Chapter 9: Credibility

9.1 What Does It Matter Who Is Speaking?

The Dilemma of Deciding Who To Believe

I was on vacation in Canada when the hearing in my left ear suddenly quit. I could tell it wasn’t nerve damage because I could still hear myself chew, so I figured my ear must be just plugged up. I found a store that sold a foam promising to dissolve any ear wax, but it did nothing; one of my friends tried “ear candling” (placing a candle in your ear, wick side out, and letting it burn), but they didn’t know what they were doing and it ended badly. So I just had to wait until I got home, and the first chance I got, I went in to urgent care to see what they could do. Using a stream of water, the nurse succeeded in getting the wax out, and my hearing was restored. After thanking her, I asked: how could I prevent that from happening again? She wasn’t sure of the best prevention technique, but she was sure of one thing: “Whatever you do, never put a cotton swab in your ear!” Then she told me to wait for the doctor and left the room. When he came in, there wasn’t much to talk about, so I asked him that same question. His response? “I recommend you use a cotton swab in your ear a couple of times a week.”

I left the office shaking my head about those two totally contradictory messages and wondering which person I should put my faith in: the doctor, who has a more advanced medical degree, or the nurse, who probably has more hands-on experience? I had seen a few articles suggesting that the nurse was right and you shouldn’t put a swab in your ear, but who wrote them? What does it say on the box of Q-Tips swabs? “Do not insert swab into ear canal. Entering the ear canal could cause injury.” Maybe that was written by lawyers, and I didn’t have to pay attention to it as long as I was careful. Don’t most people use swabs to clean their ears? Why did the doctor recommend it? Maybe he doesn’t know much about ears, or maybe he knows more than others. Instead of swabs, maybe I should go back to ear candling, this time with someone who’s better at it. Most official medical websites say it doesn’t work, but there are plenty of “alternative healing” sites that swear by it. Who should I believe?

If you delve into the fields of nutrition and health, the “who to believe” question gets much worse. Investigative journalist A.J. Jacobs, in his 2012 book Drop Dead Healthy, spent a year trying to sort out what is healthy and what isn’t. After reading up on the thousands of new diets that come out each year, he jokingly announced his new health plan: consume lots of chocolate, wine, and coffee…all of which have been “proven” to be good for you. He also tried to figure out the correct answer to dilemmas like whether or not it’s a good idea to wash your hands, and whether you should run with high-tech cushioned running shoes or barefoot, and usually came away with the ambiguous conclusion that there are “two schools of thought.” In the more serious book Wrong: Why Experts Keep Failing Us — And How to Know When Not to Trust Them, David Freedman reveals the complete lack of agreement among medical professionals about what to do if someone’s heart stops: artificial breathing, chest compressions, abdominal compressions, or AED (automated external defibrillators)? After circling through the different organizations and individuals with contradictory views, Freedman ends with a sarcastic “Glad I was able to clear that up.”[1]

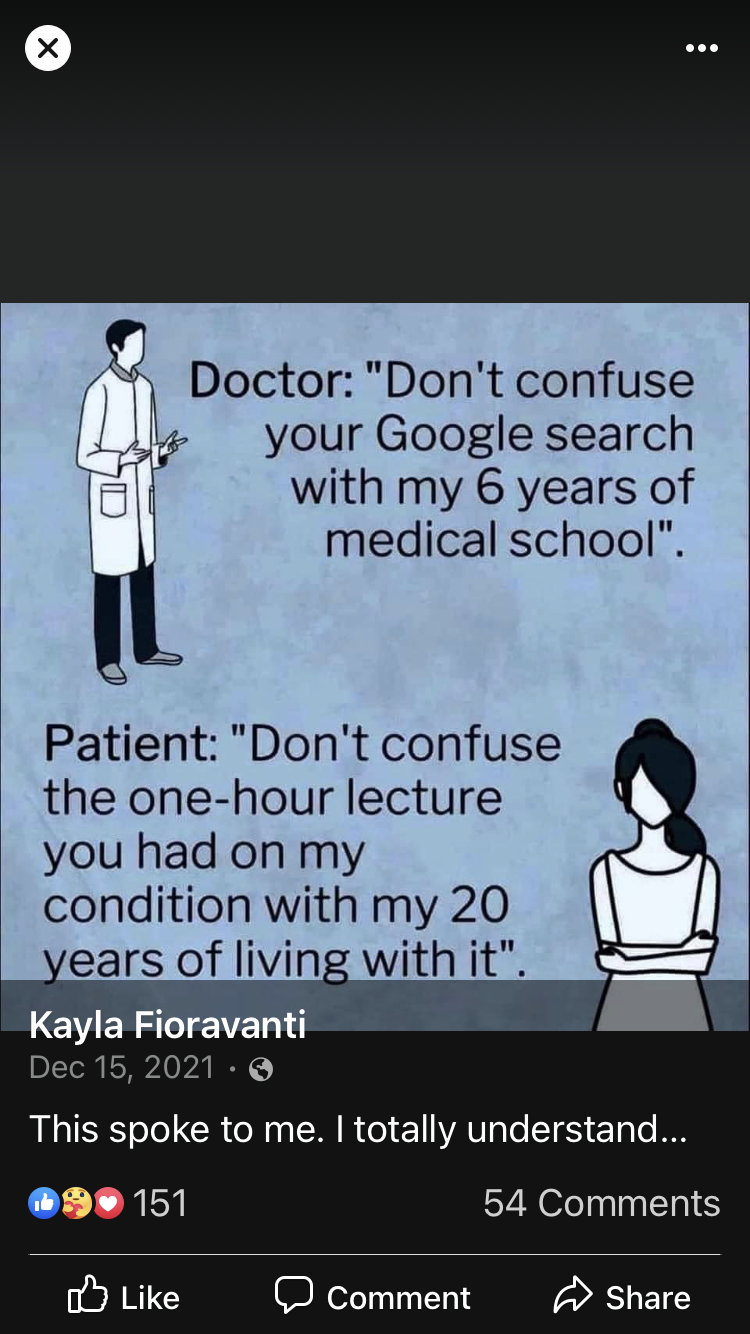

Even when the scientific community is united on one side of a controversy, it doesn’t seem to have much impact on the people on the other side; there are always reasons to doubt authority figures. Doctors get frustrated with patients who do a little googling and self-diagnose before coming to the clinic; everybody thinks they’re an expert now, just because they spent 20 minutes reading questionable websites. Yet the presumption that doctors are always right is obviously not true. They make mistakes frequently: 20,000 medical malpractice lawsuits are filed in the U.S. each year, and even Johns Hopkins University concluded that 250,000 Americans die annually from medical errors. So when I see memes like this, I can understand both sides of the equation:

These examples are just part of a much larger battle between official institutions and the common people, and the institutions are losing. The credibility of government, big business, news organizations, banks, schools, the medical system, and the police are all steadily declining. Virtually all world leaders are facing enormous credibility issues. Regardless of whether the approval numbers and survey results go up or down, this points to the dilemma that everyone faces every single day: deciding who to believe.

From my point of view as the receiver, it’s a decision that determines not just how I clean my ears or decide what to eat for breakfast, but what I do in every other aspect of life: Should I give that beggar money? What type of water filter should I buy? What source of news do I trust? Does my romantic partner truly love me? Different people use different methods to make decisions, but they can’t escape having to ask the question: Who should I believe? Some people lean toward the naive end of the scale, believing things they really shouldn’t and falling for scams (see the discussion of Reasoned Skepticism in Chapter 3). Others are cynical, automatically disbelieving and doubting everything, but taking that too far causes trouble and doesn’t make you many friends. If neither extreme is a workable philosophy of life, we’re stuck in the middle, having to make decisions about who to believe on a daily basis.

As a source, you have to be concerned with whether people believe you, and why. What is the point of saying something if people don’t believe it? It’s fascinating to me that credibility is a universal concern: the most powerful dictators in the world have to worry about their credibility just as much as a child denying that they ate a donut, even if the child is too young to speak. No one is immune from credibility concerns: business leaders, homeless people, coaches, teachers, military commanders, parents, social media influencers, and sales people rely on people believing them and taking them seriously. If you’re a college student, you’re on that list too — not just trying to convince your teachers that you’re a good student or that you really did miss that test because of food poisoning, but also convincing potential employers that you are hirable. After all, isn’t that the reason you’re in college in the first place: to show the world you know a thing or two?

- Freedman, D.H. (2010). Wrong: Why Experts Keep Failing Us — And How to Know When Not to Trust Them. Little, Brown and Company, p. 15. ↵