Chapter 9: Credibility

9.2 The Dimensions of Credibility

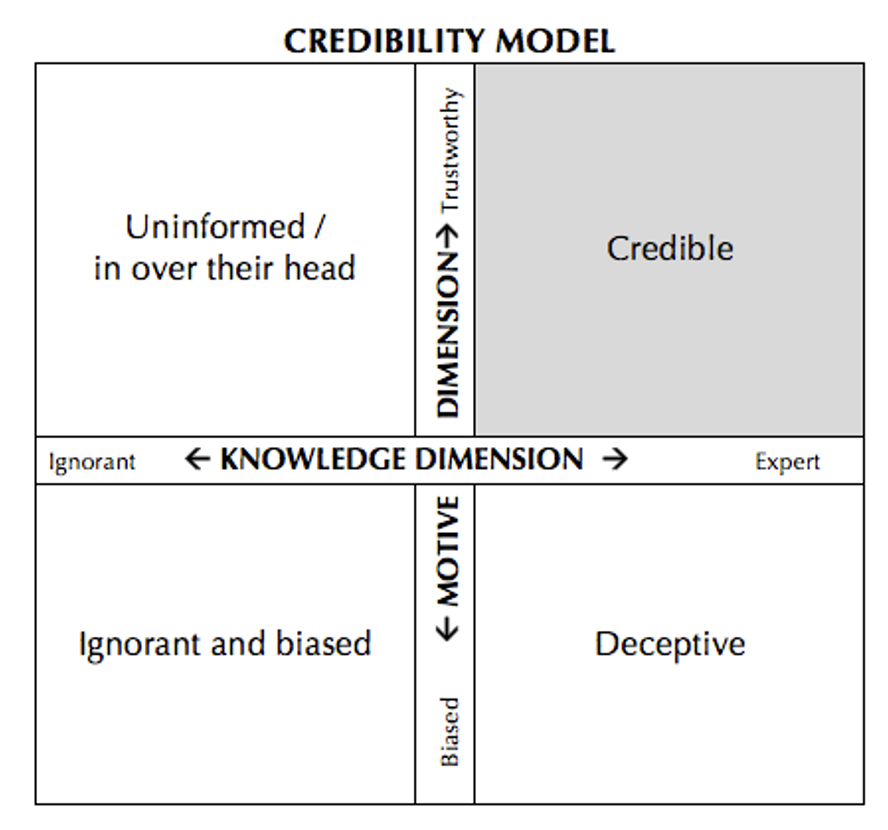

Credibility is not a simple concept: it was Aristotle who first proposed that it has two distinct and independent dimensions.[1] One dimension is knowledge or expertise, which revolves around the question “Does the source know what they are talking about?” This can mean someone who has become an expert in a field (i.e., a doctor), but it needn’t be as broad as that. An eyewitness who saw a car crash has expertise about what happened in that particular situation, even if they are not highly educated or have no history of studying collisions. Knowledge can come from education, experience, or both; some people become experts in a subject even without going to school for it. The meme in the previous section illustrates two types of knowledge: the doctor went to six years of medical school, but the patient knows their own body because they live in it.

The other dimension is trustworthiness or motive, which is all about why a person says something, and whether they can be trusted to be honest. Framed in the negative, the key question is, “Do they have a reason to lie to me?” This has to do with general factors like what kind of person they are — their moral character, history of behavior, and reputation — as well as specific questions about motive in a particular context. Even if they are generally an honest person, could they be lying now? (Think of how many murder mysteries involve a generally honest person being driven to cover up a crime out of desperation). One of the basic issues with trustworthiness is bias: either consciously or unconsciously, the person has a reason to want certain goals.

How independent are these dimensions? Think of when your car breaks down and you need to find someone to repair it. There are two basic questions you should ask about any mechanic:

- Do they know what they’re doing? If you have an electric vehicle, for instance, have they worked on them before?

- Are they trying to rip you off? Will they overcharge you or “fix” things that aren’t actually broken?

They could be an honest mechanic but incompetent (trustworthy but not knowledgeable), they could know everything there is to know about cars but still be out to rip you off (knowledgeable but not trustworthy), they could be incompetent and dishonest (neither dimension), or they could have both dimensions going for them.

Because either dimension can be trouble, calling someone “credible” means they must be in the gray cell in the upper right corner: the only kind of mechanic I would want working on my car.

But wait, there’s more! In the S-M-C-R model from Chapter 1, credibility can be a facet of the source (S) or of the message (M). Source credibility refers to all the things that make an audience believe a person: their educational background, work experience, position in the world, prior reputation, or endorsement by someone else (more on this below). When a police informant testifies in a trial, for example, there will naturally be a lot of questions about what kind of person they are and their motives for testifying. If the opposing lawyer succeeds in tearing apart the credibility of the witness, the judge or jury won’t believe what the witness says about what happened. To put it simply: if they don’t believe the person, they won’t believe the message.

On the other hand, sometimes the issue is what a person is saying, regardless of who they are, which is called message credibility. Perhaps you know someone you would describe as smart, but who also believes a conspiracy theory that you just don’t buy: you don’t have to change your mind about the person overall to conclude that they’re just wrong about that one thing. There are also situations where a person with generally low credibility says something that you do find believable, because the message itself makes sense.

To this point, the discussion has presumed that you know who the source of the message is, so your views of the person color your reactions to their message. What if you have no idea who the source is? If you start looking carefully at how many messages you hear or read in a day, you might notice that a large percentage are from unknown sources: a poster with no author’s name; an article you read without paying attention to the byline; a message posted online from someone with a cryptic username; a message that has a name attached, but it’s not a person you know anything about (think of the meme above from Kayla Fioravanti — did you look up who she is?). Aristotle probably didn’t spend much time talking to strangers, and he definitely didn’t read Reddit discussion threads, but strangers might account for 90% of the communication you receive every day. Without knowing the source, all you can do is look at the message itself and decide whether it’s believable.

To add to the confusion, let’s talk about the sleeper effect, the name given to situations in which people originally know where a message came from, but then forget. Hovland, Janis, and Kelley (the people who developed the five-step model of persuasion described in Chapter 6) researched this phenomenon, assuming that if people originally disbelieve a message because it came from a questionable source, they will never believe the message.

For example, your grandfather with dementia tells you he’s descended from Abyssinian royalty, right after telling you he was an opera singer and invented toothpaste, so you figure it’s the dementia talking and dismiss it. But then a funny thing happens: you remember the information, but forget where you heard it, so it becomes a free-floating tidbit in your head with no source attached. My head is full of such tidbits: I remember the message but forget the source. It can happen remarkably quickly; a student will say something smart in class, and five minutes later I’ll refer to the great point they raised but I’ve already forgotten who said it. Once the message gets disconnected from its source, a non-credible message that you didn’t used to believe because of where it came from now becomes a message you do believe because you “heard it somewhere.” So you end up telling someone you are descended from Abyssinian royalty because you forgot that it was an Alzheimer’s patient who told you that.

This is a huge problem in jury trials, where judges tell jurors they must base their decision only on the evidence heard on the witness stand. They try to keep people off the jury who’ve read a lot about the case in advance, but sometimes that’s impossible because there was too much publicity about the case and they don’t want the jury to consist entirely of people who have been “living under a rock” for the last two years. The judge may admonish a juror to forget what they heard or read before the trial begins and base their decision only on the testimony they hear in court … but this depends on the juror being able to remember where they heard each bit of information, and sorting out what a witness said from a rumor they heard from a neighbor.

This is also a growing problem on the internet, where things get spread around without attribution, or people put their name on something they’re reposting from somewhere else, and no one could possibly trace it back to its true origin. (For an investigative exercise, try this: Google the phrase “What happens to your body when you drink a coke.” You’ll probably run into an article that has been circulating on the internet for nearly 20 years, but good luck figuring out who the original author was).

Now we have four dimensions of credibility to consider: knowledge, trustworthiness, source, and message. But wait…there’s also the fact that organizational credibility can be as big a factor as individual credibility. Companies have credibility (or lack it), and whole industries also have or don’t have credibility (I already mentioned the surveys showing that the credibility of institutions like “the banking system” or “news organizations” is declining). All three levels — individual, company, and industry — borrow from each other, or hurt each other. For instance, if you, an individual college student, get admitted into Harvard University, people will make lots of assumptions about what kind of person you are based on the school you attend. (Or, if you got rejected from all the big-name schools you applied to and ended up at a “safety school,” that might hurt your credibility). Going the other way, if you achieve great success, you can bet that your school will brag about the fact that you went there. No wonder a high school in northern Minnesota changed their sign when their alumnus Bob Zimmerman (more commonly known as folk singer Bob Dylan) won a Nobel prize.

This “vicarious bragging” can extend to states and whole countries as well. Argentina, for example, is naturally going to bask in the glory of being the home of one of the greatest soccer players of all time (Lionel Messi), and his reputation helps the credibility of any other soccer player from Argentina. On the flip side, a region might try to live down the reputational harm from being the home of a serial killer or terrorist, or an individual might be embarrassed about coming from an area with a bad reputation.

All of this illustrates that credibility can be transferred from one party to another. If a person vouches for someone else, the first person is “lending” their credibility to the second person. This is what recommendation letters are all about: a person without much credibility on their own (a student) might get a person with credibility (a well-known professor) to write a letter saying how smart, motivated, and industrious they are. It’s also what political endorsements are all about: an organization such as a firefighters’ union or an individual such as the president might say “We back this candidate.”

- Technically, Aristotle identified three dimensions: expertise, trustworthiness, and good will, but most scholars (including myself) find that it works to combine trustworthiness and good will together. For a discussion of someone who disagrees with me and thinks goodwill should be considered a separate dimension, see McCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (1999). Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Communication Monographs, 66(1), 90–103. ↵