Chapter 6: Persuasion

6.4 The Yale 5-Step Model

Identifying the role of intellect, emotions, and circumstances, however, doesn’t quite tell you what you need to do in order to persuade. To get a more concrete idea of the steps needed to persuade someone, let’s go back to World War II, a time when people felt an urgent need to better understand the persuasion process.

The Allies (Great Britain, the U.S., and other countries) recognized that if they were going to win the war, it wasn’t enough to have planes and tanks and soldiers. Winning would also require beating Hitler at his specialty: propaganda. Hitler had been so successful at persuading a previously reasonable country to do something insane — systematically murder millions of civilians — that the Allies were strongly motivated to learn what Hitler knew about persuading the masses. This led to the recruitment of three psychologists from Yale University (Carl Hovland, Irving Janis, and Harold Kelley) to learn as much about the persuasion process as possible. Out of this came a model of persuasion that has gone by different names, including the “Single Shot” studies (since they were focused on how to persuade an audience if you only had one opportunity to do so) and the Yale Attitude Change Model.[1]

The psychologists originally identified three steps in response to hearing a persuasive message: attention, comprehension, and acceptance. Later, they recognized the importance of two additional steps: retention and action. Retention is another word for “remembering,” which matters when there’s a lag between hearing the message and acting on it. They must also be driven to act: to go to the store to buy something, get off the couch and go vote, or convince someone else to join their cause. Based on those additions, Charles Larson reframed Hovland, Janis, and Kelley’s model as a five-step process:[2]

- Attention: the audience must notice the message

- Comprehension: the audience must understand the message

- Acceptance: the audience must accept the message

- Retention: the audience must remember the message

- Action: the audience must act on the message

Are all five steps necessary? You could argue that it’s possible to persuade people even if they don’t understand your message (comprehension), and that not all persuasion requires action (such as PR campaigns designed just to change minds or reinforce existing attitudes), but in most circumstances this is a good formula for tracking what you need to do in order to persuade someone.

These steps may sound simple and easy, but they’re not: all are easier said than done, and there are whole fields of research devoted to understanding how each of these separate processes work.

Let’s examine them in detail by looking at an example: Jonah and his friends have formed a band, Kangazoo, whose unique angle is hip hop music performed on traditional Jewish klezmer instruments (violins, clarinets, woodwinds, cymbals). Jonah’s broad goal is to achieve popularity and success, but his immediate goal is to persuade people to show up to a Kangazoo nightclub gig in three weeks. What does Jonah need to think through?

Attention. When those Yale psychologists first devised their model in 1953, the fight for attention was nothing like it is today. But while that fight has grown exponentially more intense, the issue remains the same: attention is a finite resource. The individual audience member only has so much attention, and turning it toward one thing inevitably means turning it away from something else. Yes, some people pride themselves on being multi-taskers, but neurological research proves that this is a myth: you just can’t fully devote your attention to more than one thing at a time. Combine that with the erosion of gatekeepers and the arrival of new opportunities for everyone to enter the fray (SEE Chapter 18), and more and more people are fighting for the attention of potential audience members.

In the case of Jonah and his band members, the good news is that they don’t have to get signed by a record label, as they would have had to do decades earlier. They can create their own website, set up an Instagram account, post videos of a few songs on YouTube and audio versions of the same songs on Soundcloud, and set up a Tik Tok page. Now the first challenge: how to draw attention to those social media outlets. They can hire someone to help with search engine optimization, but they’re discouraged to hear that their YouTube channel is one of 38 million active channels, and that their music videos are competing against the 450,000,000 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every single hour.

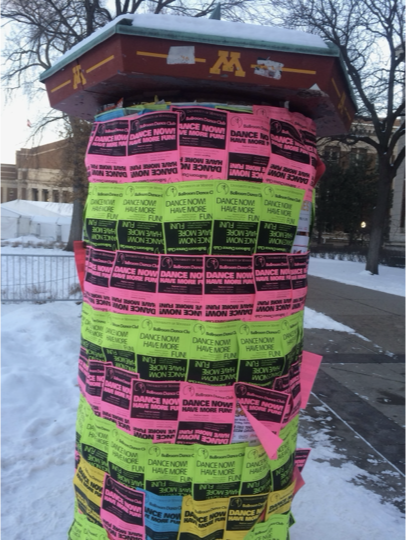

Instead of worrying about the global potential, Jonah decides to focus on the local audience, and lets all of his friends know about the upcoming gig. The trouble is, he doesn’t have that many friends, and some are going out of town to a music festival in Tennessee that weekend. Since he attends a large university, at least there are opportunities like on-campus kiosks, and Jonah makes up a lot of brightly colored posters and plaster the kiosks with them:

This succeeds in getting the attention of a few dozen students who walk past, but by the end of the day another band has put posters on top of Jonah’s. That’s the other thing about attention: you may come up with techniques to break through the clutter and get the attention of a wider audience, but other competitors can use the same techniques, and then you’re all back to square one. Meanwhile, the potential audience is tired of being bombarded, and gets steadily better at tuning out all the constant demands for their attention.

Comprehension. This isn’t as big a challenge for Kangazoo as it would be for a lawyer presenting a complex case to a jury, or a scientist attempting to explain to politicians why they need to pass climate legislation. In those situations, the challenge is how to simplify the message without distorting it or “dumbing it down” to the point that it’s inaccurate. As discussed in Chapter 4, audiences that can’t understand what you’re saying tend to stop listening, so comprehension and attention are tied together. Politicians have learned the importance of simple messaging, but that often results in slogans that are so short and simple that they don’t really say anything (the same happens with corporate slogans like American Eagle Outfitters’ “Live Your Life” or UnderArmour’s “I Will”).

In Jonah’s case, he ponders whether it’s worth the trouble to try to explain what klezmer music is and how a klezmer/hiphop combination would sound, and worries that people will think the name Kangazoo sounds like a children’s band or one that plays aboriginal Australian music, but in the end he decides that if people really want to understand, they’ll just have to show up to the gig.

Acceptance. This is in some ways the heart of the matter — if the audience has accepted the message, doesn’t that mean that the persuasion was successful? It leaves open the question of why an audience would accept or reject a message. Is it because of the logic of the message [Chapter 7], emotional appeals [Chapter 8], the credibility of the speaker [Chapter 9], skillful language use [Chapter 10], appealing stories [Chapter 11], artful use of nonverbals [Chapter 12], or effective use of media [Chapter 19]?

At least Jonah knows enough to put careful thought into his advertising: wording, imagery, design, and music. Still, he worries about the attention step so much that he is tempted to start using extreme attention-getting measures that might undermine the acceptance step. He notices, for example, that some musicians draw traffic to their videos by wearing provocative clothes. He can’t think of anything he could wear that would have that effect, but even if he was sexy enough to pull it off, he worries that people wouldn’t take his music seriously as a result. He recalls too many examples of hopeful social media stars who would seemingly do anything for attention: licking toilets, putting gorilla glue in your hair, or animal cruelty. While all of those people did succeed in “going viral” and getting short-term attention, it is unlikely that their actions led to long-term success as a social media figure. In other words, it is worth thinking hard about how to gain attention without sacrificing acceptance in the process.

The clash between attention and acceptance bleeds into many other domains as well. Politicians know that they won’t get quoted for saying calm, reasonable things, so some make deliberately ridiculous statements just to get in the news every day. Car dealerships run commercials full of shouting and wacky promotions, online ads feature strobe lights and intrusive music that you can’t turn off, promotional emails tout “amazing” deals that aren’t amazing, and “clickbait” websites make sensational promises that are rarely fulfilled (“Stunning pictures of celebrities without makeup; you will gasp at #7”). What all of these have in common is that the word “gimmick” applies, and gimmicks are not a good long-term strategy. Once people catch on to the gimmick and realize that it wasn’t worth the excitement, they learn not to pay attention.

As another example, protesters know that a protest that doesn’t receive any media coverage is a waste of time, so they have to make choices about the best way to get that attention: Wear silly costumes? Take off your clothes? Disrupt the lives of people going to work? Set something on fire? All of these techniques run the risk of turning people against you, but the protesters may decide that that’s better than being ignored.

The challenge of figuring out how to gain attention without sacrificing acceptance has no easy answers, but is a conundrum that all persuaders should think about carefully.

Retention. Many scientists have devoted their careers to understanding human memory and how it works. A persuasive message doesn’t do any good if it is immediately forgotten, and advertisers frequently worry that consumers will remember their ad, but not what brand it’s for. Pepsi may invest a lot of time and energy into creating an original and memorable commercial, for example, but despite their best efforts, some people will remember it as a Coke ad instead. This is why so many commercials devote so much energy to one simple goal — getting people to remember the name of the product — that they barely say anything else. They use all manner of memory-assisting techniques, from catchy “jingle” songs to celebrity cameos to humor to rhyming slogans, to help the viewer remember the brand name (or the phone number, or the location of the store).

Jonah knows that part of his task will be to get people to put the gig on their calendars. If they show up at the wrong time or place, it won’t do his band any good. He also reminds himself to repeat the band name frequently during the gig itself; he’s seen too many bands that played for an hour, but after the hour was over he still didn’t know what they were called.

Action. Jonah’s biggest challenge is to get people to leave the comfort of their homes and come to the show. As Woody Allen put it, “90% of success in life is just showing up”. Many people don’t show up to things, despite their good intentions. Turnout rates in American national elections have hovered between 50% and 65% for nearly a century, which means that at least a third of the American population forms opinions about who they would like as their next president but still doesn’t cast a vote. No wonder politicians put so much effort into “mobilizing the base” and figuring out what gets people to show up at the polls.

Some people think that raising awareness is itself enough to solve problems, which in this model is equivalent to saying that attention (step 1) is action (step 5). Although it is certainly true that awareness is essential, thinking that it’s the only thing necessary to solve a problem seems like pure optimism to me.

Take, for example, a 30-minute video by Jason Russell entitled Kony 2012, about a war criminal named Joseph Kony who was using child soldiers to fight his cause in Uganda. The stated purpose of the video was to increase awareness of Kony’s atrocities and have him arrested by the end of 2012. It certainly did raise awareness: it received over 100 million views on YouTube, and was called “the most viral video of all time” by Time magazine in 2013. What were those millions of viewers called on to do? The main action called for was to share the video with others, which many people did.

Was Kony arrested by the end of 2012? No, he wasn’t, and by 2017 both the U.S. and Uganda had given up the hunt for him; as of this writing, he is still at large. The film has since been labeled as a classic example of “slacktivism,” a form of protest in which supporters of a cause do low-effort things such as liking or sharing a video instead of anything effortful or tangible.

What can Jonah do to get people to show up at the gig? He’s read about techniques used by political volunteers to get voters to show up at the polls — sending reminders shortly before the election, asking explicitly for commitments, and removing “path” barriers by providing transportation — and wonders if those would work for his audience. In the end, it all seems like a lot of work, and Jonah longs for the day when he and his band members don’t have to do any of that, and can just concentrate on playing the music. But if you have a similar persuasive goal (getting social media followers, protesting about a political crisis, or getting a university official to waive a requirement), thinking about attention, comprehension, acceptance, retention and action may help.