53 The Very Hungry Dino- Instructor Guide

Dinosaur Physiology

Everybody poops! But did dinosaurs poop like people or like birds?

Created by K Lupori, S Ramirez, and L Satterfield; members of the University of Minnesota veterinary class of 2027

Instructional guide

This unit is designed as an introduction to the avian (and dinosaur?) digestive system. The lesson is aimed at teaching how food travels through gastrointestinal (GI) tract, avian GI tract function, and the differences in GI tracts and diets between species. It should also reinforce dietary differences among species, particularly carnivores, herbivores and omnivores.

Intended grade level

- This is designed for 3rd-4th grade students

- Students should already understand how individual units (i.e organs) make up a system

- Students should have familiarity with the parts of the human GI tract: esophagus, stomach, intestines

- Students should be aware of dietary differences between species

Minnesota State Standards:

4.2.1 Students will be able to read and interpret multiple sources to obtain information, evaluate the merit and validity of claims and design solutions, and communicate information, ideas, and evidence in a variety of formats.

3L.4.2.1.1 Obtain information from various types of media to support an argument that plants and animals have internal and external structures that function to support survival, growth, behavior, and reproduction.** (P: 8, CC: 4, CI: LS1)

Student learning objectives

- Students will be able to compare and contrast the similarities and differences between GI tracts of humans, birds, and dinosaurs

- Students will be able to illustrate the flow of food down the GI tract

- Students will be able to describe the roles of the crop, proventriculus or stomach, and the gizzard

- Students will be able to explain the terms carnivore, herbivore, and omnivore. Apply these terms to birds, mammals and/or dinosaurs

Lesson background

The overall function of the digestive system is to breakdown ingested food into nutrients that can be used for energy in the body, but gastrointestinal (GI) tracts can differ slightly between species. Dinosaur GI tracts are assumed to be similar to avian GI tracts due to the presence of gastric pellet fossils, which in birds are formed by indigestible material that was ground down in the gizzard.

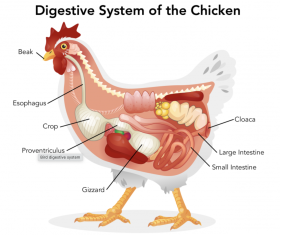

The avian GI tract begins with the mouth, which is bounded by the beak. Bird have a choanal slit in the roof of their mouth that connects the sinuses to the trachea. The choanal slit is lined with papillae, that help grab things and move them to the back of the mouth. The food then travels into the bird’s esophagus. The esophagus is the tube that connects the mouth to the crop. The main function of the crop is food storage. The crop allows the bird to store food that is consumed quickly, so as to decrease the time and susceptibility to predators the bird faces when eating. The food can then be digested at a later time. Next, the food travels to the proventriculus, which is what we would think of as the “true” stomach of the bird. This is where secretory digestion occurs. The proventriculus secretes hydrochloric acid, which converts pepsinogen to pepsin and enables digestion of proteins. Next the food travels to the ventriculus or gizzard. This is important in our comparison to the dinosaur GI tract, as it was likely present in Jurassic species and is also present in crocodilians. The gizzard contains two smooth muscle bands and this helps contribute to its function: grinding and crushing food. Many modern day birds also ingest rocks (gastroliths) or grit that also end up in the gizzard and are used to help crush food. Gastroliths have been found in the abdominal cavity of sauropod dinosaurs, further suggesting the presence of a gizzard. Next, the food will pass into the small intestine. The role of the small intestine is both fluid absorption and enzymatic nutrient digestion and absorption. Next the bird has paired ceca. The function of the ceca is water absorption. Microbial fermentation also occurs in the ceca. Next, the digested food material goes to the colon, which is short in birds and is the site of water absorption. Last is the cloaca, which is the end of the urinary tract, digestive tract, and reproductive tract.

Lesson Format

This lesson should take about an hour to complete.

This could be a small or large group lesson. Instructor guidance is needed to gain full value out of the lesson.

- This session starts with a brief discussion introducing the topic of digestion and its function. Ask students what they remember from previous sessions, a short review of human digestion. Students will listen to the recording of the “The Very Hungry Dino”. Video link. This link can be found on the student page of this lesson.

- This should be followed by a discussion that connects the story to what students already know about their own bodies, dinosaurs and/or what different animals eat. Students are encouraged to think about what dinosaurs diet may have consisted of and how the dinosaur GI tract is best suited to digest this diet compared to human GI tracts.

- The students will then complete their individual activity/knowledge check using the dinosaur coloring page. The goal is to add in the gastrointestinal tract parts. You may also want to use the coloring pages of girls, boys and birds. [Consider covering up or using white-out on the extra terms.]

Materials

- Smartboard or projector to watch the video

- Printed off copies of dinosaur coloring pages and human coloring pages

- Colored Pencils or Crayons

- Optional: books on the differences between omnivores, carnivores, and herbivores.

Assessment

- Students will play a game where they organize items into the order it would be found in a dino GI tract in a drag and drop manner

Common misconceptions and challenge points

- The differences between the proventriculus and the ventriculus may be difficult to understand at this level and comparisons/examples may be needed to help students better understand mechanical digestion (grinding) versus enzymatic digestion (acid).

- Dinosaur GI tract physiology is not fully known but has been assumed based on fossilized bone/teeth structures and fossilized feces. Like in birds, the fossil record has shown evidence of small stones or “gastroliths” that reside in the gizzard and aid in digestion of plants. There is some discrepancies in the research with what types of dinosaurs had gizzards, specifically for sauropods (herbivorous dinosaurs). For our purposes in this lesson, we assume the presence of a gizzard and focus on what is shared with avian and crocodillian species. The focus should be on identification of the GI tract function and digestive steps.

Further exploration

Other chapters within this textbook may be interesting for students. Some options can be found linked below:

Resources

- Varricchio DJ. Gut contents from a Cretaceous Tyrannosaurid: Implications for theropod dinosaur digestive tracts. J Paleontology 2001; 75: 401-406.