Chapter 6: Persuasion

6.5 Dual Processing Models

The last model commonly used in Persuasion courses is not a single model, but rather three closely related ones: Petty and Caccioppo’s Elaboration Likelihood Model, Chaiken’s Heuristic-Systematic Model, and Kahneman’s System 1 vs. System 2 Thinking Model. The scholars themselves would explain how these models differ, but to many audiences, they all seem to drive at the same idea: when a listener hears or sees a persuasive pitch, they can respond in two distinctly different ways — sometimes giving the pitch a lot of careful thought, and other times responding in very simple ways or making quick decisions.

|

Authors |

Simple |

Complex |

|

Petty & Caccioppo |

Peripheral processing route |

Central processing route |

|

Chaiken |

Heuristic: Take shortcuts, rely on simple logic |

Systematic: think things through, gather evidence |

|

Kahneman |

System 1: fast, subconscious, emotional, intuitive |

System 2: slow, effortful, logical, conscious |

Petty and Cacciopo’s model is called the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) because one mode involves the listener elaborating on the model, referred to as “central processing” (picture the cerebral cortex responding to the message by kicking into gear and processing the message thoroughly). They call the other mode “peripheral processing” because the listener’s decisions are based on less important factors, such as how something looks.

Chaiken’s Heuristic-Systematic Model of Information Processing uses similar terms, calling the first mode systematic processing of the message, while the alternative is to rely on shortcuts (known as “heuristics” or simple rules of thumb) that bypass the need for deep thinking.

Daniel Kahneman’s model was introduced in a 2011 book called Thinking Fast And Slow, which emphasizes the relative speed of these two modes of thought: System 1 is fast, instinctive, and emotional; System 2 is deliberate, slow, and logic-driven.

In the table above, the elements in the “Complex” column are explored in Chapter 7, the chapter about reasoning and logic; here we’ll focus on elements in the “Simple” column.

In the 2007 film No Country For Old Men, Llewelyn Moss (played by Josh Brolin) needs to cross the border from Mexico into the U.S., and the border guard has reason to be suspicious: Llewelyn has no identification and is wearing only a hospital gown. The guard makes it clear that he alone has the decision-making power, and his tough talk suggests that he is going to base his decision on careful thought: “How do I decide [who enters the country]? I ask questions, and if I get sensible answers, then they get to go to America, and if I don’t get sensible answers, they don’t.”

If the guard knew the reality of the situation — that Llewelyn has stolen a suitcase full of drug money, and is being chased by a hit man — he would not let him in, so the guard would presumably want to know a lot about his situation, citizenship status, and why he doesn’t have identification. But after asking just one question (“How did you come to be out here with no clothes?”), he switches to a different line of questioning: “Are you in the [military] service?” Llewelyn reports that he served in Vietnam in the 12th Infantry Battalion, and the guard is satisfied and lets him in. What level of thinking is that?

The guard’s decision seems to be primarily based on one thing: Llewelyn is a veteran, so he must be a law-abiding, honest citizen (he isn’t). The guard makes his decision in less than 30 seconds, which definitely qualifies as “thinking fast,” he is relying on a heuristic (military means honest), and he spends no time elaborating on the message he hears. Assessments about credibility [Chapter 9] are often made on the basis of appearances, associations, or assumptions — and shouldn’t be.

Heuristics / Peripheral Cues. People in peripheral processing mode employ “mindless reliance on nonessential cues.”[1] What counts as nonessential or mindless? For this discussion, we can narrow it down to three things:

- Simple associations

- Visual appearance

- “Following the herd” (sometimes called “social proof”: looking to other people as guides for behavior, and assuming that if a lot of people are doing it, it must be the right thing to do).

Beginning with simple associations, let’s think about Russian researcher Ivan Pavlov, and his famous experiment with dogs. He started with the observation that when dogs see food, they start to salivate — a natural (“unconditioned”) response to help them swallow the food. He also recognized that there is no natural reason why a dog should have a physiological reaction to a bell; it’s a sound that on its own means nothing to a dog. When Pavlov put food in front of his dogs, he also rang a bell, getting them to associate that sound with food. After doing this enough times to fix the association in each dog’s mind, he took the food away and the dogs salivated at the sound of the bell alone — an unnatural, “conditioned” response.

Two key points about this kind of association: it’s easy to form, and it doesn’t require any logical or natural basis for the association. A century later, this simple idea has become the basis of a large percentage of advertising. You may think the purpose of advertising is to tout the benefits of a product, but if you look closely at a lot of ads, you’ll see that they don’t actually say anything about the product: their whole purpose is simply to make an association between the product and a lifestyle or a feeling.

If you’re selling a perfume or cologne, for example, people might want to know how it smells, how much it costs, and perhaps how it’s made — but I dare you to find a perfume/cologne commercial that mentions any of those three factors. Instead, you’ll find countless commercials featuring very attractive people living cool lives, with the vague implication that if you buy that same scent, your life will become that cool as well. Similarly, this is why so many banks and financial institutions buy naming rights for sports stadiums: “When you think of your beloved team, think of our bank.”

In terms of visual cues, appearance may or may not mean that a computer is a good one, but Steve Jobs was insistent that Apple computers looked and felt cool, knowing that many people would buy those computers (and later, Apple phones) based on those factors. Appearance is especially important for websites: given the statistics about how much time people spend “sizing up” a website (an average of 52 seconds), it is vital that a home page look attractive. And salespeople know that “dressing for success” is important, shelling out for expensive cars and jewelry early in their career, when they can’t really afford it, because it conveys the message that they must be good at their job.

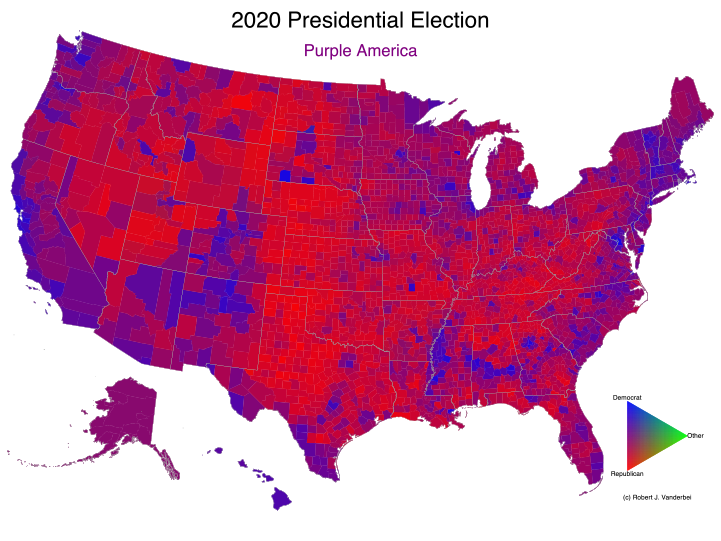

As for group factors, although many people see themselves as independent thinkers who aren’t influenced by their group, research proves that people imitate those around them much more than they realize.[2] Think about voting maps such as this one, which shows geographic voting patterns:

If people made up their minds individually about who to vote for, why would there be any geographic patterns at all? Or think of one specific form of political persuasion: yard signs. They rarely contain information beyond the candidate’s name, so how can they have much persuasive power? Even without any details, they do seem to perform two vital functions: they increase name recognition (contributing to the attention phase discussed earlier), and they tell people who their neighbors are going to vote for. Do people really look around and find out what the neighbors are doing before they make up their own minds? So it would seem.

If there are two distinct mental processes that people can use when they are exposed to a persuasive message, why go one way or the other? The choice seems to boil down to three main factors: motivation, ability, and personality.

Imagine a friend who launches into a lengthy argument about why Major League Baseball should institute a hard salary cap. If you care deeply about the topic, your motivation has probably already led you to spend a lot of time thinking about it, and you won’t be swayed to change your mind by simple arguments. But if you’re a casual baseball fan and your friend seems to be making even a small amount of sense, that will probably be enough to get you to agree with them. Is it worth it to you to look up a lot of articles, read them, and take the time to think them through? No; five minutes is about as much time as you want to spend on that topic.

Ability is another factor: if you have a good grasp of the economics of baseball and can track a long discussion about the relative merits of the Competitive Balance Tax vs. a hard salary cap, you’ll stay on it. But if you can’t follow what your friend is talking about, you’ll slip into peripheral processing mode and just think “My friend seems passionate about it, so they’re probably right.”

Finally, some people have the type of personality that is drawn to complex thought, and perk up their ears when someone says “Actually, it’s more complicated than that…”. (In psychology terms, they have a “high need for cognition”). Other people get a headache when things get too complicated, and are more comfortable looking at the world in black-and-white terms.

This mental processing takes place inside the mind of the receiver, of course, so the persuader doesn’t have ultimate control over how the audience responds to the message. However, you can easily recognize when the persuader is encouraging central processing (by posing thought-provoking questions, providing a lot of information, or giving the audience means to do further research, such as including hyperlinks to articles), and when they want the audience to be in peripheral processing mode instead (prioritizing imagery over words, relying on Pavlov-style associations, and keeping things very simple). Since central processing / systematic thinking means that the receiver ultimately makes up their own mind, and since it can take a long time, it’s easy to recognize why most advertisers prefer their audience to be in peripheral / heuristic mode. This is why perfume/cologne commercials don’t tell you anything about the product; it would put the audience in the wrong mindset.

If you are reading this book, that might mean that you have a high need for cognition, just like me (and most college teachers and students). And if you turn on the television and see a lot of commercials that are mindless and simplistic, instead of shaking your head and thinking “Why do they make ads so stupid?,” you can just recognize that you are not in the target audience. (See Chapter 5).

BOX 6.5: HOW TO SELL YOUR OLD CAR

If you haven’t read the chapter about ethical communication (Chapter 3), please do so now. Some persuasion techniques skirt the boundaries of ethical communication, or could be characterized as manipulation or gimmicks. That said, here are six tried-and-true persuasion techniques you could use if you want to sell your car:

Low-Balling: Start off with a low price, and once the customer has expressed interest, you can begin adding extra fees. If you’ve bought tickets to a sporting event or concert, you’ve seen this in action: “convenience fees” or “booking fees” or taxes that in some cases double the originally advertised price. Some people will cancel the sale, but people who have their heart set on getting that car will put up with the annoyance of the extra fees.

High-Balling: Curiously, you can also go the other way — ask for a sky-high initial price, but be willing to accept much less. The idea is that if you start off quoting an unreasonably high price and the customer refuses, you look reasonable by lowering the price (or the customer might feel guilty about saying no). The trick here is that you never expect to get that high price. If you live in a culture where haggling is common, you know all about this technique.

Sweetening the Deal: Give the customer something “free” in addition to the car: “I’ll throw in a free set of jumper cables and a food cooler.” I put “free” in quotes because you already factored that into the selling price, so it’s not really free — but to the buyer, it feels like a bonus. To do this well, timing is important: in the old infomercials, they would first convince you that the basic product is worth the selling price before they start the “But wait, there’s more!” game. If you’re the customer, just keep in mind: the seller has decided on the price, so they are not actually giving anything away for free.

Answering a Question with a Question: If a customer responds to your notification, you can assume they have an interest in buying your car — but you can also assume they have some reservations about it, since that’s normal. The difference between a good salesperson and a great salesperson, they say, is that the great one is skilled at figuring out what those reservations are and getting beyond them. This requires you to find out what the customer is thinking, and the best way is to ask questions like “What features were you looking for?” or “What are your hesitations?” If the customer asks “How good is the mileage?” it’s obnoxious to completely ignore their question, but taking it as an opportunity to fire a question back at them (“How much driving do you expect to do every week?”) can lead to valuable insights or suggest persuasive responses. For example: “If you only drive 60 miles a week, a car that gets 5 miles more per gallon will only save you about $200, but you’ll pay way more than that to find a more fuel-efficient car.”

The Scarcity Technique. If you’ve ever watched a shopping channel, you may have noticed that their inventory always seems to be getting low: “There’s only four more in stock!” This is connected to the action step in the 5-step model: when people feel like something is plentifully available and always will be, there is no immediate motivation to act now. If, on the other hand, it feels like the window of opportunity is closing fast, people will be motivated to act quickly. You have only one car to sell, so you can’t play the “only four more in stock” game, but you can hint that there are other interested customers who may snatch that car any minute now.

Us vs. Them: Have you heard the phrase “good cop, bad cop”? It refers to a technique used when a suspect is arrested and interviewed by two police officers. One officer is aggressive and threatening, and the other one intercedes on the suspect’s behalf, making the suspect feel like the friendlier cop is on their side. It’s an illusion, of course: neither cop is on the suspect’s side, but creating a common enemy can make the suspect feel gratitude toward the nicer one. At a car dealership, a salesperson may claim that they want to cut the customer a great deal but that their manager won’t let them, leaving the customer more open to whatever the salesperson charges. If you’re trying to sell your own car, you might have your romantic partner or roommate play “bad cop” and scowl at you for not asking enough for the car, then shrug your shoulders at the customer and say, “What can I do? I’m trying to help you.”

- Petty, R. E., Rucker, D., Bizer, G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In J. S. Seiter & R. H. Gass (Eds.), Readings in persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining (pp. 65–89). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. ↵

- Cialdini, R. (2001). Influence: Science and Practice (4th edition). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. ↵