Chapter 7: Logic & Reasoning

7.2 The Parts of an Argument

Children tend to have arguments that follow a very simple structure: one child says “Hockey is the best sport,” and another responds, “No it isn’t.” This might go back and forth for a few rounds, but neither is convinced by the other’s arguments. A famous Monty Python sketch from 1972 has a similar structure, with a customer of the “Argument Clinic” (played by Michael Palin) asking the Arguer (John Cleese) if he’s in the right room and the Arguer responding “I told you once.” This is followed by a long string of “No you didn’t” / “Yes I did!” until the customer complains that it isn’t even an argument, it’s just contradiction. When the customer explains “Argument is an intellectual process; contradiction is just the automatic gainsaying of anything the other person says,” the Arguer responds “No it isn’t” and the pointless volleys resume.

The customer in this sketch was hoping for the kind of conversation in which ideas are promoted and explored, an opponent offers counterarguments, and perhaps a resolution is reached. Since conversations are inherently complex, this isn’t the meaning of “argument” I’ll examine in this chapter. Here, “argument” will mean reasoning put forward by one person. I’ll look only at the content and logic of statements (the “M” in the Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver model), not the conversational process, with all its twists and turns.

Claim and Support

Does “hockey is the best sport” qualify as an argument? No, because it’s missing a necessary component. By itself, it’s just a claim: an assertion that the speaker wants to prove. To meet the minimum standard of an argument, it also has to have some form of support: “Hockey is the best sport because it’s so fast-paced.” What’s in that “because clause” can have many names, including:

- Evidence

- Proof

- Reasons

- Grounds

- Backing

- Support

Why is support so important? As Hitchens’s razor states, “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”[1] Picture a field with a sign in front that reads “No trespassing.” Contrast it with a sign that reads “No trespassing: Field is infested with scorpions.” Better yet, envision scorpion tails in the dirt behind the sign. It’s usually the evidence that convinces people, not the claim.

The distinction between claim and evidence, however, isn’t always so clear. In the hockey argument, “it’s so fast-paced” is also a claim that requires its own support. The same phrase can thus be either a claim or a form of evidence, depending on what function it’s performing. In other words, the difference between claim and evidence is one of function, not of form or content.

There are also differences between the terms in that second component: “evidence” implies something tangible and verifiable, perhaps represented as numbers, but “reasons” imply something that just “makes sense.” The child’s question “Do people live on Pluto?” can be answered using scientific evidence (e.g., not unless they can breathe methane and enjoy a cool -387 degrees Fahrenheit). But when she goes on to ask “If there are people who live there, then they won’t exist,” you can answer her without scientific evidence: the IAU didn’t destroy Pluto, but just renamed it, so no Plutoans were harmed. Making an argument based on reason, in other words, is different from finding evidence — although you could call both of them “support.”

Warrant

To make a statement an argument, what other components are needed besides a claim and support? For the argument to work, those two elements need to be connected. It doesn’t work, for example, to say “Hockey is the best sport. Oranges are in season right now.” Unless you don’t want to get asked “What on earth are you talking about?,” you must have a thread between the two sentences — even if that thread is invisible.

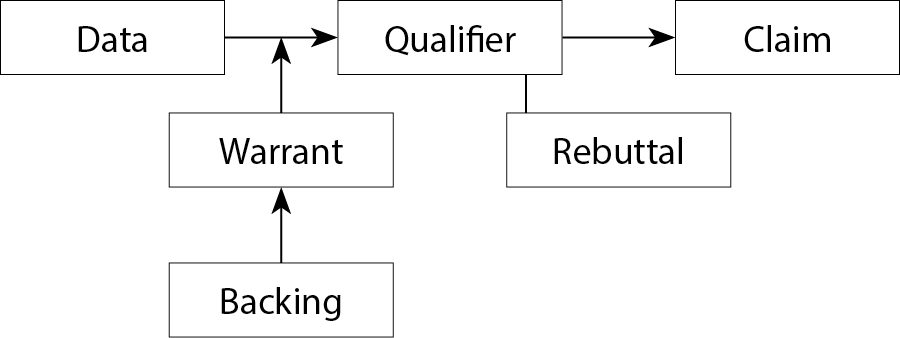

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin calls this thread the “warrant.” It can be described in various ways, but they all involve connecting the support (which he calls the “grounds”) to the claim. The warrant is what authorizes the inferential leap from the grounds to the claim — the underlying assumptions that allow you to say “these grounds support the claim.” Another way to put it is that warrants are the assumptions or values that drive the reasoning.

In the hockey example, the assumption is that “fast-paced” is a good quality in a sport. Not everyone will agree, but for the people who do, the argument “Hockey is a great sport because it’s fast-paced” makes sense. This taps into a concept that Toulmin stressed: effective arguments are based on assumptions that the audience accepts.

One tricky thing about warrants is that they’re almost never stated out loud, so it takes some digging to find them. Imagine a home builder who wants to have the modern amenities: water, electricity, sewer, perhaps natural gas. Unless they want to live completely “off the grid,” they will need to get those utilities from the neighboring community (the city), and most of the connections will be invisible because they are underground. Likewise, the connection between the claim and the grounds is also usually invisible, but can be inferred.[2] It doesn’t take a lot of detective work to figure out that “fast-paced is a good quality for a sport” is part of the hockey argument, even though it wasn’t stated out loud.

Why not always state the warrant out loud? It’s unnecessary, and slows down the conversation. The Ancient Greeks used the word “syllogism” for a classic three-part argument where everything is stated explicitly: “Being fast-paced is a good quality in a sport. Hockey is a fast-paced sport. Therefore hockey is a good sport.” But aside from Socrates, who talks that way?

Those Ancient Greeks recognized that arguments in which not everything is stated directly are actually more effective than syllogisms, and they had a word for these as well: “enthymemes” (EN-thu-meems). Why are arguments with unstated parts better than fully explicit ones? It’s not just about saving time, it’s about who fills in the missing parts. If it’s the audience, they are less likely to question the argument. This is why advertisers are so fond of vague slogans. Since 1944, Hallmark greeting cards have used the slogan, “When you care enough to send the very best… Hallmark.” If they just said “Hallmark is the very best,” it would be greeted with skepticism, objections, and possibly lawsuits, so they don’t spell out this assumption; instead, it’s in the three little dots (known as “ellipsis,” another Greek word). Three little dots won’t get you in trouble, but they are the heart of the argument.

Because warrants are usually invisible, learning to identify them is a key skill in being able to analyze or formulate arguments. You may have heard the expression “It takes 43 muscles to frown and 17 muscles to smile.” Here, even the claim (that you should smile more often than you frown) is unstated, but there are many other layers of unstated warrants buried underneath:

- The assumption that both smiles and frowns are singular expressions that always take exactly the same number of muscles. Aren’t there many different kinds of smiles and frowns, and don’t they all use different muscles?

- The assumption that using muscles is a bad thing that you should avoid if possible.

- The assumption that your choice of facial expression should be based primarily on the number of muscles used, not on how you feel.

- Finally, logic dictates that if it’s better to smile than to frown because you use fewer muscles, then having no expression at all is even better, and you should spend as much time as possible with a completely blank face.

If you think any of these assumptions is shaky, the argument falls apart. But instead, people just treat this as a cute expression and embroider it on pillows. (By the way, the numbers are wrong: there are only 43 muscles in the entire human face, and no expression uses all of them. Also, depending on the type of smile or frown, smiles often use more muscles than frowns.)

Toulmin vs. LOBs

Warrants, along with claims and grounds, form key parts of a model of argumentation known as the Toulmin Model. They are not the only components, however. Because audiences and opponents can often think of counterarguments against your claim, you are in a stronger position if you anticipate those arguments. In some circumstances, you have an opponent who will jump in with those responses as soon as you’ve made your case; in others, you have an audience rather than an opponent, and they will think of the responses on their own.

Consider this claim: “You should give up your car, and ride a bicycle everywhere instead.” To make it an argument, you can add a list of reasons:

- Bicycling will save you money on gasoline, parking, and repairs

- You will not contribute to greenhouse gas emissions

- You will get exercise and fresh air

- You can go places that cars can’t go

- You are likely to see more wildlife and smell more pleasant aromas

- You are more likely to have conversations with other bikers

Is this a strong argument? Actually, it’s a weak one — one you could call a “LOB,” short for a “List of Benefits”: a straightforward list of things that support your main point. Why is that weak? The answer lies in the other meaning of “lob”: it’s a tennis term that refers to a shot with a high arc.

If you’re a beginning tennis player, you may be proud of hitting a ball so high in the air, but you’ll quickly discover why that’s a bad thing: it is far too easy for the opponent to hit it right back. Getting the ball over the net doesn’t accomplish much if it’s back in your court in two seconds.

While you were reading the list of benefits of riding your bicycle everywhere, what were you thinking? Perhaps questions such as:

- Yeah, but what about bad weather?

- Yeah, but doesn’t it take longer to get there?

- Yeah, but don’t you get tired and sweaty?

- Yeah, but isn’t it dangerous?

- Yeah, but what about passengers?

- Yeah, but what if you need to transport things?

If you didn’t anticipate any of those “yeah, but” counterarguments, you’ll lose the debate quickly. In fact, it would be most effective to head off these points in advance instead of waiting for your opponent to bring them up or an audience member to wonder about them. This is why Toulmin says a strong argument requires a fourth element: the rebuttal (the response to counterarguments). I’ll discuss techniques for how to rebut[3] an argument below.

Another option is to add qualifiers to your claim. These are adjectives and adverbs, often just small words that may go unnoticed but make a big difference. Their purpose is to back off from the certainty of what you’re saying, and qualify your claim. An unqualified claim is one that you’re asserting is 100% true in all possible circumstances; a qualified claim, in contrast, acknowledges exceptions and uncertainty through phrases such as “may be,” “possibly,” “in these situations,” or “often.”

You may think that adding qualifiers makes your argument weaker, not stronger, but the opposite is true. If you assert something as true without qualifications, it doesn’t take much to prove the claim wrong. Take the unqualified claim “Everyone hates algebra.” What would it take to disprove that claim? Just one math lover. Now back off from the certainty and see what happens: “Most Americans dislike algebra.” You toned the emotion down from “hate” to “dislike,” you narrowed the geographic scope from the entire planet to one country, and, most importantly, you added the small qualifier “most.” Finding one math lover doesn’t disprove the claim; indeed, finding millions of math lovers still doesn’t disprove it. If you tone it down even further to “many Americans,” even finding 300,000,000 algebra fans won’t make it a false claim.

Qualifiers make your job easier by giving you less to prove, which in turn makes it easier for a skeptical audience to accept your claim. In the hockey argument, do you need to prove that it is the greatest sport in the world, or is it enough to show that it’s “a great sport”? If you take the second approach, your job will be much easier. In the “give up your car” argument, notice how many problems you’ll solve if you add qualifiers: “If you’re not traveling too far and the weather is good.”

Finally, sometimes a warrant itself needs some support. Toulmin called the elements that support the warrant the backing. The distinction between the grounds (that support the claim) and the backing (that support the warrant) may be a subtle one, and if the audience already accepts the warrants, backing isn’t necessary. In other situations, however, backing is needed to create a strong argument. Is it worth taking the time, for example, to establish that “fast-paced” is a good quality in a sport? If so, think of other examples of fast-paced sports to support that warrant.

What can you do with a diagram like this? If you want to analyze other people’s arguments in depth, it’s a good tool to guide you. If you want to make your own argument, it’s a reminder of the pieces that can help you strengthen it.

BOX 7.2: BY YOUR LOGIC, I HAVE TO TAKE MY SHIRT OFF

One reason it’s valuable to be able to identify warrants is because sometimes you can beat your opponent over the head with their own warrant. This was the case with a woman who posted on a biking forum in 2007 under the name ReachHigher. She biked to a Walmart four miles from home. When she got there, she found that there were no bike racks, so she brought her bike into the store. After being told by a greeter that she wasn’t allowed to do this, she got into an argument about it with the store manager. The manager told her she couldn’t bring the bike in because they sold bikes in the store — even though the shopper pointed out that her bike looked nothing like the ones they sold and was clearly not new. In the blogger’s words:

I was starting to get really frustrated since I had ridden all the way there seemingly for no reason, so I asked her if they also sold shirts in the store. She said yes so I took off my jersey and said “Well then I’d better not bring this in either.” She got kind of flustered and said that it was a different situation but couldn’t explain why. So I said that if they also sold shorts in the store that I’d better not wear those in either and I took off my shorts. Same goes for the shoes and sunglasses. Now I’m standing there in my spandex and a sports bra and I ask her if I can leave my things behind the customer service counter where they will be safe until I finish making my purchases and she said that I couldn’t come into the store without shoes on, to which I responded “but I certainly can’t wear shoes into the store because you sell those here and someone might think I’ve stolen them.”

The biker ends the tale with “I was pretty tempted to take off the spandex too but I wasn’t sure what constitutes indecent exposure in Virginia so I figured I’d err on the side of caution.” Whether she won the argument depends on your point of view (she turned around and left the store), but she certainly succeeded in building an argument to which the manager couldn’t think of a response. Her best weapon was taking the manager’s warrant, “You can’t bring things into a store that the store sells,” and showing how untenable that position was.