109 Doggy Diarrhea!

Timothy Magdall; Skylar Milne; and Natalya Wells

Doggy Diarrhea! Exploring Canine Hemorrhagic Gastroenteritis and the Relationship between Diarrhea and the GI Tract

The question

What is hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and how does diarrhea affect the normal function of the gastrointestinal tract in canines?

Learning objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Explain the general anatomy and pathway of digesting food in the canine gastrointestinal tract.

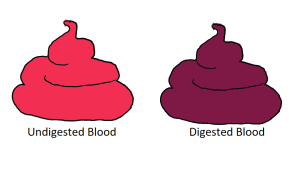

- Differentiate between digested and fresh blood in feces.

- Describe how diarrhea affects the normal function of the digestive tract.

- Identify clinical signs for hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and appropriate treatment for dogs.

Lesson

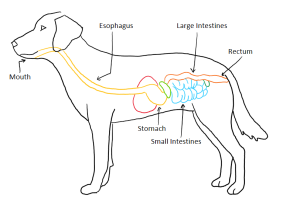

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a continuous passageway from the mouth to the anus. It is broken down into different sections that serve their own unique purposes:

- The mouth does the initial breakdown of the food (food is then called digesta once it enters the GI tract) via chewing (mastication) and enzymatic breakdown from enzymes in the saliva.

- The esophagus mainly moves the digesta from the mouth to the stomach.

- The stomach releases digestive enzymes and acid to breakdown the digesta.

- The intestines, the main focus of our lesson today, continue to breakdown the digesta and also work to absorb the nutrients and water from the digesta.

- The rectum stores the digested food until the body is ready to excrete it via the anus.

The GI tract is a very complex system and for most animals this system maintains itself and keeps a balance between breaking down food and absorbing the nutrients and water for the body to use. When things go wrong with the GI tract, the body usually reacts with either vomiting or diarrhea. Today’s lesson will touch on a disorder that can occur in dogs (and on the rare occasion, some cats) called hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, but first let’s take a closer look at the intestines and explore how their function leads to a dog having normal stools.

The Intestines

The intestines are broken down into two main sections: the small intestines and the large intestines. They both serve different, but equally important, purposes. The GI tract as a whole is very complex and multiple organs in the abdomen are there to serve the intestines and assist in their goals of digestion and absorption. For today’s lesson, we will not be going into detail of these different organs, but you should be aware that the liver and pancreas both release digestive enzymes into the small intestine and they both can play an important role in our dog with acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome.

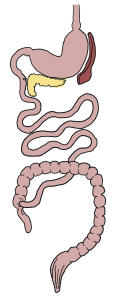

The Small Intestines

The small intestines are the first part of the intestines where the food goes directly after leaving the stomach. The main purpose of the small intestines is to mix the digesta with digestive enzymes and work to absorb excess water. The digestive enzymes break the food down, releasing the nutrients to be absorbed into the bloodstream. The small intestine is made of muscles that, when flexed and contracted, mix the digesta and move it along. This mixing action allows digestive enzymes to interact with as many parts of the digesta as possible, increasing their digestive potential.

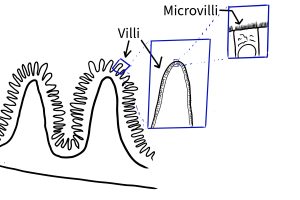

Absorption, the other main function of the small intestine, happens very efficiently due to the structure of the wall of the intestine and because of specialized cells that line the inner part of the intestine. The small intestine is lined with very small finger-like projections called villi that increase the surface area for absorption and work to move the digesta. Increasing the surface area is important because as surface area goes up, the amount of nutrients and water that can be absorbed goes up. The villi are made up of specialized cells called epithelial cells. These cells are what are actually taking in the nutrients and water from the digesta and they themselves are made up of little finger-like projections, called microvilli, that increase their surface area for absorption.

The epithelial cells are interspersed with another type of cell, called a goblet cell, which secretes mucus. Mucus plays an important role in the intestines as it protects the lining of the intestine from harmful microorganisms, acid, and digestive enzymes.

The small intestines are the longest part of the GI tract and are considerably longer than the large intestines. The digesta spends most of it’s time in the GI tract moving through the small intestines. The small intestines are broken down into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

The first section, the duodenum, the area where liver and pancreas enzymes are released into the small intestine. These enzymes play important roles in helping to protect the intestines from the acidity of the stomach and they also help breakdown fat cells.

The second section, the jejunum, is the longest section of the small intestine and is where most of the digestion and absorption of nutrients takes place.

The third section, the ileum, functions to absorb bile salts for reuse in further digestion, as well as further absorption of water and nutrients. After passing through the ileum, the digesta passes into the large intestines.

The Large Intestines

Once in the large intestines, the digesta, now called feces, continues on to be excreted via the anus. The large intestines are also broken up into sections: the colon, rectum, and anal canal. The function of the sections of the large intestines are largely the same in that they absorb any nutrients and water that were not absorbed by the small intestines. The lining of the large intestines is similar to that of the small intestines — the muscular lining of the wall of the large intestines also acts similarly. The large intestines are much shorter than the small intestines, so the feces spend less time here.

Case Study: Acute Hemorrhagic Diarrhea Syndrome

The lower GI tract is an incredibly complex system that, when working properly, allows the body to absorb the nutrients and water from the food and utilize them as it needs. The leftover food, devoid of nutrients, is excreted as feces and water, along with other metabolic wastes, are excreted through the urine. When the GI tract isn’t working properly, the system needs to react. Gastroenteritis is an umbrella term meaning inflammation of the lining of the stomach and the intestines. A hemorrhage is the term for a loss of blood from the body. Putting these two terms together give us the subject of our case study: hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, otherwise known as Acute Hemorrhagic Diarrhea Syndrome (AHDS). The symptoms of this disorder are vomiting, abdominal pain, lethargy (lack of energy), dehydration, and most notably, bloody, mucoidal diarrhea (many times it is described as looking like raspberry jelly).

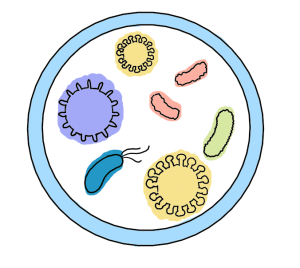

The exact causes for AHDS are unknown but it is theorized that dysbiosis may be a major contributing factor. Dysbiosis is a condition in which the normal, healthy gut bacteria in the intestines is overtaken by problematic, harmful bacteria. The main bacteria thought to be the cause in AHDS is Clostridium perfringens. The normal gut microbiome live in the mucus lining of the intestines along the villi and the healthy bacteria play a vital role in synthesizing vitamins, nutrients, and helping to breakdown food.

There are a number of ways that dysbiosis can occur: if the dog eats something that it doesn’t normally eat or if it eats something that it’s not supposed to (often times things that are not edible) are often two major reasons that are given for the instigator. Ingesting foods they’re not used to or ingesting inedible objects does not always lead to AHDS. Some dogs may develop no symptoms, some may develop mild cases of diarrhea — symptoms may last for a few days and clear on their own, or they may progress to AHDS. It all seems to depend on how the individual dog’s body reacts to the situation.

Diarrhea is often thought of as the body’s way of attempting to clear the intestines of something harmful. Physiologically, it is theorized that during AHDS, the body is reacting to the C. perfringens by excreting water and mucus into the intestines to try to restore the microbiome. During AHDS, the leakage of extra fluids into the intestines also brings with it red blood cells.

The color of the stool is clinically important as it can give the veterinarian a clue as to where in the GI tract the blood may be coming from. Red blood in the stools indicates that it is “fresh”, undigested blood — indicating the blood is coming from lower in the GI tract, closer to the rectum. Black material in the stool may indicate digested blood or blood that is coming from higher up in the GI tract, further from the rectum.

There is no cure or medication for AHDS so treatment is often symptomatic, meaning the veterinarian will try focus on treating the symptoms. The list of treatments may include administering fluids to make sure they are hydrated, administering IV nutrients (as many of these patients may not have an appetite to eat on their own), medications to protect the lining of the GI tract, pain medications, probiotics, and in some cases antibiotics may be used. These treatments are done to keep the patient comfortable, hydrated, and sustained nutritionally until their body is able to resolve the cause of the hemorrhagic diarrhea.

Activities

Gastrointestinal Tract Coloring Sheet

- Color each part of the GI tract a different color (excluding the crossed out terms).

- After completing the coloring portion, be sure to label each part of the GI tract, either on your image or in the game below!

Word bank: Esophagus, Liver, Stomach, Small Intestines, Large Intestines, Anus, Cecum

Assessment

After reading over the lesson and working on the activities, you may begin the individual short quiz. If you have any questions, you can ask your instructor. Please refrain from discussing with classmates while taking the assessment.

Further exploration

For students who are interested in veterinary medicine, below are some engaging resources and activities to support your learning:

- The Dog’s Digestive System – My Pet Nutritionist

- Systems – University of Georgia

- Resources For Aspiring Vets – Vet Set Go

- I want to be a veterinarian – VIN Foundation

Images created by the authors; creative commons for noncommercial use