Chapter 18: Media Part I – How to Think About Communication Technology

18.3 Dimensions of Media

Reach & Ratio

J.B. showing his cactus photos to a few friends and family members illustrates that, before electronic media came along, the number of receivers or audience members a typical person could reach was very limited. Even if you were a presidential candidate, before microphones and speakers you could only speak to a few hundred people at a time, depending on the strength of your voice. There were forms of mass communication 150 years ago — printed books, newspapers, magazines — but they did not allow for immediate communication or rich channels; they contained only words and, occasionally, pictures.

The advent of radio and television brought with it a new word, broadcasting, to refer to the ability to reach a very broad audience in real time. This made an enormous difference in fields like politics, where a leader could address an entire country at once, or entertainment, where a singer like Ella Fitzgerald or Elvis Presley could reach into millions of homes. The ratio of senders to receivers, in other words, jumped from 1-to-hundreds to 1-to-millions, and has continued to climb.

J.B. was accustomed to being only in the audience role, one of millions of watchers of television shows or listeners to the radio or records; he never had the opportunity to be on television or the radio himself. In 1965, the ratio of senders to receivers was extreme: while almost everyone was in the audience role, only a very small, select group of people got to create the content. The technology simply didn’t allow everyone to be in the sender role: the frequency range of radio stations went from 88 megahertz (MHz) to around 108 MHz, and radio stations with frequencies too close to another station would cause interference, so a particular geographic area could support no more than 20 radio stations. With the limited number of hours in a day, it’s clear why there just wasn’t room for most people to get on the radio and express their opinions or play a song. In America, the question of “who owns the airwaves” was resolved in favor of the government, so anyone who wanted to create their own radio station had to get a Federal Communication Commission (FCC) license, and other countries made equivalent decisions.

When television came along a few decades later, it followed a similar path: there were only a few channels, owned and operated by media corporations but under the watchful eye of the government, which could take away their FCC license. The owners of those media companies, not to mention the people they chose to put on the air, were mainly white men, and as a result, minority voices were seldom heard and the representation of other races, gender categories, and disabilities was rare or problematic.[1]

The dominance of gatekeepers changed with the introduction of digital media, which removed the physical limitations of earlier forms of media. Instead of being restricted by frequency ranges in the airwaves, cable television allowed for hundreds of channels. And once the internet became available to the general public in the mid-1990s, the capacity for creating new channels became virtually limitless. Anyone could set up their own website, which initially did cost a sizable sum of money, but nowhere near as much as it would cost to create a television station — not to mention the fact that websites didn’t require getting an FCC license. Then, shortly after the turn of the century, social media took it a step further, establishing common platforms where individual users could create their own personal websites or channels: MySpace (created in 2003), Facebook (2004), and YouTube (2005) paid for the basic technology, and individuals could create their own pages and decide what content to put on them. While some of the terminology carried over, the capacity was totally different: J.B. was able to get five “channels” on his television, but Jarice was easily able to set up her own YouTube “channel” (alongside 114 million other YouTube channels).

To say that these developments changed the ratio of senders to receivers is putting it mildly: everyone could potentially become a source of media messages, and the reach wasn’t limited by geography. Since the cost of producing and distributing media content also dropped drastically, the sender side no longer included just media moguls and corporations. Not only were many more people allowed to jump into the game, but the demands for large audience numbers went away.

In the old days of American television, when advertising paid for everything, advertisers were highly motivated to find out how many eyeballs their ads were reaching. If the research didn’t indicate that the advertising was worth it (i.e., only two million people were watching your show, or those who did watch didn’t go out and buy the brand of detergent advertised in the commercial breaks), the advertisers would stop buying ad time and the shows would lose funding.

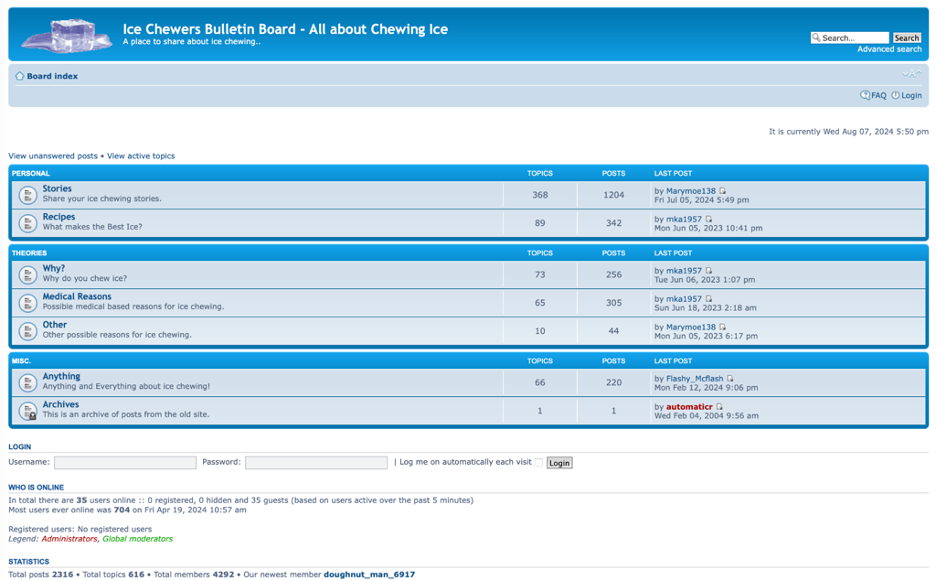

The new model, in contrast, allows for narrowcasting: content that reaches only a few hundred people yet can still be economically viable. If someone wants to host a discussion board for people who really love chewing ice, why not?

To save you the trouble of trying to read the tiny print on the bottom, it includes the stats “In total there are 35 users online” and “Most users ever online was 704 on Fri Apr 19, 2024.” Reaching only 35 viewers is still worth it to these ice chewing fans to keep the site running.

If there are no web hosting costs, the numbers can be even smaller. In the 2018 film Eighth Grade, the title character Kayla (Elsie Fisher) posts motivational videos on YouTube and is discouraged to find out that her videos get exactly zero views. How long will she continue to make videos that start with the cheerful greeting “Hey guys” once she has found out that there are no “guys” and that her entire audience is imaginary?

Yes, modern technology allows for the potential of everyone being in the sender role and achieving huge audiences, but in reality the sender-receiver ratio is still extreme. The “1% rule,” sometimes expanded to the “1-9-90 rule,” suggests that only 1% of any online community regularly contributes content, another 9% contribute sporadically, and 90% are content with being “lurkers,” reading and watching but not posting anything.[2] Precise numbers vary depending on the context, but the general principle that far fewer people provide content than consume it seems very stable.

Gatekeepers

In J.B.’s day, when media was expensive and controlled by corporations, J.B. knew that no matter how good a jazz singer he became, he would never be able to record an album without going through a gatekeeper: a record label agent who would decide if his voice was worthy of ending up on a vinyl record. This was not a new idea: hundreds of years earlier, very few people owned a printing press, so an aspiring writer had to convince a publisher that it was worth the investment to print copies of their book (and not just one copy, but enough to make the printing run worth the time and effort). If those publishers didn’t want to print your book, the “gate” was shut and there wasn’t much you could do about it. When newspapers came along, the picture stayed largely the same: newspaper editors had the power to decide what would appear in the daily paper and what wouldn’t, which meant having considerable power over the public consciousness and opinions. Electronic media didn’t change the picture: radio and television stations all had employees whose job was to decide what got on the air and what didn’t (and, as mentioned earlier, to worry about the FCC pulling their license).

There were several reasons gatekeeping was a necessity:

- The limited number of hours in the day. Not every wannabe talk show host got their chance, and not everyone who thought they had experienced a significant news event (“I was stuck in a traffic jam for 45 minutes!”) got to tell their story;

- Production expenses, which meant that every time a media company did decide to invest in a particular piece of content, they were taking a financial risk;

- Limits on the public’s capacity for following the “stars” in any medium, which meant that constantly introducing new performers into the picture wouldn’t work. If audiences loved a familiar set of movie stars, for example, casting agents had to be mindful of the rate of introducing new actors into the movies without bumping off old ones.

The upshot was that the tastes, preferences, and prejudices of those gatekeepers dictated what everyone got to see and hear: if a record company executive didn’t like your band because “guitar groups are on the way out” and they thought Brian Poole and the Tremeloes were a safer bet, well, sorry Beatles, but no record deal (and if another record company hadn’t made a different decision, the world might never have heard “the most influential band of all time”). When the Wright brothers first achieved human flight in December 1903, none of the newspapers thought that was worth reporting in the news.

Sure, human beings get it wrong sometimes, so the interesting question is not why they aren’t 100% perfect at predicting success, but what criteria gatekeepers use to make their decisions. When the film Killers of the Flower Moon came out in 2023, the question it raised for many people was why this series of murders of Native Americans was “nearly erased from US history ”: at least 60 wealthy Osage tribe members were murdered, and the newspaper publishers decided “That’s not newsworthy.” Gatekeepers, in other words, have always decided what the public gets to hear.

Along with the sender-receiver ratio, the need for gatekeepers also changed drastically in this century. As noted, social media sites allow anyone to post (almost) anything, meaning that any garage band could put their songs on YouTube without having to get signed to a record label. At the same time, production costs went down and cheap or free tools became available to the public, so that band can record a whole album without having to shell out big bucks for recording studio time. Jarice can sing a song in her bedroom, edit it herself, and post it online without going through any music executive or talent scout. Print on demand means that a print shop doesn’t have to invest in a run of a thousand books; it can wait until someone orders a book and then print one copy of it for that buyer, which made self-publishing very viable. Websites now allow painters to sell art directly to buyers without having to go through galleries, and people with ideas for a television series can shoot a web series without going through a TV studio.

This suggests that the era of gatekeepers is over, and that the barriers to becoming your own superstar have been removed. While this is theoretically true, once again the practical reality looks different, as William Deresiewicz demonstrates in his book The Death of the Artist.[3] In fact, he argues that it is much harder for musicians, authors, playwrights, and dancers to have a career now than it was in the gatekeeper era, and reports that the number of musicians and authors who can make a living at their craft has recently dropped by 24–30%.[4] The number of musicians who are able to distribute their music to the masses has exploded (as of 2017, Soundcloud carried music by ten million artists), but that doesn’t mean anyone ever hears that music, and the musicians themselves bear the weight of promoting their work instead of having a record label doing it for them. In Deresiewicz’s words, “The good news is, you have the freedom to pursue new opportunities. The bad news is, so does everyone else. The good news is you can do it yourself. The bad news is you have to.” He also points out that the need for gatekeepers did not go away; it just shifted away from the handful of corporate employees who used to do it. He writes:

You don’t have access to the audience if the audience can’t find you, and nobody can search for you unless they know that you exist. For artists, the more noise there is in the system, the more valuable become the players who can cut through it, which mean the major corporations, old and new, of the culture industry. For the audience, the more valuable become the players who can filter it, who perform the work of “curation,” of selecting and sorting. Whatever we’d prefer to think, the gatekeepers are not dead (a curator is just a gatekeeper that you happen to like), nor is it possible to imagine how they ever could be. (p. 61)

He also adds that gatekeeping is no longer primarily performed by humans, but by algorithms telling us what we will probably like. As media scholar Peter Gregg put it, the old fashioned habit of walking into a physical bookstore and browsing the shelves has been replaced by algorithms that learn what you like and then just keep presenting you with “more of the same.” That’s nice if all you want is slight variations in what you already like, but if you want to broaden your horizons and make surprising discoveries, those algorithms work against you, not for you. In a similar way, the film industry still includes many human gatekeepers, but the economics discourage risk-taking on truly creative and novel movies and instead favor an endless string of sequels, prequels and remakes. In Gregg’s words,

Humans, I think, like to explore, like to make connections, like to learn — but that stuff is longer term, that stuff requires work. We have technological practices that minimize work and maximize short-term feel good, but at the end of it you’re left with not much.

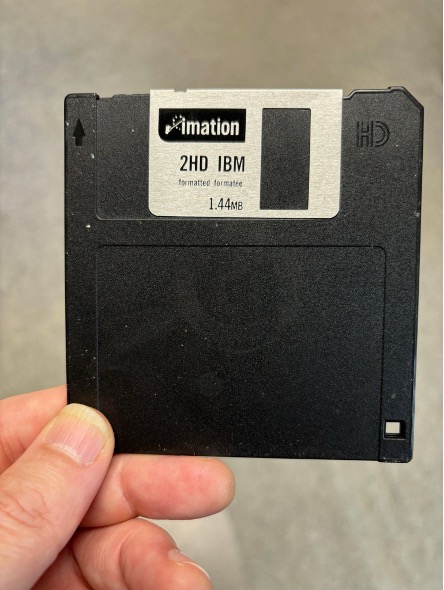

Permanence

In 1994 I finished my Ph.D. dissertation, the biggest project I had ever completed, and I carefully stored it away in a fireproof box . But what, exactly, did I put into that box? A 3-1/2” high-density floppy disk containing digital files written in a software called MacWrite II. Only a few years passed before I realized that I no longer had any devices that had a floppy disk drive, and even if I did, I couldn’t open the files because the software was obsolete. Good thing I printed my dissertation out on old-fashioned paper! Sometimes I pull out that disk, hold it up in front of my students, and say “I am holding my dissertation in my hand — yet for all intents and purposes, it has disappeared from the face of the earth.” What I thought was permanent in 1994 turned out to be not permanent at all.

Our earlier discussion of the “document” implied that if communication is stored in some form of media, it’s permanent. There are written documents that still exist after 5,000 years, such as the Kish tablet (found in modern day Iraq), and paper documents that are more than 1,000 years old. When we get to the digital era, however, the permanence question gets a little foggier, which is why I ended Jarice’s story with the question about whether her social media posts will still be accessible to her great-grandchildren the way her great-grandfather’s letters are.

Again, you can approach this question from a theoretical perspective or a practical one. You may have heard the rule that whatever you post online is there “forever,” so you should be cautious about anything you upload. It is true that deleting something you posted is impossible if it has been reposted on numerous other sites, and also that it can be accessed using the web archive “wayback machine”. On the other hand, many websites are geared toward the immediate and posts are sorted by date, which makes it difficult to access anything older than a few days. Yes, that “needle” (something you posted four years ago) is still in that haystack, but it’s buried so deep that no one is likely to ever see it again.

A related question is: do people want their digital materials to be permanent? Many litigants caught in a lawsuit have discovered the hard way that deleted emails can be recovered, leading them to wish that email wasn’t so permanent. In 2012, CIA Director David Petraeus was found to be having an inappropriate relationship with Paula Broadwell. One thing they thought would protect them from scandal was an email trick: instead of actually sending emails to each other, they wrote emails that would sit in the “Drafts” folder of a shared account, and once the other person had read a message they would delete it without the email ever being sent. The fact that these messages were still found shows you that even this seemingly fleeting form of communication was more permanent and detectable than a CIA director thought it was.

Even if you aren’t trying to hide anything, you may prefer non-permanent channels of communication just because you don’t see a need to have a lasting record of the conversations. One 30-year-old I talked to had tried numerous different social media platforms, but settled on Snapchat specifically because the messages only stay up for a day. When you post on social media, is your goal to create a record of your life, or just to get through the day?

Richness

The next chapter explores Media Richness Theory, so for now I’ll just note that different forms of communication technology are capable of carrying different kinds and amounts of information. In 1865, you could send a telegraph message from the east coast of the United States to the west coast, but that message consisted only of Morse code dots and dashes, which were translated into written words. When film was first invented, it took decades to figure out how to add the element of sound. Now, you can livestream high-definition videos with stereo sound, an infinitely richer form of communication. Well, perhaps I shouldn’t say “infinitely,” because that technology has its limits, too: as of this writing, you can’t transmit aromas or tastes that way, or touch someone 1,000 miles away. The point is, when comparing different media formats, including new ones that will be introduced in the future, richness is one of the dimensions to consider. In Chapter 19 we’ll look at its use in communicating particular kinds of messages.

You might think that the creation of richer forms of communication technology would mean the death of older forms, but it hasn’t. Vinyl records were replaced by compact discs (CDs) in the 1980s, and people who had been frustrated by the pops and skips[5] were greatly relieved, and impressed at the perfection of digital audio. Then CDs were replaced by digital files, so it looked like the forward march of music formats was leaving a trail of corpses behind — until those corpses came back to life. As of March 2023, vinyl record sales outpaced compact disc sales, and now 180 million vinyl albums are produced every year. Low-quality Polaroid cameras were a cheap alternative to more expensive cameras in J.B.’s day, so it’s no wonder that affordable digital cameras wiped them out, leading to Polaroid declaring bankruptcy in 2001… and then the brand was revived and is still alive now.

In other words, people who declare old technology “dead” have sometimes had to correct themselves — it’s only “mostly dead.” But as Miracle Max said in The Princess Bride, “mostly dead is slightly alive” and can come back with a roar. Why doesn’t digital perfection replace less perfect media? Perhaps because people don’t always want things to be perfect.

Personalization

One last variable that you can use to sort different forms of communication technology is the level of personalization: movies, television shows, books, podcasts, and billboards are designed for mass audiences, while letters, emails, texts, voicemail messages, and video calls are intended for particular people and can be tailored to their specific needs and tastes. This may or may not be related to the ratio question: if you’re sending a message to thousands of recipients, there’s usually no practical way to adapt it to individuals (although it may be possible to insert their name into a mass-produced message, making it look like it’s individualized). But the option to send it to one person vs. 5,000 is not built into the medium itself: a sender can craft a voicemail for one recipient or make a recording and send it to thousands of phones at once. The word “intimacy” implies one-on-one communication, but a gifted performer can create the feeling of intimacy even in mass media messages, such as a singer who makes millions of audience members feel like the song was written “just for them.”

- For a thorough exploration of the historical depiction of different races, gender categories, disabilities, and age groups in American media, see Luther, C.A., Lepre, C.R. & Clark, N. (2012). Diversity in U.S. mass media. Wiley-Blackwell. ↵

- Arthur, Charles (20 July 2006). "What is the 1% rule?". The Guardian. ↵

- Deresiewicz, W. (2020). The death of the artist: How creators are struggling to survive in the age of billionaires and big tech. Henry Holt & Company. ↵

- Deresiewicz, p. 42. ↵

- It’s curious that the phrase “sounding like a broken record” has survived in the English lexicon long after the problem it refers to became unknown to most speakers. If you’re not aware, a vinyl record consists of a single groove cut into plastic, and you play it by dropping a delicately balanced diamond needle into the groove (starting on the outside of the record, working its way to the inner ring), with the vibrations from the needle translating into sound. Imperfections in the plastic would make the needle bounce up, and instead of landing back where it started, the needle would go back one revolution and play that segment again, until it hit the imperfection again and jumped back. The listener had to hear the same two-second loop again and again until they got up, walked over to the record player, and moved the needle into a later slot. The needle also sometimes left the groove and skidded diagonally across the record, causing a horrible, non-musical screeching sound nobody wanted to hear … until DJs and sound editors decided to insert the “needle scratch” sound into songs and movies. ↵