Managing Director Lewis Gilbert provided strategic advice on the project. In addition, Prof. Bill Arnold and Prof. Elizabeth Wilson were part of the original proposal team and advised on the early formation of the project. Finally, we are grateful for project funding from the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment and the University of Minnesota’s Center for Educational Innovation.

1Like a GCC course that covers a myriad of topics and their complex interactions relative to the grand challenge at hand (the vertical part of the “T” in this visual), the KTI likewise introduced a suite of capacities necessary for acting on these challenges (the horizontal parts of the “T”). Clearly a one-credit class (or equivalent) cannot begin to cover all trans-disciplinary capacities required to meet a challenge in any significant depth, as each is a discipline in and of itself. However, the intent was to introduce these skills so students could gain basic competency, apply these skills to the problem at hand, and most importantly, gain awareness of how to use these skills to tackle big projects in the future. The “Core GCC Course Design: Interdisciplinary grounding in a particular grand challenge” represented here is an example from GCC 5003: Seeking Solutions to Global Health Issues.

2An illustration of a student team’s path from a general interest in a problem to a refined proposal for taking action. The structure of the Knowledge to Impact co-curriculum relies on techniques from design thinking, organizational development, and communications. While proposal development is cyclical, relying on multiple iterations based on feedback, ultimately teams must consider questions outlined in the figure.