10.4 Informed Consent with Adolescent Clients

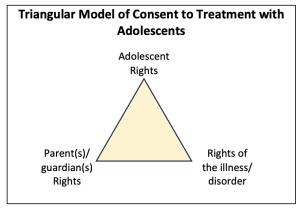

Counselors have an ethical and legal duty to obtain informed consent from their clients, which marks the initiation of their professional relationship (Ford-Sori, 2015). Koelch et al. (2015) posited a triangle-shaped model to help counselors navigate consent to adolescent treatment (depicted in box 10.3). The counselor is asked to balance the adolescent’s rights, the rights of their parent(s)/ guardian(s), and the rights and needs of the illness (Koelch, 2010). Sometimes, the presence of mental illness and substance use can limit insight and impact the person’s ability to act in their best interest (Koelch, 2010). In these cases, this does not justify depriving them of liberties or services, and the counselor must use clinical judgment to promote access to help in the context of safety concerns to themselves or others (Koelch, 2010). If treatment is necessary or mandated, the counselor balances the other legs of the triangle by highlighting each party’s rights.

Box 10.3 Triangle model for navigating consent to treatment for adolescents (Koelch, 2010).

During informed consent, counselors share the proposed interventions, their overarching goals of counseling, alternatives, and the risks and benefits of each with both adolescent client and their parent(s)/ guardian(s) (English, 1990). They clarify confidentiality and its limitations, including mandated reporting and duty to warn (Koocher, 2003). With adolescents, counselors should also discuss circumstances, typically around safety concerns, that could warrant disclosure to parents. Adolescents have a right to know how the counselor would handle those situations, and best practice is to give the client the option of being involved in disclosing their concerns with parent(s)/ guardian(s). Informed consent practices were discussed in Chapter 7, so we will discuss further applications with the adolescent population throughout this section.

They also must clarify their role as the adolescent’s counselor to the client and their family, as this can become complex. They consider who their client is and how therapeutic work is built around that and communicate about this with the client and their family. The therapeutic relationship with an adolescent client differs from one with an adult. The client is a minor with legal dependency on third parties who are not engaged in the counseling (or, if they are, not in the same way) (Koocher, 2003). Adolescents usually have ingrained, often unconscious beliefs about authority figures that can be projected onto the counselor and impact the therapeutic relationship (Koocher, 2003). Due to age differentials, there is an even greater power dynamic at play with adolescent clients (Koocher, 2003). Counselors navigate autonomy development differently with adolescents who face legal and social restrictions. Counselors must conceptualize adolescent concerns and diagnoses differently, thereby leading to different treatment plans and interventions in their counseling work (Koocher, 2003). Overall, counselors take on a different role with adolescent clients and have greater responsibility for them. They must know relevant ethical (see below) and legal codes for counseling this vulnerable population (Koocher, 2003).

The ACA (2014) discusses this:

“Counselors inform parents and legal guardians about the role of counselors and the confidential nature of the counseling relationship, consistent with current legal and custodial arrangements. Counselors are sensitive to the cultural diversity of families and respect the inherent rights and responsibilities of parents/ guardians regarding the welfare of their children/ charges according to the law. Counselors work to establish, as appropriate, collaborative relationships with parents/ guardians to best serve clients” (Standard B.5.b.).

Similarly, NAADAC (2021) posits the importance of confidentiality when working with minors:

“Addiction professionals shall protect the confidentiality of any information received when counseling minor clients or adult clients who cannot provide voluntary informed consent, regardless of the medium, in accordance with federal and state laws, and organization policies and procedures. Parents, guardians and appropriate third parties shall be informed regarding the role of the provider and the limits of confidentiality in the counseling relationship” (Standard II-17).

How to Obtain Consent

Counselors must consult state laws to determine how to begin care with minors (Ford-Sori, 2015) legally. State laws determine who must officially sign the informed consent document, and the options are at least one parent who has legal custody (not physical), the mature minor client, or both the parent and minor (Ford-Sori, 2015). Counselors may need to ask for custody documents to confer legal guardianship, divorce decrees if applicable, or protective orders between parents (Ford-Sori, 2015). Counselors also consult state law to determine differences and exceptions for minors consenting to mental health and substance use treatment. More states have enacted laws that allow minors to consent without parents to their treatment for chemical health concerns (Ford-Sori, 2015). Laws contain more details around the age of consent and between hospitalization/ partial hospitalization versus residential versus outpatient services. There is a fair amount of ethical discord around the appropriateness of performing urine drug screening on young people without their consent, and counselors are asked to use their clinical judgment with client welfare in mind (English, 1990). For adolescents seeking mental health care, about one-half of the states allow mature minors to consent to outpatient services. However, consent guidelines for inpatient treatment are more stringent, with more parental involvement and potential for liability (English, 1990). In emergencies, minors can consent to their care to meet immediate needs, and the best practice is to obtain consent from family as soon as possible (English, 1990).

Key Takeaways

- Balancing the adolescent’s rights, the parent(s)/guardian(s)’ rights, and the needs of the illness guides consent in treatment (Koelch, 2010).

- Proposed interventions, goals, alternatives, risks, and benefits are explained to adolescent clients and their parent(s)/guardian(s), with confidentiality limits clarified.

- The counselor’s role is defined as the adolescent’s advocate, respecting legal dependency and fostering collaboration with families when appropriate.

- Adherence to state laws is essential for determining who signs informed consent, addressing custody arrangements, and exceptions for mental health or substance use treatment.

- Adolescent clients are involved in decisions about disclosures to parents, with client welfare and safety prioritized alongside transparency in family dynamics.