Chapter 12: Nonverbal Communication

12.4 Variables in Nonverbal Behavior Use

Why are simplistic guides about using or interpreting nonverbal behaviors unreliable? For several reasons:

Nonverbal habits are deeply personal. One person may cast their gaze downward most of the time while their best friend looks people in the eye whenever possible; one sibling is perpetually smiling while their brother looks grumpy all the time; a child goes up to just about anyone and hugs them while their parent is reluctant to hug even their own siblings. Instincts sometimes conflict with training, such as for a salesperson taught to shake customers’ hands vigorously or a politician learning to shout and pump their fist at rallies, though their natural inclination is to speak quietly and keep their hands in their pockets. Personal habits can derive from many external sources (your family upbringing, generation, past relationships, media, and training you’ve received) or internal personality traits.

Nonverbal behaviors depend on social context. Looking at one person’s behavior in isolation can blind you to the social dimension of nonverbal communication. People don’t always smile because they are happy; often it’s because they want another person to like them, or everyone else is doing it, or it just fits the situation. Even when it comes to things like arm and leg positions, people are often unaware of how much they imitate each other ; this is called “postural congruence”[1] or “mirroring.” Once I learned about it, I couldn’t unsee all the times I was in a group and at one point every single person had their hands intertwined behind their neck and their right leg crossed over their left knee; 15 minutes later, everyone had their hands folded on their stomach and their left ankle resting on their right . As far back as the 1960s, therapists have recommend this as a subtle way of establishing rapport with patients,[2] and salespeople picked it up as well. People instinctively wince when they see someone else experience pain, which Bavelas calls “motor mimicry.”[3] In short, nonverbal communication might not express how we feel so much as how we want to connect with others.

Rules governing appropriate behavior are many, and violating those rules can be more serious than violating rules of speech. Some of these rules are explicitly spelled out, others are left unstated; some are widespread, others are unique to a particular group. Touch, for instance, is an important means of communication, but the rules around the kinds of touch that are appropriate or inappropriate are serious, and you can get arrested for violating them. Even if there is no risk of criminal penalties, standing so closely to someone that you “invade their personal space” can cause discomfort and social difficulties, and different cultures have different guidelines about where the boundaries are (these have been studied extensively by the pioneering nonverbal researcher Edward T. Hall).[4]

Cultural variations can be wide, puzzling, and troublesome. Many travel guides warn you about gestures that mean different things in different countries . If you are going to Thailand, for example, and are unaware that showing the bottom of your feet to others is highly offensive, you could discover that rule the hard way. Author Rory Stewart walked across Afghanistan, and described a conversation he had with local tribesmen in someone’s home. That conversation was possible not only because he could speak fluent Pashto, but because, more importantly, he knew the vital importance of where people sit relative to the door, which is a reflection of their status.[5] Even within one country, such as the United States, cultural variations can have unfortunate consequences. Some Native American tribes, for example, consider direct eye contact to be defiant, and downward gaze is seen as more respectful—but if someone from that tribe is arrested and interrogated, the police might assume that their lack of eye contact means they are lying.

Some people have social-emotional agnosia. This is the inability to read facial expressions, tone of voice, and subtle bodily cues, which can be a symptom of schizophrenia or autism. Blindness and deafness also limit a person’s ability to pick up on visual or audio cues. On the expression side, there are numerous conditions that interfere with someone being able to send nonverbal signals ; you can’t, for instance, adopt the correct facial expression if you’ve had a stroke and can’t control some of the muscles in your face.

It may not be an exaggeration to say that everyone has some anxiety about their nonverbal skills . On the one hand, you were communicating nonverbally long before you uttered your first words, so you could say that the majority of the population is better at nonverbal communication than verbal forms, On the other hand, it’s easy to overestimate how fluent people are in this “language,” and you’ve probably had experiences with misinterpreted signals. You might find it fun to take a test of your ability to read nonverbals.

… or you may worry that you’ll fail that test.

Also keep in mind that nonverbal communication has an element of vulnerability . Expressions like “the eyes are the window to the soul” or “I can read you like an open book” can be scary ; what if you don’t want to be an open book?

BOX 12.4: Expectancy Violations Theory

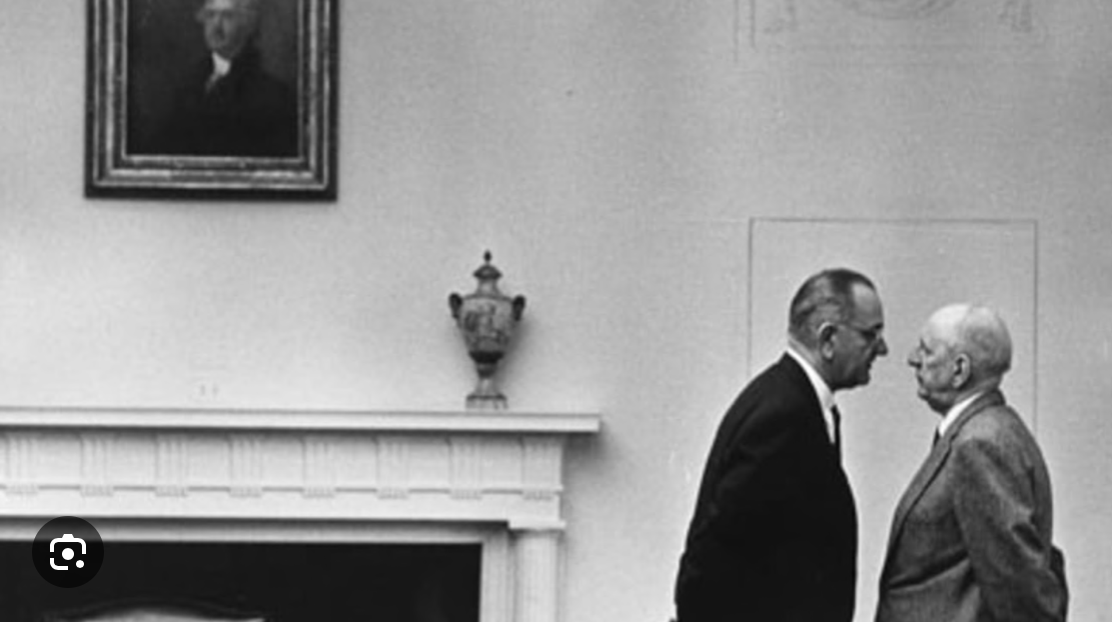

U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson was known as an aggressive leader, and one might use the phrase “in your face” to describe his style. That is not just a metaphor: one of his habits was to literally stand “in someone’s grill” — closer than normal distance rules would allow . In this photo he ’s talking to Senator Richard Russell Jr.

Standing with your nose two inches away from a romantic partner may be an expression of love, but if the person is a political opponent, that stance means something else entirely. Johnson knew this, and used it as an intimidation tool and a way to get Russell’s undivided attention.

You can try this technique with a rival, but be prepared for it to backfire . This is an illustration of Judee Burgoon’s Expectancy Violation Theory, which states that violations of nonverbal rules like this can lead to either dramatically good or dramatically bad outcomes, depending on how the people perceive each other.

You can use rule violations not only to intimidate people but to excite them . Some attractive servers in restaurants have figured out, for instance, that they can not only get away with touching customers on the arm or whispering rather intimately in their ear, but that they get bigger tips this way. If you overestimate your attractiveness, on the other hand, it’s a quick way to get yourself fired.

With those cautions in mind, let’s explore the ways in which you can communicate without words.

- Knapp, M.L., Hall, J.A., & Horgan, T.G. (2021). Nonverbal communication in human interaction (9th edition). Kendall Hunt Publishing. ↵

- Charney, E.J. (1966). Postural configurations in psychotherapy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 28, 305-315, ↵

- Bavelas, J.B., Black, A., Lemery, C.R., & Mullett, J. (1986). “I show how you feel”: Motor mimicry as a communicative act. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 322-329. ↵

- Hall, Edward T. (October 1963). . American Anthropologist , 65(5): 1003–1026. doi:10.1525/aa.1963.65.5.02a00020 ↵

- Stewart, R. (2006). The Places in between. Harcourt. ↵