Chapter 8: Emotions

8.6 Specific Emotions

Fear

Since it has been so powerful in controlling people over the centuries, fear has received the most attention of all the emotions. When a presidential election approaches, you can expect the fundraisers to sound alarm bells about how high the stakes are and everything that could be lost. The parties may differ on what the fears are, but not on the fundamental strategy.

Fear has such a central place in politics that, whenever you hear any politician speaking, ask yourself, “What are they trying to make me afraid of?” and then, “Do I really need to be afraid of that thing?” Fear appeals also show up in health communication and nutrition, transportation and safety, religion, and news.

The basic structure of a fear appeal is simple: “Do (or Don’t do) Action X, because Consequence Y is dangerous.” How people respond to this message is not so simple, however. Some people see a value in facing danger and conquering their fears, so they’ll do the opposite of the recommended action in order to test themselves. Others respond by doubting the legitimacy of the danger, and dismissing the threat as a ploy: “Oh, don’t worry about that warning sign — they just want to keep us from having fun.” Reactions depend largely on perceived vulnerability: does the person think they are in actual danger?[1] This is partly a question of probability, and partly a question of timing. On the probability end, if a person hears “Vaping may cause lung disease,” they focus on the word “may” and conclude that it won’t happen to them. Perhaps the odds really are low, but even if they’re high, people are notoriously bad at understanding probability (see the discussion of shark attacks in Chapter 2), which is why the word “perceived” is crucial. In terms of timing, people might respond to an immediate threat, but it’s much harder to make them concerned about a threat that won’t show up for 30 years (“Even if there is a risk of lung disease, it won’t happen until I’m old, and I’ll quit before then”).

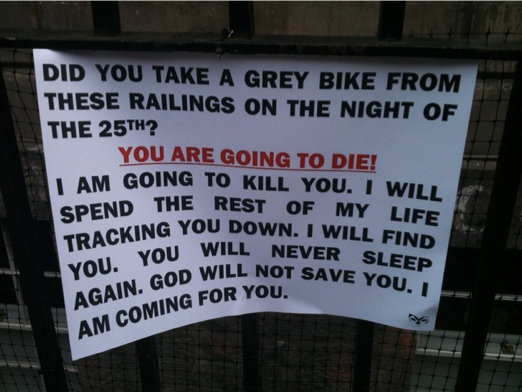

Here is a very blatant fear message posted in a city after someone’s bike got stolen:

If I was the thief, would that make me worry? Not a bit, because it all hinges on the victim being able to discover who took the bike, which doesn’t seem very likely. If the sign actually included the name of the thief, that would be a different matter.

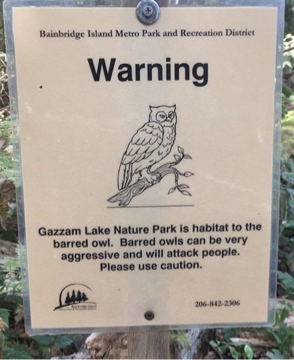

Fear appeals can also go wrong through their recommended action: “If you do Action X, it will make consequence Y go away.” This depends on the concept of efficacy: is that remedy actually effective?[2] The message might not say enough about what exactly you are supposed to do. “Be careful” is not very helpful if people don’t know what specific behavior that translates to. I was once hiking on Bainbridge Island, a lovely woodsy area outside Seattle that didn’t seem dangerous until I saw this sign:

I appreciated the warning, but would have also appreciated more advice about what to do if a “very aggressive” barred owl started dive-bombing me.

In contrast, when I was hiking through bear country in Montana, the warning signs did tell me what to do: keep making noise so you don’t startle a bear. It felt odd to talk loudly on a mountain trail, and it raised another question in my mind: “Is that really going to protect me?” In other words: does the recommended action actually stop the danger? Some dangers feel inevitable, and the precautions seem pointless. In the 1950s, American school children took part in “duck and cover” drills where they were told to hide under their desks in case of nuclear attack. If a remedy like hiding under your desk seems ineffective, what’s the point in doing it?

There’s one more way in which fear appeals can go wrong: if a warning involves asking people to do something difficult, heroic, or requiring will-power, some people just don’t feel capable of doing it. This is the issue with a lot of motivational posters and pep talks: they risk pushing people to the “I can’t do it” point. I remember being cautioned early in the COVID pandemic not to touch my face in public, but as soon as I thought of it, my face would immediately start itching all over until I gave in and scratched.

So, to recap, what happens if people are told about a danger but they:

- Don’t know what to do to prevent it,

- Don’t believe the remedy actually will prevent it, and/or

- Don’t feel capable of doing it?

They get fatalistic, and feel like they are doomed no matter what. Fatalistic people stop listening: they don’t take health precautions, they don’t vote, they don’t do anything you want them to do. Despite their power, then, fear appeals have to get a lot of things right, and there are many ways in which they can go wrong.

Anger

You can tell anger is closely related to fear because when you scare someone, they often respond by shouting at you instead of quaking in fear: “You almost ran me over, you idiot!” But not all anger is tied to a personal fear: you can get angry about something happening to someone else, such as a child being emotionally abused in a grocery store or a person spreading lies online. Anger is often related to the concept of justice, and it fills you with a desire to fix an injustice right now. Psychologists call it a “high-arousal” emotion, which also translates to the speed dimension — it has an urgency to it. This is both good and bad: it motivates people to action (see the discussion of the Yale 5-step model in Chapter 6, especially the last step), but can also make people do things they later regret because they didn’t fully think them through. This is where the “count to ten” advice comes from: letting that arousal die down a little can prevent trouble. Earlier I mentioned two weaknesses of emotional appeals in general — aiming at the wrong target, and the duration question — and both of them apply to anger appeals. Misplaced anger is a common phenomenon, and while some anger stays on a slow boil forever, other times it runs out before anything useful has been done.

Shame & Guilt: “Have you no decency?”

These basic emotions have many variations that are slightly different from each other, but have shared features. For example, although you may feel shame as a burning sensation somewhere in your body (implying that it’s a high-arousal emotion), guilt is generally a low-arousal emotion, and therefore works much more slowly than anger. How slowly? Well, in 2011 the news featured a story of a Sears store manager who received an envelope with a $100 bill inside it, sent by a man who admitted to stealing from that store 60 years earlier. If you try to “guilt” someone into doing something, in other words, don’t hold your breath: their conscience might bother them for decades before they act on it.

Speaking of conscience, guilt and shame appeals rely on the person having one, which not everyone does: some people really “have no decency.” (Embarrassment is slightly different, because you can feel embarrassed by everyone laughing at you, even if you don’t think you did anything wrong). They are also unpleasant emotions for most people, which means that a person might go through spectacular mental gymnastics to avoid them. Although it’s fairly common for employees to steal from their employer, for instance, they don’t seem to have any trouble rationalizing the theft: “It’s an evil corporation,” “They don’t pay me enough,” “I’m still a good person — I clean out the coffee pot without being asked,” “Everybody does it.” On the other end of the extreme, some people don’t avoid feeling shame, but dive deeper into it, getting into a “shame spiral” pattern that makes them act even worse.

Insecurity is a variant of shame that has been exploited in many areas of advertising, especially for beauty and hygiene products. The underlying message of many of such ads is “You are an unlovable, disgusting person right now because of your physical flaws [bad breath, unwanted facial hair, yellow teeth], but if you use our product, you’ll be lovable again.” This raises many ethical questions, and helps explain why so many people have body insecurity issues, but this approach has been undeniably profitable for many industries.

Pride

The other end of the shame scale is pride, which has also been profitable for many industries (such as those selling sports memorabilia and regional symbols like flags), and is a feeling people enjoy, unlike shame. Pride tends to be comparative in nature: it’s not just that you feel good about the state you live in, it’s that you can gloat about being better than the state next door. This explains why city, state, and country rankings are such a popular kind of content for online articles: everybody wants to see where their region fits in the list, and enjoys seeing their region show up in the top ten. A lot of pride is vicarious: there’s no real reason I should be proud of the fact that a popular actor grew up in my city (it’s not like I taught them acting classes myself), but I’ll take some unearned credit for it anyway. Appeals to identity, discussed above, are a powerful way to generate emotion.

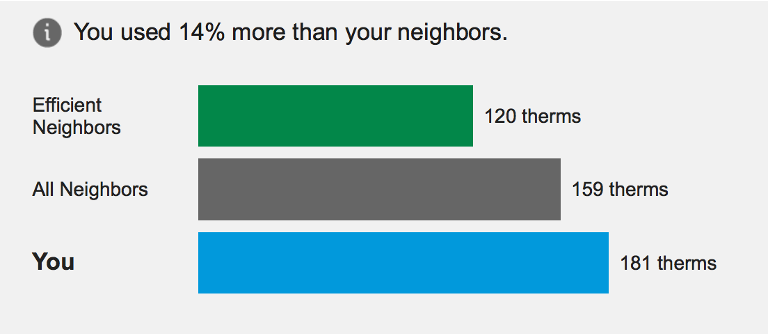

One intriguing form of pride appeal — or it could be viewed as a shame/guilt appeal — is the “comparison to your neighbors” emails I get from my power company:

I can do better!

Sadness

Sadness is the epitome of a low-arousal, low-speed emotion: if anger fills you with energy, sadness leaves you without energy (especially its extreme version, depression), and does a poor job of motivating people to action. Appeals to sadness are thus rare in public discourse, but it’s an emotion people feel anyway, and it has its value (as beautifully illustrated in the animated film Inside Out). One might situate grief near sadness, as Plutchik did in the second emotion wheel depicted above, but Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s famous model of the stages of grief emphasizes that sadness is just one of the stages, and high-arousal emotions like anger are part of the grief process as well.

Joy & Happiness

Speaking of Inside Out, it’s nice that Joy is the central character, the leader of the pack of emotions inside Riley’s head (if you haven’t seen the film, the main characters are five emotions — joy, anger, sadness, disgust and fear — in the mind of an 11-year-old girl). The pursuit of happiness is written into the U.S. Declaration of Independence, an “unalienable” right after life and liberty. So why haven’t joy and happiness appeared in many political messages since 1776? If you use another synonym, “contentment,” you can spot the problem: contentment implies being satisfied with exactly the way things are now, and not wanting to change anything. Going back to the Elephant-Rider-Path model, an elephant that has found its “happy place” doesn’t want to move, so happiness is not a motivator to change. Striving for happiness, on the other hand, is a good goal — and it’s nice to hear that studies on what makes us happy are one of the most thriving fields of research in the social sciences.

- de Hoog, N., Stroebe, W., & de Wit, J. B. F. (2007). The impact of vulnerability to and severity of a health risk on processing and acceptance of fear-arousing communications: A meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 11(3), 258-285. ↵

- Witte, K. & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education and Behavior, 27(5):591-615. ↵