Chapter 5: Audiences

5.4 Types of Audiences

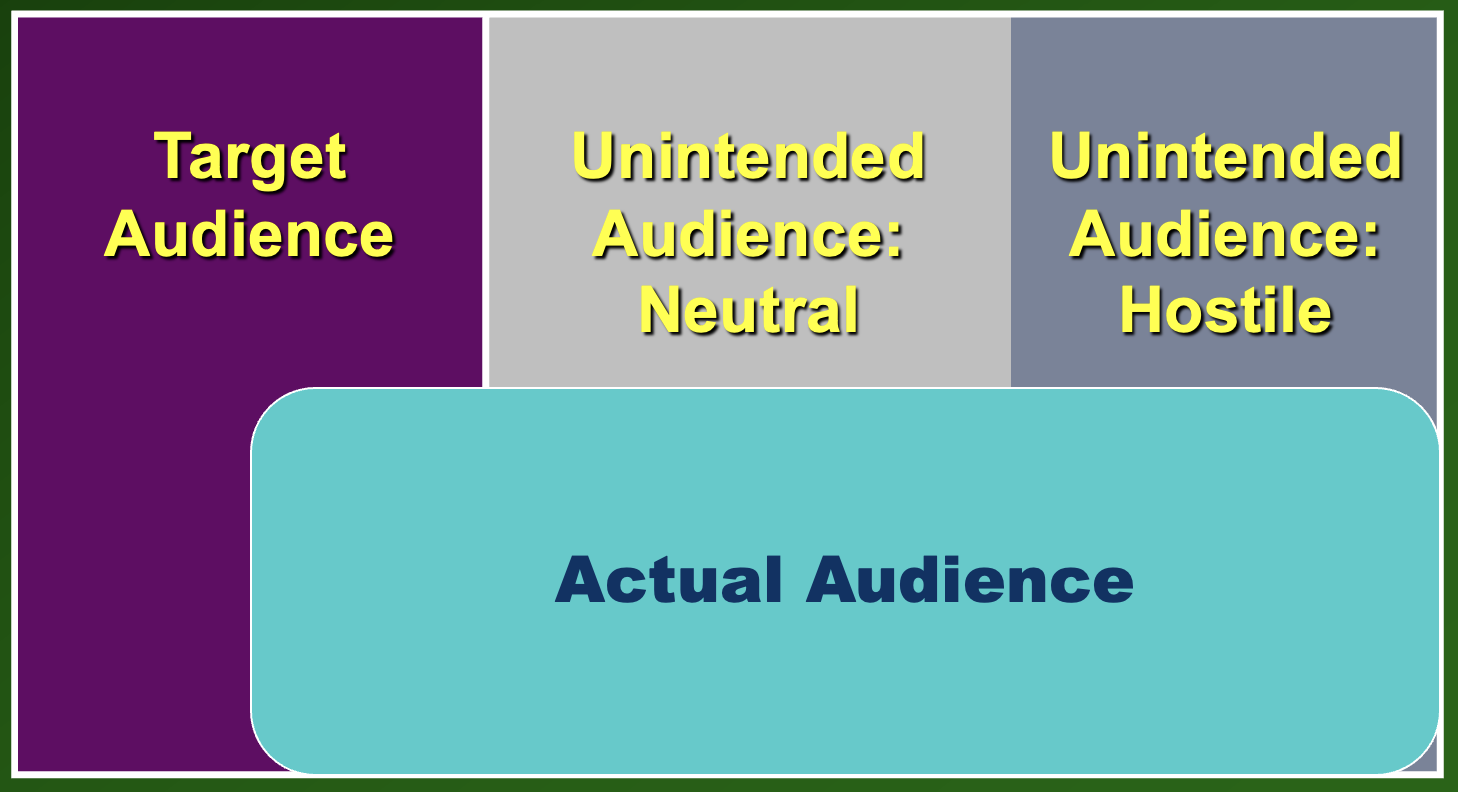

In addition to target audiences, it may be useful to think about other audience categories. For example, when the president gives a State of the Union speech, the people in the Senate chamber are not the only ones listening; the speech will be broadcast to voters and nonvoters, donors, political rivals, and international allies and enemies. While a speaker could get paralyzed worrying about who might be listening and what could happen as a result, it is still wise to think of audiences in terms of segments. Here is one model:

The target audience, as discussed, is the group of people the speaker wants to reach. Sometimes the speaker, or the source of the message, uses a two-step model to reach the ultimate target, starting with one audience who can’t enact the behavior on their own and assuming that they will put pressure on the second audience (SEE BOX 5.4 BELOW). The source gets to choose the target, so this category is under their full control. If they want to make a movie that is intended for fans of classic dolls who also love war movies, why not?

The actual audience is the set of people who hear or see the message, whether or not the speaker wants them to. This audience is automatically determined just by the fact of who is exposed to the message, but it is heavily affected by the message’s location, channel, and timing.

Unintended audiences are the members of the actual audience who are outside the target audience — people the speaker did not target. The nature of broadcasting and advertising means that there will always be people in this category. It is useful to further subdivide this segment into the neutral unintended audience and the hostile unintended audience. If you’re watching television and see a political ad for someone running for governor of a neighboring state, you can easily recognize that the message isn’t intended for you (you can’t vote for them anyway), but you may not have any strong feelings about that. But if you are the candidate’s political rival, you will pay careful attention to everything in the ad, and if you find anything you think would help your side and hurt theirs, you’ll definitely use it, putting you in the hostile category. You’re still part of the unintended audience, because the original candidate would prefer that rivals not scrutinize their messages.

While some politicians will do whatever they can to make sure there is no unintended audience and that everyone in the room is on their side, the political landscape is littered with people who found out the hard way that this is easier said than done. In 2012, presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s campaign was damaged by a comment he made at a $50,000-per-plate fundraiser. The comment may not have bothered any of the donors present, but it offended a bartender who filmed it and leaked the video.

Unintended audiences can also be created when a secure website is breached by hackers, or an insider shares the password. And there’s the “hot mic” situation, where a public figure says something intended to be heard only by those sitting close to them, and is unaware that a nearby microphone is recording everything.

It’s worth remembering how easily a message can reach an unintended audience. Many employees who work in high-stress jobs find relief in sending humorous messages to each other, making fun of customers or clients. All it takes is one co-worker clicking the “forward” button, and you’re fired. Likewise, there are innumerable examples of job applicants who survive a rigorous interview process and are close to receiving a job offer, only to have the company check out their social media postings (especially if the applicant wrongly assumed that the employer wouldn’t be able to see those messages). Some people create multiple social media profiles — some visible to the public, some that only close friends know about — to avoid these dangers, but juggling too many identities can itself be risky.

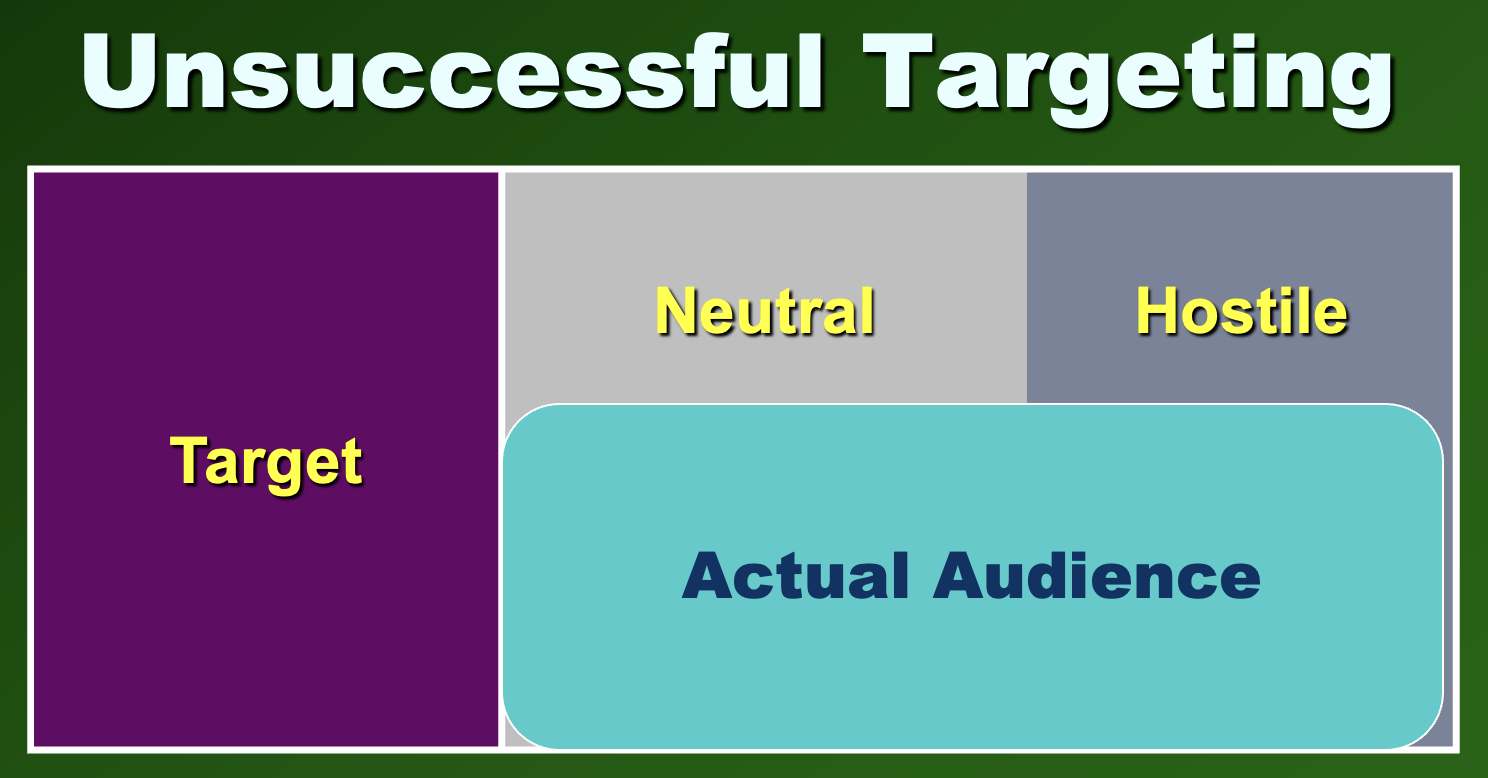

Depicting this model visually illustrates several ways in which communication can go wrong. If the target audience and the actual audience don’t overlap at all, the source is using the wrong channel or picking the wrong time and place to reach the target. In this case, it’s time for some creative rethinking about how to reach the target audience.

This also raises the question of width: how big are these audience segments? It depends on the situation, of course, but here are two interesting scenarios:

Narrow target, large unintended neutral audience. A common example is a television ad for a medication that treats a rare disease such as tardive dyskinesia (I don’t know anyone with that condition, but I’ve seen hundreds of ads for treatments). Although targeted advertising can be efficient, non-targeted advertising is the norm in many contexts. As department store mogul John Wanamaker is credited with saying over 100 years ago, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.”

Extremely narrow target, large hostile audience. Think of “spam” emails or “robocall” phone messages that annoy everyone. Have you ever wondered who actually falls for those messages and, if the answer is “no one,” why do spammers keep sending them? The answer is not quite “no one”: a 2008 study of spam messages revealed that while only 1 in 12,500,000 emails gets a response, that one person makes the work economically worthwhile for the spammers. In one month, 350 million emails led to only 28 sales, but those sales resulted in $7,000 in profits per day. And spammers don’t care if the rest of the world hates them.

One other noteworthy audience category is the imagined audience, which plays a role when a source needs to get themselves in the right psychological framework to deliver an effective message, but there is no real audience in front of them. For thousands of years, theater actors and musicians have gained energy and feedback from a live audience, but with the advent of recording and broadcasting technology, it became possible for actors, radio hosts, and musicians to perform without any audience in front of them. Now, even highly successful film actors say they prefer performing on stage because of that interaction, and musicians who play in large stadiums get nostalgic for the nightclub days when they could see their audience’s faces. Talk shows feature live audiences because it puts the hosts at ease and enlivens the conversation, even though the much bigger home audience is never seen. When shows stopped having a live audience during the pandemic, comedians had to get used to the daunting sound of silence after their jokes, and professors accustomed to in-person lectures learned how to record them in an empty office. Even after the lockdown ended, technology and economics have meant that many people once able to react to other live humans now have to rely on their imagination. (Think of being an actor in a science fiction film, and having to “react” to a tennis ball that will be replaced later with a computer-generated scary monster).

All of these scenarios illustrate the principle that delivering an effective message often requires the speaker to have a strong imagination. It helps if that imagination is built on a backlog of real audience reactions, but people with little experience in how people will respond to their message still have to conjure someone to talk to — a person, rather than a blank wall or an unblinking camera.

If you’re in this situation, it may help to imagine just one person you know, whether they are physically present or not, and give your speech to that person. The 2010 film The King’s Speech provides a great example. King George VI knows that, despite his severe stutter, he will have to address his nation, and his speech therapist, Lionel Logue, has done everything he can to prepare him for this terrifying experience. How does a king with a stutter address an audience of tens of millions of people? Alone in a room with a microphone and his friend Lionel, who instructs the King to speak just to him. On the other hand, if it helps to imagine a huge and adoring crowd, put that image in the front of your mind instead. Getting comfortable talking to an audience that’s not physically present is a skill that is likely to pay off many times in your life.

BOX 5.4: TWO-STEP TARGETING

Logically, TV ads for prescription drugs don’t make any sense. No matter how much a patient may want a prescription drug, they can’t obtain it without going to a doctor, who will decide what the patient should take. Knowing this, for most of the 20th century drug companies didn’t bother advertising directly to patients: they targeted doctors, visiting their offices, attending medical conventions, and putting notices in medical journals.

So why did they change their mind in the 21st century and start pouring billions of dollars into advertising straight to the consumer? Because they know how effective it is when a patient demands a certain medicine from their doctor.[1] And why would doctors, with far more medical training than their patients, give in to these requests? One clue can be found in the stilted language you often hear in those commercials: if you’ve ever heard a normal person describe their plaque psoriasis as “moderate to severe,” let me know, but I’m willing to bet that when the doctor looks it up in the official drug guidelines, the language matches precisely. In other words, the ads are training patients to use the language that will be most effective in getting them the drug.

The 2009 documentary The Corporation delves into two-step targeting when it comes to children, and the discovery that getting children to nag their parents is extremely effective. In the film, Lucy Hughes of Initiative Media reports on research showing that “anywhere from 20% to 40% of purchases would not have occurred unless the child had nagged their parents.” She acknowledges that parents don’t like it when this happens (“We do have to break through this barrier where they say they don’t like it when their kids nag”), but dodges the question of whether this is ethical communication. Perhaps the guidelines in Chapter 3 would help her answer that question.

- In 2015, the AMA considered calling for a ban on this practice, but never pursued it. ↵