3.6 Self-Care and Wellness

Certainly, counselors are subject to numerous unique stressors, challenges, and complex professional responsibilities within their practice. However, given the nature of the field, especially in the light of recent trends toward client-centered, humanistic, and empathic counseling, the ethical counselor is uniquely positioned to address these challenges while maintaining personal wellbeing and competent, compassionate practice with clients. The following section on self-care in counseling details the ethical obligation of counselors to engage in self-care. It provides guidance on general self-care strategies and those that have been evidenced to serve as protective factors for the stressors in counseling previously mentioned.

Ethical Duty for Self-Care

Self-care strategies are consistently mentioned within the literature as a front-line defense against professional stressors and impairment, ranging from harmful countertransferential reactions to compassion fatigue (Hayes et al., 2011; McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Velasco et al., 2023). Thus, keeping in mind the ethical obligation of the counselor to nonmaleficence and standard of evidence-based practice within the field (ACA, 2014; NAADAC, 2021), it follows that if self-care strategies are evidenced to reduce harm to clients, the ethical counselor is obligated to engage in them.

The ACA (2014) Code of Ethics directly addresses the topic of self-care, stating that:

“Counselors engage in self-care activities to maintain and promote their own emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing to best meet their professional responsibilities” (Section C, Introduction).

And the NAADAC (2021) Code of Ethics supports this notion as well:

“Providers shall engage in self-care activities that promote and maintain their physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing” (Standard III-18).

This being said, the need for self-care in counseling transcends the rigid application of ethical codes and clinical implications; it is also a recognition and respect for the humanity of those who choose to enter the counseling profession and an aspect of professional practice that, when done correctly, will keep you in the field with the same passion that inspired you to embark on your graduate training for years to come.

Self Care Strategies

Personal Therapy for Counselors

When working to understand others’ internal worlds, an important yet often overlooked aspect is developing an understanding of one’s internal world and formative experiences. Self-awareness, as previously discussed, is an essential step in this direction. However, it fails to provide the numerous opportunities for interpersonal learning and objective reality testing gained in a fruitful therapeutic relationship. Undertaking one’s counseling provides foundational psychotherapeutic skills that will apply to future difficulties encountered in one’s own life and practice while also serving as a humbling experience mirroring that of future clients (Hayes et al., 2011).

It is our stance that personal therapy is a beneficial tool for all considering entry into the counseling profession, and though it may not be a required component of your training program, its use has been advocated since the dawn of counseling itself (Freud, 1937; 1964). It continues to be utilized by most mental health professionals to have a positive effect (Bike et al., 2009). A recent, nationally representative survey of mental health professionals found that roughly 84% have engaged in at least one episode of personal therapy across a variety of presenting problems, with the vast majority (92% of those who sought therapy) reporting some degree of life improvement (Bike et al., 2009). Though we have all likely internalized a degree of the societal stigma towards seeking mental health care that we are subsequently working to eradicate, it is essential to remember that a first step in doing so involves consciously rejecting the myth that we are immune to the psychological maladies we are working to treat.

Self Awareness, Self Compassion, and Optimistic Perseverance

While many specific self-care strategies will ultimately be specific to the individual and crystallized only after thorough self-exploration, a few guiding principles are helpful to keep in mind when working to cope with balancing personal and professional stressors. Our continued emphasis on self-awareness throughout this chapter was intentional. Exercises such as mindfulness and self-reflection are continually reflected in the literature as a means of proactively coping with and treating phenomena such as harmful countertransferential reactions, burnout, and vicarious trauma (Hayes et al., 2011; McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Yang & Hayes, 2020). Though reflecting on every prompt we present consciously may feel tedious, fostering a curious and reflective practicing style will be instrumental in maintaining a healthy, ethical practice as a future clinician.

Self Compassion

Self-compassion is a core psychotherapeutic skill taught clients throughout most long-term counseling relationships. It assists them in reality-testing the feasibility of foundational cognitive schemas. Judging the realism of personally and interpersonally imposed demands on one’s time and ability is essential. Often, among counselors experiencing a great deal of personal and professional stress, it is not uncommon to reject the self-compassion they preach. Early writings in the field may have set this precedent, implying the counselor must have capabilities that exceed that of the average person (Freud, 1937/1964), and this notion is only further complicated by the lofty personal and professional goals held by many ambitious and aspiring counselors. A telltale warning sign of burnout in colleagues is using phrases implying personal failure and responsibility, such as “No matter what I do, they just do not seem to be getting any better!” or “Can’t they see that their substance use is killing them?” Sometimes, counselors compensate for this hopelessness by extending their boundaries and attempting to “take responsibility” for the client’s actions.

In contrast, others may start taking on an even more significant caseload to compensate for those they cannot “save.” It becomes apparent that actions such as these only serve to further the problem and consciously reject the fundamental notions of self-compassion central to maintaining healthy boundaries and a well-balanced sense of self. As counselors, we strive to foster autonomy in the counseling relationship, which also means accepting that we cannot force our clients to change. Maintaining a healthy level of self-compassion also requires accepting our limits, both as counselors and as people, which can often mean accepting challenging notions such that we may not be able to help every client we come across or that there are fundamental limits to the amount of professional work we can do in a week. Above all else, it is essential to remember that we are human beings, just like our clients. We have limits, make mistakes, and need ample personal and social support of our own to continue in the difficult work that we do.

Optimistic Perseverance

In certain professional settings, perceiving positive change arising from your work with clients may become difficult. This sentiment may be widespread in minimally funded agency settings, where structural inequities in our society are often perceived as barriers to enacting meaningful change (Schaufeli et al., 2009), or in mandated addiction treatment centers, where return to use will often occur multiple times before a pattern of stability is reached. Prolonged exposure to these sentiments without positive recontextualization puts counselors at strong risk for feelings of burnout and hopelessness (Maslach et al., 2016).

A seminal study by Medeiros and Prochaska (1988) investigated coping strategies among practitioners working in stressful situations and found that maintaining a sense of optimistic perseverance was associated with a greater self-perceived ability to cope with stressful situations more so than any other strategy examined. Optimistic perseverance is maintaining a positive, humanistic outlook while continuing to work diligently at a given task. As counselors, we can begin to foster a sense of optimistic perseverance by engaging in appropriate self-care, social justice, and advocacy work and consciously reflecting on the core beliefs underlying contemporary counseling approaches such as client-centered care and motivational counseling.

Self-care is an essential prerequisite for optimistic perseverance. To actively change our outlook and continue working hard in our careers, we must have the psychological energy to do so. An essential component of fostering this energy, vitality, and excitement for our careers is laying a foundation of self-care that promotes it. Part of why stressors such as burnout are so pervasive and, at times, lasting is that they sap our energy to engage in positive change without ample time for healing.

In addition to this, engaging in social justice and advocacy efforts, especially when confronted with seemingly insurmountable structural obstacles, is an excellent means of fostering a sense of agency that one is making the societal changes necessary to make the world a better place for their clients (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Activities such as getting involved in local social or political causes you are passionate about or joining a local board or committee are significant first steps in putting yourself on the front lines where you can see yourself enacting positive change.

Finally, working to truly and wholeheartedly reflect on the principles underlying contemporary approaches to counseling can be instrumental in creating an internalized sense of optimism. Though messages of cynicism may be some of the most prominent in specific workplace and societal settings, the principles that guide us as counselors are not. Consider notions such as those put forth by Carl Rogers (1957) and Miller and Rollnick (2013) as they describe the principles underlying client-centered therapies.

- Humans are inherently good and trustworthy people working to live in harmony with one another.

- Every person has intrinsic worth and potential.

- Every person has the right to make their own informed choices in light of their particular circumstances.

- As counselors, our work exists to serve our clients and meet their needs, whatever those might be.

- Clients are the experts on themselves and their own personal worlds.

- Everyone has their own inherent strengths, resources, and motivations for change.

- The counseling relationship is an equal partnership.

- Motivation for change already exists, it simply needs to be evoked.

Reflecting on the following, you may already hold many of these beliefs. Perhaps they drew you to the counseling profession in the first place. Let them continue to guide you in your practice, and consciously reflect on their meaning and implications in the face of professional difficulties or messages of cynicism that you encounter. In doing so, you can consciously work to keep the philosophy, compassion, and optimism that brought you to the field alive and well.

Working Towards Holistic Wellness

Though self-care is an essential tool for the counselor to keep in mind, the counselor may be limited in understanding what it means to cope effectively and flourish in all domains of life. Discussing self-care as a coping mechanism implies a degree of reactivity. In contrast, effective coping, especially in the face of the often emotionally demanding work of counseling, requires a proactive and holistic approach. This concept of holistic well-being in all life domains is often referred to as wellness.

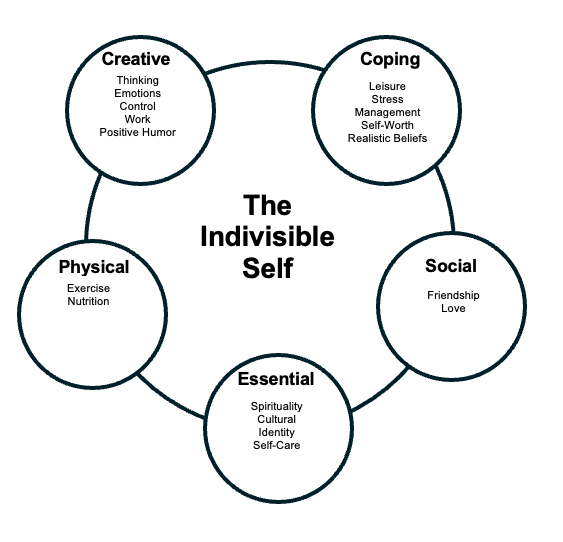

One of the most comprehensive and empirically supported approaches within the psychological literature is “The Indivisible Self,” as identified by Myers and Sweeney (2004). Guided by the individual, humanistic psychology of Alfred Adler and Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1999) bioecological model, “The Indivisible Self” model identified 17 factors contributing to holistic wellness across five domains of life: The physical self, essential self, social self, coping self, and creative self (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). We discuss personal wellbeing through the lens of this model below.

The Essential Self

The essential self comprises factors such as spirituality, self-care, gender identity, and cultural identity (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). These core aspects of our person also act as the lenses and frameworks through which we understand the world. In this context, self-care connotes an active desire to promote personal longevity and contentment in one’s life rather than a reactive means of coping with adversity.

Strategies for cultivating the essential self might include:

- Attending spiritual or religious group events

- Reflecting on one’s personal sense of spirituality

- Attending local community or cultural events

- Engaging in behaviors that promote longevity, such as regular exercise, healthy eating, and medical care.

- Advocating for the welfare and representation of persons with shared cultural and gender identities or for those whose identity groups are afforded more societal privilege, joining in advocacy efforts for other marginalized populations.

The Physical Self

The physical self involves promoting the wellbeing and longevity of one’s body. It consists of two subfactors: exercise and nutrition (Myers & Sweeney, 2004).

Strategies for cultivating the physical self might include:

- Prioritizing sleep hygiene

- Avoiding a sedentary lifestyle. Especially in the context of professional work, this might include standing up to stretch or walk between sessions or taking routine breaks while working on a lengthy project.

- Eating a balanced diet.

- Engaging in routine preventative care such as regularly brushing one’s teeth, taking prescribed medications, or moisturizing.

- Seeking routine preventative, medical, dental, and optical care.

The Social Self

The social self comprises friendship and love factors (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). This domain of functioning emphasizes establishing close and caring relationships with one’s friends and family (The term family, in this case, refers to both one’s family of origin and family of choice).

Taking care of the social self might involve:

- Taking time throughout the week to spend quality time with friends.

- Finding balance within one’s school and work life to spend time with family and take care of family responsibilities.

- Making proactive and assertive attempts to stay in contact with one’s family of choice, especially when geographically distant.

The Coping Self

The coping self is the domain of holistic wellness most commonly associated with self-care. It includes leisure activities, a sense of self-worth, realistic beliefs, and stress management (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). This domain is focused on finding healthy ways to approach and manage various life stressors and on continually growing and flourishing in the face of adversity.

Cultivating the coping self might look like:

- Attending personal therapy

- Keeping a balanced and realistic workload (We recognize that this is easier said than done in graduate training, but it will serve you incredibly well later in practice!)

- Reflecting on adversities you have encountered and overcome.

- Practicing self-compassion.

- Making time for hobbies or fun activities throughout the week. If you cannot readily identify personal hobbies, this could involve exploring new activities and seeking new experiences.

The Creative Self

The creative self comprises emotions, control, work, positive humor, and thinking (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). The factors encompassing the creative self function to shape and affect all domains of our lives, and thus, health in these domains is an essential foundation on which much of subsequent wellbeing is based.

One might cultivate the creative self by:

- Setting healthy boundaries regarding what is in and out of one’s control.

- Advocating to create a supportive work environment or finding a place of employment more conducive to one’s wellbeing if this becomes impossible.

- Examining one’s use of humor as a means of coping to ensure it is done healthily without sending negative messages to oneself or others.

- Examining one’s foundational patterns of thinking. Are they healthy and realistic ways of looking at the world? If not, how might things be examined more healthily?

- Seeking self-knowledge through journaling, art, or other reflective pursuits.

Systems Level Contexts

You may have noticed that the diagram (Figure 3.1) includes four systems-level contexts emphasizing local, institutional, global, and chronometrical systems (Myers & Sweeney, 2004). These systems-level influences were included under the recognition that organizational and systemic influences will ultimately impact individual wellness (and, conversely, that the individual impacts their environment). Factors such as current events, social trends, and systemic inequities may cause shifts in what is necessary for a person to achieve wellness and the ease at which it can be achieved. Similarly, including the chronometrical system guides us to consider that our wellness needs may change over time depending on our developmental stage and shifts in contextual factors.

The preceding section provided a very brief introduction to the concept of wellness, and while detailing just how one might achieve wellness would likely require a textbook of its own, we hope that this section spurred some thought about holistic self-care and how you might achieve wellness in your own life. The key takeaway we hope you draw from this portion of the text is that to maintain vitality in the profession, efforts to cope and flourish in one’s personal life must be proactive and holistic rather than arising in response to moments of stress or burnout.

Key Takeaways

- Counselors have an ethical obligation to engage in self-care, as it supports personal well-being and ensures the ability to provide competent and ethical client care.

- Strategies like personal therapy, mindfulness, self-compassion, and optimistic perseverance are effective tools for managing professional stress and maintaining a healthy counseling practice.

- Holistic wellness, encompassing the physical, essential, social, coping, and creative domains, is vital for sustaining personal and professional vitality.

- Proactive and holistic self-care prevents burnout, fosters resilience, and aligns with the humanistic principles underlying counseling practice.