Chapter 17: Conflict

17.3 Conflict Styles

In 1995, trial lawyer Gerry Spence published a book with a promising title: How to Argue and Win Every Time: At Home, At Work, In Court, Everywhere, Everyday. No wonder it became a bestseller: who wouldn’t want to win every argument every time? Well, just as there are people who like their thermometer set at 65 degrees, there are people who do not want to win every argument. Why not? Because when it comes to conflict, “winning” isn’t everything for them: they are also concerned with other things, like getting along with people. Some people care about relationships so much more than they care about the topic of the conflict that they will automatically concede defeat: “Sure, we can do it your way.” Others never concede, and want to get their way at all costs. Many people are in-between, fighting to win on some points but giving up on others. And others adapt their style to the situation, being more concerned about relationships in one context and determined to win in another.

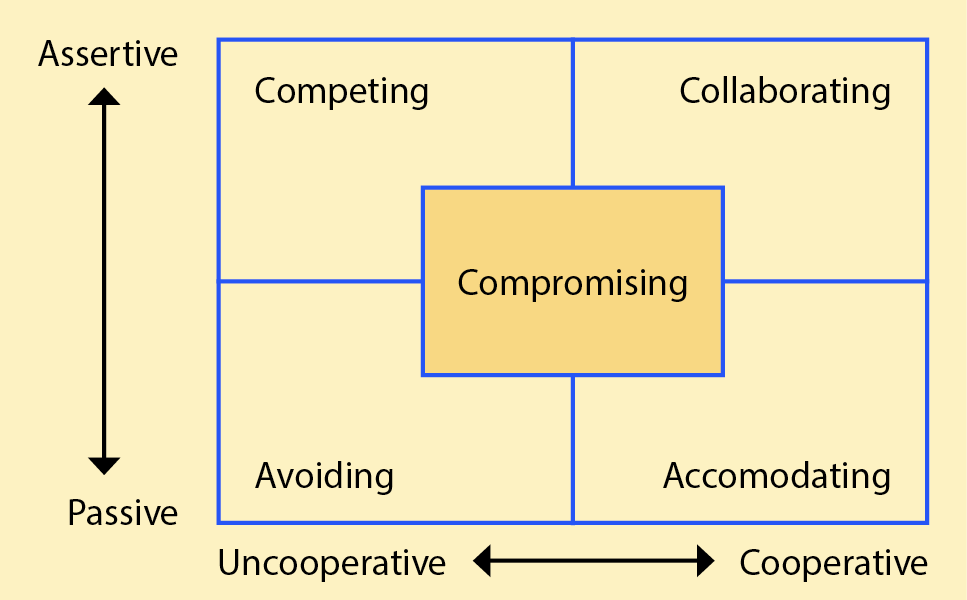

This observation led several different scholars to create a two-dimensional conflict grid, depicting these two concerns — getting your way, and getting along with others — as vertical and horizontal axes. The most famous of these models was developed by Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann in 1974.[1]

Is this grid a depiction of personality types and preferences (different kinds of people), or does it depict strategies that anyone could choose in a particular situation? Although people could identify their preferred style by looking at the grid, it is probably more fruitful to think of the elements in the grid as choices a person could make in a conflict. Research has shown that, personality differences aside, people switch styles frequently in conflict situations. As Kramer and Bisel put it, “Our preference and self-perceptions about conflict management can change rapidly.”[2] Let’s look at the elements one at a time, exploring the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Competing style is highly assertive, concerned with getting your way but not concerned with how this will affect relationships. This style is captured in the expression “It’s my way or the highway!”

If you have positional power and you are sure about your ideas, this is the way to go: you don’t want to let others with weaker ideas get in your way, nor do you want to waste a lot of time gathering input from others that you won’t use. Steve Jobs of Apple Computers was famous for being a visionary and a genius at knowing what the public wanted, and he was notorious for butting heads with engineers who didn’t like his ideas and kept telling him why they wouldn’t work. If you have an iPhone in your pocket, that’s partly thanks to Mr. Jobs adopting the competing style.

One more advantage to consider for this dictatorial style is that it’s quick: giving orders and having people obey them is much faster than talking everything through in a democratic fashion.

What are the style’s disadvantages? Some people with this aggressive style are not as smart as they think they are, and their ideas should not be adopted. In the realm of organizational communication, there has been a gradual shift over time from thinking that the Big Boss must be the smartest person in the room, and thus should give all the orders, to thinking that gathering input from everyone is a more productive approach. (This shift happened at the same time that a lot of countries changed from kingdoms to democracies.) Also, because the competing style is low on the dimension of cooperation and concern for relationships, it can lead to a lot of unhappy people. Employees quit and spouses file for divorce, or, at the very least, they might stop offering their opinions.

Accommodating is at the other extreme, the “we’ll do it your way” corner. If you are an accommodator by habit, it may be because you recognize a battle that can’t be won when you see it, and consciously decide not to fight. From your perspective, this approach is quick and easy, and others are happy that they get their way. Of course, this presumes that you consciously choose to accommodate, which isn’t always the case: sometimes you’re forced to cave in and aren’t happy about it.

This distinction may not be visible, which can result in the main hazard for accommodators: resentment. The question, “Are you really okay with never having things your way?” may eat away at them, sometimes resulting in them exploding in anger later. This can be a big surprise for the other parties, who might respond with “But you always seemed to be okay with me taking charge.” I’ve heard of many divorces that caught the Competing-style partner off guard, and musicians suddenly quitting a successful band to go solo. This points to another disadvantage to the Accommodation style beside for resentment: their ideas never get heard, and maybe those ideas were really good.

Collaborating seems like the ideal corner, and is sometimes called the “problem solving” mode. Ideas get fully explored, people strive to find a win-win, and, if they succeed, everyone’s happy. This style, however, takes the most time and resources: be prepared for many long meetings, and perhaps the need to bring in outside facilitators or mediators. The word “strive” was deliberately chosen: it may take a lot of creativity to discover that win-win solution, and there’s no guarantee that such a solution exists. Sometimes groups expend all that time and energy and just give up. Or else they switch to another mode: compromise.

Compromise means everyone wins a little, but also loses a little. Each party is somewhat satisfied, but no one is fully satisfied. The reason people who attempt the collaborating style sometimes resort to this is because it’s easier: “how about if we just split it 50-50?”

Compromises may involve creativity, but often they are lazy. Laziness may explain why so many group decisions seem to be head-scratchingly bad; there was probably a mindless compromise somewhere in the decision-making process. Some compromises really are bad ideas: if you’re living in Boston with a committed partner and they get a job offer in San Diego, moving to Topeka (halfway between Boston and San Diego) is a terrible solution. I suspect that compromise is the reason why so many television shows and movies are uninspired: because there were too many people with too many different ideas involved, and they settled on a mediocre compromise.

If this makes it sound like I don’t believe in collaborative decision-making, or that all greatness has to be created by a Steve Jobs-style competitor, it’s not true: there can be great value in everyone listening to each other and giving up some of what they think they must have. Some analysts have noted that a big problem with American politics in the 21st century, for example, is that “compromise” has become a dirty word, implying a selling out of your values, and as a result, very little gets done in Congress.

Avoiding: if the opposite corner, collaborating, is the win-win corner, does that make avoidance the lose-lose corner? Logically speaking, perhaps so, but this doesn’t acknowledge that there are advantages to avoiding conflict. It may be the wrong time or place to engage in conflict, the battle may be unwinnable, and conflict takes an emotional toll on people.

It also raises the question: if conflict avoidance is dysfunctional, why is it the style preferred by most people most of the time? Some scholars, such as Stella Ting-Toomey, have argued that there is a cultural bias in labeling avoidance as the worst conflict strategy. Ting-Toomey has done a lot of research on the concept of face-saving (preserving the dignity of self and others, and avoiding humiliating people), and how it differs in individualistic vs. collectivistic cultures. In collectivistic cultures such as Japanese society, avoidance is a key tool in preserving face for other people, rather than just a way to avoid dealing with something unpleasant.[3]

Another point to make about avoidance is that it doesn’t always take the obvious form of pretending a problem doesn’t exist. An alternate form of avoidance is to have a brief discussion about a problem, but set it up in such a way that it’s too short to actually accomplish anything, and only serves to allow people to say “We dealt with that.” Saving a conflict topic for the last agenda item in a meeting, for example, might be a way of guaranteeing that the discussion only lasts for five minutes.

Another habit that could be called avoidance is talking about an issue with everyone except the person directly involved — e.g., complaining to co-workers about Andrew, but not saying anything to Andrew himself about it (which is what that group who wanted to evict two members was doing). In this scenario, a problem may be talked about at great length, but if the discussion doesn’t involve the right people, it’s still avoidance.

Finally, if you divide group life into the task side and the social side [see Chapter 16], you can avoid a conflict on one side by retreating into the other. If a work group can’t agree on how to do a task, for example, they can say “Let’s take a break and go out to happy hour.” If they’re having a personality clash, they could say “Let’s forget all this personal stuff and just get down to work.”

Again, these may be wise strategies in the short run, as long as you recognize that you’ll eventually need strategies to actually resolve what has to be resolved.

One other point: the chapter subtitle, “Can’t we all just get along?” — or its corollary, “It’s not worth fighting about” — can be helpful or extremely unhelpful, depending on who’s saying the words. If the issue at hand is your own concern, then telling people it’s not worth fighting about is fine; that just means you’re choosing the accommodating style. But what if someone else says this about your issue? That’s a way of defining the concern as trivial, which is likely to be perceived as insulting and will probably escalate the conflict. So if you’re a third party or bystander and want to say those phrases to help out, first consider how they will be perceived by the different parties.

One of the main reasons people avoid conflict is because of the emotional toll of “rolling in the mud” and hashing things out. Picturing how ugly things might get is normal, and gets people in an economic frame of mind, asking “Is it worth it? Will the benefit outweigh the cost?” In some situations you might conclude that it’s not — say, if you get frustrated with a project group a week before the semester ends, and decide “One more week and I won’t have to see these people anymore.” But there are three questions to consider if you are deciding on the value of bringing things up vs. keeping quiet:

- Will it have consequences beyond this immediate time? You may not see the group after the project is done, but if the project ends up being done badly because of unresolved issues, it will affect your grade. As a teacher, I have often heard from students who waited until after the semester was over to tell me they thought their group was doing a poor job, but didn’t say anything to the group. Likewise, I’ve read comments by movie producers and directors who seemed aware that they were producing a “stinker” but let it go, perhaps resulting in huge losses. (See the discussion of “The Adventures of Pluto Nash” and other business disasters in Chapter 5). The decision to keep your mouth shut may be a rational one — or may be an example of flawed thinking. Speaking of which…

- Is the emotional cost already too high for you? Students sometimes tell me they dread group meetings due to unresolved issues, describing the anxiety symptoms and physical effects they suffer when they think about walking into the group meeting, but then add, “But it’s not worth dealing with it because talking about it would be even worse.” Perhaps, or perhaps they could be making a poor economic decision: putting up with weeks of misery to avoid an hour of uncomfortable discussion. A child with a splinter in their finger might beg an adult not to pull the splinter out because it will hurt, not acknowledging that it already hurts, and a quick pinch will relieve the pain for good.

- Are you missing an opportunity to learn and grow? Dealing with a situation head on can help you develop your skills at conflict resolution; not doing so may deny you an opportunity to learn valuable life lessons.

————————————————————————————————–

EXERCISE: CONFLICT ANIMALS

This exercise works best with larger numbers of students; 15 may work well, 25 definitely would. It is also one that does not require a lot of explaining up front — in fact, that may hinder the process. I put the discussion questions up on slides so that students can keep referring back to them.

- Question 1: “When you are in conflict situations, what is your preferred, instinctive conflict style? (as opposed to what you have been trained or required to do). Are you a lion, a puppy, an owl, or a turtle? Based on your preferred style, go to one corner of the room to meet others who share your style.”

(Let students know which corner the lions should meet in, where the puppies should go, etc. Also let them know that they are allowed to change corners if the discussion makes them feel that they are in the wrong corner).

- Question 2 (in groups): What made you choose that animal? What are the qualities you share with that animal in conflict situations?

(For example, if they chose “turtle,” is that because of slowness, or because of having a “shell”? Encourage them to think metaphorically).

- Question 3: What are advantages and disadvantages of that conflict style?

- Question 4: What messages do you want to send to the other groups? (For example, “When you’re in a conflict with an owl, make sure your arguments are logical” or “If you get frustrated with a turtle, it doesn’t help to just yell at them to come out of their shell”)

After 20 minutes, have a representative from each group share the key points from their discussion. The teacher can then wrap things up with an appreciation of difference: although each of the animals may get frustrated with the others, all can appreciate that if everyone in the world was their type of animal, things would not go well.

- Drawing on earlier models by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton, and by Jay Hall, with “concern for task/goals” and “concern for people/relationships” as the dimensions ↵

- Kramer, M.W., & Bisel, R.S. (2021). Organization communication: A lifespan approach (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, p. 271. ↵

- Stella Ting-Toomey, “Managing Identity Issues in Intercultural Conflict Communication: Developing a Multicultural Identity Attunement Lens,” in The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity, Verónica Benet-Martínez and Ying-yi Hong (eds.), Oxford University Press, New York, 2014, pp. 485-506 ↵