Chapter 1: What is Communication?

1.2 Defining Communication

First, let’s try to define what communication is, and some of the different ways to represent the process.

In Scenario 4, Sonja’s partner did nothing but stand motionless and expressionless for a moment before walking inside the house, but Sonja got the message, loud and clear, that her choice of car color was not well-received. Silence and lack of response can communicate volumes, but if a neighbor happened to also step out of their door at the same time, and stood in a similar way and walked back into the house at around the same time, Sonja wouldn’t interpret that neighbor as sending a message. The problem with trying to come up with a definition of communication, in other words, is that anything can potentially convey meaning — words, lack of words, behavior, lack of behavior, time, space, silence. Have you ever been in a waiting room with a stranger and started wondering if they were sending you any kind of signals, or worried that they thought you were sending them signals? The command “Don’t communicate” may be impossible to obey, which suggests that it’s also impossible to study communication since it’s so all-encompassing. To make it a manageable topic to study, you have to put some boundaries and limitations around the definition of “communication” — when it occurs and when it doesn’t, and what is happening when it does.

Thankfully, scholars have been working on models of communication since the 1940s. The curious thing is that the first scholars to tackle the subject of communication models were not concerned with human beings talking to each other. They were looking at the budding field of electronic communication, and how a message could be sent electronically without things going wrong. If you type a text message into your phone and hit “Send,” what exactly happens, and what prevents the message from ending up as an incomprehensible mess of gibberish symbols at the other end?

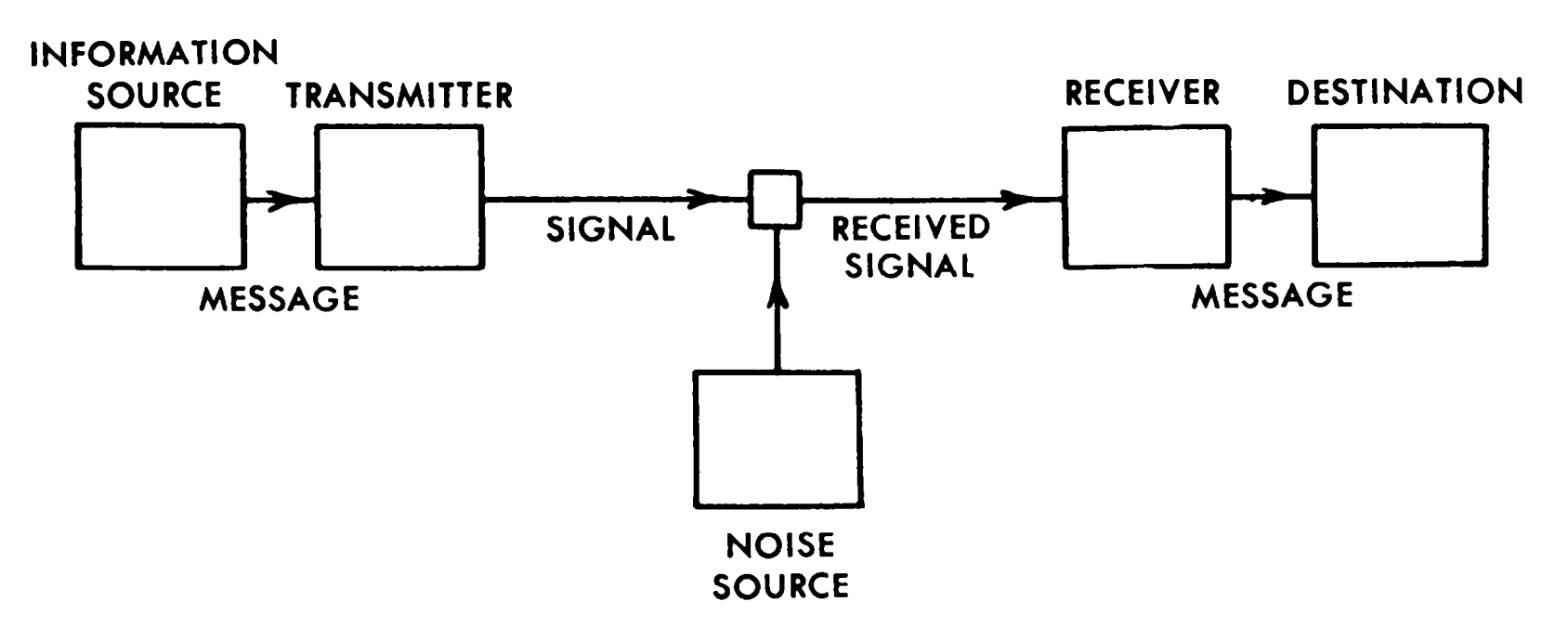

One of the pioneers of this field was a mathematician, Norbert Wiener, who is considered the originator of cybernetics (communication in the electronic sense: sending and receiving electronic signals). He broke the communication process down into components such as source, receiver, signal, filter and noise. In 1948, another mathematician, Claude Shannon, refined this into a model of communication that has been put forth as the starting point for the systematic study of communication.

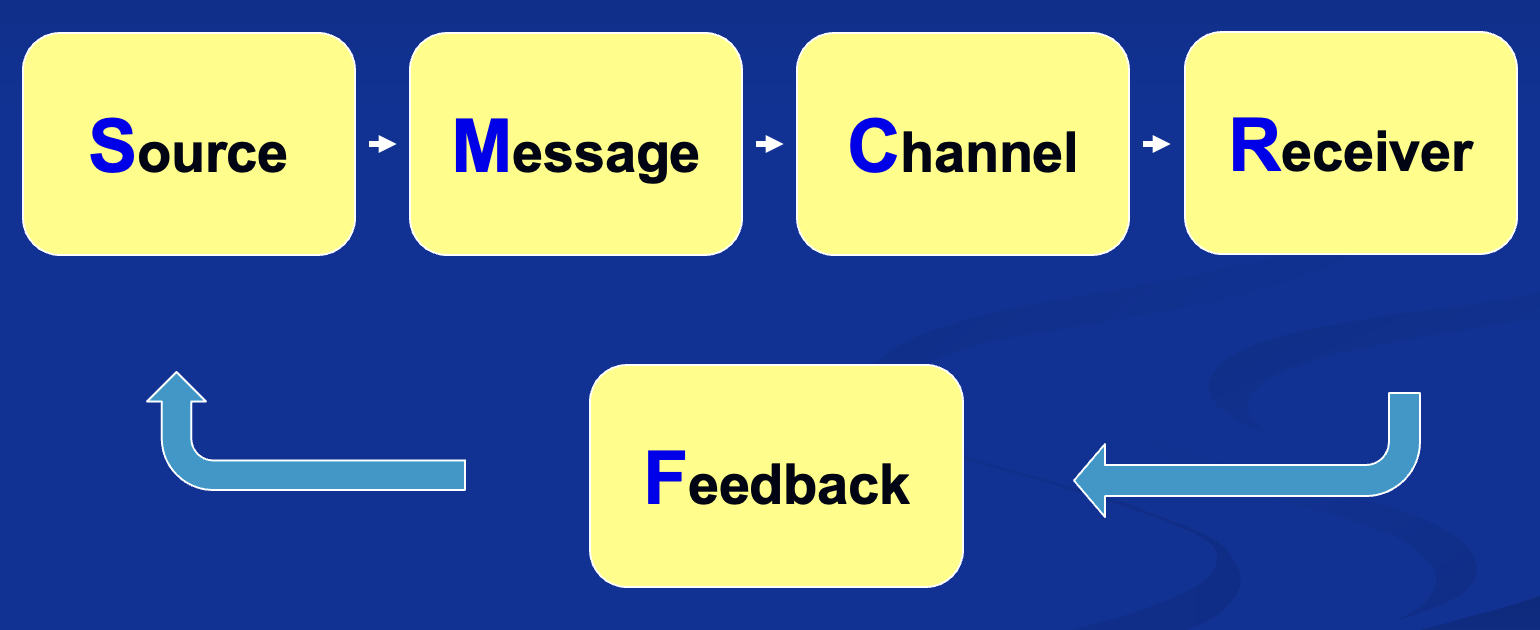

Like Wiener, Shannon was not looking at human beings talking to each other, or at anything like the four scenarios that began this chapter. But other scholars who were interested in people talking to each other found it useful, and realized that it could be adapted to many forms of human — and even animal — communication. In the 1960 book The Process of Communication, David Berlo reframed Shannon’s model as the Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver (SMCR) Model, in which communication occurs when a source sends a message through a channel to a receiver. Later scholars added one more component: feedback, the mechanism necessary for the sender to find out if the receiver got the message, and perhaps what they thought about it.

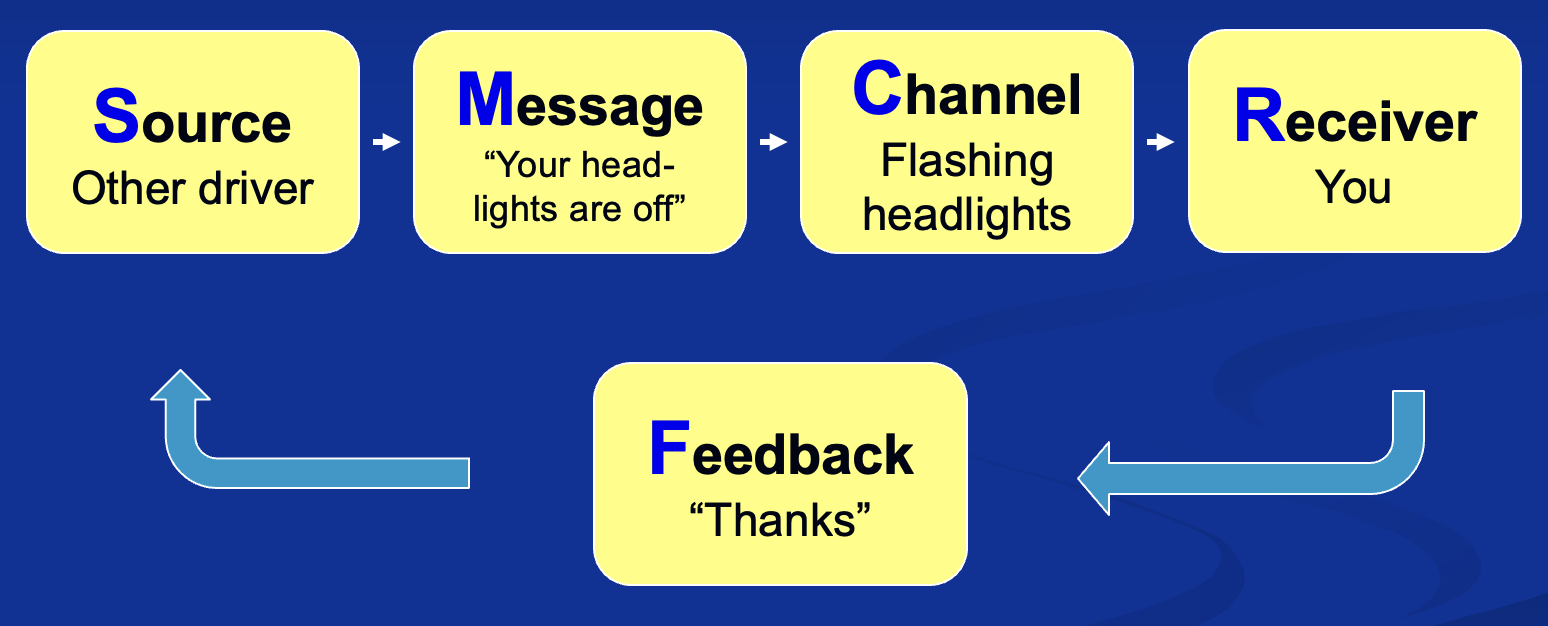

On its face, the model does not tell us much, but it provides a framework for thinking about the component parts of communication, and gives us terms that I will use throughout this book. Returning to the four scenarios, the first one can be depicted as:

The model also shows how the communication process can fail, either because one element is missing or because something just goes awry. Scenario 1 ends with you saying “Thanks,” but the other driver never hears it, so that can hardly be counted as feedback. That’s a channel problem: quietly speaking a word to another driver when your windows are rolled up doesn’t work. In Scenario 2, before her husband even finishes his sentence, the elderly woman knows, because of context, what he is talking about; they’ve had this same conversation before. Mathematicians like Wiener and Shannon didn’t address situations where the receiver understands the message even though the source didn’t finish sending it.

In Scenario 3, the issue isn’t the channel, it’s the fact that the message sent by the apologetic celebrity is not the same as the message heard by the home viewer. This is called a “fidelity” problem in the mathematical model, but it’s always good to keep in mind that in many situations in life, the message sent does not equal the message received. In Scenario 4, Sonja gets the message that her partner hates the new car color, but that’s only based on what her partner did not say or do.

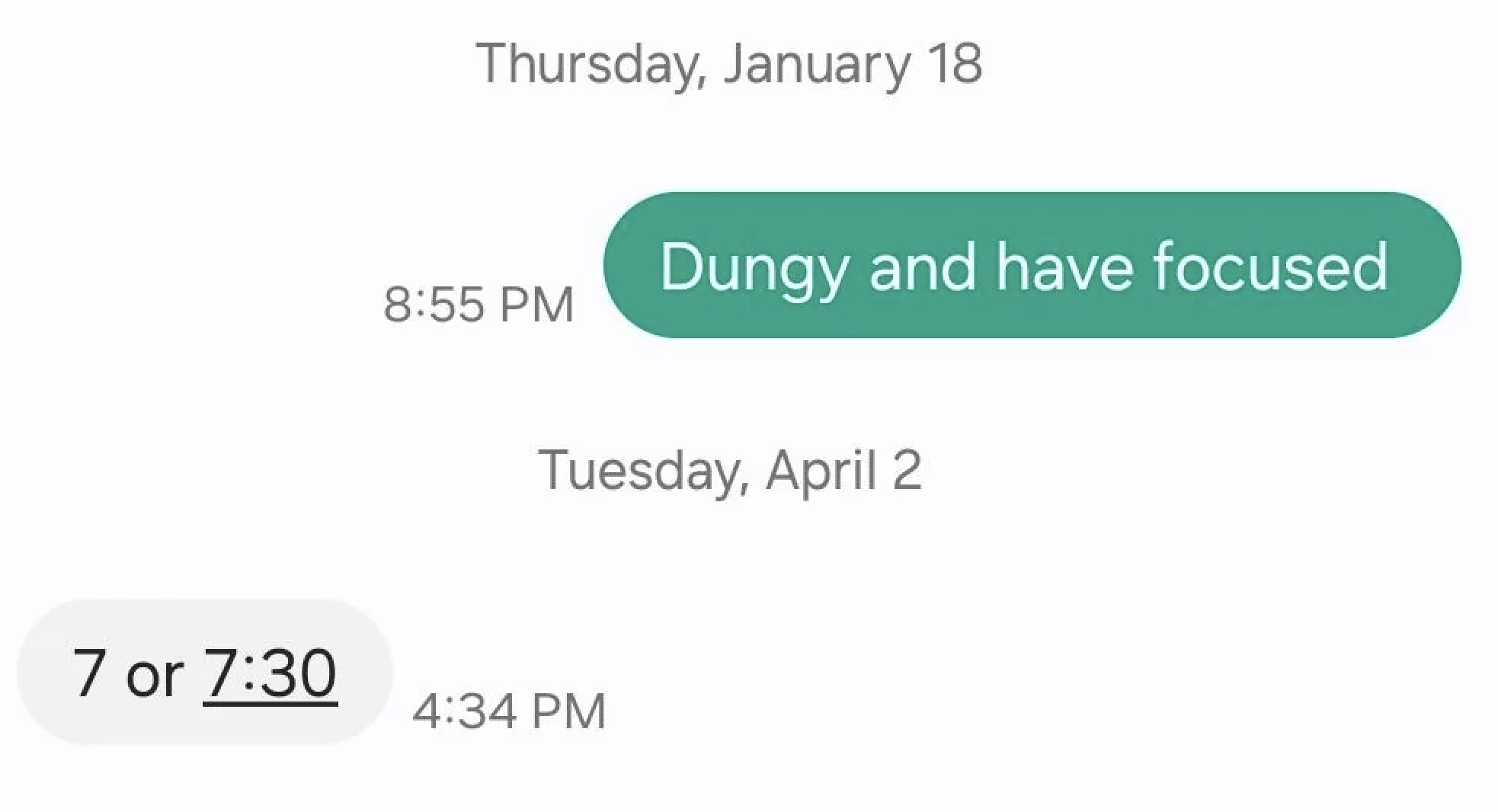

Starting with an electronic or mathematical model to try to understand the communication process is helpful, but as we can see, it has inherent limitations. Think about texting. You can’t assume that good communication has occurred just because a text message that appears on a recipient’s screen is identical to the message sent by a source.

The S-M-C-R model is an example of what I’ll call the “Voicemail Model” (in academic circles, this is known as a “Transmission Model”): if you call a phone number and the person doesn’t answer, you figure out what message you want to leave, say it at the proper time, and your job is done. This ignores many aspects of the actual communication process.

A more sophisticated model is one I’ll call the “Birthday Present Model,” which views communication as being like giving someone a wrapped gift. First, the sender has to figure out how to “encode the message” (wrap the gift): what are the right words to convey my meaning? What about nonverbal communication — tone of voice, facial expressions and gestures? Then the recipient has to “decode the message” (unwrap the gift), figuring out what the sender meant. This model puts much more emphasis on the receiver, and recognizes that listening is an active process (SEE Chapter 4: Listening). It also sheds light on how complex the encoding and decoding process can be. In Scenario 1, you may or may not know what an opposing driver means when they flash their headlights: is it a threat of some kind? A thank you? If the communication channel was more complex than a simple headlight flash, it might make the meaning clearer… or muddier. If the sender and receiver come from different cultural or linguistic backgrounds, the risk of misunderstanding is great.

In the 2021 film Dune, Duke Leto Atreides takes over as the new ruler of a desert planet, and his first encounter with one of the natives is highly charged. The native, Stilgar, looks at the duke and then spits on the ground. In many contexts this would be considered an insult, and a bodyguard draws his sword. But another person present, Duncan, has studied the culture, knows what this means, and replies, “Thank you, Stilgar, for the gift of your body’s moisture. We accept it in the spirit in which it was given.” Once he learns what spit means in this extremely arid environment, the Duke also spits and a new alliance is formed. You can watch this conversation here:

Even when we factor in the process of encoding and decoding, however, this approach oversimplifies the communication process, and masks the fact that communication is not really a process of sending anything at all: it’s a process of mutual construction. I’ll call this process “The Lego Model” (scholars call it the Constitutive Model). The name is based on a classroom exercise I use to demonstrate the nature of communication. I take two tables and two chairs, facing away from each other, and ask for two volunteers to sit at the desks. I then give them each a small pile of Lego blocks, and ask Volunteer A to build something out of them, called a “construct.” Then the true exercise begins: Volunteer A must talk Volunteer B through the process of building the same construct with their Lego blocks, but without turning around to peek. Volunteer B is allowed to ask as many questions as they want, and it quickly becomes a two-way conversation. It generally takes about 20 minutes for Volunteer B to recreate what Volunteer A built in seconds, and most of the time the constructs are fairly close to each other.

It’s not meant to be an impossible game, but it does illustrate what communication really is, which can be summarized roughly as: “Communication is a process in which one person with a construct in their mind uses symbols such as language to try to get another person to formulate the same construct in their mind.” You can’t transfer thoughts directly into someone else’s head — and you can’t see into their head to see if their construct matches yours — but if the conversation goes on long enough, you can be reasonably assured that you’ve achieved mutual understanding.

In order for this to work, however, there are several conditions:

- You need a shared vocabulary. Even if you played with Legos often, you probably don’t have a name for the piece with eight circles in four rows, or one with a rounded edge, so students have to make up a lot of new terms.

What do you call this piece? Vocabulary doesn’t only refer to the pieces: when Volunteer A says “Take the red four-hole piece, and put it straight on top of the green piece, sticking out two holes over the front,” Volunteer B needs to understand what terms like “straight” and “sticking out” and “front” and even “red” mean

- In normal conversation, people don’t take 20 minutes to ensure that their construct looks like yours; they just move on at a steady pace, assuming there is mutual understanding until they discover a problem. Someone says “Mothers! You know what they’re like!” and another person replies, “Yeah, mothers! I hear you,” instead of saying “No, exactly what do you mean? What are mothers like?” And even if they explain “Oh, I mean mothers are loving,” that doesn’t guarantee that the other person has the same idea of what “loving” means.

- The building blocks are experiences, and in order for people to communicate effectively, it helps for them to have the same set of blocks. (I actually play a trick with the students: the sets of Lego blocks are almost the same as each other, but not quite). Does that mean it’s difficult or impossible to communicate with someone who does not have a background identical to yours? Of course not, but it does mean that when communicating with someone whose life has been very different from yours, it may take more work to find those shared building blocks. If someone says “It feels like a Friday today,” that will mean nothing to someone who doesn’t divide their time into seven-day weeks or get weekends off from work. The first person would need to articulate their feelings a little more: “Today feels a little more relaxed than usual, which is a nice but somewhat disorienting feeling.” The feelings of being relaxed or disoriented are universal regardless of one’s employment situation. (see Chapter 4.2: We Are All Translators).

- You have a construct in your head of the person you’re communicating with, and who they are. When you interact with another person, whether a stranger or a family member you know intimately, you’re not talking to the actual person: you’re talking to your Lego construct of that person — the way you perceive them, and the assumptions you have about them. These constructs may not be accurate, but if a person is heavily invested in a particular image of another person, the construct will block their view of reality. For example, in the Harry Potter series Harry’s Uncle Vernon and Aunt Petunia think of Harry as incompetent and worthless, and see their son Dudley as a perfect angel. Even when Dudley shouts in their faces, Vernon and Petunia are so invested in their image of their child as an angel that they can’t recognize him for who he is.