Chapter 4: Listening

4.2 Components of the Listening Process

Working backwards from the goal of having a listener grasp what the speaker means is one way of examining the nature of communication. If you understand what makes it difficult for audiences to listen, you can address those barriers and craft meaningful and powerful messages.

It helps to begin by closely examining the phrase “pay attention.” The word “pay” frames it as an economic transaction: listeners pay attention to a speech just as they pay for a sandwich from a deli. It also gets away from the idea that listening is an easy process. Saying you are “just listening” hints at other activities you could be doing while you are “putting your mind at rest.” Some people listen with their eyes closed, so others can’t even tell if they are listening or sleeping. And if you think of a dog or a volleyball as being a good listener, the primary feature is that they are not doing anything else. The word “pay,” however, reminds you that the listener is doing something, and it is costing them. They are setting aside other things they might want to be doing, tuning out distractions, temporarily refraining from talking, and, if they are a good listener, cognitively processing and remembering what you are saying.

In economic transactions, though, customers pay for something for only as long as they get something out of it and it’s not too expensive. In the case of listening, hopefully what the speaker says is as nourishing or enjoyable or satisfying as that sandwich. If it isn’t, the listener’s mind will drift off, either temporarily or permanently, and they will regret making the transaction in the first place. Social norms usually dictate that they try to conceal their distraction or boredom from the speaker, and do what they can to try to look like they are paying attention — but like an electrical circuit that is interrupted, nothing is actually happening.

Taking the principle that listeners will pay attention unless it becomes too costly for them, let’s look at what those costs are. It helps to break down the listening process into component parts, and Adler and Towne identified five of them:[1]

Hearing: the physical act of receiving auditory stimuli

Attending: focusing attention and filtering out distractions

Understanding: putting mental energy into comprehending the speaker’s message

Responding: giving appropriate feedback and making sure that the message heard matches the message delivered

Remembering: A person who forgets everything that someone said to them after the conversation is over cannot be said to have listened. The point of listening, after all, is to learn and remember.

Any one of the first three elements could turn into a barrier that would prevent listening: if the listener can’t physically hear the speaker; if they are distracted by something else going on (externally, such as a siren wailing in the background, or internally, such as an empty stomach or a worry on their mind); or if they can’t grasp what the speaker is saying. Sometimes the speaker doesn’t know if listening has occurred until the audience responds, but in public or mass communication situations, response may not be possible. Most people learn early in life how to act like they are listening even when they aren’t, so nonverbal feedback can be unreliable.

One element I would add to Adler and Towne’s list is translation (perhaps as element 3-½). On its surface, “translation” usually refers to the process of taking something expressed in one language and re-expressing it in another: translating the Japanese word “yasu” into “calm” or “peace” in English or “amani” in Swahili. You might think of this as a job that only a small number of people perform, but I will take a broader view and argue that we are all translators: putting things into language that the listener can understand is an essential part of the communication process. A good neurologist speaking to a patient will try to phrase things in a way that someone without a medical degree can understand; a parent taking a 3-year-old child on an international flight needs to explain the boarding process or customs in terms the child can grasp; a customer taking their car in to get repaired must have some way of explaining what’s wrong with the car to the mechanic. When someone asks their romantic partner, “How was work today?”, unless both of them have worked the same job at the same place, the answer will require some translation.

It would be a mistake, however, to think of translation as resting only on the shoulders of the speaker. Regardless of how much effort the speaker does or does not put into making the message understandable for the listener, the listener is an active translator, interpreting what the speaker is saying in their own frame of reference. Without the ability to translate, understanding others who have led different lives and see the world differently would be impossible. When someone says “You can’t understand my experience because you haven’t lived through it,” they undermine the act of communication itself, presuming that words have no power to convey something that direct experience doesn’t teach. What would be the point of reading a story about a person climbing Mount Everest, for example, if the reader just said “I’ve never climbed that particular mountain, so I don’t understand this story”?

This also ignores the role of abstraction: a reader or listener may not share the speaker/writer’s direct experience, but if they can rise up a level of abstraction and find the universal experience in common, they can understand it: “I have never climbed Mount Everest, but I have lived through a test of my endurance, and know what it’s like to have to go on even when you think you can’t.” In other words, if the listener can connect the feeling of enduring a lengthy dental procedure to the feeling of slogging up the north face of the world’s highest mountain, they can understand a mountain climbing story even if they have never left Florida.

This does not mean, however, that everyone is a good translator. Another term for “bias” is “consistently inaccurate translation”: when a speaker says X, the listener hears Y. The listener assumes that two things are alike or connected that really aren’t, consistently ignoring evidence to the contrary. A wealthy person hearing a tale about a poor person who steals might miss that it’s a story about desperation, and instead hear “greedy person who takes shortcuts instead of working an honest job.” Likewise, a con artist might think a person who works a moderately paying job is a fool who doesn’t know what they are missing and isn’t daring enough to rebel against “the system.” The listener’s framework here prevents them from hearing the actual story, and the assumption that they already know the story’s lesson blocks them from learning a new one. This shows how listening is a key to overcoming bias and understanding others who are different from you.

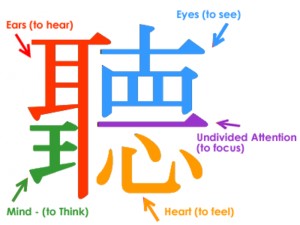

BOX 4.2: The Chinese Symbol for Listening

Readers who can only read the Roman alphabet (the script this book is written in) might not appreciate how much can be packed into symbols for words in other languages. An exquisite example is the Chinese word for listening, which sounds deceptively simple: it’s pronounced “ting,” but the symbol combines five or six different concepts. (Note: Since I am in the category of people who can’t read Chinese symbols, I have to rely on others to interpret them for me; my apologies for any mistakes or misinterpretations.) There are many websites that discuss the deeper meaning of this symbol, and interestingly, they disagree with each other — but that shouldn’t be surprising, given how much interpretation is involved in translation. These differences also contain insights, so let’s look at two contrasting discussions about the component parts of the symbol and what they mean.

SkillPacks.com identifies five elements of the symbol: ears, eyes, mind, undivided attention, and heart. In order to listen well, you must hear the person with your ears, see them with an undivided focus, and listen with your heart as well as your mind. They depict this visually as:

Tani Du Doit, from the website The Restore Method, points out that the lower left symbol can be interpreted as “king” instead of “mind,” with the implication that the speaker should be treated like royalty, and should be obeyed. Think of how helpful it must be to have a written language that reminds you that listening is not a simple or effortless process.

Other sites note that the upper right corner, the symbol for eyes, has the number 10 above it, suggesting that the listener should observe the speaker “as if you had 10 eyes instead of just two” (i.e., very carefully).

- Adler, R.B., & Towne, N. (1996). Looking out, looking in (8th ed.). Harcourt, Brace. ↵