Chapter 7: Logic & Reasoning

7.4 Rebuttal: How to Respond to Opposing Arguments

“Everything that guy just said is bull**t! Thank you.”

That was the entire opening statement of new lawyer Vinny Gambini (Joe Pesci) in the 1992 movie My Cousin Vinny. The trouble is, it’s supposed to be an opening statement, not an opening argument (in the courtroom, you’re told to save the arguing for the closing argument), so the opposition objected and the judge ordered the argumentative parts stricken from the record. That means Vinny’s first ever opening statement officially consisted of just the words “Thank you.” Even if the first seven words had not been stricken, they hardly qualify as an effective rebuttal. How should one rebut instead? Odds are, you’ve been trying to figure that out ever since another child insulted you on the playground and you couldn’t come up with a snappy retort (or it came to you too late, which is called “treppenwitz” in German: a reply you only thought up on the staircase after leaving the room).

The earlier sections of this chapter provide clues about different ways you can respond to an argument, starting with the Toulmin concepts of grounds and warrants. As the Hitchens razor (cited earlier) indicates, some claims have no grounds to back them up (or you could say that the grounds are “because I said so” and the warrant is “I am a credible person”). In that case, the first response can just be asking “What’s your evidence?” or “How do you know?” Even if the other person has evidence, that doesn’t mean it’s strong, and you might take the opportunity to pick it apart.

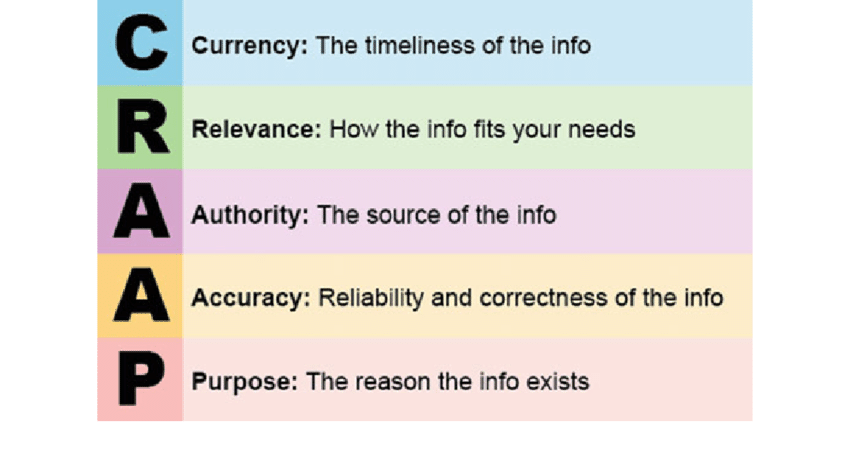

Questioning the Evidence: Evidence can take many forms, from hard statistical proof to “I just feel it in my gut,” and there are so many potential questions you could ask about evidence that the difficult part is thinking of all of them. Librarian Sarah Blakeslee came up with a handy — if somewhat rude — acronym to help you think of those questions: CRAAP.

Currency asks if the information is dated or current, and although some information we learned a long time ago is still accurate (water still consists of two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom), other information is obsolete or has been disproven since it was first introduced.

Relevance relates to the need to connect grounds to the claim. Sometimes the connection is weak or nonexistent. In arguments against banning certain types of weapons, for example, sometimes people cite stories of homeowners who defended themselves against an intruder…but with a different kind of gun than the argument is actually about. Some evidence isn’t at the right level — it works for an audience of middle school children, for example, but wouldn’t “fly” in a courtroom.

Authority is about where the information came from, which is sometimes difficult or impossible to track down. Can you pinpoint where the information originated, and if so, what are the credentials or organizational affiliations of the source? Is the source stepping beyond the bounds of their expertise, or are they a credible authority on that particular subject?

Accuracy is about the reliability and truthfulness of the information: what kind of evidence is it based on? (Remember, the distinction between “claim” and “evidence” is contextual, so “what’s the evidence for that evidence?” is a legitimate question). Did it appear in a source that is reviewed or refereed, such as an academic journal (where peers scrutinize an article before it is published), as opposed to a vlog where anyone can say what they want without having to verify it? Sometimes clues like spelling and grammar can tell you how meticulous vs. sloppy the source is.

Purpose looks at why the information exists in the first place, and if the source has a reason to promote a particular agenda or distort the truth. Does their point of view appear to be objective and neutral, or would you count it as opinion or propaganda?

You can’t always come up with definitive answers to all of these questions, but knowing the questions can help you attack questionable evidence. (For great examples of attacking evidence, watch the rest of My Cousin Vinny).

Questioning the Warrant is another approach to rebutting, and you can do it without examining the evidence. As the “smile vs. frown” example illustrates, even if it were true that smiling takes fewer muscles than frowning, there are still reasons that argument doesn’t make any sense. The first step, of course, is to identify what the underlying warrant is; since warrants usually remain unstated, this might take some skill. But if you can strip away the padding and get to the core argument, sometimes all you have to do is expose it to the light of day to show that it’s a weak argument.

If a company is arguing against a life-saving measure because it will hurt their business, for example, just saying “So profits are more important than human life?” can be enough. Another approach is to take the warrant a few steps further than the original person did. Remember the biker in Walmart: “Okay, if that’s true, then we should also….” (I remember a student making a rather forceful argument about why fighting in hockey is necessary and good, which made me ask, “So do you also think fights should be a central part of professional baseball and soccer too?”). Finally, you can argue for an opposing warrant. Warrants can sometimes be encapsulated in proverbs or common expressions. The thing about proverbs, though, is that there always seems to be an opposing one: “look before you leap” vs. “he who hesitates is lost,” or “many hands make light work” vs. “too many cooks spoil the broth.” Other warrants are derived from core values, but there is often an opposing value to consider as well: freedom vs. safety, equality and level playing field for all vs. accommodating special needs and circumstances.

If someone is proposing a particular plan or policy, there are many ways to attack the idea. Let’s take the example of Brexit — the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union in 2020. Opponents could ask: Is the plan really necessary, or is this a crisis that may resolve itself? Could the consequences of the proposed action be even worse than the current situation? Is this the right solution to the problem, or is there another way to address your concerns that would work better? What are the practical questions that need to be considered, such as: “What will it cost? Who will be in charge? Will it lead to new rules that can’t be enforced?” In the Brexit example, some of these questions don’t seem to have been fully considered until it was too late. On the other side, if you are proposing a plan and the opposition is putting up a fight about it, you can respond with: “Yes, my plan isn’t perfect but something needs to be done, and inaction is not a good option,” “Do you have a better plan?”, or “Great ideas are worth the cost.”

One last principle to keep in mind when responding to a counterargument is that it’s okay to concede some points here and there. Do you have to win on every point? If you don’t, will letting the other side win on a few points actually help your position? Toss them a bone (as long as it’s not your main argument). Sometimes you can even turn concessions into advantages. When the opposition wants to use an insulting name, for instance, some people respond by embracing the name (an example is the word “queer,” which started as a vicious insult and ended up being a preferred term by the queer community). This might require letting your ego back off a little bit, but ego can be a hindrance instead of a help in many situations.

Finally, my years of consulting with lawyers have taught me three valuable lessons from the courtroom that have carried over into other areas of my life:

- If you think the opposing side doesn’t have a legitimate case, you’re not ready for trial. I saw it many times: if you spend the night before trial making breezy jokes about how you’re going to wipe the floor with the opposition, you’re in trouble. Never underestimate the opposition, or play the Straw Man game on yourself (deliberately oversimplifying or misrepresenting their case to make yourself feel better). Finding out what their case is really about is a much wiser choice.

- Overstating your case, and being 100% certain that you are right about everything, is weakness, not strength. Witnesses who are absolutely sure of what they know are not credible witnesses. People respond well to the willingness to at least acknowledge limitations or consider opposing views. (SEE Chapter 9.4).

- Your best weapon is a question the other side can’t answer.

Even if you have no plans of becoming a lawyer or ever seeing the inside of a courtroom, these lessons can be helpful when you find yourself stuck in a conversation with a strongly opinionated relative at a holiday meal, shouting at opponents at a rally, or in a heated online discussion.

BOX 7.4: WHAT VIZZINI REALLY TAUGHT US

One of the movies from the 1980s with the most enduring popularity is The Princess Bride, featuring the memorable character Vizzini (played by Wallace Shawn). He fancies himself a genius, but his fate reveals otherwise. He and his two henchmen (swordfighter Inigo Montoya and giant Fezzik) have kidnapped the title character and seem to be getting away with spiriting her off to a foreign country when the mysterious Man In Black (Cary Elwes) catches up to them. After defeating both the swordsman and the giant, the Man in Black challenges Vizzini to a “Battle of Wits” involving poisoned wine. The Man in Black shows Vizzini the poison — tasteless and odorless “iocaine” powder — and turns his back to fill two cups, saying “Alright, where is the poison? The battle of wits has begun. It ends when you decide and we both drink — and find out who is right, and who is dead.”

Vizzini proceeds to show off his “dizzying intellect” by trying to deduce which cup has the poison in it. The trouble is, all he really does is think up a reason why it would be in his own cup, followed by a reason it would be in the other cup. They include syllogisms such as “iocaine comes from Australia. As everyone knows, Australia is entirely peopled with criminals. And criminals are used to having people not trust them, as you are not trusted by me. So, I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you.” Vizzini shifts back and forth, with each argument contradicting the previous one instead of building on it and each one riddled with fallacies, until he finally distracts the Man in Black and switches the cups. While he is gleefully declaring himself the victor, Vizzini abruptly keels over dead.

Logic is the process of combining assertions to reach a conclusion, and the study of logic begins with examining the assumptions that underlie the argument. Vizzini is full of assumptions, some quite far-fetched (only people who study sword fighting know that human beings are mortal?), but at least he puts on a show of examining his own premises. It’s not until after he’s dead that we find out which assumption he should have questioned but didn’t: that the poison was only in one cup. The Man in Black, it is revealed, spent years building up an immunity to iocaine, and put it in both cups. Vizzini called other people morons, but what made him a moron is that it never occurred to him to question the rules of the game, or notice that the Man in Black never said only one cup was poisoned (the closest he comes is that phrase “find out who is right, and who is dead”). When I show this movie in class, I freeze it at the frame where Vizzini is toppling over and loudly remind my students, “It’s the assumptions you don’t question that kill you!” If you get nothing else out of this chapter, at least remember that lesson.