Chapter 3: Ethics

3.1 Is It Okay to Say That?

As movie themes go, you just can’t beat the one from Spiderman: “With great power comes great responsibility.” Even those of us who can’t shoot spiderwebs out of our wrists can recognize the truth in it, and see the connection between power and the ethical responsibility to use that power well. Since this is a book about communication, it raises the question: does communication count as “great power”?

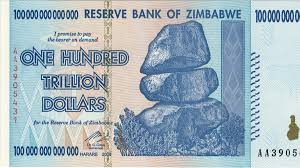

Consider this: some forms of great power are clearly social in nature, but others don’t appear to be. In the non-social category, “great power” may evoke images of vast armies, unlimited wealth, the ability to maintain a position of leadership for decades, the authority to throw rivals in prison and the liberty to kill anyone in your way without fear of punishment, and a large company’s ability to act as it pleases. But all of these powers actually depend on communication. A vast army can turn on you, and is only a form of power if you can command that army, which depends on the ability to communicate authority and inspire loyalty in your followers. As for unlimited wealth, how does “one hundred trillion dollars” sound? That was an actual unit of currency in Zimbabwe in 2009 during their hyperinflation crisis … but it was only worth roughly $30 in American currency.

Money is a social construct, which means it is only real if others agree that it is real, so it too depends on communication. As for staying in political power for decades, modern rulers who have done that (such as Vladimir Putin in Russia) know that the perception of power is vital, the control of news media is an essential component, and you’ll probably still need to keep winning elections. The authority to kill or imprison rivals is just that: authority, which must be upheld through communication. And massive corporations that can seemingly do whatever they want still pour huge amounts of money into advertising, PR campaigns, and keeping healthy relationships with governments.

In short: there is no such thing as power without communication.

To those of us who don’t command armies or corporations, it is even more obvious that our power comes from our ability to communicate. How do you get a well-paying job? How do you lead a team? How do you gain Instagram followers? How do you talk a professor into giving you an extension on a term paper? How do you haggle over the price of a car? How do you sweet-talk that attractive person into going on a date with you? Those are all forms of exercising power, so if Peter Parker’s uncle is right, they all carry a sense of moral responsibility with them as well.

This moral responsibility can be abused, not just by dictators and business moguls, but by all of us. The personal goals listed in the previous paragraph (getting a job, gaining social media followers, convincing someone to go on a date) could be achieved by immoral means: faking a resume, manipulating followers, seduction. Dramatic historical examples of immoral communication are easy to find: cult leader Jim Jones, for instance, convinced over 900 people to drink cyanide-laced juice that they knew was poisoned (from which we got the expression “drink the Kool-Aid” to refer to “accepting a deadly, deranged, or foolish ideology or concept based only upon the overpowering coaxing of another”). Bernie Madoff bilked investors out of $170 billion dollars in a decades-long Ponzi scheme, but his widely publicized arrest in 2008 didn’t seem to slow down the use of such schemes. Most scams, however, are carried out not by highly organized and motivated masterminds, but by petty criminals who discover how easy it is to make a wealthy widow fall in love with them, or get a desperate cancer patient to buy a bottle of snake oil (a generic term for medicines that do nothing). If you include things like putting a little “spin” on your resume, lying to a friend about why you didn’t come to their party, or forwarding a tweet without verifying if it’s true, most of us have misused the power of communication.

If you look closely at the ills facing modern society — war, racism, health, climate change, financial crises, politics, sexual abuse — you will always find unethical communication hiding under those rocks. Someone somewhere is lying about something, covering something up, distorting evidence, manipulating people, making promises they can’t keep, or unfairly attacking someone’s credibility. I would go so far as to say that when people are absolutely determined to fight for a cause, even one they believe is morally right, truth is the first casualty of that war. If you believe that your political candidate must win, for the good of the country or state, a little deceit and “dirty fighting” seems like a small price to pay. Often ignored in that equation, however, is the greater cost to society: the erosion of faith in institutions, government, news media, advertising, or any of the forms of communication we all depend on.