Chapter 2: How Communication is Studied

2.1 Everyone Is a Student of Communication (Just Not in School)

When I enrolled in Temple University as a psych major in the early 1980s, someone suggested I take a course in public speaking, which sounded like a good idea. In those days, course catalogs were printed books, not searchable databases, so my question was “Where do you take a public speaking course from?” That’s when I discovered that there was a major called “Speech,” and that right next to the public speaking course were classes in other things that sounded very interesting: small group communication, family communication, argumentation, persuasion, and more. I took three speech courses that first semester, switched my major, and never turned back. But a curious thing happened: the name of my academic discipline kept changing. I received a bachelor’s degree in “Speech,” a master’s degree and doctorate in “Speech Communication,” and I now teach in the “Communication Studies” department.

I discovered that the discipline was much older than I first thought; its history is hard to track because of all those changes (including names I had never heard before: see below). This history illustrates the identity crisis long faced by communication as an academic field. When I was an undergraduate, some older adults would ask me what I was studying in school, and if I said “Communication” (no “s”), they would reply “Communications? Oh, you mean radio.” Why did they make that assumption? Because they knew someone who had served as a “communications officer” in World War II, in charge of radio transmissions. I would tell them “No, radio is part of the Radio-Television-Film major, not mine.” Others heard the word “Speech” and thought it meant helping people overcome speech impediments and regain their ability to talk after a stroke, and I would say “No, that’s something else called Speech and Hearing Science.” Meanwhile, I couldn’t help noticing that much of the material from my speech textbooks was borrowed from social psychology, philosophy, sociology, English, linguistics, journalism, political science, and a wide range of other academic fields. Where are the boundaries of this particular discipline?

Ultimately, drawing precise boundaries around “Communication Studies” is unnecessary, and even counterproductive. Communication is a universal endeavor: everyone on earth does it (even if they cannot speak), and communication affects every human activity. To put it another way, although only a small portion of college students call themselves “Communication Majors,” everyone is a student of communication in some way. It would thus be absurd to draw a thick wall around what a certain set of scholars study and say “That’s our turf — stay off of it.”

A calculus or nanotechnology professor may say to new students, “You don’t know anything about this subject, so let’s start at the very beginning,” but instructors in communication know that all of their students have been learning about communication since they were babies. Leaders, from low-level managers to rulers of empires, can benefit from taking courses in leadership, but they learn about leadership communication every day even without such courses. Most soccer coaches and bridesmaids who give speeches never took a college public speaking class; juries reach unanimous verdicts even if none of their members has studied group decision-making; salespeople learn tricks of the trade without reading a persuasion textbook; and even without the benefit of a media literacy course, any television watcher can notice patterns in what they are seeing. In every case, however, someone who does take a course in one of those areas should have an advantage. And, of course, scholars who study the communication process have brought us insights that filter into the general knowledge, reaching students and non-students alike.

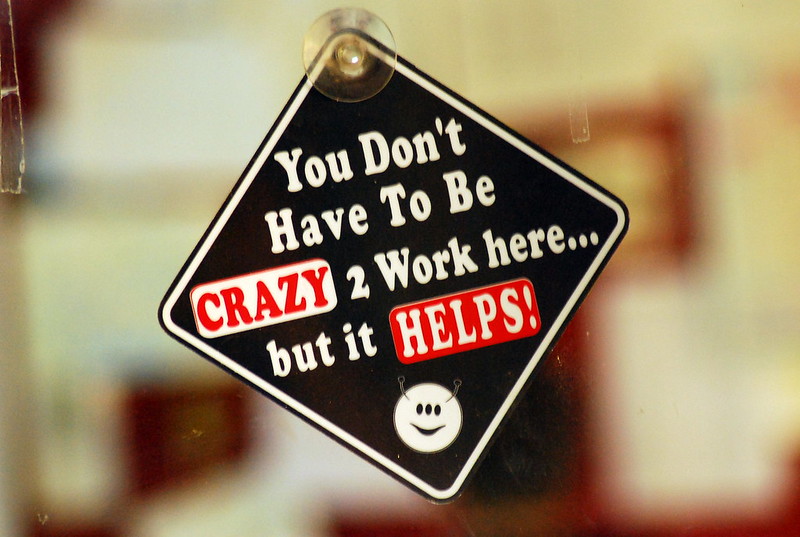

You may have seen a cynical expression in offices: “You don’t have to be crazy to work here … but it helps.”

Communication scholars could turn that expression around to say “You don’t have to read textbooks to learn about communication … but it helps.”