Chapter 1: What is Communication?

1.1 Four Communication Scenarios

Four Communication Scenarios

Scenario 1. After doing a late-night run to a 24-hour grocery store, you drive home along a well-lit street. A car coming the other direction flashes their headlights at you, which leads you to check your own headlights and realize they aren’t on. You say a quiet “thanks” to that stranger, but the car has already passed.

Scenario 2. An elderly man approaches his wife and says “Have you seen my —” and she replies “It’s in your bottom drawer” before he even finishes the question.

Scenario 3. A young person watching television sees a celebrity in front of a bank of microphones and cameras, looking sad and saying “I am deeply sorry for what I said; I did not mean to use insensitive language or imply any disrespect toward any particular group of people. That is not who I am or what my values are, and I will never do it again.” The viewer rolls their eyes and says “What a liar! He doesn’t mean a word of it.”

Scenario 4. Sonja comes back from an auto body shop, her car freshly painted a bright turquoise, and pulls into her driveway. Her partner opens the front door and steps outside. Sonja gets an anxious look on her face, and asks, “Well? Do you like it?” Her partner does not change their expression or say a word, and simply turns around and walks back into the house. Sonja calls out, “I thought you’d love it! You said you hated the dull gray of our car, and this seemed to be your color.”

None of these scenarios is rare, yet they show the complexities of communication. In fact, whether they all qualify as “communication” is debatable: In the first scenario, no words were spoken, and the two people involved never saw each other’s faces or even knew who the other person was. In the second, a question was answered before it was even asked (at least explicitly). In the third, the celebrity’s message was heard but not believed, and their attempt to remedy a problem may have made it worse. And in the fourth, only one of the participants in the conversation said anything at all.

On the other hand, all four scenarios could indeed be called communication, perhaps even effective communication: in the first scenario, a simple message was conveyed quickly and it solved a problem; in the second, the elderly couple has become so efficient at communication that they don’t need to finish their sentences; in the third, one particular audience member might reject the celebrity’s apology, but millions of others could find it completely convincing; and in the fourth, the partner who didn’t say a word still got a message across through their silence and blank expression.

So is it more accurate to call the scenarios “communication” or “miscommunication”? The first one illustrates how simple an act of communication can be: a person can convey a vital message to a total stranger in a second, and the fact that the two people involved may not even speak the same language is not a barrier. The third scenario, in contrast, illustrates the opposite: that a carefully and deliberately crafted message reaching a large audience through technology may achieve nothing at all.

The lesson? Sometimes communication is very easy, and sometimes it’s very hard. Anyone who assumes that communication is a simple, risk-free process is bound to find out that they are wrong.

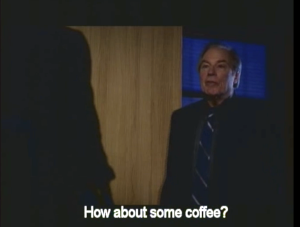

Let’s look at another example, from the television series Better Call Saul. In Season 2, Chuck (played by Michael McKean) is at his law firm early in the morning, and another lawyer Kim (Rhea Seehorn) startles him by coming into the office. They have this exchange:

Kim: It’s good to see you here.

Chuck: Yeah, I’m trying something new – coming in and working until 9:00. It’s easier before the place opens, without all the lights and the phones ringing. How about some coffee?

Kim: No, thank you.

Chuck: [awkwardly] Umm. Would you mind making me some?

What is happening here? Does Chuck think Kim, whom he has known for years, is only an assistant, not a lawyer? Is he an arrogant jerk who thinks that female colleagues are just there to serve him coffee? In fact, it’s because of a “condition” he has, something he refers to as a “sensitivity to electromagnetic fields” and that Kim is aware of. So Chuck has to add:

“I apologize. It’s just… I can’t do it myself… with the electricity.”

Interpreting “How about some coffee?” as an offer instead of a request is a simple mistake. Even highly educated people can get tripped up by ambiguous language like this, and it just takes a few more words to clear it up. Except that, in this case, it’s not entirely cleared up: Chuck explaining what he meant is not enough to convince Kim that he is not an arrogant jerk — she already knows what kind of person he is from many things he has done and said in the past, and this exchange is only a brief fragment of a conversation that has been going on for years. Communication, then, is not just about words: it’s about who the participants are, the relationships they have with each other, the context in which the interaction occurs, and how each person interprets the messages from the other.

In this case, however, we’re only looking at communication between two people. Much communication takes the form of an individual communicating to a group (small or large), or to a diffuse audience of millions across the globe. Communication may come from an organization, not an individual, and it may transcend not just geographic boundaries but also time: written messages, art, and architecture can speak to us from centuries past. Think of how often you read a message but have no idea who wrote it (because it is a written sign, or anonymously posted, or all you get is a username but can’t learn anything about the person). And from the other direction, many people broadcast messages to the world but, without sophisticated audience analysis techniques, they may not have any idea how many people receive the messages or who those people are.

Learning to communicate is not a simple task you can master in a day, like learning to convert a fraction to a percentage or to change the oil in your car. In many ways, you learned to communicate long before you started attending school (the home is sometimes called “the first classroom for communication”), and someone who never attended a day of school can do it alongside someone who studied it in college. In other ways, however, communication is a lifelong struggle, and there is always more to learn. You could compare it to cooking: you may have gotten the hang of making toast or boiling an egg early in life, but there is always more to learn, and even if you consider yourself a good chef, that doesn’t eliminate the risk of a meal going disastrously wrong. Is it worth studying cooking in college? For many people, the answer would be no, and they can get by on their rudimentary skills or rely on others who are better cooks. Others find it useful to take many cooking classes, and the more they study, the more they realize they need to learn.

In a similar vein, one could debate the value of studying communication in college. Some may think it’s something they’ve already mastered, so taking a course in communication seems as superfluous as taking a course in walking. But consider this: if you ask companies — regardless of industry or country — what skills they are looking for in new employees, their answers are remarkably consistent: they are looking for communication skills. If those skills were easy to acquire and universal, the companies wouldn’t list them as a valuable asset (it would be the equivalent of starting a job notice with the phrase “Applicants must be able to breathe”).

BOX 1.1: What Nineteen Surveys Say About the Value of Communication

The University of Kent produced a summary chart of “The Top Ten Skills That Employers Want,” based on surveys conducted by Microsoft, Target Jobs, the BBC, Prospects, NACE, AGR and other organizations. Even though it’s billed as a top ten list, I’ll include items 11 and 12 as well:

| Skill | Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VERBAL COMMUNICATION | 1 | Able to express your ideas clearly and confidently in speech |

| TEAMWORK | 2 | Works confidently within a group |

| ANALYZING & INVESTIGATING | 3 | Gathers information systematically to establish facts & principles. Problem solving |

| INITIATIVE/SELF MOTIVATION | 4 | Able to act on initiative, identify opportunities & proactive in putting forward ideas & solutions |

| DRIVE | 5 | Determined to get things done. Makes things happen & constantly looking for better ways of doing things |

| WRITTEN COMMUNICATION | 6 | Able to express yourself clearly in writing |

| PLANNING & ORGANIZING | 7 | Able to plan activities & carry them through effectively |

| FLEXIBILITY | 8 | Adapts successfully to changing situations & environments |

| COMMERCIAL AWARENESS | 9 | Understands the commercial realities affecting the organization |

| TIME MANAGEMENT | 10 | Manages time effectively, prioritizing tasks and able to work to deadlines |

| Other skills seen as important: | ||

| NEGOTIATING & PERSUADING | 11 | Able to influence and convince others, discuss and reach agreement |

| LEADERSHIP | 12 | Able to motivate and direct others |

I would argue that five of these 12 items — #1, 2, 6, 11 and 12 — are about communication. It’s perhaps worth noting that I found this survey on a subpage of the website of the Medical University of South Carolina, as well as on the site of Beijing Foreign Studies University, suggesting that this list is valuable for people in a wide variety of industries and geographic regions.

This list lines up nicely with Forbes’ list of “11 Essential Soft Skills in 2024”, in which the first three items are Communication, Leadership, and Teamwork (see Chapter 16), and items #9 and #10 are Critical Thinking (Chapter 7) and Conflict Management (Chapter 17).

Here are 17 other surveys of valued workplace skills where “communication” is at or near the top of the list:

- Target UK’s list of “the top 10 skills that’ll get you a job when you graduate”

- Indeed.com’s “Top 11 Skills Employers Look For in Job Candidates”

- Monster.com’s “15 Examples of Soft Skills Employers Value”

- Jobscan.co’s “Top 10 soft skills employers want”

- GoSkills.com’s “Top 10 Skills Employers Want to See on a Resume in 2024”

- LinkedIn’s “LinkedIn 2024 Most In-Demand Skills”

- SkillArena’s “Top Skills Employers Are Looking For”

- The Muse’s “Top 10 Examples of Soft Skills Employers Want in 2024”

- GlassDoor’s “Top Skills That Employers Look For By Category”

- WayUp’s “Top 10 Skills Employers Want In An Intern”

- CNBC’s “The 10 most in-demand skills employers want to see on your resume right now”

- Pitman Training’s “Top 10 Skills Employers Look For – Key Skills for your CV”

- Zety’s “Top 10 Employability Skills”

- The Bloomberg Report’s “Job Skills Companies Want But Can’t Get”

- The National Association of Colleges and Employers’ “Key Attributes Employers Are Looking For on Graduates’ Resumes”

- National Network of Business and Industry Associations “Common Employability Skills”

- Business News Daily’s “Soft Skills Every Tech Professional Should Have”

This list was compiled in 2024: try it yourself and see what pops up in the #1 spot of what employers want. Has it changed?

The surveys summarized in Box 1.1 not only show the consistency of the value of communication skills in the workplace, but illustrate how many different kinds of jobs this applies to: not just jobs monitoring social media sites or managing salespeople, but jobs that some would consider purely industrial. Perhaps the most startling is an article called “What Aviation Employers Expect” that, like most of the 19 surveys in Box 1.1, lists “Good Communication Skills” as the top skill, but goes on to point out that “competence in the field” is not on the list. Sure, anyone who applies for an aviation job is expected to know how to fly an airplane, but the article stresses that this is not enough: if you’re not good at communicating, you won’t be a good pilot.

The academic field of communication studies, however, has always faced a conundrum: no one questions the need for a pilot to study aviation in school, but if they want to develop that “soft skill” of communication, where are they supposed to learn it? According to some people, the answer is “not in school”; communication as an academic discipline is met with skepticism, and sometimes considered a “joke major.” Why is there such a discrepancy between what employers want college graduates to know and what people consider valuable to study? One particularly harsh blogger in 2017 wrote “[A degree in Communications] is nearly worthless in that it won’t be of much use to you after college. It teaches you how to communicate effectively, a skill that anyone can learn quite easily without the need of professors or extra homework.”

The assessment that communicating effectively is “a skill that anyone can learn quite easily” would be news to the health officials who in 2020 struggled to keep the public abreast of developments in the COVID-19 pandemic and puzzled over how to convince people to adopt behaviors that would save their lives. It would be news to world leaders trying to achieve approval ratings higher than 50%, juries struggling to figure out how to get past disagreements and reach a unanimous verdict, parents puzzling over how to stop their child from swearing, advertisers working to draw attention to a new product, and advocates fighting to overcome societal problems without creating backlash.

That said, even people who teach college-level communication courses still struggle to communicate effectively, and I can’t promise that one textbook will teach you everything you need to know. My point is that communication is a field worthy of study, and this book is intended to be a starting point.